Marsh, Billings and Rockefeller Inspire a National Conservation Movement

Deforestation, barren hillsides, erosion, flooding. That was Vermont in the years before the Civil War. Americans had poured into the state after the American revolution, cutting down the forests to make pasture land, fuel, shelter—and later, a profitable industry in milled timber. The barren hills could not absorb the rain that fell. It washed soil from the hills, filling rivers with silt and threatening the native fish. When the rain was heavy, flooding occurred. Three men—successive owners of a Vermont farm—addressed the state’s problem with soil erosion, igniting a national conservation movement.

George Marsh and Frederick Billings Inspire a Conservation Movement

One Vermonter, George Marsh (1801–1882), growing up in Woodstock, Vermont, observed the deforestation there with dismay. Later, serving as a diplomat in Turkey and Italy, he drew a connection between soil exhaustion in the Mediterranean and the practices that led to erosion in Vermont. In 1861, he published Man and Nature, an early statement of what would later be called “environmentalism.”

Marsh’s home and farm in Woodstock, Vermont was bought in 1869 by Frederick Billings (1823–1890). A Vermonter who had traveled to California when gold was discovered there, he had become wealthy as a San Francisco attorney—later increasing his wealth as a railroad financier. Billings shared Marsh’s interest in land restoration. Returning to Vermont, he married and settled with his family on the Marsh estate. He decided to make it a model farm, to show that proper agricultural practices could enhance the land, rather than deplete it. He also started planting trees to reforest Vermont. Billing’s advocacy of “scientific forest management” helped ensure that Vermont’s nickname, the Green Mountain State, would be an accurate description rather than a distant memory.

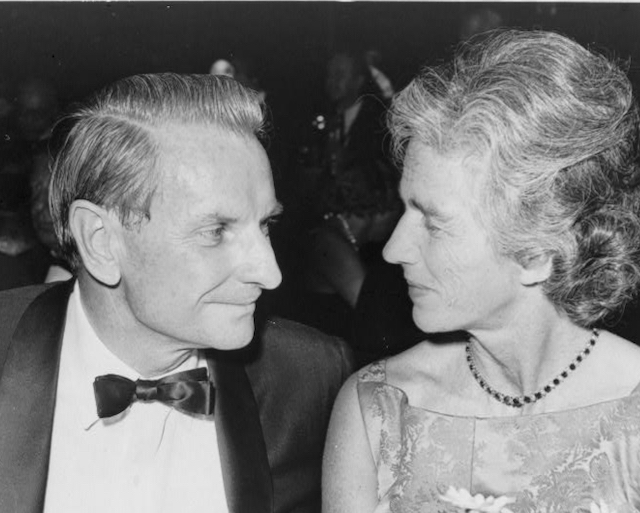

Laurance and Mary Rockefeller Promote Land Conservation

In 1934, one of Billings’ descendants, Mary French, married Laurance Rockefeller, whose own family over time used their vast fortune to create or enhance 20 national parks. A highly successful entrepreneur and investor, Laurance partnered with Mary in carrying forward their families’ pursuit of land conservation. The couple donated tens of millions of dollars to park and conservation projects throughout the country, helping preserve California Redwoods, donating his own and his father’s land to create the Grand Teton National Park, and influencing the development of national parks in Hawaii and the Virgin Islands. Rockefeller often structured their donations to attract matching grants, thus building broader support for their conservation projects.

Laurance served as an environmental advisor to five consecutive presidents, beginning with Eisenhower. Appointed by Eisenhower to chair the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), he supervised a comprehensive survey of Americans’ access to natural lands, recommending an integrated approach to conservation and public recreation. This helped to build wide public support for conservation efforts.

Laurance and Mary Rockefeller made the Marsh-Billings estate in Woodstock, Vermont their summer home, adding adjacent properties and developing recreational carriage trails through its forests. Eventually they donated the Victorian mansion and 555 surrounding acres to the National Park Service.

This story of three families and their work to build a national conservation movement is told at the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park, in Woodstock, Vermont. Although tiny in comparison to the vast national parks in the west, the park in Woodstock honors and exemplifies the conservation movement built by visionaries like Marsh and Billings. As the American frontier yielded to settlement and development, these men recognized their fellow citizens’ continued need for wild spaces. Over time they persuaded Americans that natural beauty was a useful resource, deserving of consideration alongside the utility of lumber and minerals extracted from the land.

Vermont’s Response to 21st Century Flooding

We visited the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller Park two weeks after heavy summer storms caused flooding in various Vermont communities. Many roads and bridges were damaged and broken, and many farms had been inundated. The Billings farm across the road from the national park lost its hay crop, for example. Forest restoration and the other environmentally friendly behaviors for which Vermonters are now known cannot insulate them from worldwide climate change and related weather emergencies.

Yet everywhere we went, we saw Vermonters using excavators and backhoes to repair the damage, as well as signs for food pantries helping flood-affected families. Watching a film about Marsh, Billings, and Rockefeller at the historical park‘s visitor center, we also learned that this year’s flooding fell far short of that experienced by Vermonters in the 19th century. One flood along the Saxton’s and Williams Rivers in 1826, for example, carried off seven bridges, a paper mill, a gristmill, and a dye-house (“Historical Floods in New England,” US Department of the Interior Geological Survey, 1964). Today, Vermonters recognize the need to protect their land, while continuing to support each other as they always have when weather fluctuations wreak havoc.