Preserving the Common Ground of American Citizenship: Jefferson's First Inaugural, Part 2

Jefferson’s First Inaugural succeeded in its work of reconciliation, as the responses to it from key Federalist leaders show, because he found a way to assert the policies of the Republican party without unduly alarming Federalists. It succeeded for three other reasons, however, which tell us something about the prospects for preserving the common ground of American citizenship in our own time.

Appeal to Shared Principles

The first of these reasons is that Jefferson appealed to a principle or principles shared by Federalists and Republicans. Jefferson said that “every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” Interestingly, Jefferson did not say explicitly in his Address what this principle was. Nevertheless, he was right that both parties adhered to and thought they were defending the principles of ’76. This was not the case when Lincoln sought to preserve the Union 60 years later, at least as far as the principle of equality was concerned.

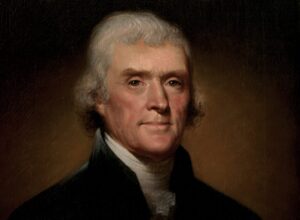

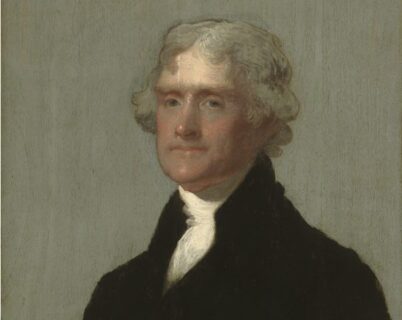

The Importance of Character

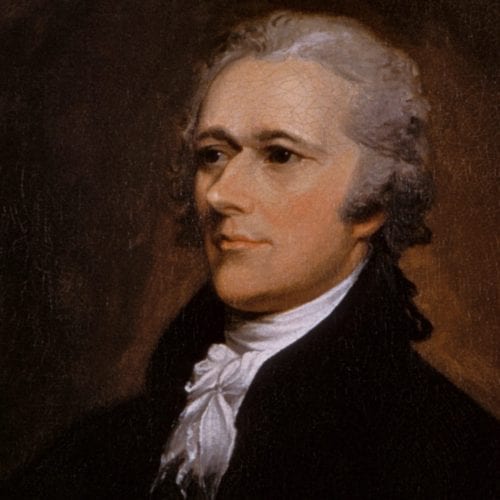

Jefferson’s carefully chosen words succeeded for a second reason: because of the character of the man who uttered them. This character had made Jefferson president, because at a critical moment Alexander Hamilton intervened to reassure his fellow Federalists that whatever they thought of Jefferson’s policies or of the man himself, he was a better choice than Aaron Burr. Federalists might not like Jefferson’s principles, argued Hamilton, but at least he had some. Burr had none. He was unfit for office. Burr was pure blind self-interested ambition and thus a mortal threat to the republic, according to Hamilton. Given what Hamilton thought of Burr, it was hardly a compliment to Jefferson that he preferred him to Burr. Still, Hamilton’s advocacy of Jefferson was a grudging but admirable act. In return, the moderately conciliatory Inaugural Address confirmed what Hamilton had said of Jefferson, and signaled to the Federalists that he was, as Hamilton implied, fit for the office he assumed.

Presidential Moderation

The third reason for the success of the Inaugural—why we remember it as more than mere rhetoric—was that Jefferson confirmed its words with his subsequent deeds. He did not have an enemies’ list; he conducted no purges. For the most part, competent Federalists remained in federal office. As Hamilton predicted, Jefferson recognized that he could not simply overthrow all that Hamilton had set up without damaging the republic, so he focused on pursuing republican policies without a wholesale restructuring of the government apparatus he inherited from the Federalists. A measure of Jefferson’s moderation was that he disappointed some Republicans, who came to oppose his policies as too “Hamiltonian,” while winning over some Federalists. Over time, the extremes in both parties were marginalized and the country entered the so-called Era of Good Feelings.

This third reason for the success of the Inaugural Address—eloquent words followed by confirming deeds—points to one of the enduring changes brought about by the election of 1800. The controversies of the 1790s over domestic and foreign policy created two parties, the Federalists and the Republicans. Jefferson was the undisputed leader of the Republicans. Although he saw his party not as a permanent feature of American political life but as an emergency measure necessary to bring the country back to its true principles, parties became indispensable, and Jefferson the first president who was both the head of state and the head of a party. Once the Era of Good Feelings ended, presidents had to balance the demands of a position that required them both to represent all the American people, especially in times of crisis or emergency, and promote the interests and purposes of a party. Not all presidents have managed this difficult task.

The dual role of president and party leader highlights a problem inherent in democracy. The presidency has great power. If the president is a popular leader and not just a head of state, what will prevent the president from ruling as a demagogue, someone like Aaron Burr, as Hamilton saw him, who would put his own interest ahead of the public’s and use the power of his office accordingly? As long as the parties were strong, they helped to protect against this danger. State and city political leaders gained national power and authority through the national parties, which relied on them. These state and local “barons” and “bosses” helped select the president and thus had control over him. We might see this as another example of Madison’s argument in Federalist 51 about ambition counteracting ambition, but, as Madison would have agreed, patriotism may accompany ambition. May it always!