The Convention—and the Cause—that Organized the Confederacy

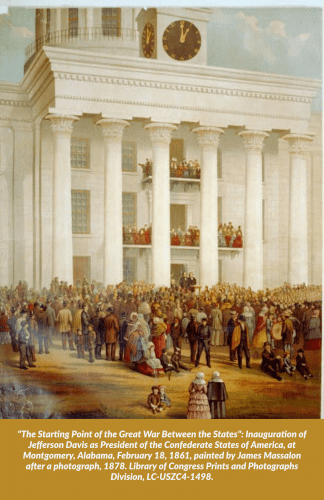

A critical step precipitating the Civil War was taken 160 years ago this month. On February 4, 1861, delegates from six states of the deep South convened in Montgomery, Alabama to organize a provisional government for what they conceived to be a new, independent republic—the Confederate States of America. Beginning on December 20, 1860 with South Carolina—and followed by Mississippi on January 9, Florida on January 10, Alabama on January 11, Georgia on January 19, and Louisiana on January 26—these states had declared their secession from the federal union. Texas, which seceded on February 1, would send its delegates to Montgomery a few days after the opening of the convention.

Montgomery, chosen for the convention because of its geographically central location, became the first capital of the Confederacy. The delegates began drafting a constitution closely modeled on that of the United States, yet unlike it in one key respect: it explicitly mentioned slavery and provided for the internal trade in slaves (while prohibiting their importation from other nations).

During the decades following the Civil War, Confederate apologists spilt a great deal of ink arguing that the Civil War arose because of federal threats to the rights of the Southern states to govern their own internal affairs. Secession declarations issued by four of the Confederate states make plain that the internal interest these states wished to protect from federal interference was slavery. For example, the secession declaration of South Carolina states that the original purposes of the American founding

. . . have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States . . . they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign [that is, remove] the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection. . . .

The secession declarations of Mississippi, Georgia and Texas are equally direct. [The declarations of Georgia and Texas can be found at “The Decision to Secede and Establish the Confederacy: A Selection of Primary Sources,” Teaching Resources for Historians, The American Historical Association.]

As these first seven of the Confederate states met in convention to form a new government, they knew they could not maintain their independence from the Union unless they persuaded other Southern states to join them. The Confederate convention’s decision to prohibit the importation of slaves from other nations was designed to persuade Virginia to secede. Virginia was not a large producer of cotton, but it supplied many of the slaves sold at auction to cotton-growers further south. The new Confederate Constitution assured Virginia that the income it derived from slavery would not be threatened.

Virginia voted to secede in April of 1861. In May, the Confederate Congress voted to move the capital to Richmond, Virginia. Doing so not only provided some relief from the heat and mosquitos of Alabama; it also located the Confederate seat of government in the most populous of the Southern states and the only one supplied with a plant (the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond) where heavy ordnance could be manufactured.

Virginia voted to secede in April of 1861. In May, the Confederate Congress voted to move the capital to Richmond, Virginia. Doing so not only provided some relief from the heat and mosquitos of Alabama; it also located the Confederate seat of government in the most populous of the Southern states and the only one supplied with a plant (the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond) where heavy ordnance could be manufactured.

In addition to the statements made in the secession declarations, other compelling evidence that the Civil War was fought entirely over slavery can be found in the letters and speeches of the secession “commissioners” sent out from the states that first seceded to those southern states hesitating to do so. (See, for example, the Letter of Stephen F. Hale to the Governor of Kentucky.) For his landmark study, Apostles of Disunion (University of Virginia Press, 2002 and 2017), historian Charles Dew located and analyzed these previously forgotten documents. He shows that the secession commissioners argued not only for the need to protect ownership of slave labor; they also warned against bloody slave insurrections likely to result from abolitionist interference in the South and, should slavery be abolished, revengeful attacks by the formerly enslaved on their former masters. They spoke as well of miscegenation and threats to Southern womanhood.

In the introduction to Apostles—a text often taught in our MAHG Core Course, Sectionalism and Civil War—Dew explains his own reversal of opinion about the cause of the Civil War. He grew up in Florida as a descendant of Confederates, firmly adhering to the “states rights” justification of the Confederacy. Hence, when he first encountered the letter of secession commissioner Stephen Hale to the Kentucky governor, he was stunned to find

. . . the same sentiments, the same views, indeed even some of the same ugly words, that I had heard used to justify racial segregation during my own youth. Could secession and racism be so intimately connected, I asked myself? I knew, of course, that the institution of slavery was on the line in 1860–61, but did white supremacy also form a critical element in the secessionist cause, a cause my ancestors fought for and that my relatives revered?

Dew concluded that the story the secession commissioners’ letters and speeches tell “is one that all of us . . . need to confront as we try to understand our past and move toward a future in which a fuller commitment to decency and racial justice will be part of our shared experience.” Several years ago I spoke by phone with Professor Dew, telling him about a joint project of five of our teacher partners, who arranged for their students to read Dew’s book and then talk via Webinar with Professor Dan Monroe about it. By then in his eighties, yet still teaching at Williams College, Dew was delighted to learn that his book had made its way into secondary school classrooms.