The Freedom Summer of 1964

For the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the trip north to Oxford, Ohio, from Mississippi in June 1964 was a welcome, even life-saving, respite. Leading voter registration efforts in Mississippi, these black men and women faced mortal hazards on a daily basis. Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper, had been jailed and beaten relentlessly with a blackjack. One young man had bullet scars in his neck. A white man had attacked Robert Moses with a knife as he escorted three people to a county courthouse to register.

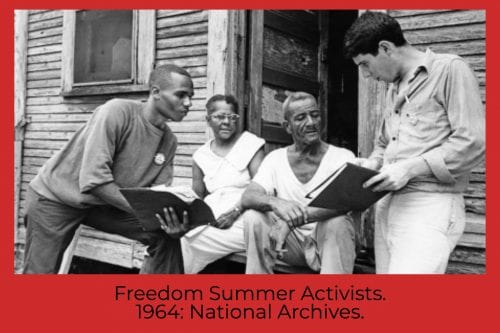

Oxford, once a station on the Underground Railroad, would again contribute to the freedom struggle. On a college campus, Hamer, Moses and other SNCC staff met hundreds of college-age men and women who had volunteered for the Freedom Summer, an ambitious voter registration effort concentrated in the Mississippi Delta, where just three percent of the black population (which was twice as large as the white population) could vote. One of the most important civil rights initiatives of the 1960s, the Freedom Summer brought a reckoning on racial injustice for Mississippi and the nation. Although the Freedom Summer did little to dislodge white supremacy in Mississippi in the short-term, the initiative helped build support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, put more pressure on the Democratic Party to confront its part in protecting white supremacy, and injected radicalism into SNCC. Above all, the Freedom Summer proved a biracial coalition could come to the Deep South and confront American racism in one of its strongholds.

For the Freedom Summer to succeed, SNCC needed help. White help. For four years, black civil rights activists in Mississippi had  been harassed, beaten, shot, and imprisoned; and blacks who helped them had been fired from their jobs, evicted, arrested, beaten, and killed. What for? Trying to exercise a right the Constitution entrusted Congress to protect. Yet for four years, the federal government had done almost nothing to protect SNCC workers and black Mississippians. The Kennedy administration appeared to hope Mississippi would find a way to enfranchise blacks without federal intervention; President Lyndon Johnson, determined to win passage of the Civil Rights Act in the summer of 1964, didn’t want SNCC or other civil rights organizations stirring up trouble, as he saw it. Moses and SNCC activists knew a surge of earnest white volunteers from middle and upper class backgrounds, a majority of whom attended elite universities, would attract national media attention that would follow them south, making it more difficult for the federal government to pretend nothing was happening. Moses made another calculation, a grim one: violence against privileged young white men and women was far more likely to bring federal protection than continued violence against African Americans. Such intervention might finally bring the necessary action to force Mississippi to recognize black voting rights.

been harassed, beaten, shot, and imprisoned; and blacks who helped them had been fired from their jobs, evicted, arrested, beaten, and killed. What for? Trying to exercise a right the Constitution entrusted Congress to protect. Yet for four years, the federal government had done almost nothing to protect SNCC workers and black Mississippians. The Kennedy administration appeared to hope Mississippi would find a way to enfranchise blacks without federal intervention; President Lyndon Johnson, determined to win passage of the Civil Rights Act in the summer of 1964, didn’t want SNCC or other civil rights organizations stirring up trouble, as he saw it. Moses and SNCC activists knew a surge of earnest white volunteers from middle and upper class backgrounds, a majority of whom attended elite universities, would attract national media attention that would follow them south, making it more difficult for the federal government to pretend nothing was happening. Moses made another calculation, a grim one: violence against privileged young white men and women was far more likely to bring federal protection than continued violence against African Americans. Such intervention might finally bring the necessary action to force Mississippi to recognize black voting rights.

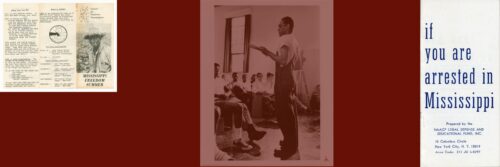

Not that SNCC wanted sacrificial lambs. As the volunteers poured into Oxford, SNCC carefully screened them. Glory-seekers were rejected; so too, anyone who seemed resistant to accepting instructions from an African American. Showing interest in interracial dating was an immediate disqualification. The volunteers learned the ABCs of safety, Mississippi-style. Never travel alone. Never stand in a doorway with a light behind you. Don’t dare tell a state trooper, sheriff’s deputy, or police officer you have “rights.” When the beating begins, drop to the ground and curl into a ball. On June 20, the first group of 300 volunteers boarded buses for the  journey south. One young man wrote to his mother, “Mississippi is going to be hell this summer. We are going into the very hard-core of segregation and White Supremacy . . . It is impossible for you to imagine what we are going in to, as it is for me now, but I’m beginning to see.” A Klansman in Mississippi agreed it would be a hot summer: “But the ‘heat’ will be applied to the race mixing trash by the decent people.”

journey south. One young man wrote to his mother, “Mississippi is going to be hell this summer. We are going into the very hard-core of segregation and White Supremacy . . . It is impossible for you to imagine what we are going in to, as it is for me now, but I’m beginning to see.” A Klansman in Mississippi agreed it would be a hot summer: “But the ‘heat’ will be applied to the race mixing trash by the decent people.”

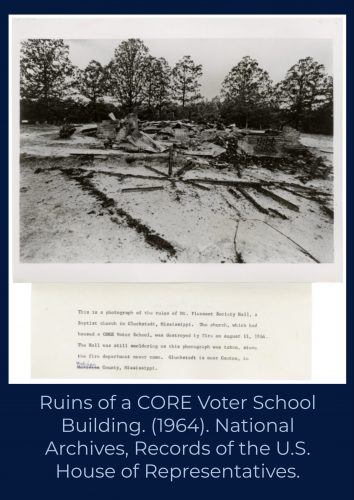

That threat of violence wasn’t idle. On June 21, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney went to Philadelphia, Mississippi, to investigate the bombing of a black church. They had strict instructions to leave town no later than 4 p.m. They never did. As anticipated, the fact that two of the missing men were white (Schwerner and Goodman; Chaney was black) prodded federal action. President Johnson ordered the FBI to investigate. Before the bodies of the three men were found in an earthen dam on August 4, searchers uncovered the bodies of several murdered blacks, victims of the anti-civil rights violence that had long raged in the state.

The murders cast a shadow over the Freedom Summer, as did continuing violence (almost 70 arsons and bombings) and arrests (1,000), but SNCC pressed on. More than 700 volunteers came to Mississippi. They helped set up forty-one Freedom Schools attended by more than 3,000 residents. The curriculum, supported by thousands of donated books, included mathematics, reading, and writing, also black history and the civil rights movement itself. The voter registration drives brought a record number of black residents to county courthouses: 17,000. Although only 1,600 succeeded in registering, both the schools and the registration efforts brought “moments of great interracial harmony,” as historian David Steigerwald has observed.

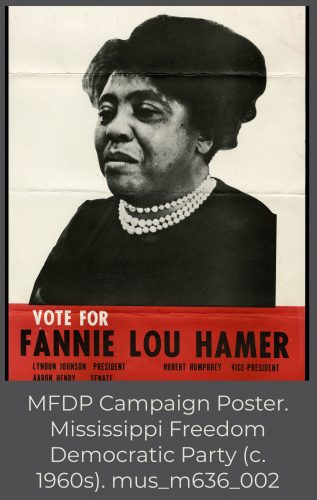

The Freedom Summer also led to the creation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). Moses led almost seventy  activists to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in August. Moses hoped to unseat Mississippi’s all-white delegation and replace it with residents who supported the national Democratic party’s platform on civil rights. Liberals in the party managed to get the MFDP an appearance before the Credentials Committee. Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech was broadcast on live television. An angry President Johnson dispatched Vice President Hubert Humphrey to strike a deal with the MFDP: they would get two at-large seats on the floor. They refused. A host of civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, urged the MFDP to accept the offer; still they said no. As Hamer put it, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats!”

activists to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in August. Moses hoped to unseat Mississippi’s all-white delegation and replace it with residents who supported the national Democratic party’s platform on civil rights. Liberals in the party managed to get the MFDP an appearance before the Credentials Committee. Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech was broadcast on live television. An angry President Johnson dispatched Vice President Hubert Humphrey to strike a deal with the MFDP: they would get two at-large seats on the floor. They refused. A host of civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, urged the MFDP to accept the offer; still they said no. As Hamer put it, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats!”

But the frustrations and setbacks masked positive outcomes. The voter registration drives drew national attention to Mississippi’s flagrant disregard of the Constitution. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 included specific provisions that demolished most of the methods used to turn away black voters. Ten years after passage of the law, Mississippi, of all southern states, had the greatest increase  in registered black voters. The Freedom Summer helped make that possible. Although Lyndon Johnson had scored a tactical victory over the MFDP at the 1964 Convention, the Democratic Party continued to evolve toward a firmer commitment to civil rights. This, too, the Freedom Summer helped make happen.

in registered black voters. The Freedom Summer helped make that possible. Although Lyndon Johnson had scored a tactical victory over the MFDP at the 1964 Convention, the Democratic Party continued to evolve toward a firmer commitment to civil rights. This, too, the Freedom Summer helped make happen.

Bibliography

Civil Rights Movement Archive, Civil Rights Movement Documents: Freedom Summer (Mississippi Summer Project), 1964-1965, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/msfsdocs.htm

Lytle, Mark Hamilton. America’s Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. Pp. 152-63.

Steigerwald, David. The Sixties and the End of Modern America. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995. Pp. 55-60.

Watson, Bruce. Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy. New York: Viking, 2010.