The Importance of Gettysburg

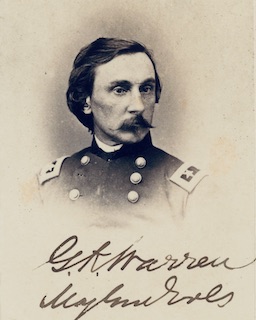

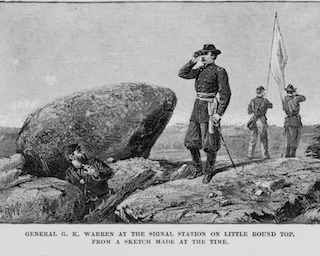

General Gouverneur K. Warren saw the problem in a flash, the flash of Confederate bayonets threatening the Army of the Potomac’s position on Cemetery Ridge near the village of Gettysburg. Behind Warren was Little Round Top, a rocky outcrop that the army’s commander George G. Meade had ordered troops to use as an anchor for the Union’s defensive position. To Warren’s surprise, the only Union troops occupying Little Round Top at 3:00 PM on July 2, 1863, were a small signal corps. As Meade’s chief engineer, part of Warren’s job was identifying weaknesses in the Union lines. What Warren saw was not just a weakness but an impending disaster. If the Confederates captured Little Round Top, they could direct artillery fire along the length of the Union line. The Battle of Gettysburg, the success of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the North, and possibly the war’s outcome hung in the balance.

Contemporary accounts of what happened next differ, but none question Warren’s vital role at this critical moment in the three-day battle of Gettysburg. Though he commanded no troops of his own, he persuaded two Union officers to cooperate. First, Colonel Strong Vincent agreed to lead his men to the top of Little Round Top. They arrived at the crest of the hill just 15 minutes before the Confederate assault. They repulsed several charges. Next, Warren secured artillery support, then went back down the slope seeking reinforcements. He found them in his former regiment, the 140th New York, commanded by Colonel Patrick O’Rourke. O’Rourke protested Warren’s authority to take his troops up the rocky slope, telling Warren he had different orders. Warren told O’Rourke that he would bear responsibility. O’Rourke had learned to trust Warren’s judgment when he served under him in the 140th, so he led his troops up and over the top into a full assault on the oncoming rebels.

I first heard the story of General Warren’s heroics in 2013 when my son Ben and I attended the 150th-anniversary activities hosted by the National Military Park in Gettysburg. It was a last-minute decision for us. So many people came to Gettysburg that year that the only hotel we could find was an hour away. On July 2nd we listened as a Park Ranger described General Warren’s actions 150 years earlier. I remember the look on his face when he told the tale. Shaking his head in disbelief, he said, “You just can’t make this stuff up.” I wondered why the Battle of Gettysburg fascinates so many Americans. Why do so many Americans flock to Gettysburg each summer to commemorate a battle that caused so much death and destruction? Was it just because of the sub-plots in the battle that seemed stranger than fiction?

These questions continued to haunt me the next day. Ben and I joined reenactors on Seminary Ridge that afternoon preparing to recreate Pickett’s Charge, the infamous climax of the battle. I asked a Park Ranger standing nearby if he knew how the number of re-enactors—both those in uniform and those who were not—compared to the number of soldiers in Pickett’s Charge. He told me that the rangers had been discussing that question throughout the afternoon. Though they did not have an exact number, the consensus was that the re-enactors doubled or tripled the number of Pickett’s’ soldiers.

One answer for the pilgrimages to Gettysburg is suggested by the Civil War historian James McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom, the best one-volume account of the war. McPherson argues that “the Union won the war mainly by victories in the West, but the Confederacy came close to winning it in the East.” Many Americans are fascinated by how close the Confederacy came to winning the war in that small Pennsylvania crossroads.

The battle of Gettysburg raises numerous what ifs. What if John Buford’s Union cavalry had not purchased with blood a few precious hours, allowing Meade’s army to reach Gettysburg July 1, 1863? What if Stonewall Jackson had not died from wounds he received at Chancellorsville two months earlier? Would Jackson’s presence have been decisive? What if the bombardment of Confederate lines preceding Pickett’s Charge had disabled Union cannons?

Perhaps the biggest what if of the battle involves General Robert E. Lee. What if Lee had taken the advice of Lieutenant General James Longstreet and attempted to flank the Union lines to the south and east? Could he have placed his army between Meade’s and Washington, just over 80 miles away? If that happened, would the ensuing panic have caused President Abraham Lincoln to negotiate with the Confederacy? Would it have led to foreign recognition of the Confederacy by France or Great Britain? Lee repeatedly rejected Longstreet’s advice saying, “The enemy is here, and I am going to strike him here.” To Lee, his men had proven they could achieve anything he asked them to do. At Gettysburg, he asked them to do more than any army of the day could accomplish.

Military historians see Gettysburg as the turning point of the war. Though it dragged on for two more years, Lee’s army never again invaded the North. Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant Commanding General of the United States Army and the rebellion became a war of attrition. A war impossible for the Confederacy to win.

No one can predict what the United States would look like today if the seceding states had won their independence. But we know it would have delayed indefinitely the emancipation of four million souls trapped in bondage in the 1860s. Enslaved people would have continued to escape north to freedom. Tensions between the United States and the Confederate States would have remained high—future wars inevitable. Thankfully, that did not happen. The Union triumphed at Gettysburg and in the larger struggle.

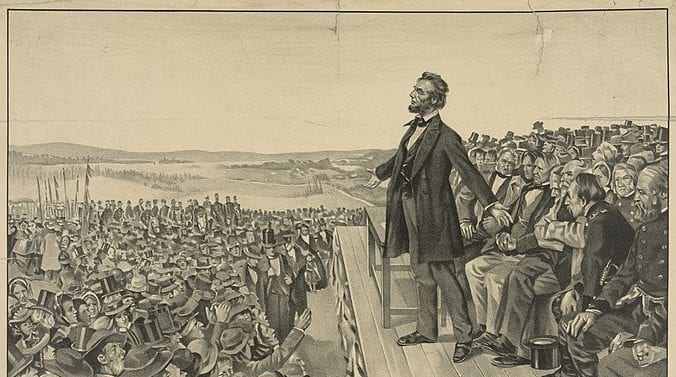

Gettysburg’s legacy is not only the battle’s military outcome. It includes the vision of America articulated by President Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address. It is a myth that Lincoln wrote the speech on the back of an envelope as he traveled to Gettysburg. Although he was not the ceremony’s featured speaker—that honor went to Edward Everett—Lincoln was not going to arrive unprepared. Indeed, he began developing the theme of his famous speech on July 7th, when a crowd celebrating news of the Union victory gathered at the White House calling for the President to speak. “How long ago is it—eighty odd years,” the president said, “since on the Fourth of July for the first time in the history of the world a nation … declared as a self-evident truth that ‘all men are created equal.’” Lincoln acknowledged the crowd’s reason for celebrating. The victory called “for a speech, but I am not prepared to make one worthy of the occasion.” In Gettysburg, eighty odd years became “four score and seven” and the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” became a proposition undergoing its greatest test.

By November of that year, he was fully prepared. The Emancipation Proclamation was nearly a year old. African American men were answering the call to join the battle for freedom and Union, leading Lincoln to admonish his friend James C. Conkling that August, “You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union.” The victory at Gettysburg was accompanied by a similar triumph in the West when Grant’s siege of Vicksburg succeeded. “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea… Peace does not appear so distant …” Lincoln told Conkling. The war was no longer only about saving the Union. It was about the principle of equality for all. For the dead at Gettysburg not to have died in vain there must be “a new birth of freedom,” a breaking of the chains of chattel slavery.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.