Thanksgiving Proclamations in the Civil War

If he follows long-standing tradition, then sometime this coming November, President Trump will issue a proclamation for a Day of Thanksgiving as his predecessors have done for generations. It will likely be written to inspire the nation and will include reminders of the origins of our very American Thanksgiving celebrations and will urge all Americans to feel gratitude for our myriad blessings, etc.

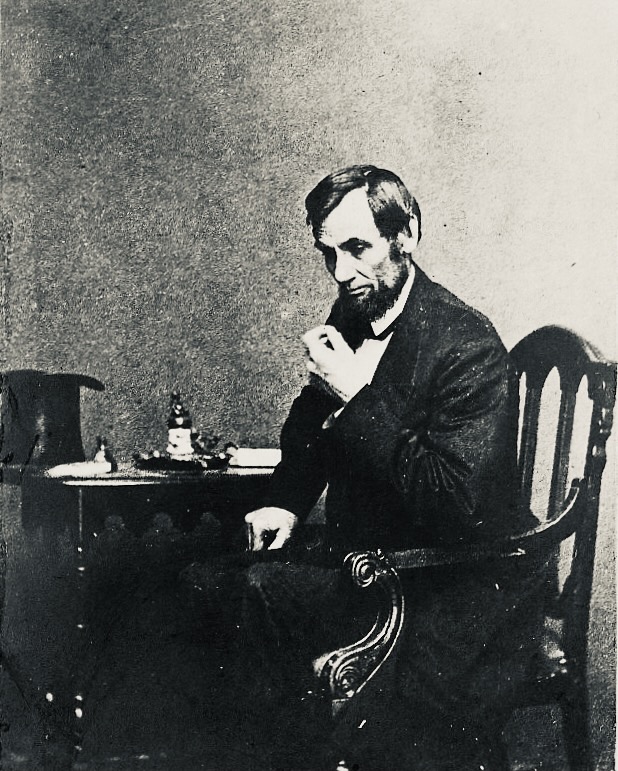

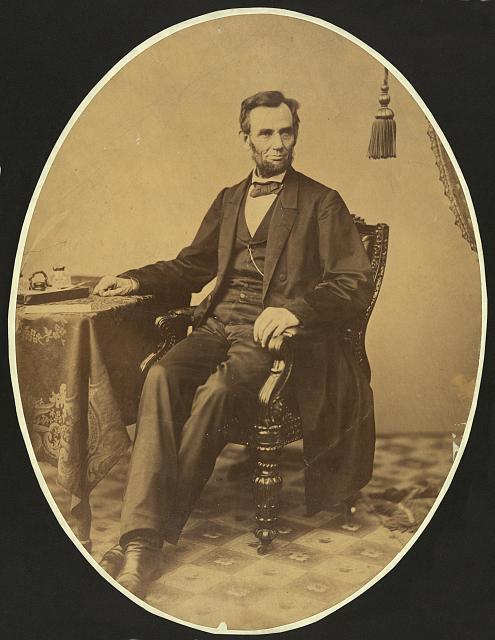

Over the years, Presidents have issued many such proclamations, and in years of peace and prosperity, they come together easily. But what do presidents have to say in the terrible times, for example, when the nation is at war? How do they inspire Americans to celebrate our heritage or way of life, or any other joys, when life itself seems a real struggle? Certainly, if any American president faced this problem, it was Abraham Lincoln, whose term of office began with the Civil War. The messages he issued over the years of that conflict did, in fact, provide the genesis of our American tradition of Thanksgiving Day.

It is hard to imagine all the challenges Lincoln had to consider while writing his first Thanksgiving Proclamation. From the day of his inauguration, Lincoln had to deal with secession, constant threats, criticism from political friends and foes alike, and, of course, the war. Union Armies in the east had suffered terrible losses at Bull Run (July 1861) and at Shiloh (April 1862), in Tennessee, among others. Fortunately, other news from the Western Theater was better. In his message of April 10, 1862, the President focused on the victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and the capture of New Orleans as he urged Americans to both “acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father for these inestimable blessings,” and to “implore spiritual consolation in behalf of all who have been brought into affliction by the casualties and calamities of sedition and civil war….” His brief proclamation finishes with a hopeful plea for Americans to pray for “restoration of peace, harmony, and unity throughout our borders.” This last phrase is in keeping with Lincoln’s deeply held desire to bring peace to the entire nation by ending the war as quickly as possible, though it is possible he was also offering the olive branch to dissident factions throughout the Union.

Interestingly, on September 4, 1862, President Jefferson Davis of the Confederate States of America (CSA) also issued a proclamation celebrating “Victory in Battle,” referring to those Southern successes noted above. Like Lincoln, he made no references to the CSA’s losses in the west as he invited southerners “once more to His footstool, not now in the garb of fasting and sorrow, but with joy and gladness, to render thanks for the great mercies received at His hand.” While Davis issued other proclamations in the course of his term, this appears to be his only call for an actual day of Thanksgiving.

As the conflict wore on, Lincoln’s tone became a little more hopeful. In 1863, he issued two proclamations. The first, written on July 15, 1863, followed on the Union successes at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and cited “victories on land and on the sea so signal and so effective as to furnish reasonable grounds for augmented confidence that the Union of these States will be maintained, their Constitution preserved, and their peace and prosperity permanently restored.” He also urged the people of the North to offer “homage due to the Divine Majesty for the wonderful things He has done in the nation’s behalf and invoke the influence of His Holy Spirit to subdue the anger which has produced and so long sustained a needless and cruel rebellion.” Then, on October 3 of the same year, President Lincoln issued his most famous Thanksgiving Proclamation, formally establishing the date for that holiday in American culture. This time, his comments were more general, urging Americans to recognize that even in the “midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity… order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere,” Without naming specific battles as in the past, he also commented that the “theater of military conflict….has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.” He closed by asking Americans to “set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father.”

On October 20, 1864 he celebrated “many and signal victories over the enemy” along with the general economic health of the nation and again named the last Thursday in November as “a day of thanksgiving and praise to Almighty God,” asking his fellow citizens to “offer up penitent and fervent prayer and supplications to the Great Disposer of Events for a return of the inestimable blessings of peace, union, and harmony throughout the land.” (He even referenced the Emancipation Proclamation, issued earlier that year thanking the Almighty for augmenting “our free population by emancipation and by immigration.”)

It is worth taking a moment to consider Lincoln’s tone and language in all these proclamations. Though historians debate Lincoln’s personal beliefs, he read his Bible religiously (no pun intended), often quoting it in public documents and using frequent references to God throughout his writings. But he was careful to keep his comments general and tolerant in nature. For example, in the Proclamation of 1862, he urged Americans to gather in their “accustomed places of public worship.” He expanded on this theme in 1863 by suggesting they come together to give thanks in their “customary places of worship and in the forms approved by their own consciences.” Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamations are important moments in his “civic religion” approach, an attempt to appeal to the common elements of faith among all Americans without favoring one denomination over another. There is no doubt he believed in God and in God’s role in the success or failure of the Union in the Civil War (and the overall success of the United States as a nation), but he shows no interest in telling people how to specifically worship or thank that God.

Lincoln’s Oct 20th Proclamation was, of course, his final one, as he was assassinated on April 14, 1865. It would be a fascinating exercise to imagine what he might have said on Thanksgiving of that year, with the Civil War ended, but we will never know. What we do know is that all his efforts blessed us with a national holiday which, no matter what your particular faith system may be, gives us all a day to remember and be grateful for our blessings, including the leadership of Abraham Lincoln in our darkest times.

List of Thanksgiving Proclamations in our library

· George Washington, 1789

· Abraham Lincoln, 1862

· Abraham Lincoln, 1863

· Abraham Lincoln, October 1864

· George W. Bush, 2001

Rusty Eder is a Teacher Partner with Teaching American History and the History Chair, Academy Historian and Dean of Faculty at West Nottingham Academy.