The Collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991

Thirty years ago the anticlimactic last meeting of the Supreme Soviet was held, marking the dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War.

In August 1991, opponents of Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to depose him. A coup led by the defense minister, the vice president, and the KGB chief detained Gorbachev and his family in their Crimean dacha. The state-controlled television network falsely reported that Gorbachev was ill and unable to fulfill his duties.

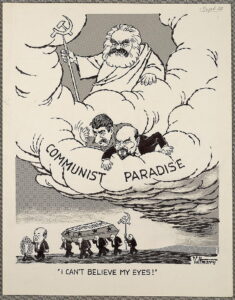

Gorbachev, who had come to power in 1985, had implemented ambitious reforms to fix an ailing nation. Malfeasance riddled the gargantuan Soviet bureaucracy. The setting of quotas burdened industry and agriculture. Inefficiencies in transportation, warehousing, and manufacturing bled millions of rubles from the economy every year. Chronic shortages of staples and consumer goods demoralized the population. Defense spending was unsustainable, but the Soviet Union remained mired in an expensive and increasingly unpopular war in Afghanistan. One of Gorbachev’s reforms, perestroika (restructuring), targeted corrupt and inept bureaucrats for removal; set up the Reform Commission, which eased centralized planning and permitted competition among state-owned industries; and reduced defense expenditures. By making the economy more efficient and profitable, Gorbachev wanted to prove to the Soviet people that communism could, in practice, meet their needs.

Another reform, glasnost (openness), tolerated limited criticism of the state as a gesture of transparency and accountability. The Party allowed historian Roy Medvedev to publish articles documenting the horrors of Stalin’s purges: approximately 20 million killed. By showing the population the Party and the state could admit its past mistakes, Gorbachev sought to gain popular support for his efforts. However, glasnost emboldened nationalities and minorities chafing under decades of repression to push for more autonomy, even independence. Veterans of the war in Afghanistan and their families began demanding accurate information about the status and costs of the war. Unintentionally, Gorbachev had enmeshed himself in a dilemma: the reforms he fervently hoped would save communism inspired the citizenry to demand changes that threatened the entire Soviet system. Hard-liners were just as determined to preserve communism without reforms, even if that meant carrying out a coup.

The coup quickly fell apart, however; its leaders had failed to solidify support within the military, giving the supporters of Gorbachev an opportunity to convince important officers to oppose his removal. Boris Yeltsin (president of Russia, the largest socialist republic within the Soviet Union) was the highest profile resister. Standing atop a tank in Moscow, Yeltsin urged the public to stand by Gorbachev. He also spoke to President George H.W. Bush on the telephone to inform him the coup was illegal.

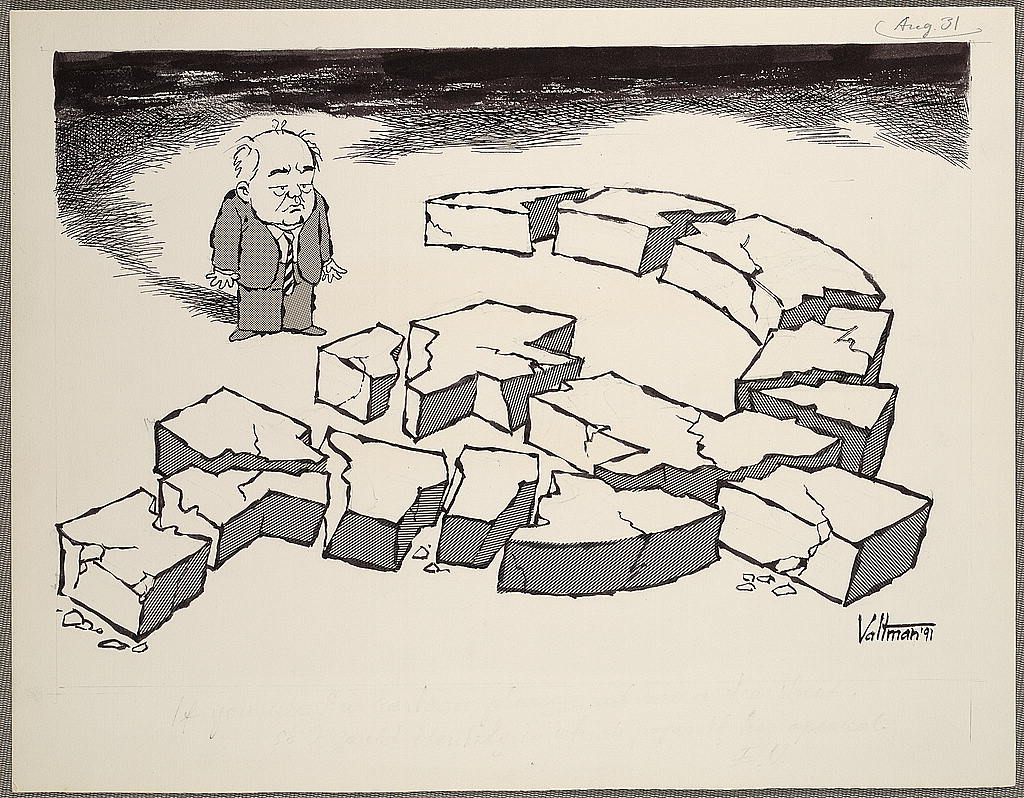

Within days, Gorbachev returned to power but not for long. Despite strenuous efforts to keep some semblance of the Soviet Union together, with him in charge, he could not halt the country’s dissolution. On August 23, Yeltsin outlawed the Communist Party in Russia. The next day, Gorbachev went one step further—he dissolved the Party in the rest of the country and resigned as its general secretary. The republic of Ukraine sped up its withdrawal from the union, following the example of the Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—which had left in the spring of 1990. On December 8, Russia and Belarus joined Ukraine in declaring that “the USSR as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality ceases its existence.” With no nation to lead, Gorbachev resigned on December 25, 1991.

The next day, the deputies of the Supreme Soviet met at the Kremlin. The Supreme Soviet was, on paper, the highest authority in the U.S.S.R., endowed with the power to enact laws and impeach the president. Its hundreds of deputies, split into two chambers, represented the Soviet people based on population (Soviet of the Union) and ethnic groups (Soviet of the Nationalities). In practice, the body was an imprimatur, obediently endorsing decisions already made by the Communist Party. At its final meeting, on December 26, 1991, the Supreme Soviet called itself into session to again rubber-stamp a fait accompli. Within its chamber, the Soviet flag had already been removed. Only a small number of deputies were present to approve a declaration belatedly recognizing the break-up of the Soviet Union and the disbanding of the Supreme Soviet itself. The declaration is notable mostly as irony: the national body that held so little real power was the last to speak for the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union’s rapid collapse was astonishing. Few leaders or experts predicted it. Certainly not Gorbachev, who had genuinely wanted to save the Soviet Union and communism from problems of its own making. U.S. national security experts also did not foresee—or advocate—the fall of the Soviet Union. In September 1989, the National Security Council offered guidance to President Bush on how the United States should respond to the remarkable changes occurring within the Soviet Union. Although it lauded perestroika and glasnost, National Security Directive 23 cautioned that the Soviet Union must also reduce its military forces and cooperate with the United States to reduce international drug trafficking, terrorism, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The main goal of U.S. policy should be the “integration of the Soviet Union into the existing international system” after decades in which the “Soviet Union has stood apart from the [international] order and often worked to undermine it.” The containment of communism, the pillar of U.S. foreign policy since the declaration of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, would be replaced by cooperation with a liberalized but still intact Soviet Union.

One leader who did predict the demise of the Soviet Union was Harry Truman. In his January 1953 farewell address, the outgoing president offered strikingly prescient observations. After reviewing the actions his administration took to halt the spread of Soviet power and of communism, Truman posed a question: “When and how will the cold war end?” Though the Communist world appears strong, “there is a fatal flaw in their society . . . the rulers’ fear of their own people.” To stay in power, communists rely on purges, secret police, and the suppression of religion. But their totalitarian ways cannot forever dim the light of freedom. So long as the U.S. and its allies remain strong and continue to block the spread of communism, “then there will have to come a time of change in the Soviet world. Nobody can say for sure when that is going to be, or exactly how it will come about, whether by revolution, or trouble in the satellite states, or by a change inside the Kremlin.”

Each of the possible scenarios Truman mentioned occurred. Together they brought the Soviet Union to its sudden end. Perestroika and glasnost represented change inside the Kremlin. Then, doubling down on his reforms, in 1988 Gorbachev repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine. Leonid Brezhnev had declared the doctrine after ordering Soviet forces into Czechoslovakia in 1968 to crush an incipient democratic revolution: the U.S.S.R. had the right to interfere with or invade other nations to protect communism. Gorbachev’s decision to abandon this imperial prerogative was, unavoidably, an admission that Marxism-Leninism was not infallible.

Numerous Warsaw Pact nations, bound to the Soviet Union in a collective defense pact, tested Gorbachev’s promise not to invade if communism was challenged. To use Truman’s phrasing, “trouble in the satellite states” quickly spread; and from that came revolution. The Solidarity labor movement in Poland, put down by force in 1981, resurged as a potent opposition party. In June 1989, Solidarity candidates won control of Poland’s legislature in free elections that would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier. The Soviet Union stood by, as it did when similar events transitioned Hungary and Czechoslovakia into representatively elected regimes with nascent market economies. The most dramatic change came on the night of November 9, 1989, when the beleaguered East German communist regime suddenly announced it would allow unobstructed passage through the Berlin Wall, including for East Germans wanting to go west. Just two years earlier, President Ronald Reagan, speaking with the Wall behind him, had thundered, “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” In an indirect way, Gorbachev did, by choosing not to act when Germans began pounding at the hated barrier that most vividly embodied the Iron Curtain.

In a telephone call to Bush just before he announced his resignation on December 25, 1991, Gorbachev offered an assurance that the transfer of his power to Boris Yeltsin (including the command of the former Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons) was proceeding smoothly. He also expressed his gratitude that he and the president had found common ground together as leaders. “As for me,” Gorbachev said, “I do not intend to hide in the taiga, in the woods. I will be active politically, in political life.”

That wish did not come true. The last leader of the Soviet Union quickly receded from political life, never again to hold a position of governmental power.

Bibliography

Svetlana Savranskaya and Thomas Blanton, eds., National Security Archive Briefing Book 576, “The End of the Soviet Union,” December 25, 2016. Available at: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2016-12-25/end-soviet-union-1991

Serhii Plokhy, The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

David Remnick, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire (New York: Random House, 1993).

William E. Watson, The Collapse of Communism in the Soviet Union (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998).