The Long Road Toward Civil Rights

Talking with Peter Myers, editor of Race and Civil Rights

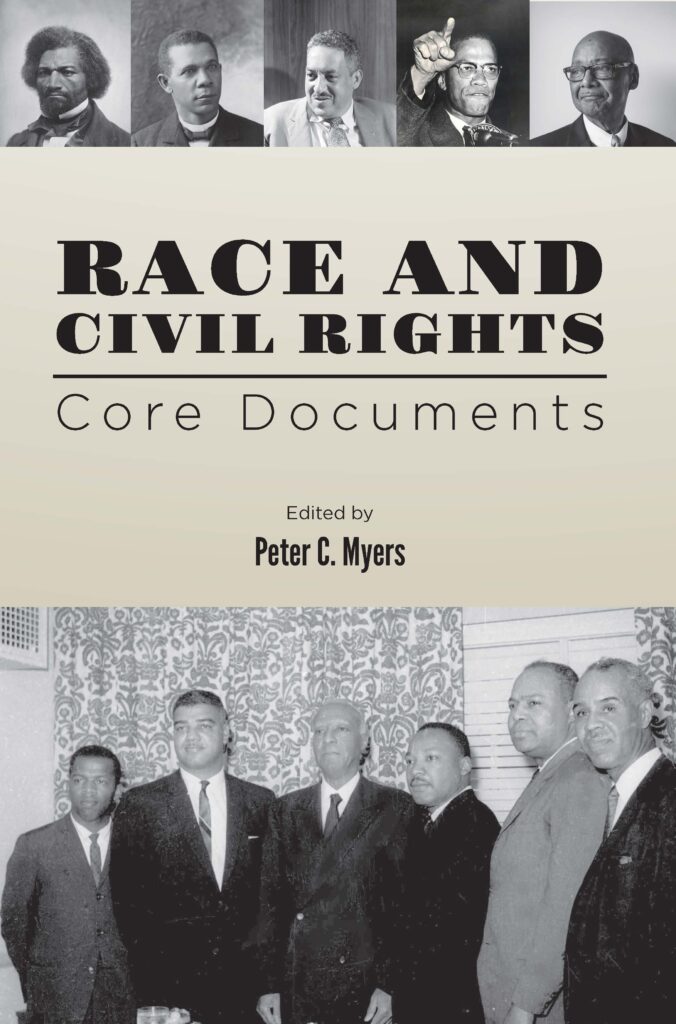

This month we released a new volume in our Core Document Collection, Race and Civil Rights, edited by Peter C. Myers. The volume covers the long struggle to secure legal, political and social equality for black and white citizens, a struggle that began the moment slavery was abolished. As Myers writes, the documents he selected address the question of “whether and how” black and white Americans can “come to coexist and thrive as fellow citizens.”

Myers is a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, where he teaches political philosophy, American political thought, and Constitutional law. As a visiting professor in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, Myers has taught courses on Race and Equality, the Civil Rights Era, Tocqueville, Martin Luther King, Abraham Lincoln, and Frederick Douglass. In 2008 he published Frederick Douglass: Race and the Rebirth of American Liberalism (University Press of Kansas).

We asked Professor Myers to talk with us about the collection.

1. Much has been written on race and civil rights in America. How did you decide which selections to include?

It wasn’t easy! Given the Ashbrook focus on primary sources, I chose to focus on authors involved in activism—officeholders, leaders of activist organizations—and on court cases. That meant excluding a world of literary authors like Ellison, Baldwin, Zora Neal Hurston, and others who’ve influenced our thinking on race relations. But it put the focus on practical efforts to bring change.

I hoped to show the diversity of approaches to justice in race relations. I tried to include authors rarely celebrated today. For example, Robert Brown Elliot represents African Americans elected to Congress during Reconstruction; his speech to the House (1874) critiquing Alexander Stephens will interest teachers who use Stephens’ Cornerstone Address to convey what the Confederacy stood for. Albion Tourgée, who migrated to the South after the Civil War to try to help steer Reconstruction, played an important role. He argued for the plaintiffs in Plessy, originating the term Justice Harlan uses when arguing that the Constitution is “colorblind.” The educator Anna Julia Cooper emphasizes the key role of women in “A Voice from the South” (1892).

Many students are unaware of Civil Rights efforts prior to those of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference under Martin Luther King. I wanted to show the movement’s long duration. Because of permissions costs, we could not reprint King’s writings, yet we included some who developed strategies King later used. A. Philip Randolph’s call for a March on Washington in 1941 laid the groundwork for the 1963 March. Bayard Rustin describes the strategy of nonviolent resistance in his account of being arrested in 1942 for refusing to ride in the back of the bus. Rustin became one of King’s closest advisors.

Finally, I wanted to represent the current debate over what remains to be done to overcome racial injustice. Which voices would be relevant twenty years from now? Nicole Hannah Jones’ lead essay for the 1619 Project seemed a good bet, as it is backed by The New York Times. The Black Lives Matter movement is well known and funded, so we excerpted from its founders’ statements of purpose. We also included Robert Woodson’s introductory essay to the “1776 Unites” campaign. Woodson will be unfamiliar to many readers, but he has worked for years to promote enterprise and improve outcomes for young people in disadvantaged communities. He’s one of the unsung heroes of our day.

2. Race and Civil Rights documents disagreements among African Americans on how best to pursue civil rights. Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois famously disagreed on whether African Americans needed industrial training or higher education. Was this simply a disagreement about strategy?

It was both more and less than that. In TAH seminars, we read the Atlanta Exposition Address alongside Du Bois’ chapter on Washington in The Souls of Black Folk. I ask, “Does Washington really think that blacks should not pursue liberal education?” Teachers respond, “No, he thinks they should.” When I ask whether Du Bois opposes industrial education for working class blacks, teachers respond, “Well, no.” Some scholars describe the disagreement as a rivalry, noting that Du Bois resented Washington’s control over a great deal of northern philanthropy money. Still, the two fundamentally disagreed about the value of political agitation. Washington thought too much protest becomes undignified. If the effort fails, people conclude they are powerless. Du Bois—like Frederick Douglass—thought people gained dignity and self-respect in standing up for their rights, whether they prevailed or not.

Du Bois wanted to tear down an unjust system. Washington thought that the post-Reconstruction era called for construction, not destruction: for building up new institutions. After all, he was not just training people to be better farmers; he was training professionals—people who would become teachers in the black community. He pushed for reform privately, bargaining through back channels for his community. He worked in much more difficult circumstances than Du Bois ever did—a fact that, later in life, Du Bois acknowledged.

You might say Washington and Du Bois developed the opposite poles of what, for Frederick Douglass, was a unified strategy. Du Bois emphasized protest; Washington emphasized self-improvement.

3. Do these approaches reunite in Ida B. Wells? While protesting lynching, Wells exhorts Black Americans to use their economic power. She says, “To Northern capital and Afro-American labor the South owes its rehabilitation.”

Wells makes an interesting argument in her essay “Self-Help,” pointing out that self-help entails not only self-improvement but also self-defense. She cites an unpunished lynching in Memphis that caused many black citizens to leave the city and others to boycott the streetcars. This brought about “great stagnation in every branch of business” in Memphis. Wells, like Douglass and Malcolm X, also urges black families to buy guns and use them “for that protection which the law refuses to give.” A realist, Wells sees people responding to fear sooner than to love.

In less confrontational terms, this is really Washington’s argument. You can read two messages in his “Atlanta Exposition Address.” When he says, “Cast down your buckets where you are,” he’s telling white employers that they don’t need to hire immigrant labor; the Black population will supply the labor needed. But he is also alluding to the decision of some African Americans to leave the South. The threat of leaving was the one economic lever the Black population had.

4. A tension between the integrationist and separatist impulses pervades the collection. Some authors assert their respect for American ideals and their hope to gain civil rights and prosper in mainstream society. Others want to build separate communities and nurture a separate identity. One might expect greater enthusiasm for integration following passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s. Why, at that moment, does the Black Panther Party emerge, along with the publication of Black Power by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton?

It’s a complicated thing. I would note that the integrationists have always comprised the much larger number of Black Americans. And separationists come in different gradations and modes.

Yet it’s predictable that, after so long a history of organized societal disrespect for a group of people, they would publicly assert their pride in their cultural identity—while claiming a right to public respect.

Some see Black separatism as self-defensive. You can question the tone of Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s report on a crisis in the Black family, but not his prediction that the enactment of civil rights laws would not solve our race problem. Once equal treatment under law is established, socio-economic inequalities appear more glaring. Some explanation will be demanded, and the explanation will offend somebody. It’s not hard to see how the question would arise, and would also inflame many people’s sensitivities: “Now that you have equal treatment and equal opportunity under law, why aren’t you achieving more?” Among the possible responses is a line of argument initiated by Black Power advocates: “Your standards of merit are not universal; they’re culturally specific.” This gives impetus to the identity politics that we’ve lapsed into in the post-Civil Rights Era.

Historical memory is perhaps the most important factor, also emphasized in the Black Power argument. Black people do not forget that they have been treated as a people apart. They sustained themselves by cultivating a sense of their distinct identity.

5. Some themes emerge in the documents that one might explore in a longer collection. For example, Albion Tourgée, writing during Reconstruction, speaks of the common ignorance and poverty of most whites and blacks in the South. He sees Jim Crow policies as designed to serve the interests of an educated Southern oligarchy. Other documents allude to problems in our criminal justice system.

Tourgée was fiercely anti-oligarchic. When he advocates a greatly expanded system of public education, he makes plain his view that both blacks and whites have suffered under a racialized oligarchy. He wants to lift the working classes of both races. He’s also hard on northern Republicans in their approach to Reconstruction. He felt the South needed much more help in building a democratic culture than it got after the Civil War.

The problems with our criminal justice system have been much discussed recently, and they are long-standing. The Black Lives Matter statement mentions them in a tendentious way, yet it’s undeniable that for a long time, the system was overtly organized against blacks. Current police encounters are interpreted in light of that history. It would take a much longer volume to represent the range of perspectives on this.

Another theme is the role of religion in the struggle for civil rights. A longer collection might include Washington’s speech “Democracy and Education,” in which he makes very clear that his idea of education is not industrial education. It’s moral education, and it’s Christian moral education. Douglass also often spoke in terms of Biblical morality. Malcolm X brings a religious perspective to the fight for racial justice, and certainly Bayard Rustin does. I included a selection from the Reverend Joseph Jackson because he worked in the same religious tradition as King, yet reached very different conclusions. Even more than King, Jackson wanted to find resources in the existing American tradition to advance the cause of equal rights under law.

6. What important themes in the volume do you hope readers will explore?

In addition to those we’ve already touched on, the differences in judicial approaches to Civil Rights are fascinating and significant. The cases are complicated, and the logic of many decisions might be challenged. The Plessy court may be wrong in its conclusion, and the Brown court right in its conclusion, but the logic of the rulings in each case is neither all right nor all wrong.

Also, both cases touch on “social equality.” This issue is central to Loving v. Virginia, a case I consider to be at least as important as Brown or Plessy. Segregation was always driven by a fear of intermarriage, or race mixing. I think the race problem in the US will be solved finally when blacks and whites regard one another, routinely and without controversy, as prospective family members. To build a truly common culture we need to start in the household. Loving v. Virginia addresses that issue in the most profound way.