The "Era of the Monroe Doctrine is Over"

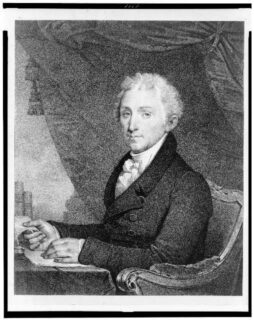

On December 2, 1823, during his annual message to Congress, President James Monroe articulated a foreign policy stance for our nation that would become known as the Monroe Doctrine. He proclaimed a policy of non-interference in the affairs of foreign nations, except in cases when European powers interfered in the Western hemisphere. To communicate the US intention to continue a stance of neutrality in the wars of Europe, he stated:

Our policy in regard to Europe . . . is, not to interfere in the internal concerns of any of its powers; to consider the government de facto as the legitimate government for us; to cultivate friendly relations with it, and to preserve those relations by a frank, firm, and manly policy, meeting in all instances the just claims of every power, submitting to injuries from none.

However, he now warned that the US would not remain neutral when European governments attempted to overthrow newly independent states in the Americas:

It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected . . . . We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers [ie., European monarchies] to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.

President Theodore Roosevelt articulated what would be called his “Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine” in his State of the Union address in December 1904, asserting a right of the US to intervene in other American nations “if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American nations.”

When Roosevelt asserted this, the US had already (in November of 1903) supported a revolution in Panama that had brought its independence from Colombia and enabled the treaty allowing construction of the Panama Canal. For this and other reasons, Latin American observers have tended to view the Monroe Doctrine—especially as interpreted by Roosevelt—as an assertion of the US intent to dominate the other American states. In a little-noticed speech (see this brief historical analysis by Frank Daniels III in The Tennessean) to the Organization of American States on November 18 of this year, Secretary of State John Kerry seemed to have the Roosevelt Corollary in mind when he declared that “the era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.”