Uncovering the Lost Stories of Frontier Settlement

Where do you find the unexamined documentary history of the Great Plains during the time of settlement and early statehood? In the archives of county courthouses, Donna Devlin has found. Devlin, a 2012 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, just completed a PhD in United States History with a Specialization in Nineteenth Century America at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Interested in the development of legal systems on the western frontier during the latter half of the 19th century, Devlin has spent hours combing through case files and other court records in rural courthouses of Nebraska and Kansas. Her dissertation examines “how women worked within the law to address sexual violence on the late nineteenth-century Great Plains.” Court records, she finds, capture a multitude of untold stories that, when considered together, alter our understanding of the challenges faced by immigrants, women, and minorities settling in America’s frontier zones.

A Wealth of Documents, Precariously Housed

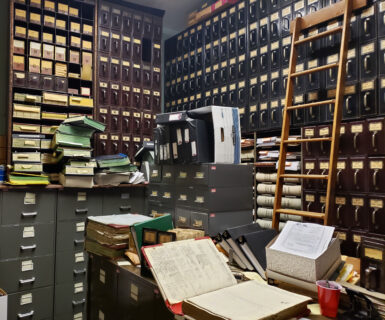

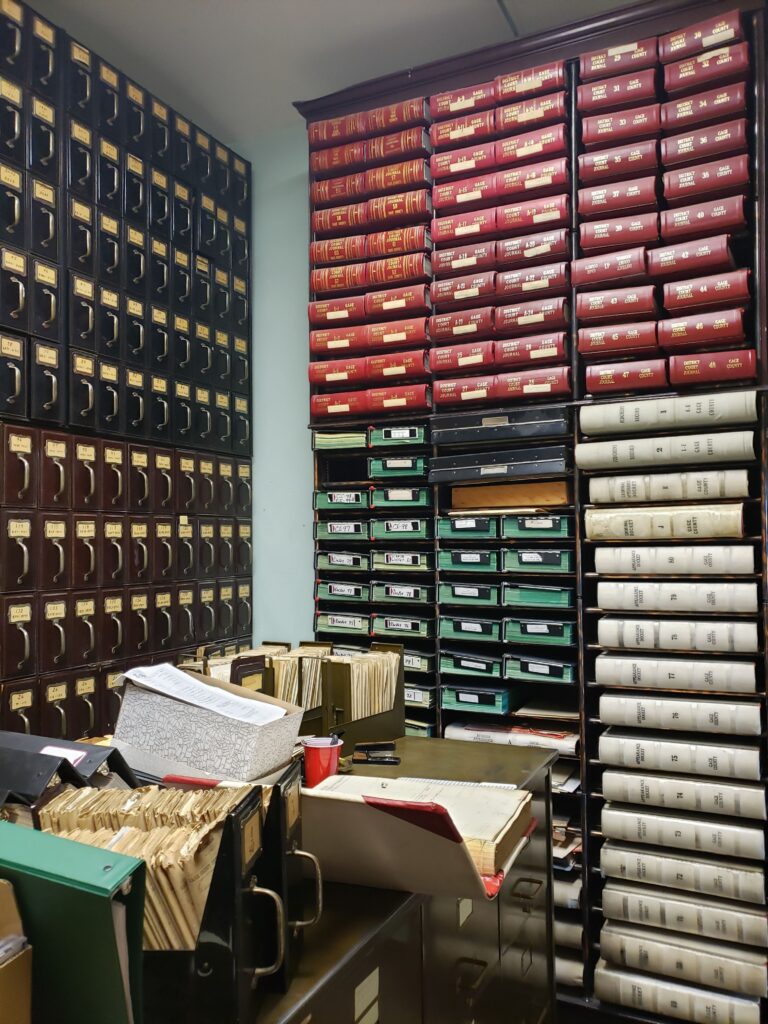

Devlin has pored through original, hand-written records that have been touched but little since their creation. “Most people would probably assume that the records dating back to the mid-19th century in Kansas and Nebraska are all safely housed in the state archives, and microfilmed and organized. None of that is true,” Devlin said. Instead, in most of the 198 counties that comprise the two states, court records—whether land records, school records, or records of civil or criminal trials—are housed in small rural county courthouses, “in various states of organization, or disorganization.”

An early research trip took Devlin to a single, vaulted-ceiling room in the Gage County Courthouse in Beatrice, Nebraska. The county’s records have been housed there since 1892, after a new courthouse was built on the site of the original. “While constructing the second building, they had to move government functions, including court, all around town. So, there are records missing from this period,” and perhaps from others.

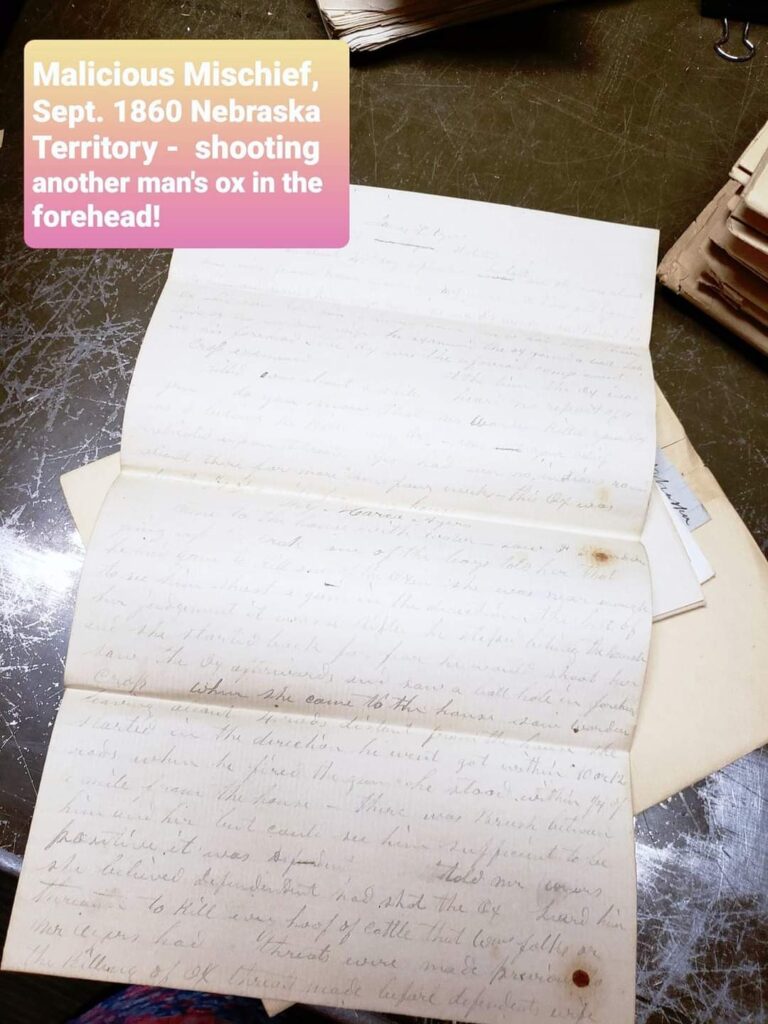

When states lack retention laws for court documents, Devlin said, counties which have run out of archival space, or staff and funds to care for them, have purged some older files. Still, the first case file Devlin pulled from the Gage County archives provided a surprising window into the early settlement of the plains. “It was from 1860, and described the prosecution of a farmer who was mad at a neighboring farmer, so what did he do? He went over and shot the neighbor’s oxen in the head! Who besides me has read that case file since 1860?”

Ethnic Diversity—and Competition—on the Plains

These groups typically settled in ethnically distinct clusters. Competition among them arose as state legislators deliberated where to situate county seats, the new hubs for commerce—the places where trains were routed and hotels, stores and banks were built. Court records show disputes arising between townships, then resolving as decisions were made. But the records show little resolution of the challenges victims of sexual violence faced when seeking justice.

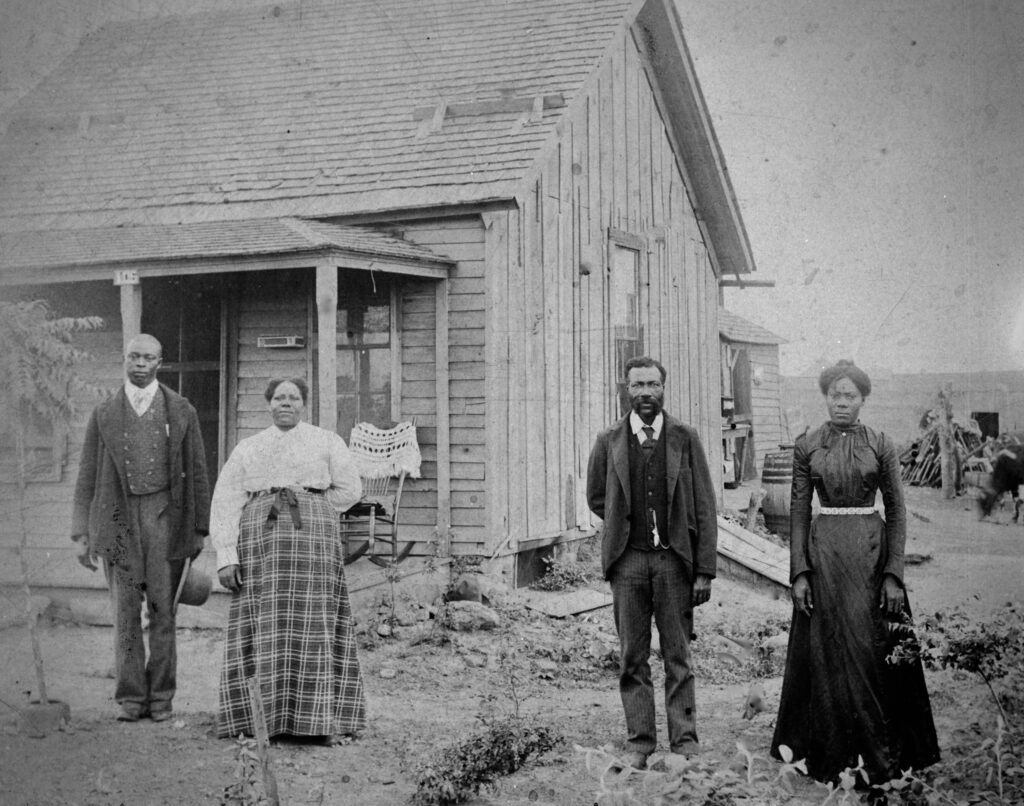

Besides conflicts between neighbors, court records also reveal, through deeds and land disputes, the diverse ethnicities of those who traveled to the Great Plains—Germans, Swedes, Russians, and a sizeable group of African Americans who migrated from southern states bordering the Mississippi River. Many of the latter are called “Exodusters” because they saw their migration as an exodus from the increasingly restrictive conditions they dealt with after Reconstruction ended.

The Legal Response to Sexual Violence on the Great Plains

Devlin, in her dissertation, focuses on five detailed case studies, supporting each study with data about other comparable cases documented in the court records. One study involves a sexual assault near Nicodemus, Kansas, perhaps the most well-known community of Exodusters. Using records she found in the courthouse of Graham County, Devlin traces this story of an eleven-year-old girl who was raped by a twelve-year-old boy living on a neighboring farm. The rape occurred only months after the families of both children arrived in the county, having travelled together in a single colony of Exodusters. The girl’s father, the Reverend Daniel Hickman, brought charges against the boy; but almost a year and a half passed before a final judicial decision was issued. “When the crime occurred, Graham County was barely organized; the accused was taken to another county to be jailed and tried. The legal actors in the case were, let’s say, less than skilled. In the local newspaper there is a story about bad whiskey and a brawl between the legal actors of this case, and about lost papers.”

Ultimately, after two trials, the presiding judge partially ignored the laws of Kansas when instructing the jury. “He reached into his back pocket and pulled out the 17th-century perspective of English Common Law and Justice Sir William Hale. Citing Hale, he advised the jury that a boy under the age of 14 was, we must assume, physically incapable of committing a sexual crime.” Ironically, according to Kansas law of the time, the age of consent for females was only ten. “Kansas law said that the victim in the case was capable of engaging in a sexual act; but according to the judge, the older boy was incapable of the same. The boy was found not guilty.”

“Not a whole lot has changed, it seems, in the prosecution of the crime of rape. At the later of the two trials, the young girl probably no longer showed signs of recent trauma. If the jury doesn’t see in the courtroom an obviously beaten, downtrodden victim . . . if it’s 18 months later and they see an older girl who now seems fine, does that affect the outcome of the trial?”

A Classic Novel Depicting Sexual Violence on the Great Plains

Another of Devlin’s case studies has already led to articles she published separately in the Willa Cather Review (March 2020) and the Western Historical Quarterly (Spring 2022). This study centers on an assault in Nebraska suffered by Annie Sadilek, a friend of Willa Cather and the real-life inspiration for Cather’s 1918 novel, My Ántonia. The novel alludes to this assault, but in ways that diffuse the violence involved, or allow Cather to speak of it without indecency. The known story, as largely replicated in the novel, sees Ántonia becoming pregnant by a suitor who abandons her. But prior to this, Ántonia had lost her job after associating with a man who sought a kiss on her employer’s porch, but received a slap from her instead. She then suspected that her new employer intended to attack her, so she traded sleeping quarters with her friend Jim Burden. Burden was attacked during the night, but managed to get away. In another incident, Ántonia is startled by a tramp passing through her farm; after exchanging words with Ántonia, he commits a grisly suicide, throwing himself into a mechanical reaper. (“Accidental deaths by mechanical reaper actually happened,” Devlin said; “I’ve seen newspaper accounts.”) Those who remove the tramp’s mangled body from the machine find a knife in the pocket of his shredded trousers. Interestingly, in real life, Annie Sadilek described a similar odd detail about her assailant. In the actual court documents, Sadilek testified to being attacked by a man walking her home from a dance who then used “shears or a knife,” pulled from his pocket, to cut down her drawers.

Devlin suspects that Cather incorporated these fictional incidents in order to transmute the violence her friend suffered into something less shocking, while wresting poetic justice from it. “There are a lot of dark elements in Cather’s work,” Devlin says. “I think she in some ways produced a more accurate assessment of Great Plains life than we have found in history books.”

The Problematic “Rural Perspective” on Sexual Violence

Devlin concluded her dissertation with a study of a twenty-first century case in Kansas. A woman who was sexually assaulted at college reported her rape to police, and evidence of it was gathered in a rape kit. When the McPherson County prosecutor refused to bring charges of rape against the accused, the young woman and her parents contacted the Kansas Attorney General. This move seemed to prompt a response from the county attorney who then filed battery charges. Outside counsel eventually prompted the young woman and her family to use an 1887 law (available in Kansas, Nebraska, and four other states) that allows plaintiffs to gather signatures on a petition so as to compel a recalcitrant prosecutor to summon a grand jury.

“The family circulated the petition, but it didn’t work in their favor. Although this action compelled the county attorney to convene a grand jury, the panel, composed of local legal actors, opposed bringing charges for rape. The court allowed the battery charge to stand and the accused received probation.” But Devlin has no doubt that the young woman suffered a rape. “I interviewed her and her mother, who kept a detailed record of events over the years. And I saw the photos of the bruises on her neck firsthand,” she said.

Devlin thinks sexual violence needs to be considered from “a rural perspective.” Rural communities are small and close-knit. “There are interconnections between the people who are elected to serve and those they’re supposed to be serving. Things get swept under the rug or forgotten. Oversight is difficult; many of these counties are hours and hours away from state capitals and the state attorney general. Besides that, a lot of these issues are first being handled by local judges, and multiple counties are being served by one district judge.” Devlin concludes that “the rural space is conducive to erasing crimes of sexual violence.”

Broadening and Correcting the Story of the Frontier

While Devlin’s work gives insight into this dynamic, it also helps to correct a romanticized version of frontier life. “We tend to focus on the heroic white male homesteader who works tirelessly to make something of himself, supported by a pious wife who came out here grudgingly, but does what she has to do for her family.” In fact, family life was not untroubled during the settlement of the Great Plains. Besides cases of rape, incest, statutory rape, domestic abuse, etc., court records testify to “divorces, child custody cases, and hearings to consign orphans and vagrant children to industrial schools or convents.” Women’s aspirations were also more varied; Devlin has often seen court records of “suits brought by female business owners.”

“History is life,” Devlin said, adding that a full account of life yields more than “‘his story’ but also more than ‘her story.’” For Devlin, the first two letters of the word “history” stand for “human interest.” History preserves a record of human decision-making, and in studying all those involved in the human story, “you see what other people have done over the course of time and you get to discuss instances when decisions were perhaps not the best or, on the other side, were the best options available.”

She will bring this perspective to her new post as Assistant Professor of American History and Government at Sterling College, a small liberal arts school in Kansas founded in the 1880s. Although “a great institution,” the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, with its student population of around 25,000, was often “overwhelming” for Devlin, especially at first. Prior to graduate school, she spent a decade teaching social studies to grades 7-12 at Smith Center High School in northcentral Kansas. She saw her students over the course of many years as they advanced from seventh grade to their senior year, and she continues to interact with many of them as they have gone on to build their own lives. “I look forward to getting back to a space where I truly get to know the students and can get involved in their futures.”

When not helping students, Devlin researches a range of topics related to the legal history of the Great Plains. She also plans to apply for grants to fund the digital preservation of the records contained in the rural courthouses of her region—and of the multitude of untold stories they contain.