The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921

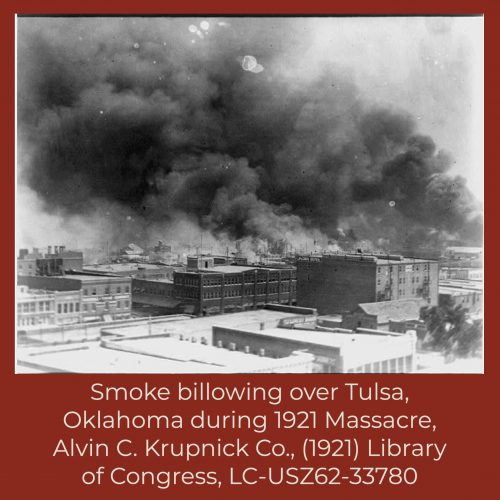

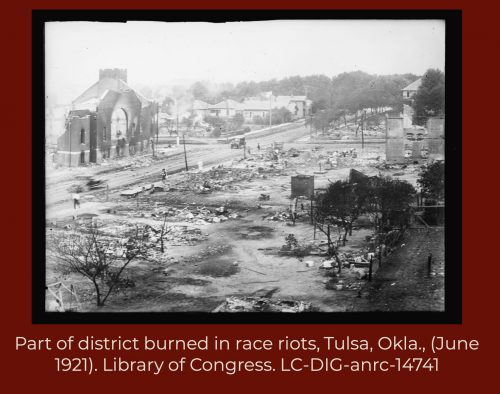

On June 1, 1921, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a war zone. Just before dawn, a loud whistle signaled a 10,000-strong army to swarm across railroad tracks and besiege the neighborhood of Greenwood, whose defenders had kept the attackers at bay throughout the night. Just three years earlier, some of the attackers and defenders had worn the same uniform, that of the United States Army. Now they faced each other as enemies. Uniformed Tulsa police also numbered among the attackers, firing their service weapons at citizens they had sworn an oath to protect. Though the “war” was just hours long, its ferocity killed almost 300 Tulsans and left a thirty-five square block area a smoking ruin. Thousands were homeless, their houses and businesses a total loss. Tulsans had destroyed a substantial part of their own city—why?

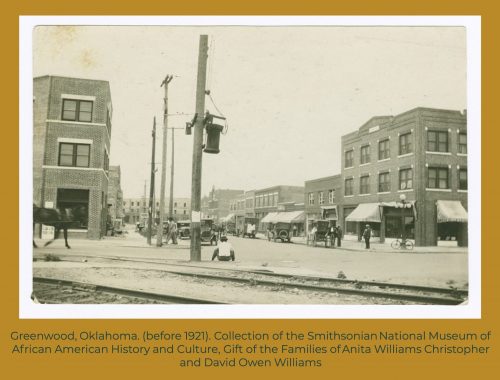

Because the attackers, who were white, could no longer tolerate the presence of African American economic success within Tulsa. Greenwood, home to approximately 10,000 African Americans, was one of the most prosperous black communities in the country. Entrepreneurship thrived. J.B. Stradford, born enslaved in Kentucky in 1861, had built the nation’s largest black-owned hotel. The establishment anchored the north end of the Greenwood business district, later called Black Wall Street because of the value of its businesses and property. J.H. Goodwin owned a real estate office and a funeral home. The Gurleys, a married couple, opened the People’s Grocery and a hotel. The Williams family owned and operated a confectionary and the 750-seat Dreamland Theater.

Greenwood developed in part because of Tulsa’s racial segregation, which prevented blacks from living elsewhere in the city and reserved jobs in the booming oil industry for whites. Despite being denied equal opportunity and rights, entrepreneurs like Stradford had prospered, amassed wealth, and built a community. They also fought Jim Crow. Stradford sued the railroad that made him sit in a segregated car. Goodwin’s wife called Greenwood’s attention to the high school that required black students to do whites’ laundry. The Dreamland Theater doubled as a community center where residents planned anti-segregation efforts. Greenland’s leaders and residents recognized that their economic success and resistance to white supremacy aroused considerable resentment, even hatred, among white Tulsans. As A.J. Smitherman, publisher of The Tulsa Star, wrote, the black American lives “in the land of the free but is not free. He is despised and rejected [by] his brothers in white.” Smitherman knew well that racial hatred bred violence; he had long urged African Americans to use armed self-defense to stop mobs.

The threat of such violence was frighteningly real. Throughout 1919, antiblack collective violence surged in the United States. In Washington, D.C., white mobs attacked African Americans after inflammatory newspaper articles stirred white anger at alleged black crimes. In Chicago, white gangs violently evicted blacks from homes in majority white neighborhoods and murdered black packinghouse workers. The worst antiblack violence occurred in Phillips County, Arkansas. When black sharecroppers formed a union, white landowners, law enforcement officials, and vigilantes carried out a pogrom that killed more than 230 African Americans. Violence against blacks continued into 1920, culminating in the killings of black voters on election day in Ocoee, Florida. Wherever they formed, white mobs had shared purposes: to drive blacks from jobs whites wanted; to stop the integration of residential neighborhoods; and to protect the larceny embedded in the sharecropping economy. Blacks who prospered were especially vulnerable to attack, for their success belied a central tenet of white supremacy, the supposed inferiority of African Americans. Fortunately, Greenwood had avoided such violence. Then Tulsa police arrested a young black delivery worker for allegedly assaulting a young white woman in an elevator on Memorial Day, 1921.

The assault never happened. Tulsa’s two white newspapers, however, ran lurid stories. By Tuesday evening, May 31, several hundred white men had gathered around the county courthouse where the young man was jailed. At 9:30 p.m.,thirty black men from Greenwood informed the sheriff they had come to protect the prisoner from a lynching. The sheriff convinced them to leave, but as the number of whites swelled to an estimated 2,000, several carloads of armed black men, many of them World War I veterans, returned. A white man seized the rifle of a black man, leading to an exchange of gunfire. Armed white men pursued the black men to Greenwood, where—as mentioned earlier—residents set up a line of fire that deterred the attackers throughout the night. John Williams, helped by his teenage son W.D., kept looters away by firing from the window of their home, which was above their confectionary. Resident Mary E. Jones Parrish later praised the “brave boys of ours [who] fought gamely and held back the enemy for hours.”

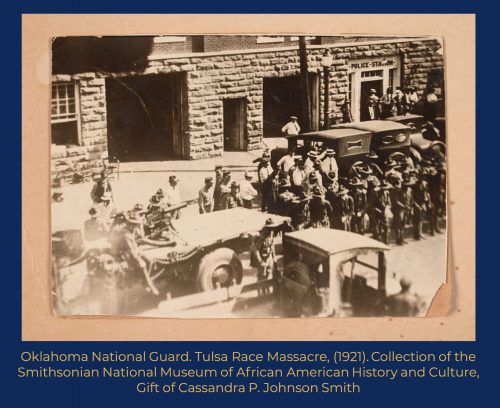

But Greenwood was outnumbered and outgunned. Deputization by police and the sheriff added 500 armed white men to the force attacking Greenwood. Troops from the all-white Oklahoma National Guard unit based in Tulsa encouraged white veterans to form posses. The troops themselves dispersed to guard the city’s armory and utilities, but not Greenwood. White rioters had falsely told the guard’s commanding officer that Tulsa’s blacks were rising up to kill whites. In fact, whites were killing African-Americans, looting black homes and businesses, and leveling Greenwood. The attackers deployed machine guns and carried cans of kerosene and matches. After forcing blacks to flee their homes and businesses with hands held high, looters ransacked the buildings and lit them on fire. W.D. Williams saw a white man run off with his mother’s fur coat. J.B. Stradford witnessed a “raiding squad” break into the drugstore in his hotel. The marauding of Greenwood was so methodical that it included aerial bombardment. Biplanes, which oil companies may have furnished, fired at blacks and released improvised fire bombs.

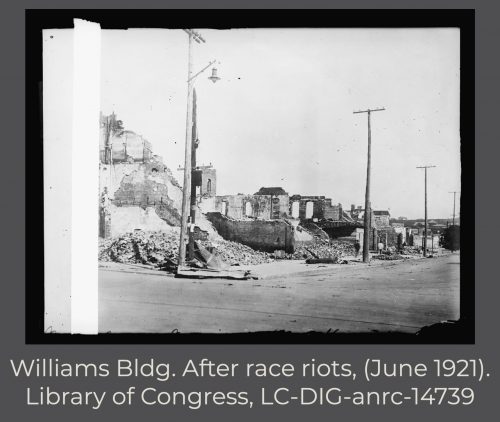

Oklahoma’s governor ordered outside National Guard troops into Tulsa to end the massacre. Martial law was imposed at noon; by then, much of Greenwood had burned to the ground in one of the worst racial pogroms in U.S. history. The mob’s systematic arson destroyed more than 1,100 homes. Also lost: more than seventy businesses (including Stradford’s hotel, the Williams’ Confectionary, and Smitherman’s newspaper office), twelve churches, a hospital, and a school. The loss of black residents’ assets and property is estimated at between 20-200 million dollars in today’s currency. The official death toll was set at thirty-eight (twenty-eight blacks, ten whites), but as many as 300 Tulsans, almost all them black, died. No whites were arrested for the killings and looting, but the troops rounded up Greenwood residents and detained them at the city’s convention hall and fairgrounds. White officials searched for Stradford at the convention hall—they wanted to charge him with inciting a riot. For these men, and those who had destroyed Greenwood, Stradford’s real ‘crime’ was that “he’s been here too long . . . and taught the [blacks] they were as good as white people.”

Stradford eluded arrest and relocated with his family to Chicago. Officials charged more than fifty other African Africans for the massacre that had killed their neighbors and loved ones and left them penniless and homeless. Sadly, the perversity of arresting victims for the massacre inflicted upon them wasn’t the final injustice. Property and business owners received no compensation for their losses. White land speculators took advantage, purchasing lots for a fraction of their worth. (Stradford, for example, sold his land for one dollar.)

For decades, the massacre remained a hidden memory, an ignored history. But survivors and their descendants preserved evidence and stories. In the 1970s, these sources proved invaluable to historians such as Scott Ellsworth, one of the first scholars to thoroughly research the massacre. In 1997, the state legislature created the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921; since 2002, state public schools must teach about the destruction of Greenwood. Most recently, a city initiative is supporting commemorative art projects and searches are underway to identify possible mass burial sites of the victims whose deaths were never officially recorded.

This attention, long overdue, is commendable; it is also cautionary. Tim Madigan, who has written a book on the Tulsa Race Massacre, remembers his shock at first learning of the event after working as a reporter for many years: “How could I not have known about something so horrible?” That’s a question we should ask ourselves, and not just about Tulsa. We should ask it about the long national history of racial violence directed at African Americans. Ignoring this history doesn’t make it disappear, but learning it will go a long way to understanding race relations in the United States today.

Bibliography

Ellsworth, Scott. Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

Luckerson, Victor. “The Promise of Oklahoma: How the Push for Statehood Led a Beacon of Racial Progress to Oppression and Violence.” Smithsonian. April 2021. Pp. 26-35.

Hirsch, James S. The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

Madigan, Tim. The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin’s Press, 2001.

—- . “American Terror: Confronting the Murderous Attack on the Most Prosperous Black Community in the Nation.” Smithsonian. April 2021. Pp. 36-51, 76 ff.