The Healthy-Bickering Brothers of Battle Creek

Each January, as the holiday parties end and the decorations are stored away, millions of Americans resolve to lose weight, eat healthier, and exercise more vigorously. If this is your plan for 2021, you are not alone. According to one poll, nearly half of all Americans resolve to embrace a healthier lifestyle in the new year. However, few of them will contemplate including a large bowl of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes in their wellness regimen. Yet, as a nutritious grain-based alternative to a breakfast of bacon and eggs, the development of Corn Flakes was the dream of John Harvey Kellogg and his intrepid brother Will and an integral part of an early 20th-century wellness movement known as “biologic living.”

John Harvey Kellogg, the older, more scientifically minded of the two brothers, was a man ahead of his time. John’s prescriptions for a healthy lifestyle would be as welcome on today’s health-oriented websites as they were at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, the medical center he built to promote his vision. Known as Dr. Kellogg, John urged his devoted followers to stop consuming sugar, caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and meat. He viewed obesity as a health hazard and encouraged his patients to get sufficient sleep, reduce stress and cultivate a worry-free attitude. He even invented an ergonomic chair long before the term ergonomics became commonplace. Overall, Dr. Kellogg sought to prevent disease by combining a diet of grains and vegetables with vigorous exercise or physical activity, a strict regimen that few Americans embrace today despite its support from modern health enthusiasts.

Though the brothers bickered like schoolboys their entire lives, they began their careers collaborating on a health and fitness resort in their hometown of Battle Creek, Michigan. Their father, John Preston Kellogg, was a devout follower of Seventh Day Adventism, a denomination that promoted healthy living. In 1876, he offered financial backing of the Adventist Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek, on the condition that the Adventist Elders name his son John medical director. Four years later, Dr. Kellogg hired his brother Will to be his assistant. After fire destroyed the original “San” as it was called by its patrons, the brothers build a larger hospital, wellness center and nursing school. They also published Good Health magazine, which featured self-help articles frequently penned by Dr Kellogg himself.

The “San” successfully marketed its health philosophy to wealthy and influential figures. Politicians—including presidents Taft, Coolidge and Hoover—visited the San. So did celebrities Johnny Weissmuller and Eddie Cantor. Business titans—Harvey Firestone, J.C. Penny and Henry Ford—became frequent summer visitors. Unfortunately, as Dr. Kellogg’s methods began to be embraced by the rich and powerful, making him famous, his penchant for bullying his younger sibling also grew. Twelve years after the brothers perfected their formula for Corn Flakes, Will could take the abuse no longer. He offered to purchase his brother’s interest in the company. More interested in science than business, Dr. Kellogg quickly agreed to sell his interest. Later, regretting this decision, John Kellogg sued his brother for patent infringement. Following a ten-year legal battle, Will was declared the rightful owner.

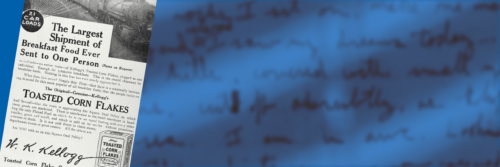

Will Kellogg’s talents as a businessman equaled John’s scientific skills. According to medical historian Howard Markel (author of The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek), Will became “a major player in an entirely new industry centered on the transformation of foods from their natural state into cooked, shaped, chemically manipulated, mass-manufactured products” by doggedly pursuing the latest efficiency techniques and business systems. His timing was impeccable. Kellogg’s Corn Flakes benefited from America’s rapid urbanization, industrialization, and the availability of safe pasteurized milk, the cereal’s vital companion. Yet the company owed its success to Will’s marketing expertise. Will maximized new mass marketing techniques, including radio ads flavored with catchy jingles and prizes stashed in the cereal boxes. He calculated the prize’s cost and the amount of cereal that the prize would replace, finding that the cost of the prize was less than the cost of the displaced cereal. This ingenious marketing appeal to children increased his profits

Today, the cereal industry is attacked for its emphasis on sugar. Some critics argue that the industry has contributed to the obesity epidemic in children. However, the brothers stayed true to their focus on a convenient healthy cereal while they lived. In addition to Corn Flakes, the company developed All Bran and Rice Krispies in the same vein. It was only after Will’s death in 1951 that Kelloggs began adding large amounts of sugar to its cereals.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s legacy suffers for another reason. He was always receptive to the latest scientific fad. Enthralled by a vision of “race betterment,” Dr. Kellogg joined other early twentieth century progressives in an enthusiasm for the eugenics. Even after World War II, when revelations of Nazi eugenic experiments discredited the movement, Dr. Kellogg continued to promote it.

The Kelloggs’ sibling rivalry, as described in Markel’s book and fictionalized by T.C. Boyle in The Road to Wellville, is tragic. It took both brothers’ expertise – John Harvey’s scientific curiosity and creativity and Will’s organizational and business acumen – to create the Kelloggs’ economic empire. Yet their collaboration turned into a bitter rivalry that remained unresolved until their deaths as nonagenarians. Despite their contributions to bodily health, they left behind them a cautionary example of poisonous family psychology.