William McKinley and the First Modern Presidential Election

This week we’re marking the 125th anniversary of the presidential election season of 1896. In this groundbreaking year, both parties’ candidates deviated from past campaign practices, writes John Giltner, a 2018 graduate of the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program. Giltner, whose thesis covered the contest between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan, credits McKinley with fundamentally reshaping American presidential elections.

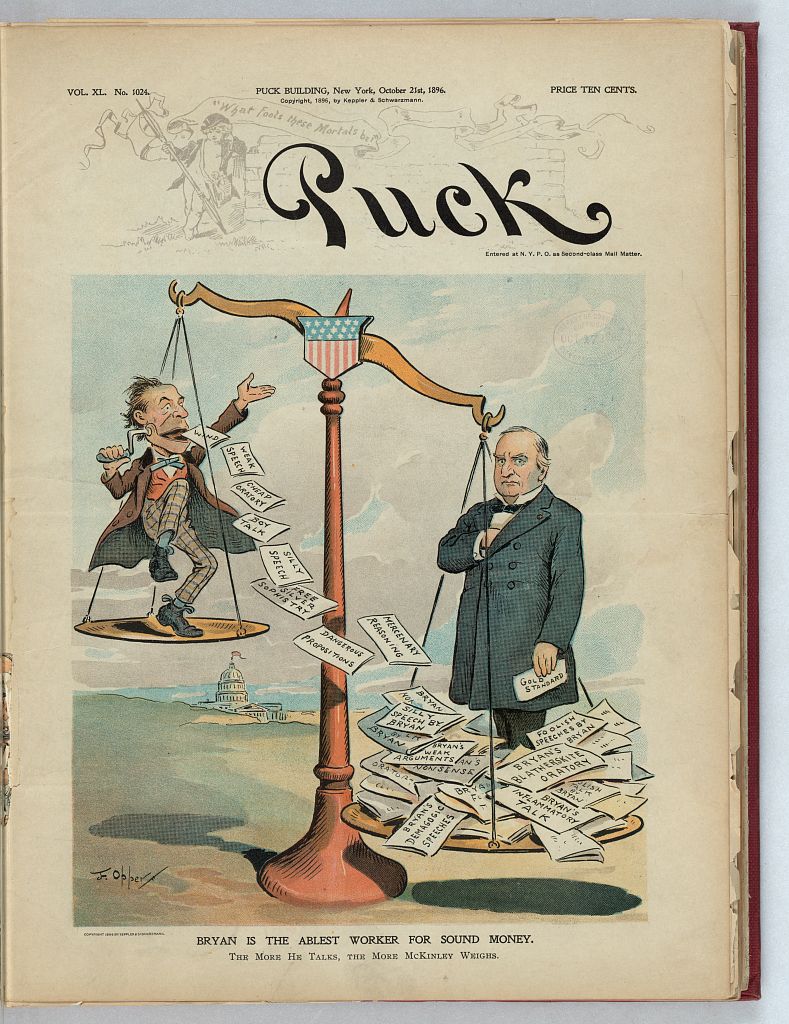

A long-held general misconception of William McKinley saw him as a weak leader and a puppet of the Big Trusts of the East. Another misconception held that McKinley was elected in 1896 because of money – that John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and the other titans bought the election. As a result, William McKinley was relegated to a footnote in history, with just brief mentions in today’s high school textbooks. A more careful and fair assessment shows William McKinley to be the first modern presidential candidate and his campaign in 1896 the first modern presidential campaign.

Prior to the 1896 campaign, candidates placed themselves in the “hands of friends”, letting close surrogates run their campaigns while maintaining a low profile. Candidates rarely spoke publicly, other than in whatever official capacity they currently occupied, leaving their managers to garner support for their candidacies shortly before the state conventions held in the election year itself. Aside from the 1892 convention, when there was an incumbent running, no GOP convention since 1872 had been decided on the first ballot. However, until McKinley, no other candidate had seen the value in locking up support at these state conventions. The result was a multitude of favorite son candidates and various backroom deals to settle on a nominee. McKinley saw these conventions differently, as the de facto primaries of that day and a battlefield that needed to be won if he had any hope of being President.[1]

The front line of McKinley’s efforts to win the nomination were “traveling salesmen.” These were, just as it sounds, men who worked in the sales field, selling everything from Fuller Brushes to machine parts and other goods. Shop keepers, business executives, and other small business owners who were also local Republican Party delegates, these salesmen were paid by the campaign to talk up McKinley and build support for his candidacy in the course of their regular sales calls.

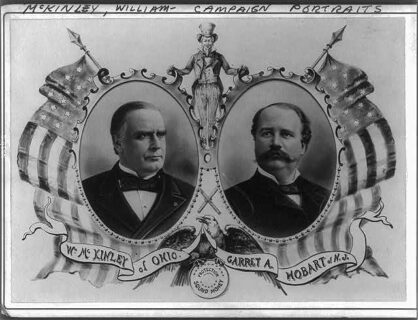

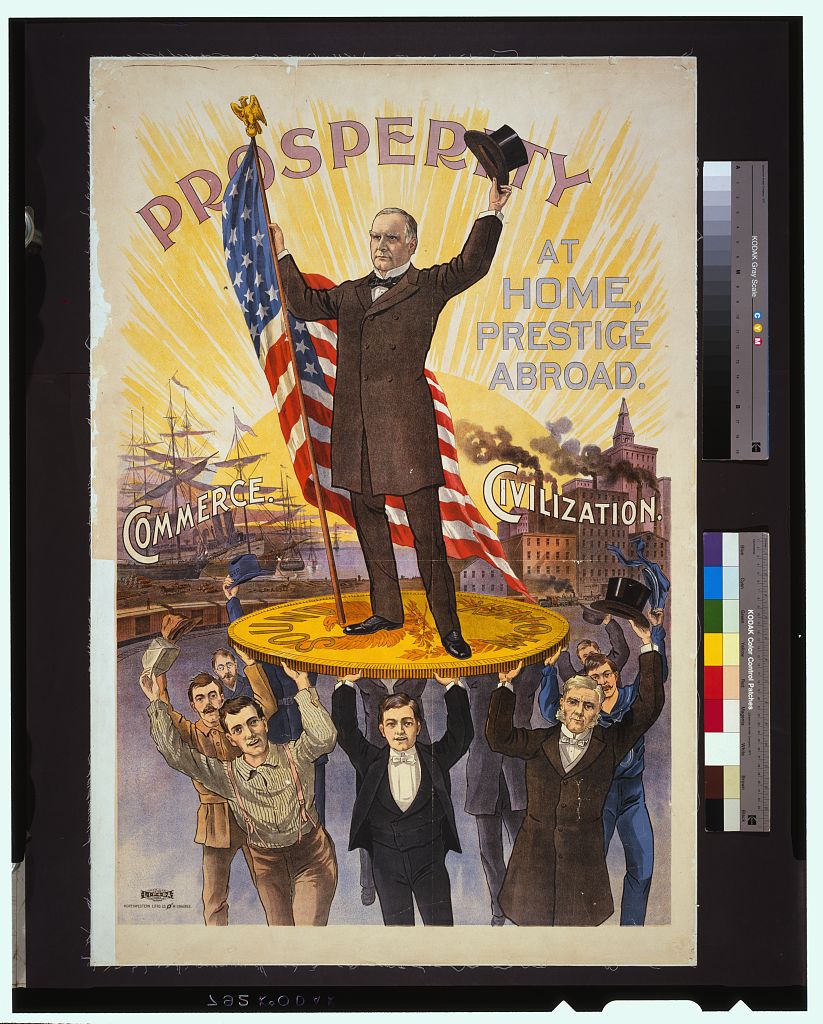

The McKinley campaign also hired Perry Heath to coordinate, print, and distribute a direct mail operation. Heath’s operation produced in excess of 120 million copies of 275 different pamphlets that were shipped to state and local Republican organizations around the country. The pamphlets were produced in several different languages, including English, German, Yiddish, Spanish, Italian, French, and Dutch. In addition to pamphlets, the campaign produced newspaper articles for mass distribution in friendly newspapers across the country, keeping the campaign’s unified message of Sound Money. According to its last financial statement, the campaign spent $469,000 on printing alone.[2]The Chicago office also produced materials to be used in local campaign events. One example was a booklet called “Republican Campaign Glees”, a song book that was sold in Richmond, Indiana for 10 cents. It contained such songs as “McKinley,” sung to the tune of “America,” and “McKinley and Hobart Forever,” to the tune of “Marching Through Georgia.” On the back of the book was an advertisement from a local jeweler, offering McKinley spoons for $1.50.[3] Finally, the campaign hired William H. Hahn to run the Speaker’s Bureau of Republican officials to speak on McKinley’s behalf; and in a stroke of genius, Hahn also employed many foreign language speakers to secure the immigrant vote.[4]

The opposing party, the Democrats, were in shambles, torn by conflicting stances on the gold standard. What sparked this war within the Democratic Party was, for the most part, the sharp decline of gold reserves in the Treasury, which had dropped below the acceptable level of $100 million. By the time of the election of 1896, the Democrats were solidly divided into two camps. One argued that a gold-only standard was bad for the country because the limited supply of gold would mean far too little currency in circulation, driving down prices for farm goods. The other side favored staying on the gold standard, arguing that bimetallism would have disastrous inflationary effects and would hurt industry.[5] This division translated into a slew of candidates for the Democratic nomination in 1896.

Enter William Jennings Bryan, just thirty-six years old, a former Congressman who was decidedly pro-silver. While no one seriously considered him a candidate, between 1894 and 1896 he began canvassing the nation, much like McKinley did, courting delegates. He was an extremely well-liked speaker and became known as the “Boy Orator from the Platte River Valley.” According to R. Hal Williams, “Unlike McKinley, Bryan drew on the Jeffersonian tradition of rural virtue, suspicious of urban and industrial growth, distrust of central authority, and abiding faith in the powers of human reason.”[6] A classic Jeffersonian-Hamiltonian battle was being set up for the general election in 1896, with McKinley harkening back to Hamilton’s views on protective tariffs and a manufacturing based economy. But Bryan would have to get the nomination first.

The “favorite son” candidate of the Resolutions Committee at the Democratic convention was Senator Benjamin Tillman. Tillman wanted to speak first on the evening Bryan was asked to speak, leaving the young Nebraskan to close. In a slow, conversational tone, Bryan argued the importance of free silver. As he built momentum he called the free silver issue “the cause of humanity” and said its outcome depended on “a contest of principles.” Bryan had the audience hanging on every word, finishing with the now famous line “You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold.”[7] As he delivered the line, Bryan stretched his arms out like Christ. He then dropped his chin and walked off the stage to what was described as a “fearful silence.”[8]

William McKinley had never planned to take the stump when running for President. As mentioned, this had not been the custom in previous contests. Candidates would stay in their hometowns, giving occasional speeches and interviews, attempting to stay above the fray and appear “presidential.” William Jennings Bryan changed that, developing his own campaign innovation. He engaged in the first whistle-stop tour in American politics. Over the course of the campaign, historians calculate, he gave over 570 speeches and covered 18,000 miles by rail. He spoke on average 80,000 words a day. McKinley knew he could not match this effort.[9] A different plan had to be enacted, and the Front Porch Campaign was born.

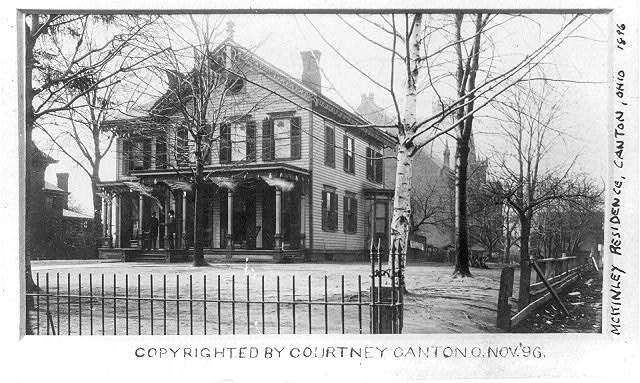

When McKinley’s term as governor was drawing to a close, he and his wife had to decide where they wanted to live. As luck would have it, the home they rented at the beginning of their marriage on North Market Street in Canton, Ohio had come available. During the campaign it was widely assumed that this was McKinley’s long-time home. In reality, the McKinleys lived in a small set of rooms at the back of the house, with the rest converted into office space for the campaign. Carolyn Herrick, wife of Cleveland industrialist and campaign advisor Myron Herrick, staged some of the McKinley’s personal items to keep up the illusion that this was their long-time home.

The genius of the Front Porch campaign was that on the surface it did not resemble a campaign at all. Supporters had already begun showing up at McKinley’s door, so why not make the most of it? The campaign could invite groups it wanted, those that represented key voting blocs such as labor or German-Americans. McKinley could deliver ready-made remarks and would control his message. Bryan was already wearing himself out on his whistle-stop tour, giving the same speech a dozen or more times a day. By staying at home, McKinley would be playing to one of his biggest strengths – his discipline. Also, Canton was on several major rail lines with easy connections throughout the Midwest, Mid-Atlantic, and Border States. [10]

As William Harpine pointed out, “a presidential candidate in 1896 could speak in person only to a small portion of the electorate, but technology could spread the candidate’s word across the land in short order.” What developed in Canton during the summer and fall of 1896 was a series of carefully-organized staged incidents.[11] When a group wrote that they would like to visit Canton, the campaign would request that a spokesman from the delegation visit ahead of time to discuss the matter. At the meeting McKinley would ask what the spokesman intended to say. McKinley would edit the remarks as needed and craft an appropriate response that also weaved in the themes of the campaign – currency, protection, and patriotism.[12] The event would always start off the same, with the delegation being met at the train station by the Home Guards, a group of mounted volunteers who would escort the visitors up Market Street, often with a band. The route would be decorated with bunting and flags and townspeople would turn out for the spectacle. Arriving at McKinley’s home at the prearranged time, the group would wait for McKinley to emerge onto the porch. The group’s spokesman would deliver his remarks and McKinley would respond from his prewritten script. Joseph P. Smith would transcribe the candidate’s words and distribute them to the press.[13]

The Front Porch Campaign thus became an industrial operation. By Election Day, over 750,000 people had visited Canton, nearly one out of every twenty voters. Thanks to the support of the railroads, ticket prices were slashed. The Boston Herald organized a “Pilgrimage of Sound Money Men” trip to Canton, a four day excursion that cost each pilgrim just $28, including meals and sleeping cars.[14] The campaign also became big business locally. The Hurford House Hotel, for example, ran full page ads in The Canton Morning Record, billing itself as the premier hotel for those visiting McKinley and calling Canton a “Presidential town.”[15] The Evening Repository in Canton would print daily summaries of the groups that visited McKinley as well as the upcoming schedule for the next day. In late October, the Front-Porch Campaign reached its peak. The growing crowds that filled Canton from countless railcars gave the message that the outcome of the election was no longer in doubt.

William McKinley won the election of 1896 with 271 Electoral College votes, 47 more than needed. He garnered 51% of the popular vote, the highest percentage since Grant’s reelection and over 2 million more than Harrison received in 1892. He carried every battleground state and every state in the critical central Midwest, and took New England by 2-1 ratio.[16] The election of 1896 not only was a realigning election, ushering in a new era of Republican control of Washington for almost all of the next 35 years; it also redefined how campaigns are run and won. From now on, the power of the party bosses over nominations to the presidency would be greatly diminished. The general elections would now be more about the candidate, not the party

Sources

Rove, Karl. The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Republican Glees, Songs Copyright J.M. Coe, Richmond, Indiana, 1896.

Horner, William T. Ohio’s Kingmaker: Mark Hanna Man and Myth. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

Williams, R. Hal. Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2010.

Merry, Robert W. President McKinley Architect of the American Century. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Harpine, William D. From the Front Porch to the Front Page: McKinley & Bryan in the 1896 Presidential Campaign.College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

Advertisement “Pilgrimage of Sound Money Men to Canton, Ohio”, Boston Herald, October 8, 1896, the McKinley Collection, William McKinley Presidential Library, Canton, Ohio.

Advertisement, “The Hurford House”, The Canton Morning Record, October 8, 1896.

William Jennings Bryan, Delivered at the Democratic National Convention, Chicago, IL, July, 1896.