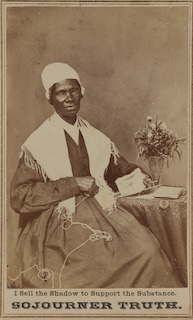

The Many Lives of Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth died on November 26, 1883, aged 86. Yet reports of her death began circulating decades earlier. Abolitionists and women’s rights advocates had built Truth into a prophetic figure, wise and therefore old. Truth, who never learned to read and write, relied on her abolitionist and feminist allies to put her life story into print, primarily through the Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Although based on Truth’s recollections, it was written by Olive Gilbert, conveying Gilbert’s interpretations and misstating some facts.

If aware of her friends’ inventions, Truth was perhaps too grateful to them to object. Sales of her Narrative provided much of her living during an activist career spanning forty years. And perhaps Truth to some extent reshaped her past as she recalled it.

Harriet Beecher Stowe called Truth “the Libyan sybil,” an epithet that stuck. Truth had a tall, erect figure and deep, authoritative voice. She enlivened her speeches by singing. Her direct colloquial style entertained audiences but also touched hearts. To abolitionists and women’s rights advocates, Truth was a godsend. They supported—and used—Truth in their advocacy. Truth cooperated while maintaining her own independent perspective.

Contemporary biographer Nell Irvin Painter, speaking of Truth’s homespun wit, says it masked deep outrage. Had Truth critiqued 19th century America without the screen of folksy humor, she would have repulsed her largely white audiences.

In a sense, Truth died and was reborn several times during her long life. She escaped from slavery in her late twenties, becoming a free person. During a religious vision, she died to sin and fear and was reborn into faith. When about 45, she adopted the name by which we know her today, along with her new profession as an itinerant evangelist and reform advocate.

From Slavery to Freedom

She was born into slavery in about 1797, on the farm of a Dutch family in Ulster County, New York, and named Isabella. As a child and adolescent, she was sold three times. She thought the slaveowner who last held her more trustworthy than the others. When New York legislators voted to begin graduated emancipation on July 4, 1827, she made a deal with him. If she did extra spinning work, he’d free her a year before the law took effect. The slaveowner reneged after she injured her hand and fell behind in the work. Isabella kept at her spinning, and several months later, having finished the promised work, she walked away from the farm before dawn. She found protective shelter and work at the nearby farm of a pious couple who despised slavery, Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen. When the slaveowner called to reclaim Isabella, the Van Wagenens paid him $25 to leave her in freedom.

From Fear to Faith

As a young child, Isabella was taught by her enslaved mother to pray for protection to a god in the sky. Yet her ideas of God remained vague, until, during her first year of freedom she received a vision. She saw God angrily accusing her of sin. Then she felt the presence of a spirit who had always loved her, who protected her from God’s wrath. She called this spirit Jesus, seeing him then as a perfect being God created and endowed with immortality. (Her religious views continued to evolve, for a time causing her to join a communal cult.)

First Public Battle For Justice

In 1828, Isabella—although poor and illiterate—won a lawsuit. Escaping slavery, she had taken with her only one of her five children, her infant Sophia. Her older children would spend many more years in slavery, since New York law established a graduated emancipation. Adults born before 1799 would be freed in 1827; males born later would be freed at age 28, and females at 25. Some slave owners, to recoup the financial loss the law caused them, sold the still enslaved children to Southern traders—a violation of the emancipation law. When Isabella learned that her 4-year-old son Peter had been sold in this way, she resolved to bring him back. With help from local Quakers, she entered a complaint with the Ulster County grand jury. She also borrowed money to hire a lawyer, who located Peter.

The child had been passed from one owner to the next and repeatedly beaten because he was too young to do what they expected. When his mother came to claim him, he protested, fearing yet another beating. Finally reassured, Peter went home with Isabella, who was horrified to find the many scars under his clothing.

Becoming Sojourner Truth

In 1843, Isabella adopted the preaching profession and a new name. She chose “Sojourner,” seeing her life as a journey toward communion with Jesus, and “Truth” for her conviction that a divine spirit spoke through her.

Truth first gained fame for an impromptu speech she made at a woman’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851. Some had questioned the inclusion of black speakers at women’s rights events, claiming their presence blurred the cause with that of abolition. Uninvited, Truth walked onto the stage to assert her sisterhood with all women demanding their rights:

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? . . . I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. . . . As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint and a man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much—for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

Then Truth gave a feminist reading of the Bible. “And how came Jesus into the world?” she asked. “Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part?”

Sojourner Truth in Historical Memory

The convention’s secretary, Marius Robinson, transcribed Truth’s speech in his report of the proceedings. Today, it is remembered for a refrain supposedly woven through it: “Ain’t I a Woman?” These words were invented twelve years later by Frances Dana Gage, who had presided over the convention. In 1863, when she profiled Truth for the New York Independent, Gage probably needed the commission her article earned. (During the Civil War, both she and Truth volunteered to help those fleeing slavery to protection behind Union lines. Gage worked on Parris Island, South Carolina; Truth collected food and clothing for freedmen in Washington, DC.) In Gage’s account, audience members hissed when Truth approached the podium, but roared with applause when she finished speaking. Gage also rendered Truth’s speech in stereotypical Southern slave dialect—an idiom foreign to her.

Another story about Truth became famous when embellished by Harriet Beecher Stowe. At a meeting where Frederick Douglass spoke of his despair that white Americans would ever outlaw slavery—and his growing sense that black Americans would have to win their freedom through force of arms—Truth responded in disapproval: “Frederick, is God gone?” According to Stowe, Truth’s question was the more startling, “Is God dead?’ Stowe also transposed the scene from a small gathering in Ohio to a great meeting in Boston’s Faneuil Hall, saying that Truth’s intervention ended discussion of violence. To Painter, Stowe’s story simply threw another veil over African American outrage. Douglass himself, in his 1892 Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, recalled answering Truth’s question with the words, “No, and because God is not dead, slavery can only end in blood.” And in fact, it was civil war that brought abolition.

Truth did refute claims that discredited her. In 1858, at an antislavery meeting in Indiana, a group of pro-slavery Democrats disrupted the end of her speech, saying the deep-voiced Truth was a man in woman’s clothing. They demanded that some women take her aside and examine her, to see if she had female breasts. Truth stood her ground, saying that while in slavery she had suckled white children when her own children needed her milk. Then she undid her bodice, exposing her bosom and asking her male hecklers if they, too, wished to suck? After emancipation, Truth worked among the unemployed freedmen in Washington, DC, helping them find work and exhorting them to orderly habits. Aware that the defeated Confederates intended to keep the freedmen in servitude, she sought funding for them to migrate to the Midwest and develop their own independent communities. Few supported her in this effort. Meanwhile, Truth’s friend Frances Titus oversaw the printing of expanded editions of Truth’s Narrative, sales of which supported Truth. She died in Battle Creek, Michigan, an invalided former celebrity, visited by the curious, to whom she whispered, “Be a follower of the Lord Jesus.”