The Bear Flag Republic: 175th Anniversary

On June 14, 1846, 175 years ago, north of a small mission town called San Francisco, a group of American settlers declared the existence of a California republic, fashioning a flag from a sheet of cloth that happened to be at hand. The flag was emblazoned with a bear and a star (some said the star was meant to recall the Lone Star Republic of Texas), and the republic became known as the Bear Flag Republic. The republic’s life was as brief as its flag was impromptu, yet it was a step toward establishing the eventual state of California

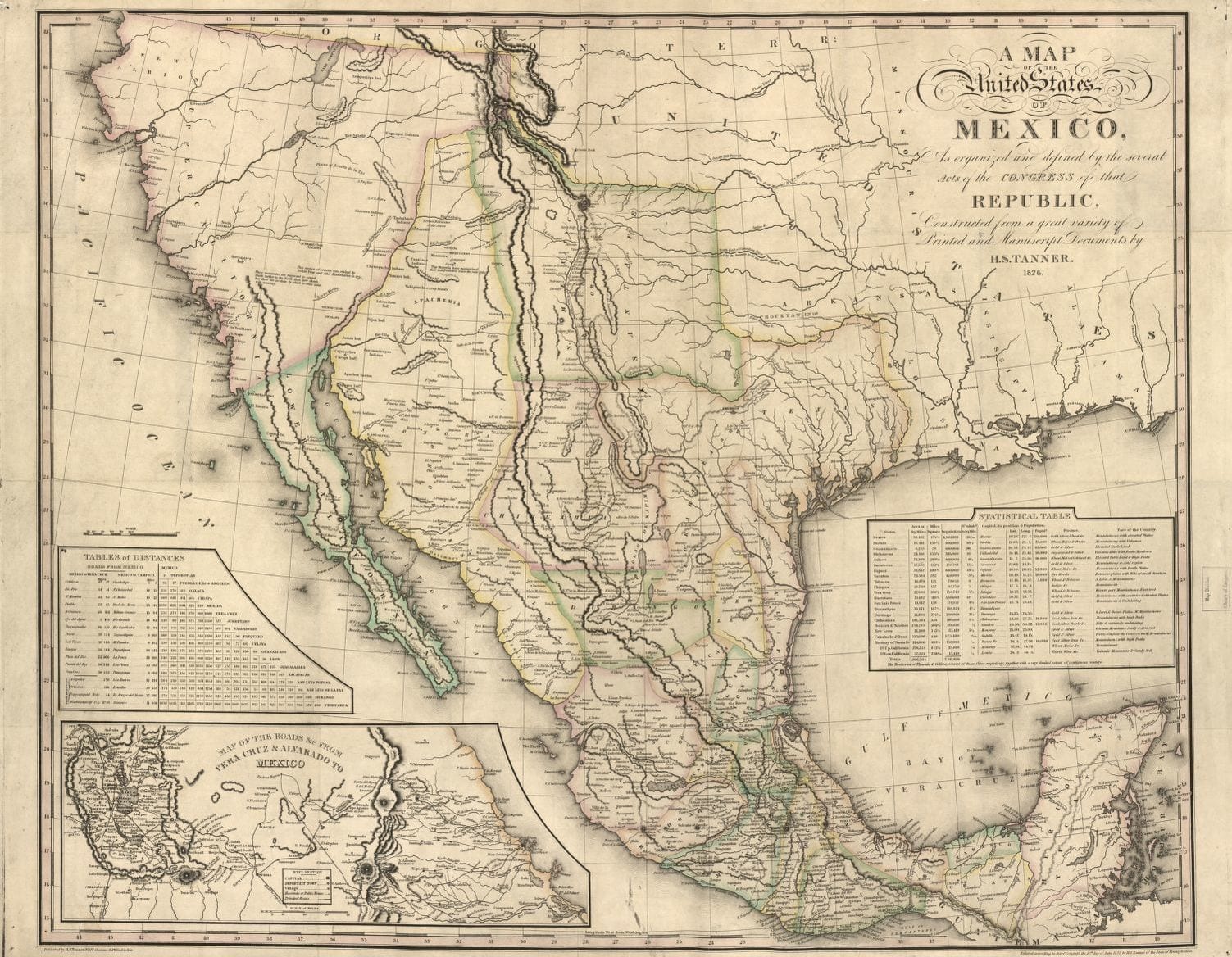

The occasion for raising the bear flag was the capture of a small garrison representing the authority of Mexico, independent of Spain since 1821, but with only scant control of its provinces of upper and lower California. The settlement of Los Angeles was 1500 miles from Mexico City; San Francisco, a further 400 miles north. But the distance was not the only issue. Between 1821 and 1846, Mexico experienced considerable political turbulence. In addition, rivalries between northern and southern Californians or Californios, as the Spanish-speaking inhabitants of California were called, complicated Mexican control. In part because of the ineffectiveness of the Mexican government, many Californios looked favorably on the looming presence of the United States. When the American settlers approached the leader of the Mexican garrison, a Californio, he invited them in for lunch.

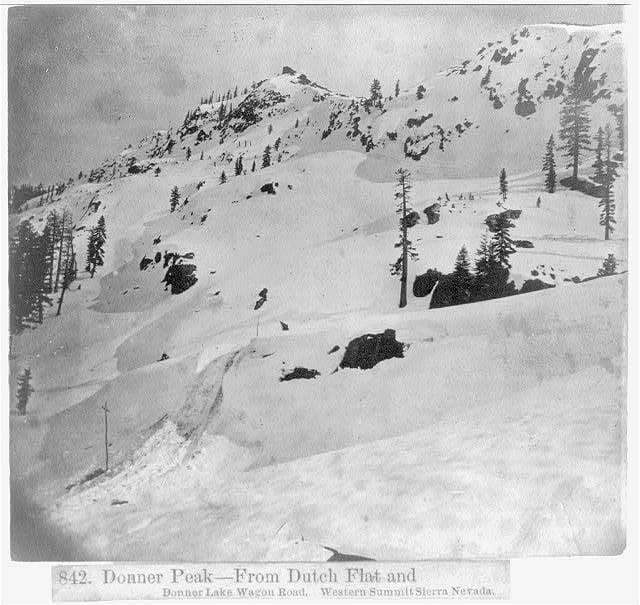

The first American overland settlers came to California in the early 1840s on the California Trail over the Sierra Nevada mountains. This trail was an offshoot of the Oregon Trail and included Donner pass, north of Lake Tahoe and along the current route of Interstate 80, where the infamous Donner party was trapped by early snow in 1846. American settlers in California were preceded by trappers, like the legendary Jedidiah Smith, who traversed the mountains as early as 1826 to hunt beaver in California. Other Americans reached California by sea since California ports, especially Monterey, were provisioning and trading stops on the route to China pioneered by New England merchants in the 1780s.

Americans were not the only ones interested in the territory that became the state of California. Despite the proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine (1823), English, French, and Russian adventurers, with various levels of open and secret support from their governments, planned settlements in the territory to take advantage of Mexican weakness. An Irish priest, with the backing of the Catholic bishop in Mexico City, proposed to the Mexican government the settlement of thousands of Irish Catholics in California to prevent what he called American “Methodist wolves” from devouring the place. (This is an interesting example of the now largely forgotten competition between the Catholic Church and the American Protestant establishment for control of western souls.)

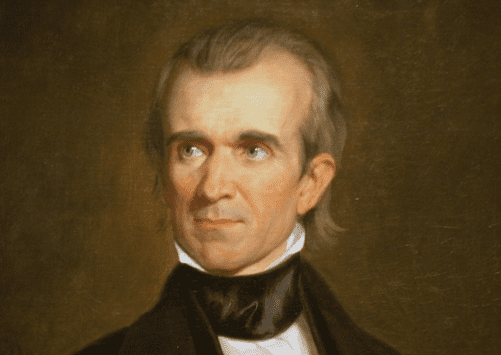

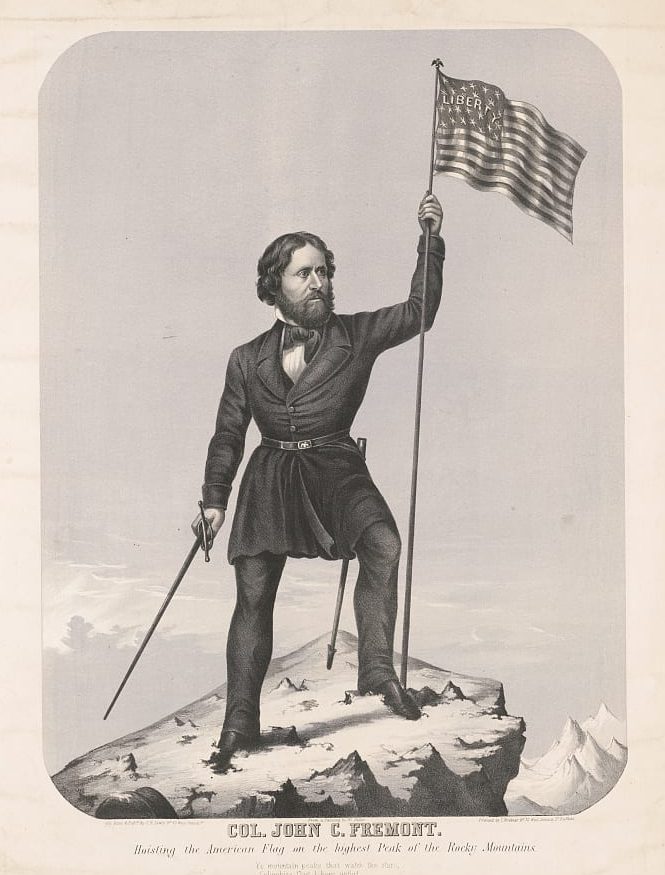

The events leading to and following the establishment of the Bear Flag Republic took place, of course, at the same time as the War with Mexico (1846–48). (They also occurred as the United States and Great Britain were settling their border dispute in the northwest; the Treaty of Oregon between the two powers was signed June 15, 1846, in Washington, DC.) In 1845, President Polk sought to take advantage of the American presence in California. He authorized John C. Frémont to lead a party on a topographical expedition into the Sierra Nevada mountains, the eastern border of California. It is not clear whether Frémont had other secret instructions from the President, but Polk’s Secretary of State, James Buchanan, sent a message to the American Consul in Monterey, California advising him to further America’s control in the territory by taking advantage of any unrest that might occur. (Monterey was the sometime capital of California and the official port of entry for goods.) Polk also secretly dispatched another American to California and ordered the Pacific squadron to the territory’s coast. In each case, the instructions were the same: be prepared to bring California under American control, especially if war with Mexico broke out.

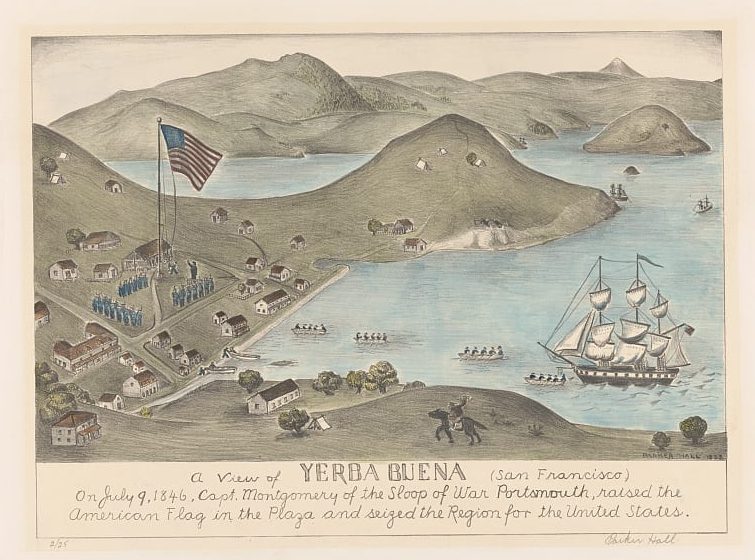

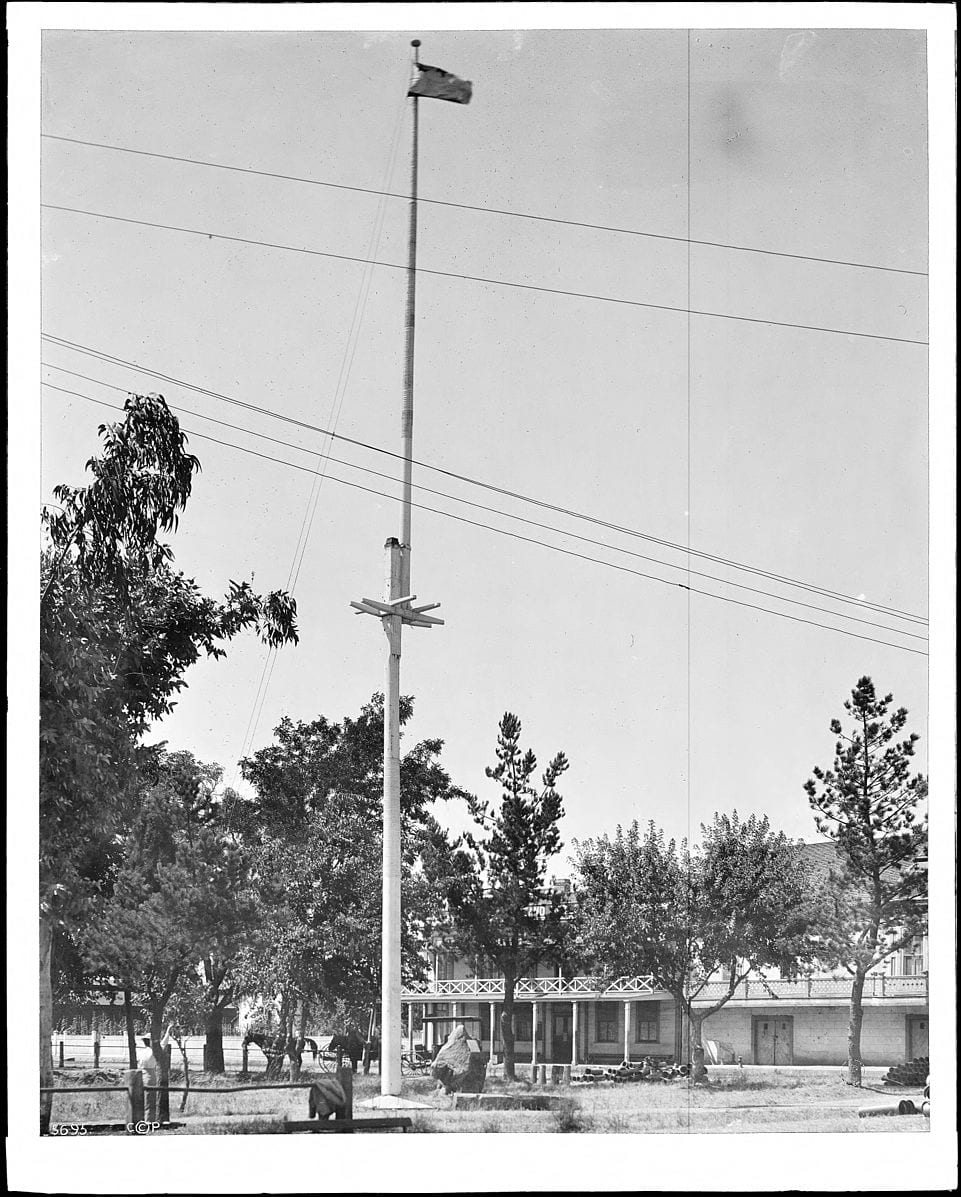

Whether or not instructed by Polk, Frémont played his part. He worked with various settlers, including the Bear Flag Republicans, to establish American control in the area near San Francisco. On June 16, he grandly declared himself military commander of U.S. forces in California. Meanwhile, a ship of the Pacific squadron under the command of John D. Sloat, hearing of fighting along the Rio Grande and the U.S. Navy’s blockade of Vera Cruz, headed for Monterey. On July 7, a large landing party quickly took control of Monterey and raised the American flag. On July 9, an American flag replaced the Bear Flag over the garrison north of San Francisco and the Bear Flag Republic came to an end. Frémont continued to work with Sloat and his replacement Commodore Robert Stockton, supporters of the former Bear Flag Republic, and others to extend American control. One after another, San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and San Francisco, where British warships lurked offshore monitoring events, fell to the Americans. Mexican forces and their allies among the Californios resisted, but by the end of August, Stockton was able to send a message to the Secretary of State that California was entirely under American authority.

In 1911, the State of California adopted the Bear Flag as its official state flag.