The Passage of the 13th Amendment

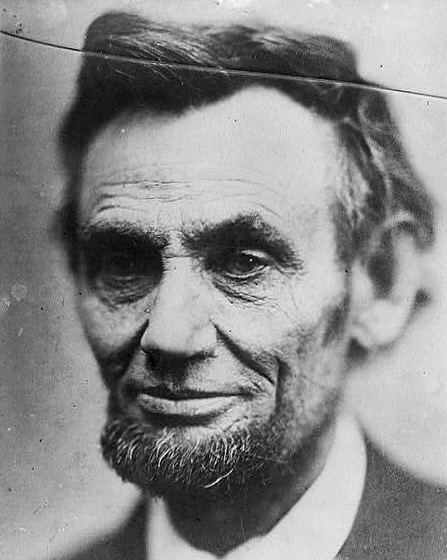

Congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865 was a long-awaited, monumental reform in American life and politics. Yet it accomplished both more and less than we may have been taught to think. It proclaimed an end to the chattel slavery that had existed in America since earliest colonial times. It also introduced to the Constitution a new potential for federal authority over state actions. Yet it left open a loophole that states would exploit to continue profiting from coerced labor and to perpetuate an unjust social order.

Preparing the Ground for the Amendment

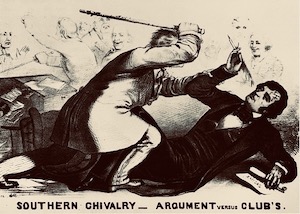

To those who had long advocated for abolition, the outbreak of the Civil War signaled that the time had come. While Lincoln maintained his measured and cautious approach to matters of abolition in his early administration, grassroots activists and influential congressional Republicans began pushing for an amendment to abolish slavery. And they thought the most promising champion of such an amendment would be Senator Charles Sumner. After all, Sumner had been one of the most fierce anti-slavery voices in the federal government in the 1850s — his outspokenness leading to the one incident that American history students likely know about him, his infamous near-death caning on the Senate floor by Congressman Preston Brooks in 1856.

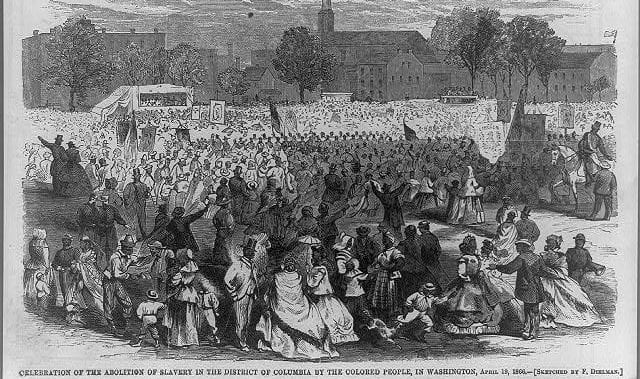

By the beginning of 1864, the Emancipation Proclamation had established a consistent yearlong military policy to welcome and incorporate enslaved people who fled to Union lines, both validating the efforts of those self-emancipating since the beginning of the war and prompting many more enslaved people near active fighting to flee to Union lines. All this activity heightened the moral imperative to permanently abolish slavery. Sumner had recovered from his injuries and resumed his anti-slavery and equal rights work in the halls of Congress. Seizing the momentum, two black abolitionists delivered a petition with 100,000 signatures to Sumner advocating a freedom amendment in February 1864. Sumner took this momentum into committee meetings on the proposed amendment.

Grounding the Amendment in the American Political Tradition

While the final language of the Thirteenth Amendment may seem striking for its time — and certainly more forceful than the strategically precise language of the Emancipation Proclamation, carefully framed as an act of “military necessity” — it was neither as sweeping as some supporters desired, nor was it foreign to federal history. Sumner initially found inspiration in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, and he sought to craft an amendment that proclaimed not only liberty but also equal citizenship. However, the larger Senate Judiciary Committee deemed it more prudent to anchor themselves in the political tradition of the American founders. Accordingly, the committee slightly modified language from Article 6 of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which had banned slavery from the Northwest Territory. So, the proclamation of the Northwest Ordinance —

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted …

— once pasted into the Thirteenth Amendment, became:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Lincoln had referenced the Northwest Ordinance in his arguments defending congressional oversight and regulation of slavery throughout the 1850s. In resurrecting this anti-slavery clause, the Thirteenth Amendment’s wordsmiths aligned themselves with the thinking of their party leader and grounded the amendment in the established American political tradition.

Introducing a New Conception of Federal Authority

While Sumner may have been disappointed that his equal rights clause didn’t make it into the final amendment, the Committee did adopt his preferred phrasing for Section 2 — language with striking ramifications for American federalism:

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

This statement suggested a new constitutional posture. If the first five words of the First Amendment — “Congress shall make no law” — established the stance of the Bill of Rights toward political threats and federalism, “Congress shall have power” presented a very different attitude. While the Bill of Rights supposed the central government to be a threat to liberty, Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment presents the central government as (in Sumner’s later words) the “custodian of liberty” against threats from state governments. So this language (later repeated in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments) explicitly empowered Congress to enforce, and not merely to declare, freedom — to police the work of Reconstruction. (Alas, we know that after a brief period of enforcement, the Southern backlash against Reconstruction, and a shifting Northern emphasis on reunion over reconstruction, led the federal government to retreat from this work. So the power lay largely dormant for generations until the Second Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century.)

The Senate adopted the eventual Thirteenth Amendment in April 1864 by a 33-6 vote, sending the legislation to the House of Representatives — where it stalled in June. A combination of resistance and reticence (particularly from border-state Unionists and Northern Democrats) denied the amendment the two-thirds majority necessary for adoption. It would take over half a year, and another election season, for that majority finally to cohere.

How the 1864 Election Led to Congressional Passage

As he explained in a letter to Senator J.T. Hale in January 1861, Lincoln believed that “carr[ying] an election on principles fairly stated to the people” constituted a political mandate. In other words: platforms and campaigns matter. The 1860 Republican Party Platform opposed the expansion of slavery without explicitly threatening the institution in the states where it already existed — points that Lincoln reinforced in his First Inaugural Address. Lincoln’s antislavery actions in his early administration were accordingly cautious, pushing decentralized emancipation efforts through local action in border states and Union-occupied territories. After issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, the Union effort became an increasingly explicit freedom campaign — militarily, but also politically. The Congressional road to the Thirteenth Amendment can be seen in this light.

In the roughly year and a half between the Emancipation Proclamation and the 1864 campaign season, Congress passed a number of smaller antislavery measures (building up to the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act in June 1864). Meanwhile, signatures on grassroots abolition petitions delivered to Congress grew to 400,000 throughout early 1864, lending popular support to these political efforts. The 1864 Republican Platform was a culmination of this public and private action, redoubling the party’s antislavery commitments by both underscoring the constitutionality of the Emancipation Proclamation (against its political opponents) and endorsing an abolition amendment to the Constitution — statements that, in tandem, affirmed the war effort to be as much about freedom as union.

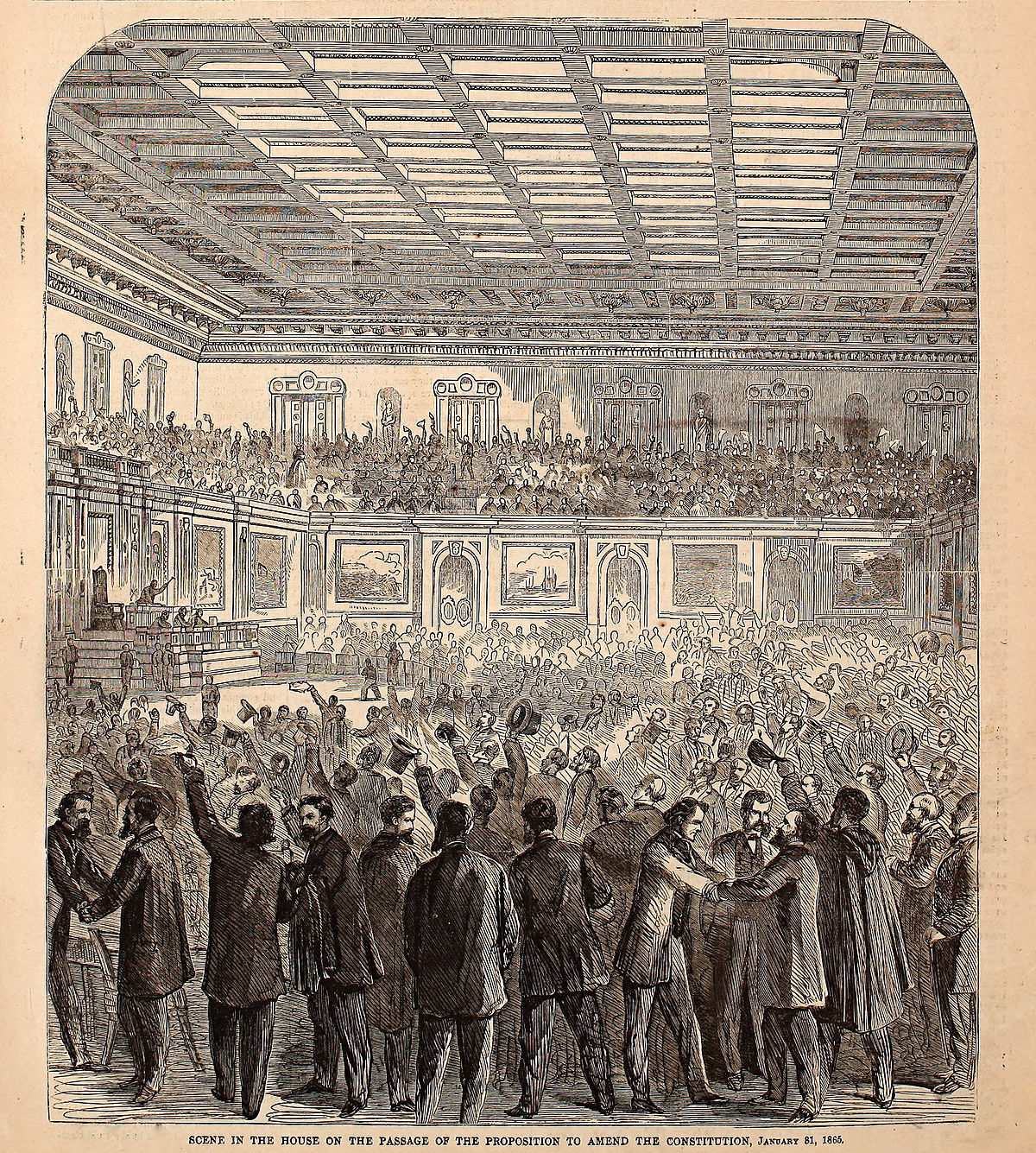

These platform points stood more as policy commitments than active campaign material through the 1864 election season; Republicans remained cautious on the campaign trail, cultivating antislavery sentiment without forcefully stumping for it. Nonetheless, GOP congressmen took the party’s success that fall — in the presidential, congressional, and key state-level elections — as a mandate to push their abolition amendment through to passage and ratification. At the beginning of the lame-duck final session of the 38th Congress, Lincoln signaled his commitment to abolition. He declared in his 1864 Annual Message that the “voice of the people … [had been] heard upon the question” of slavery in the 1864 election. Less than two months later, the House finally acted on that accord. Enough June holdouts changed their votes to surmount the two-thirds majority threshold needed for adoption. On January 31, 1865, the House voted 119-56 in favor of the amendment. President Lincoln signed the bill the following day, sending the amendment on its ratification journey (which would be completed in December).

The Unfinished Work of Abolition

While the Thirteenth Amendment was hailed as a great step forward in the American experiment, the punishment exemption in Section 1 (“except as punishment for crime”) left a glaring loophole by which states could impose second-class citizenship through racist legal codes. The rise of black codes in the South — which spread as the Thirteenth Amendment was being ratified throughout 1865, and boomed after ratification that December — sought to reestablish a social order as close to slavery as possible while technically complying with federal law. These abuses of power (among other unfinished Reconstruction matters) provoked Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and ultimately the Fourteenth Amendment, both of which sought to establish clearer terms for citizenship and freedom — and more closely approximated Charles Sumner’s initial hopes for the Thirteenth Amendment.

In recent years, reformers and activists have focused on the punishment exemption to critique exploitative prison work conditions. And in the November 2022 midterm elections, five geographically and politically diverse states voted on initiatives to strike punishment-exemption clauses from their state constitutions: Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee, Oregon, and Vermont. The initiatives passed in all these states except Louisiana, where legislators abandoned their own measure in fear that its ambiguity might ironically create further loopholes. It remains to be seen what effect this momentum will have on incarceration practices or prison industries — or even on potential revisions of the Thirteenth Amendment itself — but this process echoes the journey of the Thirteenth Amendment even as it critiques it. Like the Thirteenth Amendment, these modern initiatives have arisen through the collaboration of politicians and citizens, all advocating for structural change. Then as now, the work requires all of us who engage with it — as students of history or citizens in the present — to insist on adherence to the principles of liberty and equality in our governmental institutions.

Additional Sources

Ayers, Edward. The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America. New York: Norton, 2017

Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: Norton, 2010

Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty: An American History, Brief Sixth Edition. New York: Norton, 2020

“The Senate Passes the Thirteenth Amendment” United States Senate.