Pennsylvania Teacher Testifies to Benjamin Franklin's Wonderful Life

Talk with teachers participating in TAH.org’s programs, and you learn that many have cultivated a deep knowledge of the history of their states, counties, and towns. Local history it is not emphasized in most school curricula. Yet teachers find that pointing students toward this history can help students make connections between past and present. It also encourages civic-mindedness, helping students to understand American government as a federal system, in which citizens take responsibility for local and state government.

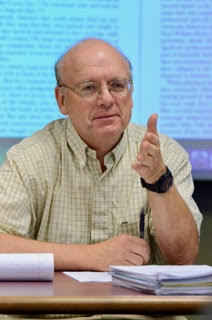

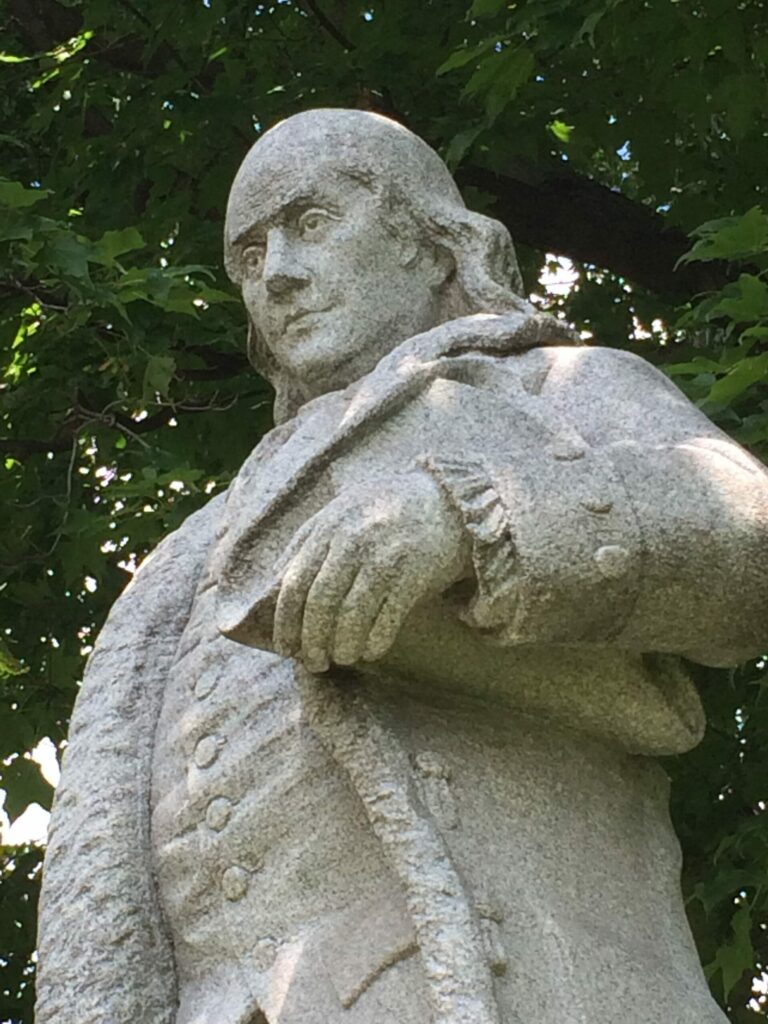

Teachers who bring knowledge of their specific region to Ashbrook Masters seminars sometimes instruct the faculty. Professor Christopher Flannery speaks of a remarkable moment in a class he taught on the writings of Benjamin Franklin. In his Autobiography, Franklin mentions his brief military service during the French and Indian War. A seminar student – Mike Feifel, a teacher at Lehighton Area High School, near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – offered Flannery and classmates an in-depth account of this episode.

Feifel explained that at the outset of the war, Franklin, as Pennsylvania representative to the continental Albany Congress, had attempted to organize a united governing council and militia for the colonies. The royal governor had not accepted his plan, and the threat posed by French-allied native American tribes to settlers along the frontier persisted.

Some of these settlers were Moravian missionaries who had founded a settlement called New Gnadenhutten – at the site of present-day Lehighton – for British-allied Indians, members of the Lenni Lenape tribe. Considered traitors by the Indians now fighting alongside the French to oust the British settlers, the Lenni Lenape had been hounded from their traditional hunting grounds. The Moravians offered these native Americans their “Huts of Mercy” settlement, providing instruction in the gospel along with a stable community. They helped the Lenni Lenape build homes, while living themselves in one mission house just across the Lehigh River.

On November 24, 1755, the Moravians were eating dinner when a party of hostile Indians attacked. The Moravians were pacifists. Those not immediately killed fled to the attic, dying when the Indians set fire to the house.

“I pass by the site every day on my way to school,” Feifel said. The spot is marked with a marble burial stone and an historical placard that tells the story of the massacre.

The alarm caused by the massacre and a failed retaliation forced Deputy Governor Robert Morris to act. He gave Franklin the title of Colonel and put him in charge of frontier defense. A highly capable administrator and communicator, Franklin recounts in his autobiography how he had raised supplies from Pennsylvania farmers for British General Bratton’s earlier disastrous venture to retake Fort Duquesne. However, he says, “I had not so good an opinion of my military Abilities as [Governor Morris] professed to have.”

“Franklin had not spent a day of his life in a military campaign,” said Feifel, who’s done independent research in Franklin’s letters. Yet Franklin traveled to the frontier settlement of Bethlehem, mustered troops, and planned an attack on the tribe who had destroyed the Gnadenhutten settlement. “On the morning of his 50th birthday, Franklin was about to set out when he got word that muskets he had brought and supplied settlers with had failed to fire during another Indian attack.” American muskets required gunpowder that didn’t ignite in wet weather. “Franklin set out anyway, but then, as his soldiers marched through a narrow, wooded gorge, he saw they were vulnerable to hidden attackers.” He ordered a retreat.

Instead of going to meet the foe, Franklin resolved to build forts. These became Fort Allen, Fort Franklin, and Fort Norris, and offered strongholds to which settlers could run when attacked. “It was a huge advance for the undefended area,” Feifel told his classmates.

“In 1758, the Treaty of Easton brought a truce between British settlers and the hostile tribes. The last Indian massacre in the area occurred in 1763,” as the French and Indian War neared conclusion. Feifel credits Franklin’s initiative and leadership with securing the Pennsylvania frontier.

He pointed out to the seminar that this region would be critical to the nation’s industrialization. Here, anthracite coal would be discovered, and Josiah White would build canal to take coal to Philadelphia. Coal would later fuel the steel industry that grew up around Bethlehem. The area would also become the birthplace of organized labor, where the “Molly Maguires” first organized.

White would donate some of his profits from Lehigh River navigation to found schools for Native Americans. One of these, Carlisle Industrial Indian School (now Carlisle College), educated the great athlete Jim Thorpe.

“All of this happened because of what Franklin did,” Feifel told fellow students in Flannery’s Ashbrook seminar.