The Journey and Meaning of the King Holiday

As we recognize the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday this January 17, it’s worth reflecting on the road to a national commemoration of our most famous civil rights leader. The momentum toward a federal King holiday began almost immediately after King’s assassination, with Representative (and civil rights activist) John Conyers first proposing a federal holiday within a week of King’s death in 1968. Thereafter, congressional proposals for a King holiday became an annual occurrence. But fifteen years would pass before the holiday won federal recognition in 1983, eighteen years before the first federal celebration in 1986, and 32 years before all 50 states observed it in 2000. In addition to the political work in D.C. to achieve this goal, an advocacy campaign was waged on social, cultural, and economic fronts. A brief account of the holiday’s journey from vision to national practice tells us much about the nation’s journey in its understanding of King and the broader civil rights movement.

Local governments initially established public symbols honoring King, particularly in communities where black citizens held significant political and social influence. The city of Detroit (Representative Conyers’ hometown) renamed a public high school for King in the fall of 1968, and the early 1970s saw a boom in renaming and establishing schools in King’s honor, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast. Community activists sought to rename streets in King’s name. The first street renaming was in Chicago (1968), initiating this trend. Today one finds MLK schools and streets throughout the nation, but in the decade following King’s death, these public commemorations were an important plank in the movement, aiding political petitions for a holiday.

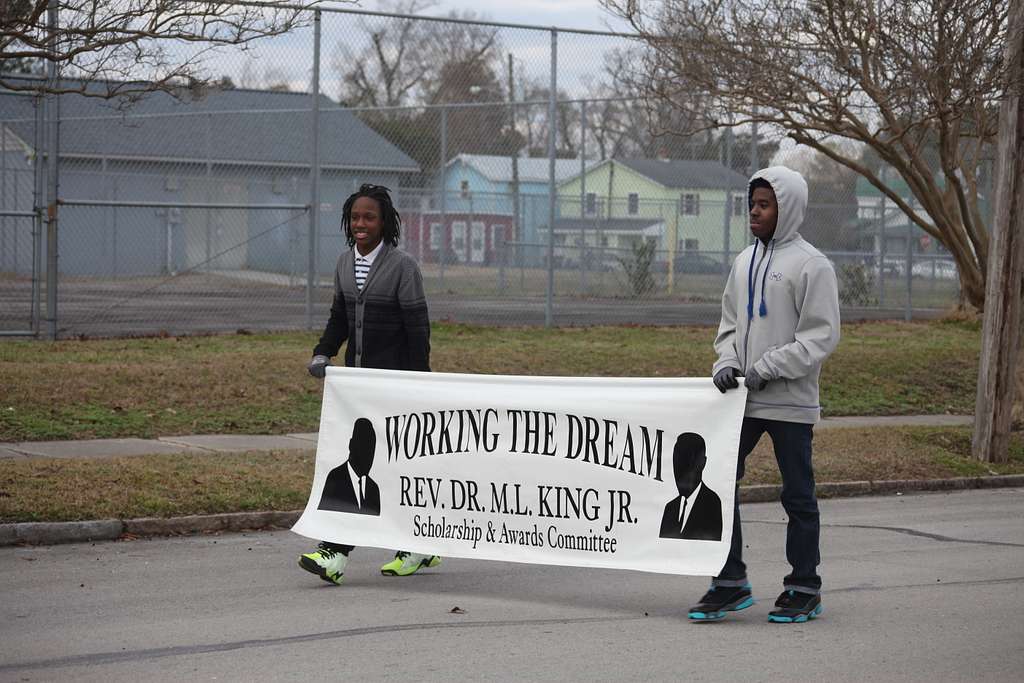

These public symbols partnered with a grassroots citizens’ lobby for the holiday. Public observances of the holiday began on the local level, starting with a 1969 observance by the year-old King Memorial Center in Atlanta. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and National Council of Churches both petitioned Congress to pass a King Holiday in the 1970s — with signatory support in the millions. The American labor movement, having found an ally in King during the mid-60s, also promoted the holiday throughout the 1970s. Picking up the momentum, state governments began enacting the holiday: Illinois in 1973, followed by Massachusetts and Connecticut in ‘74, and New Jersey in ‘75. By the time of the first federal observance, seventeen states already had King holidays.

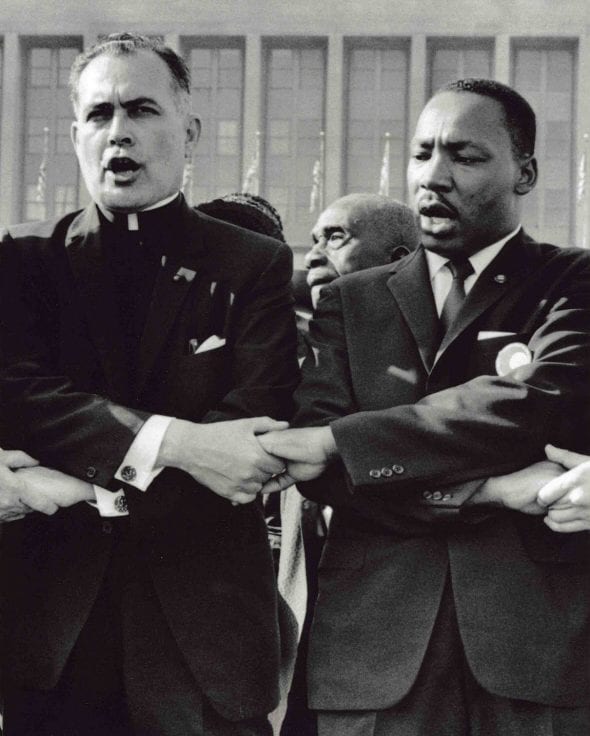

Grassroots efforts and support slowly impacted the more sluggish federal response. Eleven years after King’s death the federal King holiday finally received a vote on the floor of the US House of Representatives. While the bill fell five votes short of its required two-thirds House supermajority for passage as a “special procedures” bill, it was an important political turning point. In the eleven years since his death, King’s legacy had become anchored in public spaces, and grassroots work was yielding political fruit. Advocacy took another step forward with Stevie Wonder’s 1980 song “Happy Birthday” from the album Hotter than July, which managed to be a huge success and became the musical anthem of the holiday push without ever being released as a single in the United States. Its success as an international single, however, helped draw global attention to the effort. From this point, Wonder became a regular presence in the King holiday movement, often advocating alongside Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King. The efforts of activists, a celebrities, and politicians coalesced by the turn of the 1980s, creating a groundswell for the holiday.

Perhaps surprisingly, the effort to elevate the King holiday–combined with the effect of historical detachment–won much of the public over to the civil rights cause, making it more popular in hindsight than it was in its own time. My students, the oldest of whom were born nearly twenty years after the first federal King holiday, are surprised to see historical numbers on civil rights support: Gallup polling indicating public opposition to the March on Washington in 1963, as well as to other nonviolent demonstrations like sit-ins; or a 1964 New York Times article reporting skepticism among white New Yorkers of civil rights efforts; or that King’s public approval rating had fallen into the 30’s by 1966, when he began advocating more fervently against economic injustice and housing discrimination. It seems impossible to them that a historical figure with a holiday named after him could ever have faced such opposition from so many Americans, or that the civil rights movement did not enjoy the near-universal approval popular culture today would seem to indicate.

Yet in fact, Senator Jesse Helms, leading congressional opposition to the King holiday, threatened to filibuster the 1983 legislation while resurrecting accusations that King was a Communist sympathizer (like a number of other civil rights activists, King faced charges of communism throughout his career, despite his disavowals in sermons like 1962’s “Can A Christian Be A Communist?” and speeches like 1967’s “Where Do We Go From Here?”). Nonetheless, the King holiday movement had won sufficient public and political support to pass. President Reagan signed the bill into law in 1983, with the first federal holiday scheduled, and observed, in 1986.

From Federal to National Holiday

But in American federalism, a federal holiday does not make an occasion a national holiday. In a decentralized system with 50 state governments, holiday mandates do not fall within federal power. In the case of the MLK holiday, the federal example and the energy placed behind it (in the form of the King Holiday Commission, established in 1984) promoted a nationwide wave of state recognition, so that 44 states recognized the holiday by the turn of the 90s.

Even then, states often titled the holiday in ways that softened the focus on King, remnants of discomfort with — if not outright antipathy to — the civil rights leader. An early example was appending “Human Rights Day” to the holiday (as in Idaho & Utah). The early 90s offered the most memorable example of resistance to the King Holiday, from Arizona, where, after a state referendum rejected the King Holiday in 1990, protest and boycott campaigns eventually influenced the National Football League to apply economic pressure by moving Super Bowl XXVII (1993) from Arizona to California — the first major relocation of an American sporting event for political reasons.

But Arizona was not the last state to adopt the King Holiday; that distinction belongs to New Hampshire and South Carolina, who became the 49th and 50th states to observe it in 2000. New Hampshire merged a more ceremonial “Civil Rights Day” with the King Holiday; South Carolina ended a practice of allowing state workers and localities to choose among the King Holiday or one of three different Confederate holidays — a practice seemingly subversive to the purpose and intent of the King Holiday, but which had been mirrored in four other former Confederate states where King’s holiday was merged with celebrations of General Robert E. Lee (and in the case of Virginia, also Stonewall Jackson). The King Holiday’s passage through the federal system underscored the contested nature of King’s legacy, and by extension the movement, decades after his passing.

The Real Meaning of the Holiday

At the time of its passage, the King holiday was the third federal holiday identified with an individual, after George Washington’s Birthday and Columbus Day. The two previous holidays were understood as celebrating the achievements and accomplishments of particular individuals (and in the spirit of federalism, are also recognized by other names in some parts of the country: Washington’s Birthday is commonly broadened to Presidents Day, and communities critical of the Columbus holiday observe Indigenous People’s Day — indeed, a majority of states no longer refer to the October holiday as Columbus Day).

But the King Holiday, while commemorating an individual, was also framed from the outset as dedicating the nation to the work for which he lived and died. Rather than understanding it as a civil rights “mission accomplished” celebration, the King Center has always framed the holiday as a commitment to carrying forward the unfinished work of Dr. King. Similarly, at the time of congressional passage in 1983, TIME magazine reporter George Church noted that the holiday “symbolize[d] the commitment of all Americans to racial equality” — active rather than passive observance. Subsequent expansions of the holiday’s observance maintain this mode — as in the 1990s shift to framing the holiday as a broader “day of service.”

Seeing the King Holiday as an active national engagement allows us to elevate underappreciated passages from King’s great body of work. The more detached “celebratory” mode of engagement with King’s work — as a done deal, a feat accomplished, or mostly accomplished — tends to limit historical memory to a handful of exalted quotes. While these passages are powerful and essential to understanding Martin Luther King, focusing on them tends to reduce and distort public understanding (and the way we teach King’s message to students). These discussions emphasize the inspirational and aspirational closures of King’s speeches, especially the inspirational flourish at the close of King’s March on Washington speech, “I Have A Dream.” Another popular quote is King’s oft-used assertion that the “arc of the moral universe … bends toward justice.”

And yet in these speeches and so many others, you find King challenging the nation with a brand of critical patriotism, harkening back to foundational principles while simultaneously seeking “to dramatize a shameful condition” of social injustice. This is the King who celebrated the Founding Documents and Abraham Lincoln while highlighting contemporary conditions as a “default … on this promissory note” in “I Have a Dream;” who excoriated Jim Crow as “a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition;” who exalted the Bill of Rights and the “greatness of America” while demanding that the nation “be true to what [it] said on paper;” who critiqued the nation’s “Schizophrenic personality on the question of race;” which created disparities between democratic principles and practices. King felt that the nation’s first principles demanded this tough critical engagement with current injustice–that pursuing both civil rights and social justice was essential practice in the “more perfect union.” A responsible holiday in his name must reckon with this advocacy as well.

Finally, while King repeatedly spoke of the moral arc bending toward justice, he also constantly reinforced what he referred to as “the fierce urgency of now,” insisting that “human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability, it comes through the tireless efforts and the persistent work of dedicated individuals [against] the primitive forces of social stagnation.” Just as generations of citizens worked to establish the King Holiday, may we celebrate it today as an ongoing, unfinished mission.

Malik Ali, a 2017 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, is Tukman Distinguished Teacher of History at the Branson School in Ross, California.

Additional Sources

Alderman, Derek. “School Names as Cultural Arenas: The Naming of U.S. Public Schools after Martin Luther King, Jr.” Urban Geography, Vol. 23 (November 2002).

Alderman, Derek. “Street names and the scaling of memory: The politics of commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr within the African American community.” Area, Vol. 35 (June 2003)

Chandler, Stacy. “Making the March on Washington, August 28, 1963.” JFK Library Blog. August 27, 2020.

Church, George. “A National Holiday for King.” TIME Magazine. October 31, 1983.

The King Center Online: https://thekingcenter.org/

Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/search.

National Constitution Center. “How the Martin Luther King Jr. birthday became a holiday.” Constitution Daily. January 16, 2021.

United Press International. “Dr. King Holiday Bill Fails to Win in House.” via The New York Times, November 14, 1979.

Weinfuss, Josh. “Looking back at the NFL moving the Super Bowl from Arizona due to Martin Luther King Jr. holiday.” ESPN. July 12, 2021.