The 14th Amendment: A "Mini-Constitution"

As pivotal a constitutional event as it was, the Thirteenth Amendment’s abolition of slavery initially accomplished less than its supporters had hoped — substantially due to President Lincoln’s successor Andrew Johnson’s opposition to congressional Reconstruction, as well as unyielding resistance from the southern establishment. The congressional response to these obstacles resulted in the Fourteenth Amendment. With three more sections than the Thirteenth Amendment and over NINE times the words, the Fourteenth is the longest, most complex, and most litigated amendment of our Constitution.

Many of the Thirteenth Amendment’s original supporters considered its key statement (“neither slavery nor involuntary servitude … shall exist within the United States“) a sufficient expression of principle to guide Reconstruction. They recognized slavery as the core root of disunion, so the Thirteenth Amendment’s proclamation seemed a fundamental platform to address both philosophical and institutional issues — to transform, in Representative Thaddeus Stevens’s words, the “whole fabric of southern society.” Since slavery permeated that fabric, a denunciation of it could redefine constitutional matters of powers, of rights, and of structure in southern society. But the southern establishment staunchly resisted any significant change, intending to maintain the status quo as closely as possible. Before the amendment was even ratified, southern governments began instituting black codes, which legally subordinated African Americans and frequently denied them protections enshrined in the federal Bill of Rights. Disparate application of the Bill of Rights was constitutional under the Supreme Court’s 1833 case Barron v. Baltimore, which determined that the Bill of Rights applied only to federal law — not state or local action. Furthermore, black codes frequently exploited the criminal exemption in the Thirteenth Amendment (whereby “punishment for crime” allowed governments to impose involuntary servitude) as a loophole to criminalize actions protected in the Bill of Rights when performed by black people (e.g. public assembly above certain numeric thresholds, bearing arms, public speech or preaching without permission, etc.). These practices outraged congressional Republicans, who committed to crafting a legally binding response.

Enter Representative John Bingham of Ohio, now known as the “father of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Bingham had served eight years in Congress fighting against the expansion of southern “slave power” before losing his seat in a redrawn district after the 1862 elections. During his single-term congressional hiatus, in the midst of the Civil War, Bingham’s friendship with fellow Whig-turned-Republican Abraham Lincoln led to various legal roles in the administration — work that ideally positioned him to regain his seat in the Republican wave accompanying Lincoln’s 1864 reelection. Even before the outrages of the black codes, Bingham was convinced that Reconstruction would require “[constitutional] limitations upon the States in favor of the personal liberty of all citizens of the Republic.” This conviction made him a logical champion for a new Reconstruction amendment.

In February of 1866 Bingham proposed his new amendment, stating that “The Congress shall have the power to make all laws necessary and proper to secure to citizens of each state all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states, and to all persons in the several states equal protection of life, liberty and property.” However, Bingham’s Republican colleagues hesitated, wary of the sweeping language and unconvinced that they had sufficient majorities to pass and ratify it. Still, certain of the urgent need to counteract Southern backlash, they turned to an intermediate recourse that could protect freedpeople while asserting their rights and role in post-emancipation society: the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This volley against the black codes approximated Bingham’s vision, legislating a national definition of citizenship and asserting “full and equal” legal protections that superseded “any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to the contrary.” In this act, they hoped to ensure that neither hostile laws nor norms would obstruct the necessary course of civil equality.

The motivation to return to the more permanent amendment process came quicker than anticipated, and from an unexpected place: President Johnson’s March 1866 veto of Congress’s Civil Rights Act. Calling the bill “fraught with evil,” Johnson rebuked its citizenship expansions and insisted that it interfered with market forces that would more naturally realign the civil order. While congressional Republicans knew that Johnson did not share the boldest parts of their Reconstruction vision (which they’d kept out of the law), they were surprised by his rebuff. Galvanized, they mustered supermajorities to override Johnson’s veto — the first major veto override in federal congressional history — and swiftly returned to amendment deliberations.

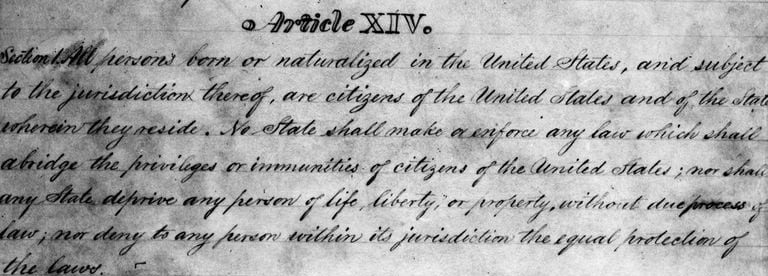

By the beginning of May 1866, Congress had the Fourteenth Amendment in near-final form for debate. Congressional records show that, then as now, the greatest energy focused on the first section:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This section would secure the principles of the Civil Rights Act in the Constitution — in then-Representative (and future President) James Garfield’s words, “lifting [the Civil Rights Act] above the reach of political strife, beyond … plots and machinations of any party.” Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan echoed Bingham’s insistence that Section 1 nationalized “the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments” of the Bill of Rights — a process we now call incorporation. Further, Section 1’s establishment of birthright citizenship overturned the Supreme Court’s notorious 1857 Dred Scott decision, which had deemed black people ineligible for citizenship, and hence beneath the protection of federal law.

The remainder of the Fourteenth Amendment became a vessel to resolve various Reconstruction complications. Section 2 presented a new representation formula that eliminated the obsolete three-fifths clause of the original Constitution, and penalized states for denying any male citizens the right to vote by proportionally reducing their congressional representation (alas, this clause was ignored in practice once Reconstruction was overthrown and Jim Crow law overtook the South). Section 3 placed restrictions on former Rebels who had held political offices before the war. Section 4 dealt with financial matters, prohibiting Confederate debt payment while guaranteeing Union debt payment, and refusing any future compensation to former slaveholders. Finally, Section 5 reiterated the language that closed the Thirteenth Amendment, asserting congressional enforcement power.

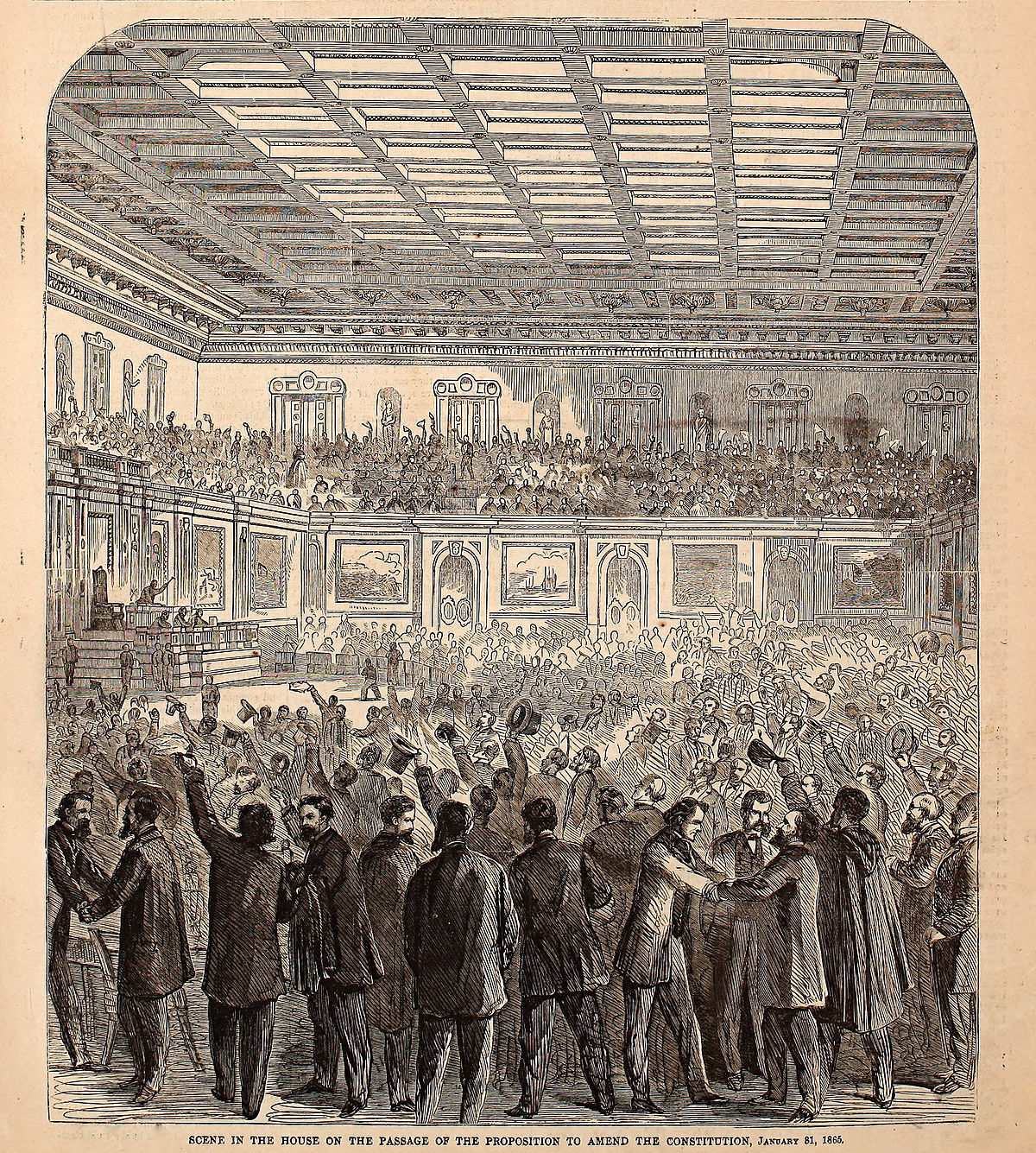

Opposition to the amendment during debate heavily focused on threats to states’ rights as well as to white rule. Representative Andrew Rogers (D-NJ), the most cited congressional opponent, attacked the amendment as a “program of disunion … most dangerous to liberty … [which] destroys the elementary principles of the States” as well as America’s status as a “Government made for white men and white women.” Senator (and future Vice President) Thomas Hendricks (D-IN) found new threats to federalism in the enforcement clause of the Fourteenth Amendment that he somehow had not seen in the exact same words of the Thirteenth Amendment: “When these words were used in the [Thirteenth] amendment they [seemed] harmless; but [now] there has been claimed for them such force and scope … that Congress might … crown the Federal Government with absolute and despotic power.” But these complaints were a distinct minority. The Republicans had crafted the amendment through compromises between their radical and moderate factions, and the urgency of countering political and social resistance was pressing. The Fourteenth Amendment passed both chambers of Congress with clear supermajorities — the Senate on June 8, 1866 by a 33-11 vote, and the House on June 13, 1866 by a 120-32 vote.

More than any amendment before or since, the US Constitution became a different document after the Fourteenth Amendment. Its various provisions have been reinterpreted over time, its role in American life changing with the power and influence of the interpreters. The amendment’s scope extended beyond empowering freedpeople and restraining Confederates in short order: the Supreme Court’s first major Fourteenth Amendment decision actually involved an association of white butchers in New Orleans, The Slaughter-House Cases (1873). A little over a decade later, after the Court announced its own shift away from Reconstruction, it extended Fourteenth Amendment protections to corporations as legal “persons” — a key source of legal protection, and controversy, to this day. During the Civil Rights Movement, activists and legal strategists demanded that the federal government apply the enforcement power of the Fourteenth Amendment and revisit the equal-citizenship roots of the amendment — both emphases that had been dormant since the end of Reconstruction. These demands helped set legal conditions for the broader rights revolution of the 1960s.

And the Fourteenth Amendment permeates current political events, cropping up in predictable and unpredictable ways, in mainstream and marginal arguments, across the political spectrum, through discussions of the debt limit, vote suppression, affirmative action, birthright citizenship, the January 6, 2021 Capitol riot, and more. Unsurprisingly, considering the numerous issues it reaches, many Fourteenth Amendment supporters consider it (in legal scholar John Witt’s phrasing) a “mini-constitution” unto itself, embedded within the original. The historical context and modern applications of the Fourteenth Amendment show that tackling the challenges and realizing the possibilities of reconstruction demanded a reimagining of the federal Constitution — an ongoing process to this day.

Malik Ali, a James Madison Fellow and 2017 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, is Tukman Distinguished Teacher of History at the Branson School in Ross, California