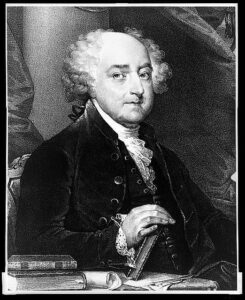

Federalist 51: Madison's Unique Contribution to the History of Political Thought

In Federalist 51, Publius (James Madison) argues that the separation of powers described in the Constitution will not survive “in practice” unless the structure of government is so contrived that the human beings who occupy each branch of the government have the “constitutional means and personal motives” to resist “encroachments” from the other branches. This argument made the essay famous, but it is another argument appended to it that Madison believes places the American system in “a very interesting point of view.” To what point of view is our gaze thus directed with this unusual (for Madison) expression of enthusiasm?

The main argument of Federalist 51 is that the various powers of government must be exercised separately and distinctly in order to “guard the society against the oppression of its rulers”. But even if society is thus protected from its “rulers”, one part of society might still suffer injustice at the hands of another part of society. The most important example is a majority, “united by a common interest”, that renders insecure the rights of a minority. Federalist 10 taught us that the republican solution to this problem is to extend the sphere, that is, by means of a federal system to create a country so large in area and in the number and diversity of citizens and interests that it will be difficult for an interested majority to form. The less famous part of Federalist 51 develops this line of thought.

Madison’s argument begins with two premises. The first, as we also know from Federalist 10, is that a majority will almost inevitably act like a faction and oppress the minority. The second is that “justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be, pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” To explain the political result to which these two premises lead, Madison describes what happens in a state of nature. There, stronger people oppress weaker people, but the former are not so strong that they are unaffected by the attempts of the weaker people to obtain justice, to protect themselves. In fact, in the state of nature, where there is no government, the “anarchy” is so great that even the stronger people “are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak, as well as themselves.”

Madison then argues that something analogous occurs within every society. When a majority oppresses a minority, which it will almost always do where there is freedom, and then when a minority pursues justice, which it also will always do where there is freedom, anarchy and uncertainty are the result. Indeed, they become so great that everyone, even the majority whose misrule caused the problem in the first place, will be “gradually induced” to wish for a government that can protect all parties.

This seems like a good thing until we learn what such protection entails. For stability and security have been established historically only “by creating a will in the community independent of the majority, that is, of the society itself.” In a small society, the majority “soon” calls for “some power altogether independent of the people”. The requisite will or power must be independent of the majority, otherwise it could not restrain the majority. This method of solving the problem, Madison adds, “prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self-appointed authority”, which are the two main ways of being independent of the people. In other words, rule by an hereditary king or by a Caesar or a general who seizes power in a coup are attempts to deal with a fundamental political problem, which is perhaps why Madison avoids here such odious terms as “tyrant.” In any case, the idea is that even in republics, indeed, especially in republics where freedom permits interested majorities to form, citizens eventually come, for the sake of stability and security, to wish or to call for monarchy or a “self-appointed” strong man.

This fact implies that republican government is doomed to fail. Fortunately, however, for the “sincere and considerate friends of republican government,” there is another method of dealing with the problem: a properly constructed federal system. For on such a system we can create a country so large and disparate that factious majorities – majorities formed on any other principles than “those of justice and the general good” – become “very improbable, if not impracticable”. In this case, Madison explains, there will be less “pretext … to provide for the security of the [minority], by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the [majority]: or, in other words, a will independent of the society itself.”

Thus, only a large republic can escape the political logic that leads from factional conflict to either authoritarian or hereditary rule. Stated positively, only a large republic makes possible self-government, or government wholly dependent on the will of the society with no participation at all of “a will independent of the society itself”. Majorities in an extended republic will not always be just, but they will less often be unjust, and so minorities are much more likely to feel secure. The result is a more stable society as well as a more respectable one, for only in this system will the majority, which Madison here identifies with the people and even with the “society itself”, deserve our respect as being (more often than not) a voice for “justice and the general good.”

Federalist 51 thus places American federalism in a “very interesting point of view” in three respects. First, it reveals what self-government means: not that each individual governs himself or herself, but rather that no entity that is “independent” of the society itself participates at any level in the government of society. Unlike in Great Britain, where an hereditary monarchy and a House of Lords, both of which are independent of the people, share in governing, in America, every part of the government depends directly or indirectly on the people. Secondly, while republican government is not unique to America, the argument indicates that only in a federal system like that found in America does republican government have a reasonable chance of maintaining itself. Indeed, Federalist 51 suggests that the federal system is as essential as the separation of powers for the success of free government. Thirdly, to his concluding statement of the idea that the larger the society, the more capable it will be of self-government, Madison adds the remark, “notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained.” Among those contrary opinions is above all that of Aristotle, who argued that good government was possible only in a small polity. In this view, the teaching on federalism may be the Federalist Papers’ most important contribution to the history of political thought.