Summer Reading Ideas

We asked our faculty what books they are reading during the more relaxed months of summer. Their choices, below, show their wide-ranging interests in history, biography, and fiction. Perhaps one will inspire your next summer read!

Elizabeth Amato (Gardiner-Webb University) is enjoying the work of a master stylist in a now-neglected literary form:

“I’m reading The Letters of Evelyn Waugh (edited by Mark Amory). Evelyn Waugh is a favorite author of mine, but the immediate inspiration for picking up the volume is that this spring I read Fr. James Schall’s Another Sort of Learning in which he recommends the book as an excellent example of the lost art of letter writing. I harbor unreasonable hopes that my correspondence might be improved. Many of Waugh’s letters are written to be amusing. Often, he embellishes a story that happened to him to make it more delightful for a friend to read. Regardless, Waugh’s letters demonstrate care for words and elegance even when he relates everyday life. Moreover, it’s absorbing to read Waugh reflecting on his books. I’d recommend the book to anyone who already fancies Evelyn Waugh as an author.”

Stephen Knott (US Naval War College) recommends a timely history:

“Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939 by Volker Ullrich, a German historian. This is Volume I of a two-volume series. I read the second volume first (Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945) this past winter, and found it so well written and researched, and so chilling, that I decided to work my way backwards and read the first volume.

“Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939 by Volker Ullrich, a German historian. This is Volume I of a two-volume series. I read the second volume first (Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945) this past winter, and found it so well written and researched, and so chilling, that I decided to work my way backwards and read the first volume.

“I chose this work because I am an amateur student of the Second World War and I had read so many positive reviews of Ullrich’s work. One aspect of Ullrich’s work that I appreciate is his willingness to cite other experts and to either endorse or challenge their conclusions. But more importantly, he is a master of narrative storytelling.

“Sadly, with the rise of illiberalism around the globe, all of us have much to learn from this disturbing saga. There were so many missed opportunities to deny Hitler the power he desperately sought – too many political figures assumed they could control him and dismissed his hateful rhetoric as populist boilerplate. Sadly, he meant what he said. These same figures assumed that Hitler would adopt a more moderate approach once in office. Those who believed they could control Hitler discovered in a very short period of time just how wrong they were. This is truly a story for our times.”

David Krugler (University of Wisconsin, Platteville) recommends a biography of a World War II hero you may never have heard of:

“For my birthday I was given Jack Fairweather’s The Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated Auschwitz. It’s the overlooked, amazing story of Witold Pilecki, a Polish Army officer who, after Poland’s conquest by Germany and the Soviet Union at the start of World War II, became part of the Polish resistance. At the age of almost forty, and while married with kids, he volunteered to assume a false identity in order to get arrested by the German occupying forces and interned at Auschwitz. From inside the camp he gathered intelligence and led resistance (sabotage, even assassinations). When he learned that the Germans were preparing to make the camp into a death center to carry out the Final Solution, he pulled off the impossible: He escaped to warn the West of what was happening.

“For my birthday I was given Jack Fairweather’s The Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated Auschwitz. It’s the overlooked, amazing story of Witold Pilecki, a Polish Army officer who, after Poland’s conquest by Germany and the Soviet Union at the start of World War II, became part of the Polish resistance. At the age of almost forty, and while married with kids, he volunteered to assume a false identity in order to get arrested by the German occupying forces and interned at Auschwitz. From inside the camp he gathered intelligence and led resistance (sabotage, even assassinations). When he learned that the Germans were preparing to make the camp into a death center to carry out the Final Solution, he pulled off the impossible: He escaped to warn the West of what was happening.

“I’d recommend this to anyone interested in World War II—or to anyone looking for a well-researched history written like a thriller novel!”

Mack Mariani (Xavier University) is reading the biography of a founder whose views bear on Constitutional interpretation:

“I am reading Richard Bernstein’s The Education of John Adams, in anticipation of Bernstein’s visit to Xavier in September, when he will deliver the Constitution Day lecture. Examining Adams’ life and writings from his perspective as a legal scholar, Bernstein gives particular attention to Adams’ comments on the Constitution of 1787. His arguments are particularly relevant to the debate about originalism and how judges should think about the views of the Founders when interpreting the Constitution.”

Dr. Melissa Matthes (United States Coast Guard Academy) will read the long-buried work of a major American novelist, along with a more recent favorite:

“This summer I am planning to read Richard Wright’s previously unpublished novel, The Man Who Lived Underground. The story centers around a black man who while in police custody confesses to a crime that he did not commit. After he flees from the police station, he lives underground in the NYC sewer system. Wright said of this work, ‘I have never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration.’ I am recommending this book because it addresses ‘of the moment issues’ – violence, race and law enforcement – with the long reflective perspective of one of America’s great writers on these issues.

unpublished novel, The Man Who Lived Underground. The story centers around a black man who while in police custody confesses to a crime that he did not commit. After he flees from the police station, he lives underground in the NYC sewer system. Wright said of this work, ‘I have never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration.’ I am recommending this book because it addresses ‘of the moment issues’ – violence, race and law enforcement – with the long reflective perspective of one of America’s great writers on these issues.

“Because I live on the CT shoreline and therefore still keep a space in my bookbag for ‘summer beach reading’ I will also be re-reading India Edgehill’s Queenmaker: A Novel of King David’s Queen. Edgehill is a wonderful storyteller and she imagines the story of King David from the perspective of his often forgotten first wife, Queen Michal. As a professor of religion and politics, I enjoy novels like this: biblical stories reimagined from the perspective of often marginalized female characters. For those who want to follow this creative thread of ‘queen makers,’ Edgehill also has reimagined Sheba in Wisdom’s Daughters as well as Vashi and Esther in Game of Queens.”

“Because I live on the CT shoreline and therefore still keep a space in my bookbag for ‘summer beach reading’ I will also be re-reading India Edgehill’s Queenmaker: A Novel of King David’s Queen. Edgehill is a wonderful storyteller and she imagines the story of King David from the perspective of his often forgotten first wife, Queen Michal. As a professor of religion and politics, I enjoy novels like this: biblical stories reimagined from the perspective of often marginalized female characters. For those who want to follow this creative thread of ‘queen makers,’ Edgehill also has reimagined Sheba in Wisdom’s Daughters as well as Vashi and Esther in Game of Queens.”

Dan Monroe (Millikin University) recommends a concise new biography of Frederic Douglass and a history of the Whig Party. Dan is also considering new perspectives on the Lincolns’ marriage:

“I teach an honors course on Douglass at Millikin University. Timothy Sandefur’s 140 page-book, Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man will be included as required reading in my course. Sandefur notes that Douglass had strong libertarian sentiments, an important perspective.

“I’m reviewing a new book on the Whigs for the Journal of American History: Joseph W. Pearson, The Whigs’ America: Middle-Class Political Thought in the Age of Jackson and Clay. It is a thoughtful survey of Whig political and cultural attitudes and a fine contribution to the literature.

“I recently finished reading Daniel Mark Epstein, The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage as a prelude to reading Michael Burlingame’s book on the Lincoln marriage, just published. Epstein is an elegant writer, and his conclusions are sound. There’s quite a historiography on Mary and on the Lincoln’s union; I look forward to consuming Burlingame’s study—An American Marriage: The Untold Story of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd—this summer too. It’s important to understand what is going on in the lives of historical figures; the Lincolns suffered the deaths of two sons while Lincoln was alive, and Mary had a reputation for difficult behavior. I’m interested in Burlingame’s take.”

John Moser (Ashland University) plans to read about Stalin’s role in shaping World War II:

“I’m excited about the recent publication of Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, by one of my favorite historians, Sean McMeekin. But since I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, I’ll recommend his 2017 book, The Russian Revolution: A New History, which emphasizes that the accomplishment of Lenin and his Bolsheviks in October 1917 should be more accurately described as a coup, not a revolution. Although its success depended to a certain extent on the tactics of Lenin, Trotsky, and several other leading revolutionaries, it rested even more on the Germans, who invested the modern equivalent of $1 billion in Lenin’s effort to knock Russia out of World War I. The Bolsheviks also had the benefit of incompetent opponents, most notably Alexander Kerensky, whose ‘no enemies on the left’ attitude led him to turn to Lenin to help protect against a wholly imaginary rightist plot. In any event, McMeekin leaves no doubt that the regime the Bolsheviks established was guilty of mass murder on a level unparalleled in modern European history.”

Eric Pullin (Carthage College) is reading a history that questions the notion of “objective journalism” by putting it into the context of espionage:

“The connection between private-state networks has always fascinated me, and the notion that there is something we can call ‘objective journalism’ has always troubled me. Steven T. Usdin’s Bureau of Spies: The Secret Connections between Espionage and Journalism discusses the history of how spies, posing as journalists in Washington, have secretly engaged in gathering vital intelligence, spreading propaganda, and promoting false narratives. During the twentieth century, ‘journalists’ from Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, the Soviet Union, and even Great Britain hid behind journalistic covers as they both worked as spies and shaped the very ways in which the news was reported. By examining journalism as it relates to foreign affairs, the book essentially relates that ‘fake news’ is not new to the American media.

Without engaging in hysterics or in conspiracist thinking, Usdin examines how we think we know what we know. His work relies upon evidence and documented instances of journalistic shenanigans.”

Eric Sands (Berry College) is reading “a probing and in-depth account of the framing of the executive branch of government”:

Eric Sands (Berry College) is reading “a probing and in-depth account of the framing of the executive branch of government”:

“In The President Who Would Not Be King: Executive Power Under the Constitution Michael W. McConnell covers the work of the framers in constructing the American presidency. He focuses on what parts they took from the British monarchy and what parts they stripped in order to ensure that the president would not become a king. The book aims to illuminate what powers are possessed by the president that are subject to congressional control and what powers the president possesses at his full discretion.

“Anyone interested in the presidency or the work of the founding fathers, not to mention the founding more generally, would find this book of value.”

David Tucker (Ashbrook Senior Fellow and General Editor of the Core Document Collections, Teaching American History) is reading biographies in preparation for writing a history of America in the Age of Vietnam:

David Tucker (Ashbrook Senior Fellow and General Editor of the Core Document Collections, Teaching American History) is reading biographies in preparation for writing a history of America in the Age of Vietnam:

“I just finished Frederik Logevall’s JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917-1956. I’m now reading Jean Edward Smith’s Eisenhower in War and Peace. Citizens in a republic should understand the motives of the ambitious. For that reason, Jefferson argued that history should be a major part of the curriculum in all schools. Biographies are pretty good, too. These two show there are important differences among the ambitious.”

Robert Wylie (Ashland University) recommends a fictional depiction of the lives of intellectuals persecuted during Mao’s attempt to reorganize the economy of rural China:

“Yan Lianke’s The Four Books (2011, trans. 2015) is a raw and even grisly novel about intellectuals who strive, sell one another out, suffer, and starve in a re-education camp during the “Great Leap Forward” and the resultant Great Chinese Famine that began in 1959. The “four books” of the title are fictional fragments in a new assemblage: an informant’s diary, the informant’s magical-realist retelling of the famine, another anonymous mythical retelling of the famine, and a Buddhist apologia for suffering written by one of the imprisoned scholars. The reader is left to ponder who among the survivors arranges the compilation, and why. In the background is the economic absurdity of Maoist central planning, one of history’s most horrific artificial disasters, and the fine line between civilization and barbarism. This puzzling novel by China’s most controversial author is not for the squeamish!

“Yan Lianke’s The Four Books (2011, trans. 2015) is a raw and even grisly novel about intellectuals who strive, sell one another out, suffer, and starve in a re-education camp during the “Great Leap Forward” and the resultant Great Chinese Famine that began in 1959. The “four books” of the title are fictional fragments in a new assemblage: an informant’s diary, the informant’s magical-realist retelling of the famine, another anonymous mythical retelling of the famine, and a Buddhist apologia for suffering written by one of the imprisoned scholars. The reader is left to ponder who among the survivors arranges the compilation, and why. In the background is the economic absurdity of Maoist central planning, one of history’s most horrific artificial disasters, and the fine line between civilization and barbarism. This puzzling novel by China’s most controversial author is not for the squeamish!

And Here are More Book Recommendations, from our Staff

Amanda Bryan (Editorial Assistant, Teaching American History) recommends a book that explores the “Redeemer period of Southern history and the ‘New South’ that resulted:

“Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. shows how the failures of Reconstruction led to the creation of Jim Crow laws and the spread of white supremacy ideology—while also prompting the cultural movements that arose to counter this: the Harlem Renaissance and the ‘New Negro.’ The book feels timely and relevant. I think it gives historical context for today’s debate over policing laws and voting rights access.”

and the Rise of Jim Crow by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. shows how the failures of Reconstruction led to the creation of Jim Crow laws and the spread of white supremacy ideology—while also prompting the cultural movements that arose to counter this: the Harlem Renaissance and the ‘New Negro.’ The book feels timely and relevant. I think it gives historical context for today’s debate over policing laws and voting rights access.”

Jeremy Gypton (Teacher Programs Manager, Teaching American History) has discovered an engrossing new World War II history:

“I recommend MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific, by Walter Borneman. In over 500 pages, Borneman sustains an engaging narrative, never getting lost in details. MacArthur was a complicated man who left an equally complicated legacy. Borneman describes his faults and failures, as well as his accomplishments. He analyzes and, to some extent, explains MacArthur, without judging him—this is neither a fawning tribute nor scathing rebuke from an armchair general. If you’d like to better understand World War II in the Pacific, get a good sense of military-political relations during the war, and learn more about how individuals shaped that conflict, this is a good book.”

“I recommend MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific, by Walter Borneman. In over 500 pages, Borneman sustains an engaging narrative, never getting lost in details. MacArthur was a complicated man who left an equally complicated legacy. Borneman describes his faults and failures, as well as his accomplishments. He analyzes and, to some extent, explains MacArthur, without judging him—this is neither a fawning tribute nor scathing rebuke from an armchair general. If you’d like to better understand World War II in the Pacific, get a good sense of military-political relations during the war, and learn more about how individuals shaped that conflict, this is a good book.”

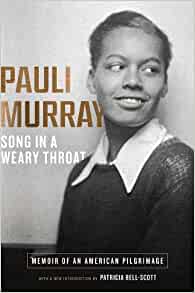

Ellen Tucker (Publications Editor, Teaching American History) has been reading the autobiography of a woman whose contributions to the civil rights efforts of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s should be better known:

“Pauli Murray’s Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage tells a remarkable story, not merely because Murray’s life previews the celebrated ‘firsts’ of others. As a law student at Howard in the 1930s, she helped stage sit-ins to desegregate a popular restaurant and suggested, 15 years before Brown v. Board of Education, the legal strategy Thurgood Marshall would follow in that case. She was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in the late 1940s. Asked to produce a pamphlet for the League of Women Voters outlining the variations in state segregation laws, she wrote a 12,000-page directory that Marshall and his team of lawyers would consult throughout their desegregation work. The book recounts her friendship with and influence on Eleanor Roosevelt, as well as the stories of other courageous activists I’d never heard of.”

“Pauli Murray’s Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage tells a remarkable story, not merely because Murray’s life previews the celebrated ‘firsts’ of others. As a law student at Howard in the 1930s, she helped stage sit-ins to desegregate a popular restaurant and suggested, 15 years before Brown v. Board of Education, the legal strategy Thurgood Marshall would follow in that case. She was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in the late 1940s. Asked to produce a pamphlet for the League of Women Voters outlining the variations in state segregation laws, she wrote a 12,000-page directory that Marshall and his team of lawyers would consult throughout their desegregation work. The book recounts her friendship with and influence on Eleanor Roosevelt, as well as the stories of other courageous activists I’d never heard of.”