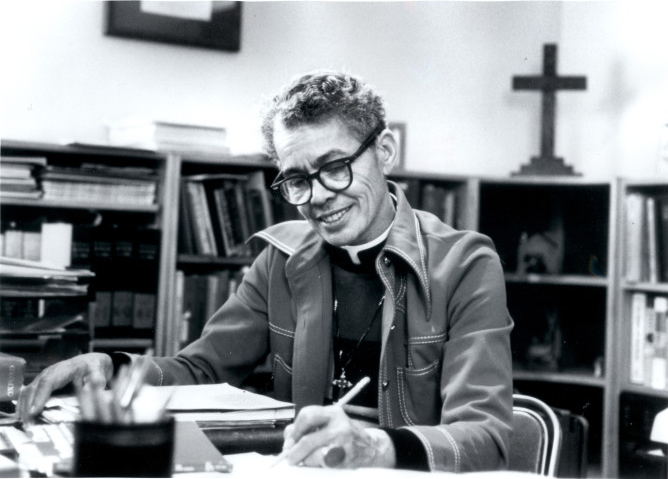

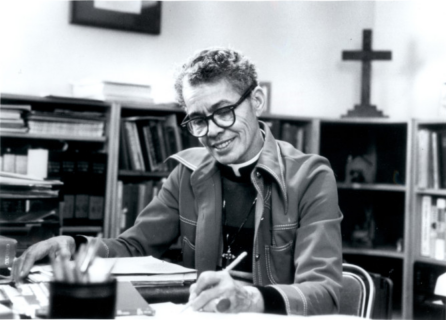

Pauli Murray and Brown v. Board of Education

Today, on the anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, we remember Pauli Murray, who suggested the strategy Thurgood Marshall used in that case.

Murray was the granddaughter of a Black Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who came to North Carolina after the war to start a school for freedmen. Although poor, her family were respected leaders in the African American community around Durham, NC. Her aunts, who taught school, helped Murray secure a scholarship to attend Hunter College in New York City. Graduating during the Depression, she worked for the Works Progress Administration in its Workers Education Project before enrolling in Howard University Law School, from which she would be the first woman to graduate.

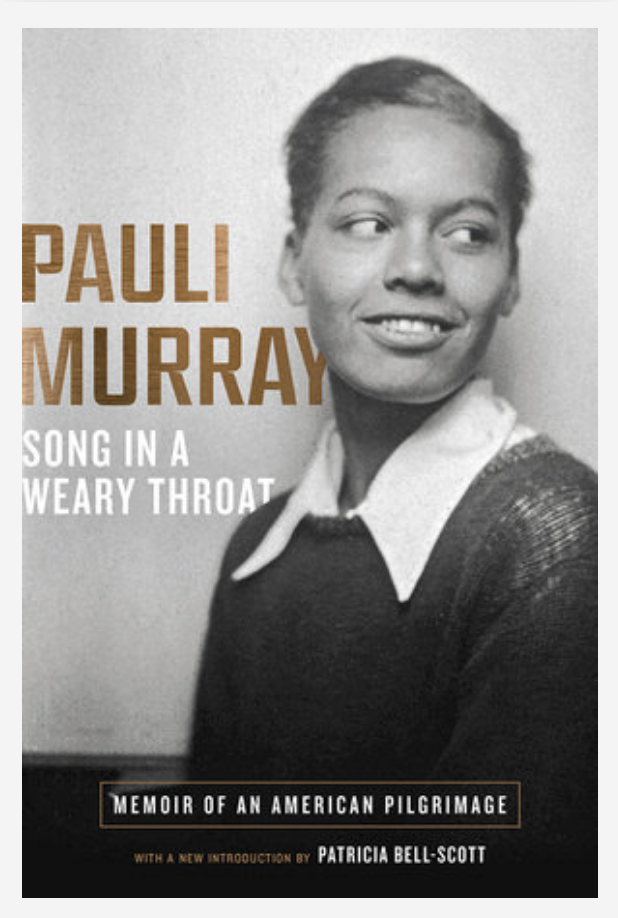

In 1944, while taking a senior law school seminar on civil rights, she “advanced a radical approach that few legal scholars considered viable” at the time. As Murray recounts in her autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat (Norton, 1987), the NAACP had been “continuing to acquiesce in the Plessy doctrine while nibbling away at its underpinnings on a case-by-case basis.” In each challenge to segregated educational facilities, it had to demonstrate “that the facility in question was in fact unequal” (p. 285-286).

Murray Challenges Segregation on Her Own Behalf

Murray was well aware of this history, having earlier applied for admission to the law school at the University of North Carolina (Murray was actually a descendant on her mother’s side of the white family who gave the state the land on which the university was built). Ironically, she’d sent in her application shortly before the 1938 Supreme Court decision in Gaines v. Missouri, which had found that because the Negro university in Missouri lacked a law school, there was no “equal” educational facility for Lloyd Gaines, a Black law school applicant, to attend.

Learning of the Supreme Court decision ordering Lloyd Gaines’ admission to the University of Missouri law school, she hoped her admission to UNC would follow without fanfare. Instead, news of her application was leaked to the press, and the university president, Franklin Graham, became engulfed in a public controversy over the pace at which desegregation of North Carolina’s public universities should proceed. Graham told Murray her application would have to wait until the NC legislature came up with a desegregation plan.

A Frontal Assault on the Constitutionality of Segregation

Now a top student at Howard, Murray suggested to her professor, Spotswood Robinson, that it was time “to make a frontal assault on the constitutionality of segregation per se.” In her autobiography, Murray recalled the reaction of her male classmates: “First astonishment, then hoots of derisive laughter, greeted what seemed to me an obvious solution. My approach was considered . . . likely to precipitate an unfavorable decision of the Supreme Court, thus strengthening rather than destroying the force of the Plessy case” (p. 286).

Robinson “not only poohpoohed my idea but good-naturedly accepted my wager of ten dollars that Plessy would be overruled within twenty-five years.” Murray, admitting that “opposition to an idea I cared deeply about always aroused my latent mule-headedness,” decided to argue her proposal in her semester paper for the course. Her mentor at the law school, Leon A. Ranson (who had probably pulled strings to gain admittance as well as a tuition scholarship for the lone female student), “egged me on and even extended the deadline for my paper” (p. 286).

Murray’s Civil Rights Activism

That was fortunate, since Murray, who had since her undergraduate days participated in civil rights efforts, soon was drawn into leadership of a student effort at Howard. They organized one of the first sit-ins, at a downtown Washington, DC restaurant. This little-known effort—occurring sixteen years before the sit-in at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, NC—seemed about to succeed in persuading a restaurant owner to permanently open his business to all customers, black and white. However, officials at Howard, worried that the effort might jeopardize the school’s federal funding, called a halt to it. Murray’s activism took a toll on her academic performance. Although she had posted top grades during her first year of law school, she graduated only cum laude.

Murray wanted to teach law, so she applied for a fellowship to do a year of graduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley, Law School (after first applying to Harvard Law School, where she was denied admission on account of her sex). One year of post-graduate study was not enough to secure a faculty position, especially for an African American woman. She opened her own law practice in New York City, then carried out an extensive study of segregation laws across the nation at the request of the Women’s Division of the United Methodist Church. Asked to prepare a pamphlet, she produced a 746-page tome. The ACLU funded its distribution to state law libraries, human rights agencies, and law schools around the country. Thurgood Marshall gave each member of the legal defense team of the NAACP a copy and they consulted it regularly during their work on desegregation of schools and other facilities.

Later, Murray taught law in Ghana (where she unsettled the Nkrumah government by teaching courses emphasizing human rights), earned a doctorate in law at Yale, and became a professor of American Studies at Brandeis.

Murray’s Influence on Brown

Still, when the Brown decision was announced, “not twenty-five but only ten years” after Murray made her bet with Professor Robinson, Murray didn’t realize her paper suggesting a direct attack on the “separate but equal” doctrine had influenced Thurgood Marshall’s strategy. She learned this only in 1963 while visiting her former law professor, Spotswood Robinson, who gave her the $10 she had bet him nineteen years before. When she asked him what became of the paper she wrote for his senior seminar, he pulled it from his file cabinet and had a copy made for her. Then,

. . . he casually mentioned that when he had left the law school to go into private practice, he had taken my paper with him. He had not thought much of it when he first read it . . . but in 1953, when the NAACP legal defense team was preparing arguments for Brown v. Board of Education, he took another look at it and thought better. ‘In fact,’ he went on, ‘it was helpful to us. We were able to use your paper in the Brown briefs . . . .’ Thinking of all the years that had passed without my knowing that my work had not been wasted effort, all I could say was, ‘Spots, why on earth didn’t you tell me?’

Song in a Weary Throat, (Norton, 1987), p. 229-230.

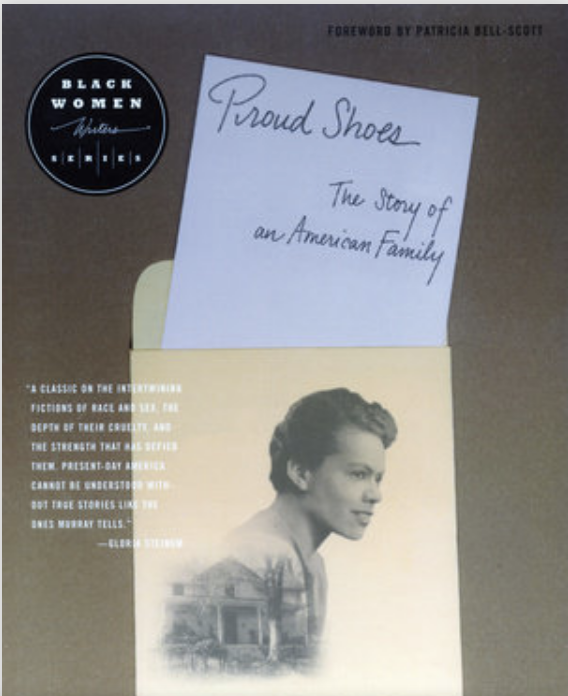

Robinson’s off-hand acknowledgment of Murray’s contribution was in keeping with much of her experience during her career. Often ahead of her time, she did critical work that paved the way for later civil rights successes. While in her twenties, she made a lifelong friend of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who often pushed President Franklin Roosevelt on civil rights causes that Murray brought to her attention. In the 1960s, Murray became an advocate for feminism, suggesting to Betty Friedan the formation of an “NAACP for women” that would become the organization NOW. A poet and writer with a deep spirituality, she ended her career by attending seminary and becoming the first African American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest.