Students “Unlock” Clues in Primary Documents, Finding Constitution Booklet

Joe Welch, an American history teacher at North Hills Middle School near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, relies on internet technology for access to primary historical documents. He directs his eighth graders to online libraries such as Teaching American History’s (TAH.org) collection “almost every day.” This helps students learn our nation’s history directly from those who lived it. Reading the words of earlier Americans, students empathize with the way those Americans thought and felt, relating their own life challenges to those of the past. This helps students understand themselves. Welch tells his students, “Technology and styles may change, but human emotions do not change.”

Teachers with these high goals need to step back into the role of student from time to time, to check whether their approach works. Welch did so last spring at an TAH-sponsored weekend colloquium on Alexander Hamilton’s role as advisor to George Washington.

A group of twenty teachers sat together discussing Washington and Hamilton’s speeches and letters, guided by an engaging scholar: Stephen Knott, a faculty member in TAH.org’s Master’s program at Ashland University, a presidential biographer, and a Professor at the US Naval War College. “I had not discussed history in this way since college,” Welch said. Knott helped teachers answer the questions that arise when reading primary sources: “What was Washington’s motive when he wrote this? What other contemporary events affected his thinking?” Discussing such questions pointed up those unexpected layers of meaning that Welch hopes his eighth graders will discover.

Later, Welch attended a conference on classroom technology. One workshop suggested a classroom application of the “break-out” game, in which a team of friends is locked in a room and uses clues to find a way out. In the educational version, students go to websites to find clues to open a box with multiple locks. “How can I use this to introduce students to primary sources?” Welch wondered.

Welch thought of the most important primary source he uses in his class: the US Constitution. He carries a pocket Constitution at all times. “We study it as we cover the Founding; in later lessons I pull it out and refer to it. I wanted my students to find the Constitution inside the lockbox.” So Welch reached out to his new contacts at TAH, who agreed to donate 100 copies of the booklet, enough for every student.

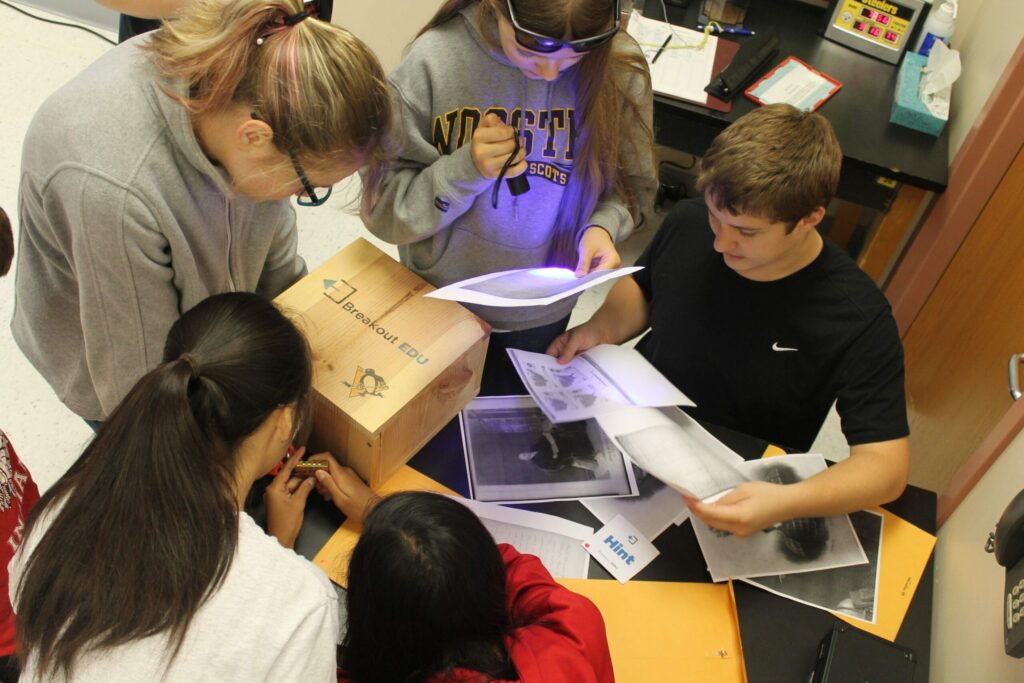

In the game Welch designed, students examined five sets of short primary sources to open six locks. Documents included short letters, speeches, images, even a hand-written Electoral College vote tally. It was early in the school year, and Welch wanted to demonstrate the range of documents historians use.

He presented a scenario: “A new President has been elected, and he wants to create his own version of American history. He is destroying all our primary source documents. But our Founding Fathers locked away one thing to prevent a tyrant from taking power and erasing our memories. What is it? Open the box to find out. You have 40 minutes until the President’s executive order takes effect.”

“It was far-fetched, but middle-schoolers ate it up,” Welch said. “I’d never seen students so eager to examine primary sources. They read each document, then read it again.”

The locks opened in different ways. One set of clues directed students to a key hidden in the room. Another lock was opened by a word; two required a combination of digits. Finding keys required making connections between documents. For example, one set of clues contained a dated copy of the Gettysburg Address and a copy of the Declaration of Independence with the date blanked out. Students realized that the first words of the Gettysburg speech, “Four score and seven years ago,” referred to 1776, the year Americans announced their independence—and also the four digits that opened the lock.

To make some clue sets, Welch pulled documents related to Western Pennsylvania. A 1794 letter from Alexander Hamilton (then Secretary of War) to Governor Thomas Mifflin, “on the necessity of an immediate March of the Militia against the Western Insurgents,” referred to the Whiskey Rebellion—an event in local history most of Welch’s students had never heard of—and yielded the clue “western” for a directional lock. As clues to the word lock (opened with the key “PITTS”), Welch pulled 18 images from the Smithsonian Learning Lab. Rapidly researching the images to discover what they had in common, students realized that playwright August Wilson and ecologist Rachel Carson were born in or near Pittsburgh, that Fred Rogers filmed his children’s program there, that the Westinghouse Company was headquartered nearby, and that Meriwether Lewis launched the keelboat he and William Clark needed for their expedition into the west on the Allegheny River, at Fort Fayette in Pittsburgh.

Since Welch had built two lockboxes, students competed in teams. This introduced another skill: collaborative reading. “They divided to conquer, then worked as groups to figure out the remaining clues.” Seven out of ten teams (in five classes) met the 40-minute deadline.

Welch designed the game to show students “that they were going to have dig underneath the surface of primary documents to find their meaning and to find connections between documents.” At the end of class, the look of triumph on students’ faces showed they had also learned that “you can really work together with your peers to accomplish something.

You can learn more about the lockbox game Welch designed here