Multi-Day Seminar Examines the Failure of Reconstruction and Rise of Jim Crow in the South

At a recent TAH multiday seminar on “The Failure of Reconstruction and the Rise of Jim Crow,” teachers from around the country gathered in Atlanta to discuss what happened in the South during the critical decades following the defeat of the Confederacy. The war put an end to southern aspirations to create a separate, slaveholding nation. But it thrust the dominant white class and the African Americans they had enslaved into a wary, tense counterpoise. In the judgment of the seminar facilitator, Professor Brent Aucoin of the College at Southeastern, what happened after the war is “the most important part” of the troubled story of race relations in the South—and in the nation as a whole.

Aucoin opened the seminar by asking participants whether the curricular expectations in their own school districts prioritized study of what happened in the South following its defeat. Most said that, until quite recently, there was no such expectation. This confirmed what Professor Aucoin had witnessed among the undergraduates he teaches at the College of Southeastern. “Even the brightest and most knowledgeable usually bring to my classes a superficial understanding of what happened during Reconstruction. It’s probably the weakest area of their knowledge of US history.”

Why Reconstruction is Not Well Taught

In part, this is a consequence of curricular scheduling, explained one seminar participant, 2015 MAHG graduate Amber McMunn. In her own state of Texas, as in many others, students take US History I—covering European discovery and settlement through Reconstruction—in middle school. In the rushed final unit before summer begins, “they learn about the postwar Reconstruction amendments”—but do not learn why the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution did not result in immediate protection for individual African Americans’ rights. Three or four years later, students take up US History II, beginning in 1878, the year Reconstruction ended. Their teachers chart a rapid course through the transformation of America into an industrialized and imperial power, covering the emerging tensions between business owners and labor, native-born Americans and immigrants, isolationists and international activists. “That’s how Reconstruction gets glossed over,” McMunn said. Most students do not revisit the unsettled racial conflict in the South until they study the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Other factors reinforce curricular neglect of the failure of Reconstruction, said 2017 MAHG graduate Anne Hester, who traveled from Florida to attend the seminar. “Teachers today are leery of talking about certain subjects, particularly race. We don’t want to offend. We don’t want to be labeled as either insensitive or oversensitive to racial issues.” Understandable as these worries are, Hester is able to dismiss them. “I tell students on day one of my class: We are going to talk about things in this class that will make you uncomfortable and that will make you angry. . . . If you are easily offended, go see your guidance counselor now, because you are in the wrong class.” McMunn makes a very similar speech: “If you’re not comfortable in this class, then we’re teaching you the right history,” she says.

Both Hester and McMunn teach in Title I schools with diverse student bodies. Students at East Lee County High School, where Hester teaches, are 61% Latino and 21% African American. At Humble High School in Houston, where McMunn teaches, students are about 55% Hispanic and 40% African American. In both schools, students react to difficult history with dismay—but also curiosity. History helps them make sense of their own life experiences. Hester and McMunn attended the seminar to find answers to their students’ questions.

What Teachers Were Surprised to Learn

The reading packet, spanning the years between 1865 and 1896, covered debates at both the state and federal level on the civil rights of freedmen, along with Congressional legislation, constitutional amendments, and Supreme Court interpretations. Aucoin observed that, like most of the undergraduates he teaches, some of the seminar participants were surprised by the extent of the efforts undertaken by the federal government to ensure the civil rights of African Americans in the postwar period. “Reading the Civil Rights Act of 1875, some teachers were surprised to learn that for a time after the Civil War, segregation was illegal. If you’ve read C. Vann Woodward’s Strange Career of Jim Crow, you take this for granted. You understand that in the first post-war decade, Congress made a great, revolutionary effort to establish equality. You understand that in the following decades a counter-revolution led by white Southerners, and aided and abetted by the Supreme Court and the federal government itself, completely undermined the gains made.”

Aucoin wanted teachers to see the complex factors rendering the Reconstruction amendments ineffectual to protect Freedmen’s rights. “The Fourteenth Amendment was written in response to the Black Codes” passed by southern state legislatures soon after their readmission to the union. “It was written to focus on state action—to say that no state shall deprive a person of equal protection and due process under the laws. At the time, the states were the culprits in denying African Americans their civil rights. I don’t think many of those in the seminar had made that connection before.”

Even before passage of the Reconstruction amendments, “long cherished concepts of democracy and federalism” were invoked to obstruct guarantees of freedmen’s equal rights. “Like the students I teach at Southeastern, teachers in the seminar were somewhat surprised by the complexity of the argument that arose. In a sense, it was a conflict between differing American ideals.” In the Declaration, Americans had affirmed the equality of all human beings. Yet the constitution was written to give individual states a large measure of autonomy over such matters as procedures for voting and maintaining civil order. “We read an argument for granting amnesty to ex-Confederate leaders—for restoring to them the rights to vote and hold elective office. We saw that this argument was based on the American respect for democracy, and that opposing it almost made you un-American. The same argument occurred over federalism: that continuing to subject the ex-Confederate states to federal rule and authority amounted to nationalism, to abandoning the federalism of our founding fathers. It seemed as though Congressmen had to choose between dueling ideals which previously had not been seen as conflicting.”

Rhetorical Appeals to Custom; Logical Appeals to Justice

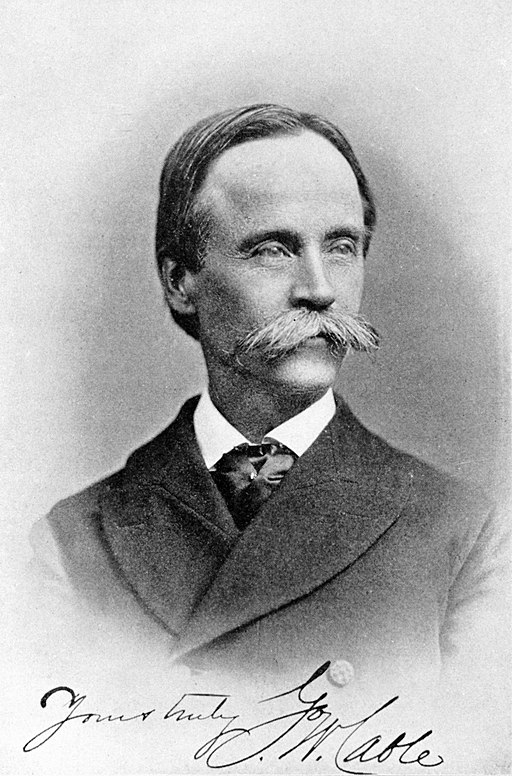

Teachers also discussed the engrained cultural attitudes that, after Reconstruction, supported the institution of the Jim Crow system. McMunn was struck by two essays written by white southerners in 1885. Two years earlier, the Supreme Court had effectively permitted racially segregated public accommodations in its ruling on the Civil Rights Cases. It found that the Fourteenth Amendment did not permit the federal government to outlaw racial discrimination in hotels, theaters, or transportation facilities that were privately owned. Neither essay questioned the constitutional soundness of the Court’s ruling. However, one writer—George Washington Cable, who as the son of a slave owner had himself fought for the Confederates—castigated his own region for using segregation and other practices to keep freedmen in a servile position. Henry Grady, the influential editor of the Atlanta Constitution, defended the practices Cable condemned.

“Cable writes as if, ‘I’ve seen the light,’ arguing that white and black people can live and work together in a just relationship. Grady argues that neither race really wants to mix together—that integration would make people uncomfortable,” McMunn summarized. She had been surprised by Grady’s ability to make his argument sound plausible. Aucoin commented, “Grady’s writing style is excellent.” More effectively than Cable, he engages the sentiments of his audience; “but his argument is very much lacking,” as teachers discovered when they examined the two essays side by side.

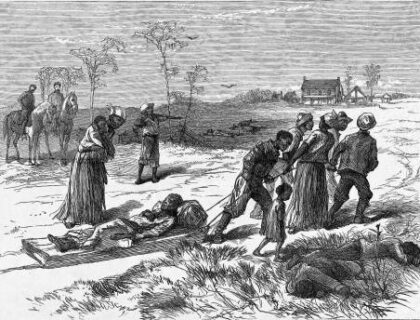

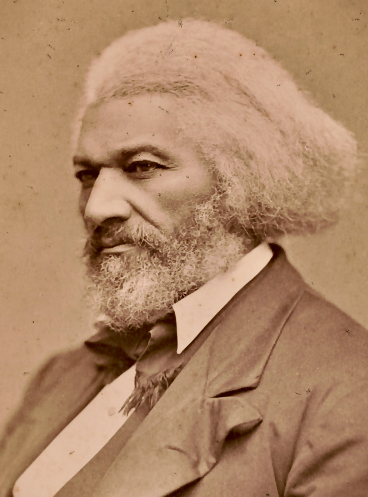

An essay written two years before Cable’s and Grady’s, Frederick Douglass’s “The United States Cannot Remain Half-Slave and Half-Free,” struck McMunn as the most powerful of the readings. Douglass wrote before the ruling in the Civil Rights Cases, but after the Court’s ruling in Cruikshank effectively shielded those who led the Louisiana Colfax Massacre from prosecution. Invoking Lincoln’s prewar “House Divided Speech” in his speech’s title, Douglass warned that the federal government’s abandonment of Reconstruction was relegating many of the emancipated to a status very much like slavery. McMunn found Douglass’s impassioned protest, combined with his hope for justice, moving and poignant.

Aucoin agreed. “That speech really hit home with the teachers, because of the beauty of its rhetoric and the power of its logic. It dispels Grady’s insinuations that blacks were incapable of intelligent self-rule. Here you have the eloquence of an ex-slave surpassing that of the preeminent man of letters in the South.”

Frequently during the seminar, teachers called attention to the prophetic import of the documents. Writers like Douglass, Cable, Thaddeus Stevens, and Justice Harlan (writing the dissent in Plessy) pointed out that “as long as African Americans are denied full equality, our race problem is just not going to go away,” Professor Aucoin said. “As long as there’s an aggrieved group, they will continue to press for their equal rights, and others, seeing the injustice, will continue to advocate on their behalf. Conflict and tension will continue until equality and justice are achieved. For the teachers, these arguments foreshadowed that of Martin Luther King, Jr., when he said that the moral arc of the universe always bends towards justice.”

What Teachers Carried Back to Students

After the seminar, teachers spoke of what they’d learned. McMunn, who teaches a two-year International Baccalaureate (IB) course on the History of the Americas, plans to add historical background to the 9-week unit she devotes to the Civil Rights movement. “Now I’m going to revamp what I teach at the beginning of that quarter, so students will understand how and why Reconstruction failed and how Supreme Court decisions undermined protections for African Americans.”

Hester teaches a course similar to IB, the US History component of Cambridge Assessment International Curriculum Education (AICE). It is a collegiate level course with a nationally normed final exam. Like IB, it takes a deep dive into a particular window of history. Fortunately, that window—1820 to 1940—places the Reconstruction era in the center. Hester also teaches an Honors US history course that, following the Florida curricular standards, begins in 1850 and concludes in the present day. “We start off with what threatened the deconstruction of the United States,” Hester said. “And then we jump right into the reconstruction of the United States.”

For Hester, the opportunity to talk among fellow teachers about the failure of Reconstruction was as important as the resources the seminar provided. “Reconstruction is such a touchy subject. But we need to understand this history so we can prevent it in the future. Professor Aucoin led a discussion in which we said, ‘This is how I understand it; how do you understand it?’ He would say, ‘I think what you’re saying is this. Can you elaborate on that?’ As in all TAH seminars, we were given a model through which we can host civil discourse in our own classrooms.”