Recreating Teaching American History Colloquium, Teacher Helps Students Learn about African American Experience in World War I

Love of history and an interest in helping young people drew Jotwan Daniels away from a planned business career and into high school teaching. He also hoped to improve on the teaching method his own teachers had used. “They viewed students as baby birds: they digested material and regurgitated it for our consumption.” Consequently, “we retained historical concepts long enough to pass the test, then forgot them. They were brokers of knowledge; I want to facilitate learning,” Daniels says.

Daniels uses the approach Teaching American History (TAH) encourages: guiding students’ conversations about primary documents. He asks students to read several accounts of one event and then draw their own conclusions. “Reading primary documents allows students to ask questions of themselves, ask questions of each other, and ultimately ask questions of history,” Daniels says.

A TAH weekend colloquium on World War I introduced Daniels to primary documents he would later use in his classroom. He enjoyed discussing these texts with the facilitator: Professor Jennifer Keene, a historian at Chapman University and a visiting faculty member in the Masters of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program at Ashland University. Instead of lecturing, Keene guided the teachers in discussing readings on the experience of soldiers in the war and of Americans on the home front. Even so, Daniels felt he “really benefited from Keene’s expertise. I also enjoyed bouncing ideas off of other teachers on how we might use the documents to recreate the colloquium for our own students.”

Daniels wrote a lesson plan based on the colloquium, tested it with his students at Summit High School in Frisco, Colorado, and then contacted Teaching American History Program Manager Jeremy Gypton to report that the lesson went very well.

He used documents highlighting the African American soldier’s experience. Students first read President Wilson’s speech announcing America’s entrance into the war, calling it a fight to “make the world safe for democracy.” Then they read an editorial in the NAACP journal Crisis by W. E. B. Dubois, who urged black men to enlist. Finally they read a letter sent to Dubois by one of those who enlisted and fought in France.

African American Sergeant Charles Isum had been quartered in a French family’s home, treated as an honored guest and invited to social events. Accepting these invitations, as Isum told Dubois, brought his arrest by American military police, who had forbidden fraternization between the black soldiers and the French locals. After the French protested, Isum was released and a threatened court martial hearing was dropped.

To provide extra historical background, Daniels showed students a video on the 369th infantry regiment—an African American force sent to fight under the command of the French. Dubbed “hellfighters” by the Germans they fiercely combatted, they captured a key railroad junction during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Upon returning home to New York City, the “Harlem Hellfighters” were honored with speeches and parades.

Nevertheless, their heroic service did not lead, as Dubois had hoped, to better economic opportunities and recognition of civil rights for African Americans. The case of Corporal Henry Johnson, who with another soldier repulsed a surprise German attack on a bridge held by US forces, illustrates the stubborn African American reality after World War I. Johnson was awarded the highest French military honor—the Croix de Guerre—and personally welcomed home by New York Governor Al Smith. Yet he died young, poor and alone, his injuries having left him unable to support himself.

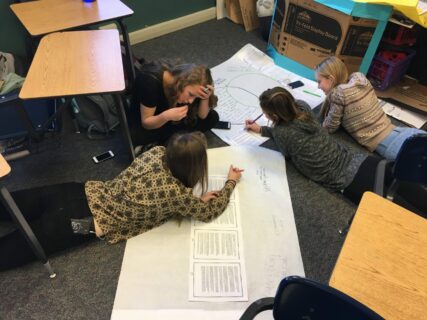

“The students I teach are still innocent,” Daniels said, “so they were shocked by what they read. But our conversations around these documents were amazing.” To prepare for discussion, students worked in pairs on a silent “collaborative annotation” exercise. They pasted copies of the documents to butcher-block paper and then wrote comments around them. “One student’s annotation would prompt a written response from his partner.” Having processed the documents silently, all were ready to join the conversation that followed.

Later, students returned to the butcher-block paper to complete a Venn diagram. Inside one circle they noted African American soldiers’ experience in France; inside the other they wrote about these soldiers’ experience in America. In the overlap between the circles they noted conditions the soldiers experienced in both countries. This exercise helped students articulate the ways that racist attitudes blinded many Americans to what the French recognized as heroic service.

Daniels believes that reading the testimony of the past, even when it shows American failures, does not teach cynicism about the American future. “History can be a little sad,” Daniels says. “But if students understand the historical background of current events, they may be better able to devise solutions to those problems today.”