Professional Development with TAH

A Master’s Degree with MAHG is Worth It!

Ready for some meaningful professional development? Registration for MAHG’s Summer 2022 semester begins on February 1st at 8:00 am Eastern. View our schedules of online and weeklong on-campus courses. Already enrolled at Ashland? Register via Self-Service. Ready to get started on your master’s degree? Apply for admission today. Interested in taking one or more courses on a non-degree basis? Review our upcoming schedules and register today.

Near the end of the second 2021 summer session of MAHG, we asked two teachers new to the summer residential program to tell us what they were experiencing. Each had taught between five and ten years and knew they’d found their life’s profession. Still, two weeks of summer courses at the Master of American History and Government (MAHG) program in Ashland, Ohio seemed a big commitment.

Amy Livingston, now teaching US history to eighth-graders at Sweetwater Junior High School in Tennessee, began teaching in Florida, where she transitioned from a classroom assistant position to teaching 7th grade US civics. Traveling to Ashland meant leaving her three elementary school-aged children for the very first time in their lives.

Tina Boudell teaches 11th grade US history and Advanced Placement US history at Doral Academy, Red Rock in Las Vegas, Nevada. She’d learned about MAHG from the social studies coordinator at Doral Academy, Karlye Mattie, who told Boudell to expect intense, exciting week-long classes. Mattie also gave Boudell a few practical tips, pointing out, for example, that the bed linen packet she’d receive contained only flat sheets. “As I packed a new twin-long fitted sheet into my suitcase, I wondered, ‘Why am I doing this? Why am I leaving my husband for two weeks?’”

By Thursday of the second week, Livingston and Boudell said the demanding program was fully worth the effort and the time away from family.

_______________

Ellen Tucker: Why do you commit to the MAHG program, especially since it requires you to take half of your credits on the campus of Ashland University?

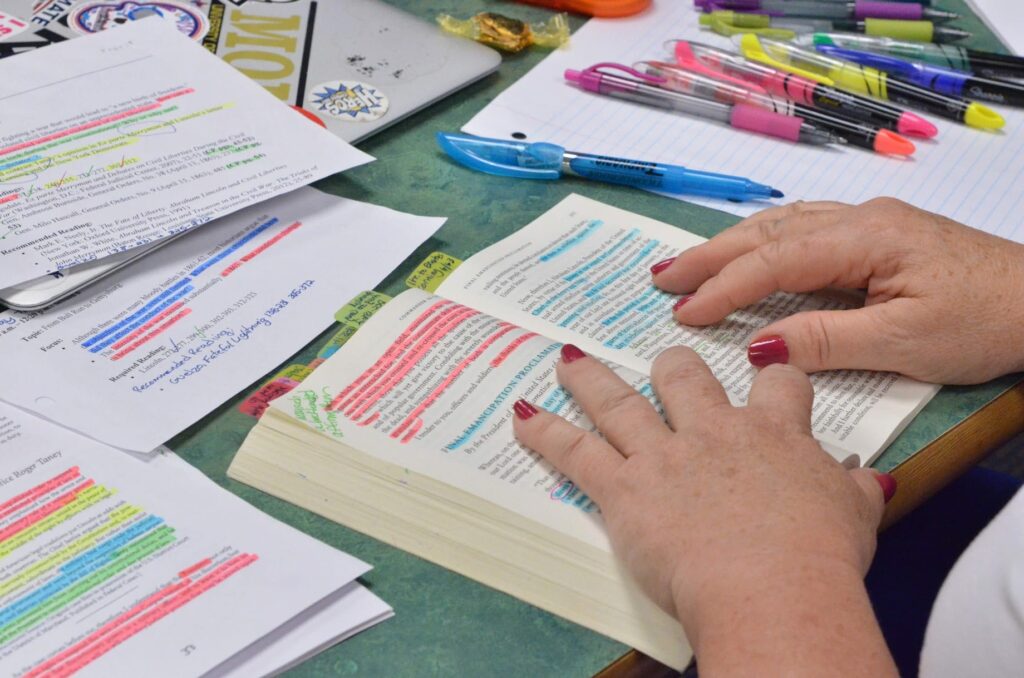

Boudell: Since starting my teaching practice, I’ve wanted to focus on primary source documents. I thought my undergraduate program taught me how to do that. Then I participated in a free TAH Saturday seminar held at my school. I saw that your entire program is primary source and discussion-focused. This program asks me to do what I want my students to be able to do, and I need to set that model for them.

Livingston: This program is just the gold standard. It helps me be the best teacher I can be. I even see that the way I teach is changing.

I’m more confident in my content area. I also look at things differently. In my Founding class, one of the essay topics was, “How does the Declaration of Independence lead to the Civil War?” My first thought was “Wait, what?”

I’m learning the story of us—the whole history comes to mean something. I want to get that across to my students. Many enter my class thinking history is just names, dates, people, and places—isolated events that have no meaning. But what happened in 1776 affected 1860 and the election of Abraham Lincoln. Getting students to draw those connections, seeing that it all does matter, has been really cool.

Tucker: Tina, have you watched students making new connections?

Boudell: I’ve experienced it. In the Founding class I’m taking this week, we read Federalist 51, in which Madison says men are not angels, and so “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” I realized, “Yes, this is how our system of checks and balances works!” When students apply this idea to the current presidency, seeing how executive power is checked in our constitutional system, it becomes personal to them. They take ownership of their learning.

Tucker: How do primary documents help students practice critical thinking?

Livingston: After students compare the arguments in two documents, they can come up with their own arguments.

Boudell: They learn not to rely on someone else’s explanation. Textbooks tell a secondhand story. If you want an overview of what happened, read a secondhand source. But if you want to know what Hamilton actually meant, you need to read his own words. I always tell my students, “You don’t want someone else telling your story for you. You want to be the author of your story. So, let’s see what the earlier Americans we’re studying actually said.”

Asking students to analyze the documents is crucial. My job is not to teach them what to think; my job is to teach them how to think. I appreciate that the professors here do the same thing. Of course, it’s intimidating at first when they ask, “What are your opinions?” I always feel, “no, that’s not my place!” But it’s really encouraging that we are not being indoctrinated in one historical view. We think critically for ourselves, and that is reflected in our teaching.

Tucker: Do your students struggle with the older language of, say, 18th century texts?

Boudell: One thousand percent!

Tucker: How do you deal with that?

Boudell: It’s brought up the rigor in my class. Even when I taught 7th grade, I used some primary sources. Early in the year, that could mean struggling over a single document for two or more days. There are times when you say, “We’re just going to read these two sentences and talk about what they mean.” But once they learn to break down the language, it gets better. They apply their new skills to all the following documents. They can also apply those skills to other content areas—science, language arts, etc.

Tucker: Do students bring to class ideas about American history that they later rethink?

Livingston: It often has a lot to do with race. The school where I teach now has a predominantly black student body. If you ask students, “What do you think?” and “Why do you think that?” discussion can be open and honest. For example, I might ask, “why didn’t those helping Jefferson finalize the language of the Declaration want him to keep the clauses accusing the British of imposing slavery on the colonies?” I do try to humanize the founders, to remind students that they were imperfect men trying to do the best they could at the time. They made some choices we wish they hadn’t. But we can try to understand the process they went through.

Tucker: What happens when students argue?

Boudell: I do a lot of team-building at the start of the year. We talk about our emotions, how we can get angry or sad. We build on that to develop a circle of trust. We have an agreement that whatever is said in the classroom will not affect my view of you. After all, the founders disagreed—there were federalists and antifederalists. So, rather than debates, we have discussions. Discussions based on fact.

When a student says, “My Mom said . . . ” – that’s not going to advance the discussion. Your Mom’s a great person, but you can’t use that as the ground you’re gonna stand on. You have to find evidence in the sources. What were the people of history going through, and what did they say? If the discussion gets really heated between two or more students, I ask them to stay after class and I ask, “are we all good now?” They have to look at each other and acknowledge that they respect each other’s opinions. I’ve never yet had it turn awful.

Livingston: We do something called “Deliberations” in my classroom. I say, “We may not all agree on all issues, but we can probably agree on something. Let’s start with what we can agree on and work forward.”

Tucker: That kind of classroom experience sounds like a model for civic life at large.

Boudell: Yes. I hate what happens on social media, when you see people tearing each other down. Knowing when to speak, and when not to, is a skill that I teach. Is the cost of using my voice worth it at this moment? If so, can I respond to your comment in a civil way? Can I ask questions to understand where you’re coming from?

Tucker: What is the most important citizenship skill you hope students learn?

Boudell: Critically thinking and listening.

Livingston: Learning how to develop their own ideas and thoughts.

Tucker: Is this program helping you figure out how to teach that?

Livingston: In the Supreme Court class I took last week, I reached the point of saying, “I don’t agree with this decision, but I can understand it.” That’s where we try to get in our classes. If we can do that, we can think about working together toward a more perfect union. The Constitution does not say “We are offering this framework to make a perfect union;” it says we’re making “a more perfect union.”

Boudell: We all have pasts that could embarrass us. We all grow. Has America changed? Yes! Tracking that becomes really important.

Tucker: What’s one way this summer at MAHG will change how you teach?

Boudell: In my course on the Founding, I realized, “Oh, my gosh, the term federalism—I’ve been defining it wrong!”

Livingston: I find myself thinking, “can I just gather the students I had last semester for a few hours to correct the information I gave them?” But as we said before, the main thing has been to underscore the importance of primary documents. It’s not what Ms. Livingston taught us today; it’s what Madison said. And what the students themselves think after reading Madison’s words.

Boudell: The other day, my husband saw the supervisor who encouraged me to enroll in MAHG. She asked him, “Is your wife okay? Is her brain exploding?”

I told my husband that from only twelve days of classes I’ve learned so many things I can bring into my teaching. I wouldn’t trade this for anything. It’s worth the three weeks I’m spending here this summer, and the three weeks next year, and the year after that, and the time I’ll spend at home in online classes. It’s worth it because of the benefit to my students.