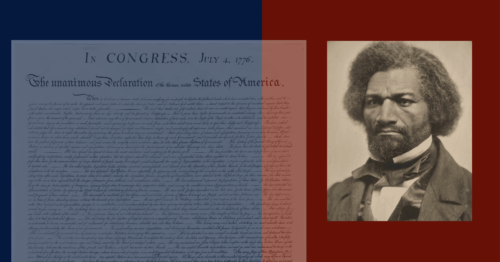

Truths Held in Tension: Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Among speeches denouncing slavery, perhaps the most effective ever delivered is Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Douglass proposed to answer this charged question on the day following its annual celebration, July 5, 1852. He spoke to the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York, a feminine audience who needed no persuading of slavery’s evil. Yet Douglass intended this speech for the nation as a whole – perhaps most of all for those still vacillating between repugnance at slavery and concern to keep sectional tensions at bay. (Indeed, he had the speech printed immediately after delivering it so as to sell copies as he traveled to promote the abolitionist cause).

Douglass had been arguing the cause of abolition for at least a decade when he composed this speech. He felt that he and the abolitionists with whom he worked had thoroughly debunked the social, scientific, and ethical arguments made by Southerners in defense of slavery. Yet they had seen no political progress toward the ending of slavery. Instead, the Compromise of 1850 had sustained the balance of power between free and slave states, making possible the extension of slavery into new territories. Moreover, with the Fugitive Slave Act, the compromise obtruded the slave states’ power onto free soil. It strengthened slaveholders’ ability to track and reclaim slaves who escaped into freedom, since it required law enforcement officials in free states to assist in such efforts.

In this excerpt of the famous speech, Douglass uses the rhetorical strategy of apophasis. He reminds his audience of all the arguments refuting slaveholders’ self-justifications – by claiming that they are so well-understood as to need no further recitation. The tactic allows him to re-argue his case while asserting that the time for reasoned argument has passed, and that the time for action has come.

If the word “paradox” captures the rhetoric Douglass deploys in this speech, it might seem also to characterize his carefully reasoned argument. Douglass proclaims and holds in tension ideas that many abolitionists of the time – and even some commentators today – see as contradictory. He argues that slavery’s existence renders American “republicanism a sham;” yet he refuses to label as hypocrisy the assertion of human equality in the Declaration of Independence. [Indeed, the first half of the speech gives an eloquent account of the founding fathers’ fight for liberty.] Indirectly acknowledging that the founders compromised with slaveholders to bring them into the union, Douglass denies that the founders admitted to the Constitution any reference whatsoever to slavery itself, let alone to slaveholding as a “right.” Directing withering sarcasm at those still compromising with Southern slaveholders, Douglass never allows – as some white abolitionists did – that division of the country into two sections would be preferable to compromise.

Douglass embraces the ultimate paradox in his conclusion, pivoting from “the dark picture I have presented of the state of this nation” to a prophecy that emancipation must come, and will come soon. Invoking “the great principles” of the Declaration of Independence, the spread of knowledge and enlightenment, and the governing justice of God, he redirects the outraged conscience of his audience toward hopeful action, in confidence that their cause will prevail.