Summer MAHG course on Adams Family Shows the American Republic Becoming an Industrial Democracy

This summer on the campus at Ashland University, teachers in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program have an opportunity to study in a single course successive generations of America’s most distinguished political family, the Adamses. Summarizing the roles the family have played, Professor Natalie Taylor says, “Four generations of the Adamses brought about a revolution, established self-government, participated in the transformation of the republic to a large-scale democracy, and then witnessed the industrialized nation take its place on the world stage.” In the interview below, Taylor explains that her course will cover not only the lives and work of seven very interesting men and women; it will illuminate political and cultural developments in the United States from the Founding through the Progressive Era. Taylor is Associate Professor of Political Science at Skidmore College, where she teaches political philosophy, including Feminist Political Thought and American Political Thought. Her publications include The Rights of Woman as Chimera: The Political Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft (2007) and an edited volume titled A Political Companion to Henry Adams (2010). You can read more about Taylor’s course, scheduled for Session 2 (July 2 – 7) here, where you will also find a link to the course syllabus and readings.

Adams family members of successive generations played key roles in American politics, from the era of the Revolution through the Civil War. Which members of the Adams family will your course cover?

Not only do the Adams family reappear in successive generations; in each generation, the members of the family who’ve played important roles in our civic life have been numerous. In fact, about five years ago, at a conference in Quincy, Massachusetts where I delivered a paper, I met a member of the family—a John Adams who today works in the State Department. Clearly, among family members there is still a sense of responsibility to engage in public service. But we’ll be studying those who’ve played prominent roles in our history.

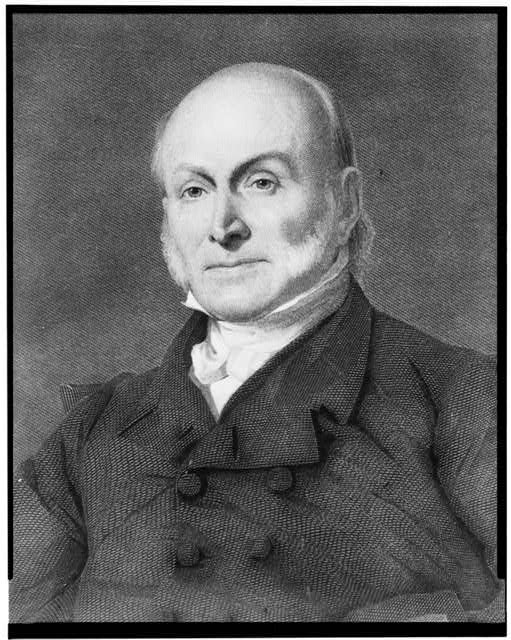

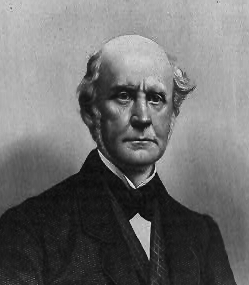

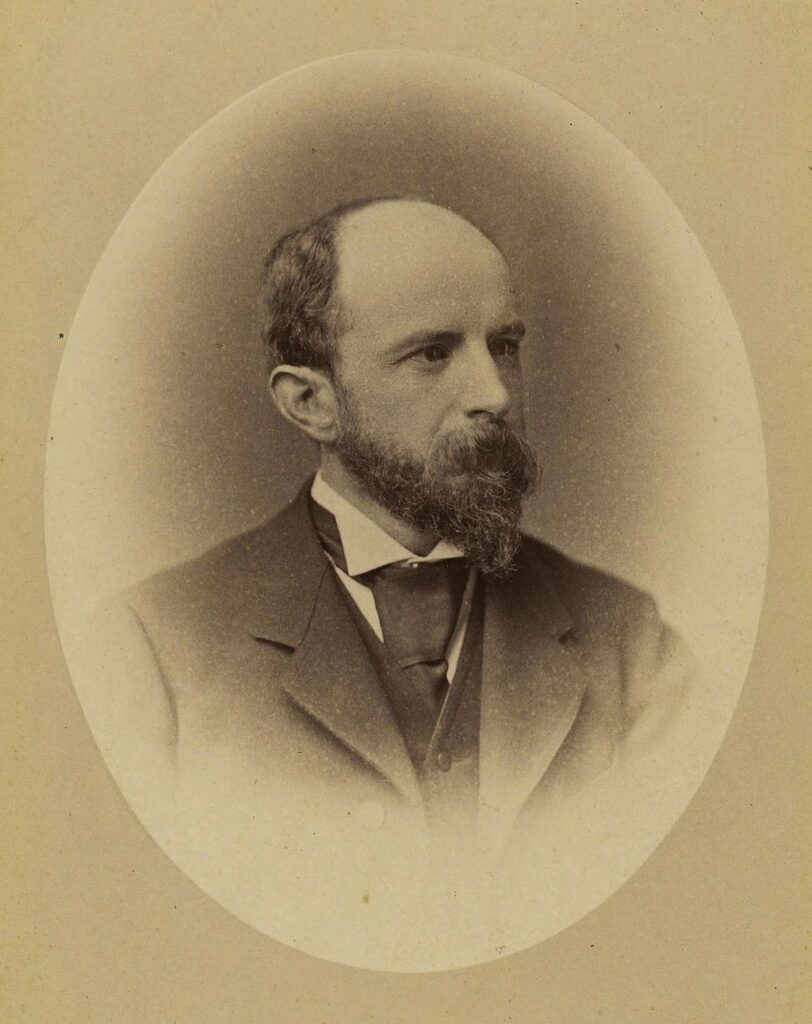

We’ll look at seven members of the family: John Adams, a key leader of the Patriot cause, Washington’s vice president and our second president; his son John Quincy, who among other roles served as our sixth president and as a long-serving member of the House; and his grandson Charles Francis, who as Lincoln’s ambassador to London helped to prevent Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. We’ll also read works by John Adams’s great-grandson Henry, who achieved renown as a man of letters, writing often about the political activity and cultural changes he witnessed during the latter decades of the 19th century and first two decades of the 20th. We’ll spend quite a bit of time thinking about the private lives of those four men, including their relationships with their wives, who are themselves rather interesting figures. We’ll read letters written by John’s wife Abigail and John Quincey’s wife Louisa Catherine.

We won’t spend time on Charles Francis’s wife, but we’ll certainly talk about Henry Adams’s wife Clover, a woman just as outspoken and intelligent as Abigail and Louisa Catherine. The novelist Henry James commented on her intelligence, calling her “a perfect Voltaire in petticoats.” Yet her life ended tragically, in suicide. Her story perhaps exemplifies the disorientation Henry himself felt as he watched America change.

So, actually, your course will begin in the Revolution and go past the Civil War; it will conclude in the Progressive Era. Will you spend time discussing the nation’s political and cultural development during its first 140 years?

That’s one theme of the course: America’s transition from a nation founded on republican principles to one that is a large-scale industrial democracy. Henry Adams, who was born in 1838 and died in 1918, spent much of his life contemplating this change. Nearing the end of his life, he felt the nation had been utterly transformed from the one that his family helped to establish. Compared to the country he knew as a child—and to the political establishment that, as an Adams, he was able to witness from the inside—America now seemed to run on a different kind of energy, in pursuit of different objectives.

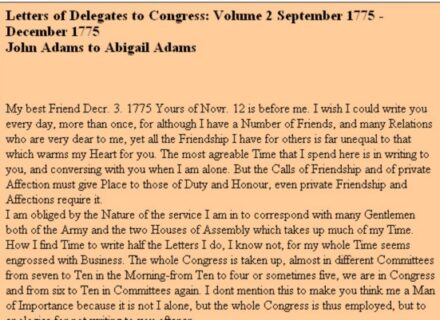

It’s interesting that Henry Adams was troubled by the progressive turn in American politics he witnessed. His great-grandfather John Adams, like most of those of the founding generation, hoped the country would achieve progress of a kind. As he wrote in a letter to home Abigail, while serving as ambassador to France, he expected his descendants to enjoy a wider realm of career choices as the American republic became more secure and stable. He said, “I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.”

There you have it—the “flowers of freedom!”

How well did John Adams predict his descendants’ futures?

I think pretty well. All of the Adams family, actually, were interested in history and contributed to recording it. John Quincy Adams kept very extensive diaries; the Library of America published those about six years ago. In the course, we’ll read portions of his diaries and also many of his letters. Charles Francis Adams wrote a biography of his father John Quincy as well as other historical works. More than his father and grandfather, Charles Francis would have preferred writing history to holding office. But as an Adams who was part of the abolition circles, he was frequently called back into duty.

The women of the family also took care to record not merely the history of their own family, but that of the nation. Abigail and Louisa Catherine certainly aided in this effort, in part as lifelong letter writers but also as diarists. They intentionally wrote for future generations, even if only for their children. One issue we’ll examine during the course is the meaning of history, and what it means for citizens to take responsibility for preserving and interpreting our national story.

Charles Francis collected the letters between Abigail and John and published them in 1840, later having them reprinted them on the centenary of the Declaration. Even in 1840, he knew people would be interested. While the men were building the nation in Philadelphia and Washington, the women back at home helped to sustain the revolutionary effort. He wants their story told as well, especially because of their critical work in educating children. In the course, we’ll read a lot of the correspondence between John and Abigail, while considering another important question: how do we raise up successive generations of self-governing citizens?

By the time we get to Henry, we see an Adams interested not only in history but in the arts. During the course, we’ll read portions of Henry’s history of the Jefferson and Madison Administrations. But Henry also wrote poetry and fiction. We’ll read his novel Democracy, which depicts Gilded Age politics through the lens of a female character loosely modeled on Henry’s wife Clover. Two of Henry’s later works—The Education of Henry Adams and Mont St. Michel and Chartres—almost defy genre categorization yet are considered masterpieces.

Henry also collected European art, as many people of means in his generation did. He did really reap the benefits of his great-grandfather’s work. Yet for most of his life he felt puzzled by the contrast between older and contemporary art—he himself became a medieval historian—just as he was puzzled by the contrast between the political traditions of the founding generation and the politics of the Progressive Era.

Many in the Adams family served as diplomats. Has that been one of their more important contributions?

Yes. It’s an interesting role for the Adamses to play, given that they are so identified with New England and particularly with Quincy. The reality is that every single one of them lived abroad for many years (even Abigail spent a few years in Paris and London during her husband’s ambassadorships). Still, when John Quincy married abroad, John and Abigail were wringing their hands at the thought of welcoming into the family a worldly English girl who grew up in aristocratic circumstances, spending many of her evenings dancing at parties. How would she ever take care of their rural New England home?

Despite the homespun republican attitudes they professed, the Adamses were really a cosmopolitan family. Perhaps, in a kind of Ben Franklin way, they cultivated their association with Quincy and New England as a way of keeping their moral bearings and inoculating their children against the corruption of the European courts. Perhaps Abigail was most responsible for that. She was the one who stayed behind, the one who insisted that the moral principles were to be found in Quincy.

Was John Quincy homeschooled by Abigail?

By Abigail, and by John, and by Thomas Jefferson, even—it takes a village! When John Quincy was about 12, his parents decided that he should travel with his father to Europe. His father was going to be Ambassador to Paris and then eventually to Holland; John Quincy went along to begin to learn the ropes of public service. Even before, when John Quincy was still at home with his mother and his father was busy in Philadelphia, John would write his son instructions about what he should study and why.

We’ll spend one session looking at Abigail as a model of republican motherhood during this time when John Quincy and his siblings were young. We’ll also discuss diary entries of John Quincy’s wife Louisa Catherine. She made a quite a harrowing journey with her little baby Charles Francis from St. Petersburg to Paris during the Napoleonic wars. John Quincy had been summoned to Paris ahead of her, leaving her to negotiate on her own the passage of her carriage through lines of troops. I expect teachers who are interested in Abigail will love Louisa Catherine—or they’ll love to hate her, because they’re very different.

It’s my impression that the Adams family, at least in the first couple of generations, had a more robust Christian faith than many of those in the founding generation.

I would say that your impression is well founded. Both John and Abigail Adams came from families of ministers. Abigail’s father was a Congregational minister and John was meant to study theology at Harvard before he switched course and studied law. They also, I think, had a closer connection to the Puritans than subsequent generations did.

When Henry lost his religious faith, he saw that not as his own personal failure but as a generational problem, coincident with the rise of science. It’s a mystery to him how a sense of the spiritual and sacred could have disappeared, but he knows that science has something to do with it. He writes about this in his beautiful book Mont St. Michel and Chartres. The disappearance of the sacred and spiritual from Adams’ experience of America is one of his two major preoccupations; the other is the transformation of the republic into a democracy. He sees that change as leading to political corruption, as leaders begin working to advance industrial and commercial interests.

Is Henry your favorite Adams?

Oh, yes! I enjoy his witty and often edgy prose. I also find his questions about the changes he observes in America rather compelling. They are questions that concern all of us as we consider the direction our political and social life is taking.