Who Lost China?

After the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, American politicians immediately engaged in a blame game that was rooted in their fear of monolithic communism.

China: A Cautionary Tale

Shortly after assuming the presidency, President Lyndon Johnson granted an interview to Jack Knight of the Knight-Ridder newspaper chain. In the interview Johnson surprised the newsman by posing his own question: “What do you think we should do in Vietnam?” The new president was beginning to confront a challenge that would haunt his presidency. A recent coup in South Vietnam had destabilized the situation, leaving the new Democratic President in what he feared was a no-win position. He outlined his options for Knight. “There’s only three things you can do,” Johnson said. “One is to run” from the conflict “and let the dominoes start falling over. And, God Almighty, what they said about us leaving China would be just warming up compared to what they’d say now.”

LBJ did not clarify who he meant by “us” when he expressed his fears to Jack Knight. Was he referring to the United States or the Democratic Party—or both? Indeed, he was thinking of a foreign policy debate that began in 1949 and continues today in scholarly circles. The debate was framed as a simple question: Who lost China? A shrewd politician like Lyndon Johnson considered the likely political ramifications of his foreign policy decisions, drawing on hard lessons he and other politicians learned in their careers. Johnson did not want his decisions on Vietnam to doom his presidency.

The Chinese Civil War Ends

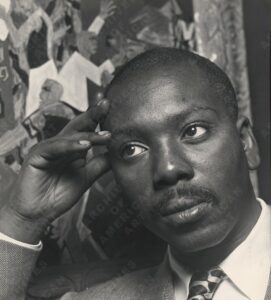

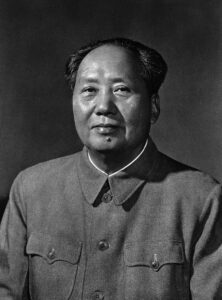

The question—Who Lost China?—refers to the long Chinese Civil War finally won by the Chinese Communist Party in 1949. The United States had supported the Chinese Nationalist Party known as the Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang’s war against the communists, led by Mao Zedong, was on hold during WWII. The two sides turned their weapons from each other toward the Japanese invaders—although not as aggressively as either side claimed or as aggressively as the Allies wanted.

Mao officially proclaimed the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and Chiang relocated the remnants of his government and military forces to Taiwan (Formosa) that same year. Chiang insisted that he remained the rightful ruler of China—a position the US endorsed. It did so because in the early Cold War years US foreign policy rested on at least three assumptions: communism was monolithic; it was bent on world domination; and once one nation “was lost” to the communists, its neighbors would inevitably follow, like dominoes stacked in a line. The year 1949 was a frightening year for Americans holding these assumptions. In May, the Berlin blockade ended, following a massive and heroic airlift that since June of 1948 had supplied basic necessities to the people of West Berlin. Yet in August, the USSR successfully tested an atomic bomb, thus ending the US nuclear monopoly, and by October, the Chinese Communist Party had defeated its US-backed rival. The communists now had control of the largest country on earth.

The American Blame Game

The loss of China blame game endured into the 1960s, for three primary reasons. First, China was viewed as capable of projecting its power and influence throughout Asia, doubling the communist threat already posed by the Soviet Union. Second, Senator Joseph McCarthy heightened fears of Communist China in his demagogic campaign against Americans he accused of collaborating with Communist powers. Third, in part because of McCarthy and the movement— McCarthyism—he spawned, the communist fate of China proved an effective theme for other politicians.

During the early years of the Cold War, many American policymakers classified the world’s nations into one of three groups: capitalistic democracies, communist dictatorships, and countries that America had to protect from communist aggression. In the contest between capitalism and communism, they viewed any nation not already committed to one system or the other as pawns on a chessboard. They should pick the pawns worth saving, then, in so far as possible, move them to their advantage. Many policymakers did not question the hubris behind this assumption of American invincibility until the war in Vietnam grew into a long, costly failure.

American Fears of Monolithic Communism

Nor did most Americans, during the early years of the cold war, question the assumptions they held about communism. They saw Communism as monolithic—“a large, powerful, and intractably indivisible and uniform movement”—hell-bent on world domination. And if it was capable of creeping ever closer to the US mainland, then Americans had reason to be frightened. Joe McCarthy played on these fears when he accused Asian experts in the US State Department—the so-called China hands—of undermining or betraying US interests in Asia. His crusade against communism contributed not only to an atmosphere of fear but, for a few years, to the silencing of any dissent that might lead Americans to re-think their strategic approach to communism.

McCarthy and his Republican Senate colleagues, Richard Nixon and Barry Goldwater, used their anti-communist crusade as an effective wedge issue by challenging the Truman administration’s Korean War strategy and their failure to save China from the communists. Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson organized one notable attempt to answer the administration’s critics. Acheson instructed his department to compile a detailed history of US policy toward China. Totaling over one thousand pages, the China White Paper, as it came to be known, was an attempt to educate the public on why the communists won China. Many mocked Acheson’s efforts as an elaborate attempt to cover up administrative malfeasance. Columnist Joseph Alsop captured the attitude of Acheson’s critics, saying; “If you have kicked a drowning friend briskly in the face as he sank for the second and third times, you cannot later explain that he was doomed anyway because he was such a bad swimmer.”

There were Americans who saw it differently. In an editorial answering the Truman administration’s critics, the Washington Post questioned the idea “that China was a sort of political dependency of the United States to be retained or given away to Moscow by a single administrative decision taken in Washington. It was not. China was—and still is—a vast continental land, diverse and disunited, peopled by some half a billion human beings—most of them living at a level of bare subsistence, immemorially exploited by landlords and harassed by warlords, in the throes of revolutionary pressures and counter-pressures that have been felt the world over. The United States has never at any time been in a position to exercise more than a minor influence on China’s destiny. China was lost by the Chinese.”

Teaching the “Who Lost China?” Debate

In researching this topic, I stumbled into a lesson posted on the Harry Truman Presidential Library and Museum website. The lesson includes primary sources students can read, proposing their own answers to the question, Who lost China? “These questions are not unique to this time period,” the lesson’s background author argues. “While engaging in an active foreign policy after World War II, United States’ leaders have faced difficult choices. Can the United States pick sides in a conflict with no ideal partner? What were the risks of not picking a side? Is the United States even capable of influencing the outcome of foreign conflicts? These questions ring as true today as they did in 1950.”