Produce the Body: A History of Habeas Corpus

William Blackstone referred to it as the second Magna Carta. Chief Justice John Marshall called it the “great writ.” It has been part of Anglo-American common law since the Middle Ages. What we are talking about, of course, is habeas corpus, a Latin phrase meaning “you should have the body.” Put most simply, habeas corpus allows a person who has been detained the chance to challenge that detention in court. This, for example, prevents the government from holding an individual indefinitely without bringing charges against him or her. But this is not all habeas corpus is used for. Its primary purpose today is as a post-conviction remedy for state or federal prisoners who want to challenge the validity of federal laws that were used in securing their conviction. Habeas corpus is also used in immigration or deportation cases, matters concerning military detentions, court proceedings before military commissions, and convictions in military court. In addition, habeas corpus is used to determine preliminary matters in criminal court, such as an adequate basis for detention, removal to another federal district court, denial of bail or parole, a claim of double jeopardy, failure to provide for a speedy trial or hearing, or the legality of extradition to a foreign country.

Some scholars locate the origins of habeas corpus in Roman law, though this is a disputed point. Less controversial is the claim that habeas corpus originated in Article 39 of the Magna Carta, which held that “no Freeman shall be taken, or imprisoned…but by lawful Judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land.” Whether this is specifically referring to habeas corpus is unclear, but it seems likely that the Magna Carta had something like the writ in mind. Regardless, the writ of habeas corpus evolved in medieval English courts where a sheriff could be served with the writ. A court could then order the release of that prisoner if it was found he or she was being held without cause.

The modern understanding of the writ of habeas corpus as a protection of civil liberty came to fruition in the 17thCentury during the struggles between Parliament and the monarchy. The Petition of Right in 1628 charged that the king’s jailers were ignoring writs of habeas corpus and illegally detaining English subjects. In 1679, Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act, which applied to sheriffs and jailers who were causing delays in answering habeas writs issues by common law courts. The Act imposed strict deadlines for sheriffs and jailers to respond to the writ. It also imposed heavy fines if sheriffs or jailers did not respond to the writ quickly. The Act even went so far as to say that the writ applied to “privileged jurisdictions,” or special jurisdictions where the common law did not apply. At this point, habeas corpus had come into its own in Britain, but it now needed to make its way over to the new world.

When the United States Constitution was written, the writ of habeas corpus was the only English common law writ given specific reference in the document. Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides that “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” This provision, known as the Suspension Clause, both recognized the existence of the writ of habeas corpus and stipulated the conditions under which it could be withheld. Two years later, in the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress provided that both justices of the U.S. Supreme Court and judges of the federal district courts “have power to grant writs of habeas corpus for the purpose of inquiry into the cause of commitment.” Importantly, though, this law only applied to people in custody by the federal government or being tried in federal courts. Federal judges thus did not have the power to extend the writ to prisoners in the states.

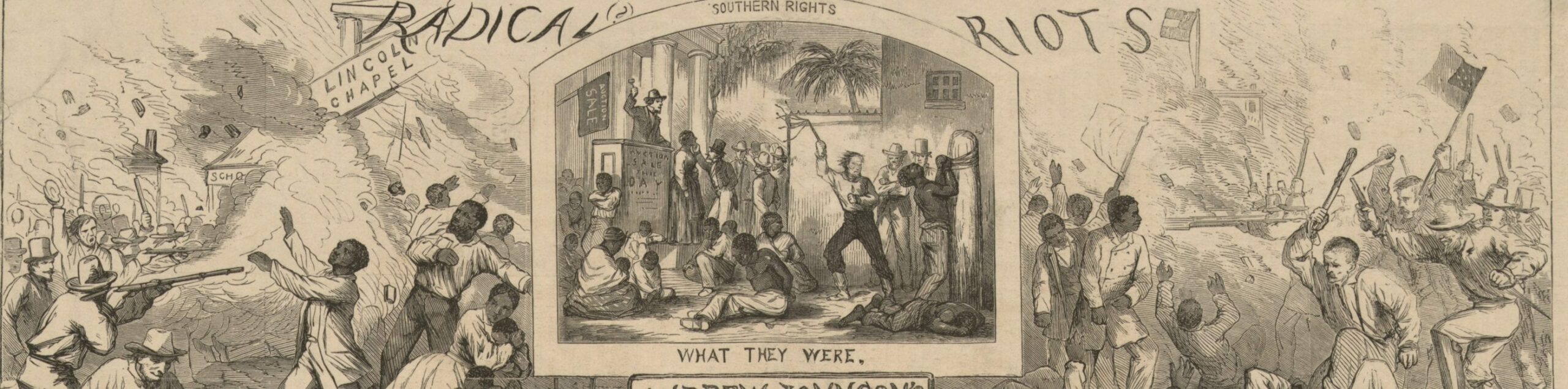

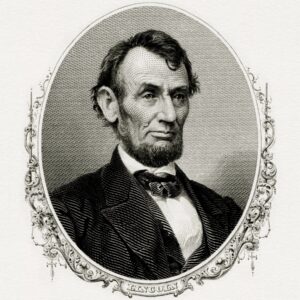

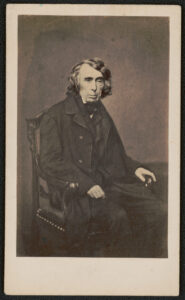

During the Civil War, the Suspension Clause was put into effect by President Lincoln at the beginning of the war to deal with saboteurs and traitors operating in the state of Maryland. Under the suspension of the writ, John Merryman was arrested by military authorities, and he was detained at Fort McHenry outside Baltimore. Merryman’s lawyers petitioned Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney (who also sat as a judge on the U.S. Circuit Court of Maryland) for a writ of habeas corpus. The issue in Ex parte Merryman was whether Lincoln, as president, could constitutionally suspend the writ in a case of rebellion. That the country was in a state of rebellion no one had any doubt. But the Constitution located the Suspension Clause in Article I, which dealt with the powers of Congress. This seemed to make it a legislative power and, therefore, one the president could not exercise alone. Lincoln believed the suspension of the writ could be undertaken by either the president or Congress, especially if Congress was not in session when an emergency broke out.

Taney disagreed and held that Lincoln had violated the Suspension Clause by suspending the writ. Yet, Taney seemed to recognize the limited scope of his power and, therefore, did not order Merryman’s release. Instead, he filed his opinion with the U.S. Circuit Court of Maryland and ordered that a copy of the opinion be delivered to the president. Taney concluded that “it will then remain for that high officer…to determine what measures he will take to cause the civil process of the United States to be respected, and enforced.” In the end, the Merryman decision became a moot point as Congress retroactively approved the suspension and passed sweeping legislation that authorized Lincoln to suspend the writ for the duration of the war. Moreover, the case left unanswered who has the actual power to suspend the writ since Taney did not write in his capacity as Chief Justice and, therefore, the case did not become Supreme Court precedent.

During Reconstruction, in tandem with the passage of the 14th Amendment, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867. This Act provided “That the several courts of the United States, and the several justices and judges of such courts, within their respective jurisdictions, in addition to the authority already conferred by law, shall have power to grant writs of habeas corpus in all cases where any person may be restrained of his or her liberty in violation of the Constitution, or of any treaty or law of the United States.” What this meant, significantly, was that federal judges could now issues writs to state prisoners in state cases for violations of their constitutional rights. This expansion of federal review of state proceedings reached a peak in the 1950s and 1960s in Brown v. Allen (1953) and Fay v. Noia (1963), which allowed a vast array of appeals from the state level. It also created a great deal of tension between the states and the national government and raised issues of federalism.

In 1996, Congress narrowed the writ of habeas corpus though passage of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). The Act had three important components. First, it imposes a one-year statute of limitations on habeas petitions. Second, unless a United States Court of Appeals gave its approval, a petitioner could not file successive habeas corpus petitions. Third, habeas relief was only available when the state court’s determination was “contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of clearly established federal law as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.” Congress attempted to narrow habeas corpus further during the War on Terror with the Detainee Treatment Act (2005) and the Military Commissions Act (2006). These acts provided that prisoners held in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba may not access the federal courts through habeas corpus but, instead, had to go through military commissions. In a number of cases, however, the Court has chipped away at these acts and, most recently, in Boumediene v. Bush (2008), expanded the territorial reach of habeas corpus saying that the Suspension Clause guaranteed the right to habeas corpus review to prisoners detained in Guantanamo. Clearly, therefore, the issues related to habeas corpus have not all been resolved, yet it remains without question one of our most important civil liberties.