The Trial of the Murderers of Emmett Till

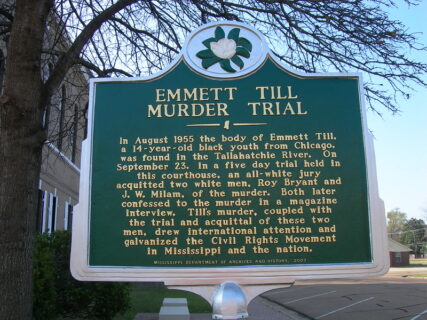

Ceiling fans stirred the sweltering air deep in the Delta on Friday, September 23, 1955. Twelve white men exited the jury room in the Tallahatchie County courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi. During the last several days, this all-white jury had heard testimony in a murder trial. Two white men, J.W. Milam and his half-brother Roy Bryant, were charged with the murder of Emmett Till, age fourteen, an African American who had come South from Chicago to visit family. The courtroom was jammed, as it had been all week, with more than 200 hundred observers, the majority white, attending. Dozens of reporters were also present, filing stories with both regional and national newspapers. The sheriff segregated the black reporters, requiring them to cram around a folding table in a corner while the white press was seated close to the judge and jury.

The courtroom crowd indicated there was something unique about the proceeding. It was the fact it was being held at all. The state of Mississippi rarely investigated, let alone prosecuted, the murder of blacks by whites. Between 1882 and 1951, white mobs lynched 534 African Americans in Mississippi without fearing arrest, trial, or conviction. “That river’s full of [blacks],” a white man matter-of-factly told a reporter for The Nation, referring to the Tallahatchie River, where Emmett Till’s bloated, mutilated body had been found.

The arrest and trial of Milam and Bryant was an exceptional occurrence. It also appeared to be a fair proceeding. Reporters praised Judge Curtis L. Swango for his even-handed oversight. The prosecutor Gerald Chatham had put together a rock-solid case, producing several witnesses who saw the accused kidnap Till and heard the merciless beating the boy endured before he was shot in the head. In his summation, Chatham reminded the jurors that the defendants had freely admitted to seizing Till from his uncle’s home, where he was staying. “They murdered that boy, and to hide that dastardly, cowardly act, they tied barbed wire to his neck and to a heavy [cotton] gin fan and dumped him in the river for the turtles and the fish.” But would an impartial judge and overwhelming evidence of guilt matter?

“Gentlemen of the jury, do you have a verdict?” Judge Swango asked.

“We have,” the foreman answered, and then delivered the verdict.

Emmett Till was a baseball-loving teenager with lots of friends. He liked to tell jokes. Polio, which had afflicted him at age six, left him with a stutter and weak ankles, but otherwise he had recovered fully. His mother, Mamie Bradley, initially resisted letting her only child, nicknamed Bobo, travel to Mississippi with two cousins who also lived in Chicago. She had been born in Tallahatchie County. Her family moved to Argo, Illinois, just south of Chicago, in the 1920s. They were part of an ongoing migration that brought approximately six million black southerners to destinations in the North and West between 1910 and 1970. Chicago became known as a promised land, but the title belied the realities of northern racial discrimination. Chicago was one of the nation’s most racially segregated cities, the separation enforced not just by realty, banking, and municipal practices, but also by violence. “Bombings are a nightly occurrence” whenever blacks move into all-white neighborhoods, a city agency reported in 1954. In one incident, 2,000 whites mobbed an apartment building after a black couple bought it.

As a result of residential segregation, Emmett attended an all-black public school. After his murder, some commentators suggested that because he had grown up in the North, he wasn’t familiar with the customs of white supremacy, leading to the seemingly innocuous action that led to his violent death. Yet as historian Timothy B. Tyson notes, coming from “one of the toughest and most segregated cities in America,” the young man “did not have to go to Mississippi to learn that white folks could take offense even at the presence of a black child, let alone one who violated local customs.”

Emmett’s “violation” of local custom occurred on August 24, 1955. A carload of teens, including his two cousins, drove to a small store in the town of Money. Roy Bryant owned the store. That day, his twenty-one-year-old wife Carolyn was minding the register. The store catered to black customers, some of whom were socializing outside when the car arrived.

Emmett and one of his cousins went in to buy candy. What transpired next, in a mere moment, set in motion the events leading to his horrific murder. Emmett may have brushed Carolyn Bryant’s hand when he gave her money for his purchase. He may have addressed her familiarly, may even have asked if she would go on a date. After decades of silence about the incident, Bryant admitted she couldn’t remember exactly what happened. But she did remember, with certainty, what had not happened in the store. Emmett had not seized her hand. He had not chased her down the counter. He had not grabbed her around the waist with both hands. And he had never said “You needn’t be afraid of me. [I’ve], well —- with white women before.” A black witness who watched the interaction between Emmett and Carolyn through the store’s window confirmed that none of this happened.

At trial, however, Bryant claimed Emmett had chased and grabbed her and spoken coarsely. Although Judge Swango dismissed the jury during her testimony, her husband and brother-in-law’s defense attorneys were able to present these lies to observers and the press, knowing that word would reach the jurors. A black man had violated an ironclad rule of white supremacy—he had (allegedly) propositioned a white woman.

Word of the incident at the store spread, reaching Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam. Early on the morning of Sunday, August 28, the two men, armed with .45 automatic pistols, pounded on the door of Emmett’s uncle, Moses Wright, a preacher and sharecropper. They demanded to see the “boy from Chicago” who “did the smart talking up at Money.” Despite Wright’s efforts to placate the angry white men, they took Emmett to their truck and drove away. At the trial, Wright took the witness stand and identified both Bryant and Milam as the kidnappers, calmly stating “There he is” when the prosecutor asked him to point out Milam. The tension in the courtroom was palpable: a black man testifying against a white man in a murder case risked being killed. When asked how he found the courage to do that, Wright replied, “Some things are worse than death. If a man lives, he must still live with himself.”

Had H.C. Strider, the sheriff of Tallahatchie County, had his way, Wright would never have taken the stand, for there would have been no trial. When Emmett’s body was found in the Tallahatchie River on August 31, Strider demanded the body be buried that day even as he was claiming the authority to investigate the murder itself. The courage, fortitude, and foresight of Mamie Bradley stymied the sheriff’s blatant attempt to cover up the crime. Though she had been consumed with fear and dread for three days at the news her son had not been seen since two white men kidnapped him, and she had just learned her dead son had been found, she insisted the body be sent to Chicago for burial. She had already notified Chicago police and press about Emmett’s disappearance. The arrival of her son’s sealed casket in Chicago on September 2 thus brought a huge crowd, including reporters, to the station. As Bradley explained decades later, despite being in mourning for her son, she “took the privacy of my own grief and turned it into a public issue, a political issue, one which set in motion the dynamic force that ultimately led to a generation of social and legal progress for this country.” Then she overcame the strenuous objections of the undertaker and demanded he open the casket so that she and the world could see what had been done to her son. Photographs of Emmett’s swollen, shattered head and body, which the undertakers couldn’t repair, received national and international attention. Over several days, an estimated 250,000 people viewed the casket (topped with an airtight glass lid) at the funeral home. Had Mamie Bradly not fatefully decided to gain custody of her son’s body and present the shocking evidence of how he died, the murderers would never have ended up in court.

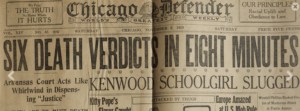

“Not guilty!” the jury foreman announced to Judge Swango and the courtroom. Confident of their acquittal, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam had lit cigars before the jury returned. They posed for photographs outside with their families, smiling and accepting congratulations.

Mamie Bradley, Moses Wright and their families and supporters were not surprised by the verdict, either. Incontrovertible evidence and an impartial judge weren’t enough to override allegiance to white supremacy in the Delta. The jurors never intended to let the evidence dictate their vote. That their “deliberation” took just over an hour was a pretense—the sheriff had told them to make it “look good.” But Bradley, among many others, resolved that her son’s murder should be a catalyst for civil rights. Black congressman Charles C. Diggs (D-Mich.), who went to Mississippi to observe the trial, organized a protest in Detroit two days after the verdict that drew 4,000 participants. The event raised more than $14,000 for the NAACP. Bradley addressed a crowd of 10,000 in Chicago, then traveled to New York to speak with NAACP leader Roy Wilkins and the venerable civil rights activist and labor leader A. Philip Randolph. Across the North and South, a coalition was cohering, bringing together labor unions, clergy and their congregations, politicians, and young activists, to make sure Mississippi did not, once again, get away with the murder of a black man for violating the customs of white supremacy.

And not just Mississippi. To believe that Till’s murder was the unfortunate result of the peculiar, violent ways of a particular area meant overlooking the undeniable existence of racial discrimination and violence across America. Although the modern civil rights movement was well underway before Emmett Till’s murder, Mamie Bradley’s refusal to let that crime be covered up brought renewed urgency and resolution to the movement. With Mamie Bradley by his side, Randolph proposed a march on Washington to demand action from the federal government to protect black citizens from the kind of violence that had taken Till’s life. Such a march did take place, as did several others, eventually culminating in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Passage of the Civil Rights Act soon followed.

The United States has made notable progress in fulfilling the “social and political progress” Mamie Bradley hoped her son’s murder would be a catalyst for. Yet crimes motivated by racial bias still occur frequently, as evidenced by the FBI’s just-released report Hate Crime Statistics, 2020, with African Americans being more likely to be targeted because of their race than any other group.

Bibliography:

Equal Justice Initiative, “FBI Reports Hate Crimes at Highest Level in 12 Years,” September 9, 2021.https://eji.org/news/fbi-reports-hate-crimes-at-highest-level-in-12-years/

Mabie Till-Mobley and Christopher Benson, Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime

That Changed America (New York: Random House, 2003)

Timothy B. Tyson, The Blood of Emmett Till (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017)

Stephen J. Whitfield, A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till (New York: Free Press,

1988; reprint, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991)