WWI and the 1920s: Interview with Jennifer Keene, Part 1

Teaching American History has recently published World War I and the 1920s: Core Documents, a collection curated by Professor Jennifer D. Keene, Professor of History and Dean of the Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at Chapman University. Keene, a specialist in American military experience during World War I, has published three studies of this subject, along with numerous essays, journal articles, and encyclopedia entries. Keene also edited our collection of core documents on World War II (2018; 2nd ed. 2022) and teaches courses on the World Wars and Modern America for the Master of Arts in American History and Government program at Ashland University.

- 1. For Europeans, World War I was devastating. Technological advances in weaponry made combat terrible and costly to life and well-being. Many grew pessimistic about modern “progress.” To Americans, the war brought risk, loss and sacrifice, but did not diminish expectations for economic growth and social and political reforms. What accounts for the difference between the European and American experience?

Although it’s true that Americans were less devastated by the experience of World War I, the war brought profound changes to American life. We entered the war late and suffered fewer battlefield deaths than the Europeans over the course of our year and a half involvement. However, Americans of that era saw the war as the major historical event of their lifetimes, one that changed everything. It changed the role of the United States in global politics and gave it a stronger position in the global economy. It accelerated the fight for women’s suffrage. It changed African Americans’ understanding of their own prospects in our society, laying the groundwork for the modern Civil Rights movement. We also make a big mistake if we ignore the long-term effect of Wilsonian rhetoric on the way Americans understand their civic responsibilities and role in the world.

The momentum of the Progressive movement propelled America into the war and shaped Americans’ expectations. When the European war began in 1914, Woodrow Wilson based his argument for neutrality (Document 1) on the claim that neutrality would allow the United States to arbitrate between the warring sides. In April, 1917, after concluding that Germany represented a national security risk and could be defeated only if America joined the fight, Wilson delivered a war address (Document 6) that distinguished America’s war aims from those the other combatants. While others waged a territorial contest, Americans would fight to remake the international order in the image of liberal democracy. This would help the world powers negotiate their differences, preventing future wars. Fast forward to Wilson’s Fourteen Points (Document 14), and you see him approaching a negotiated settlement in a progressive manner. He first convened a group of academic experts on the contested regions of the world, “The Inquiry,” to draft his proposals. He thought he could sit down with these experts to redraw the map of Europe, rationally solving old historic conflicts that nobody else had been able to solve.

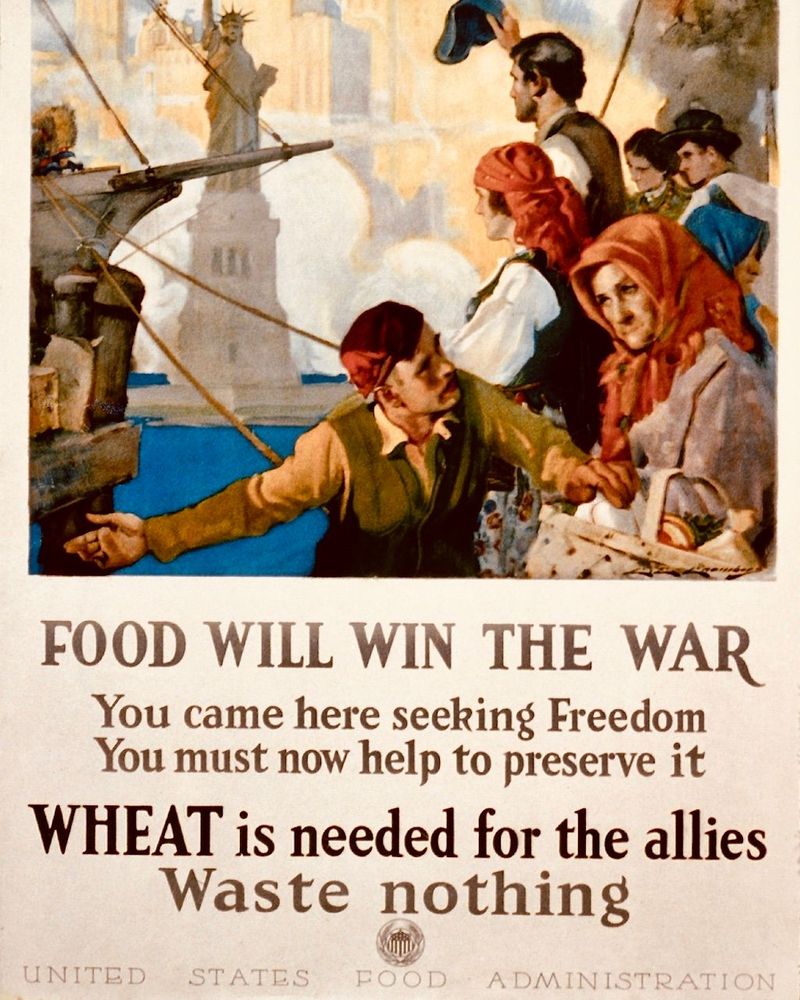

Others acted from the same progressive impulse. As Director of the US Food Administration, Herbert Hoover could have confiscated food sources and rationed them. Instead, he asked for voluntary efforts from across American society (Document 13), as he had when he headed the Commission for Relief in Belgium. To support the war effort, he asked people to voluntarily conserve food. This progressive approach left a legacy, influencing the conduct of agency heads during the mobilization for World War II.

Of course, Wilson’s reformist impulses were inconsistent. After arguing that America needed to make the world safe for democracy, he asked Congress to pass an Espionage Act that criminalized public dissent and obstruction of conscription under the new Selective Service Act. For the most part, Americans went along with this. Immediately after the war, the Supreme Court affirmed the suppression of dissent in Schenck v. United States (Document 19), ruling that freedom of speech is not an unconditional right.

- 2. Given Wilson’s intolerance of dissent, why did he change his position on women’s suffrage?

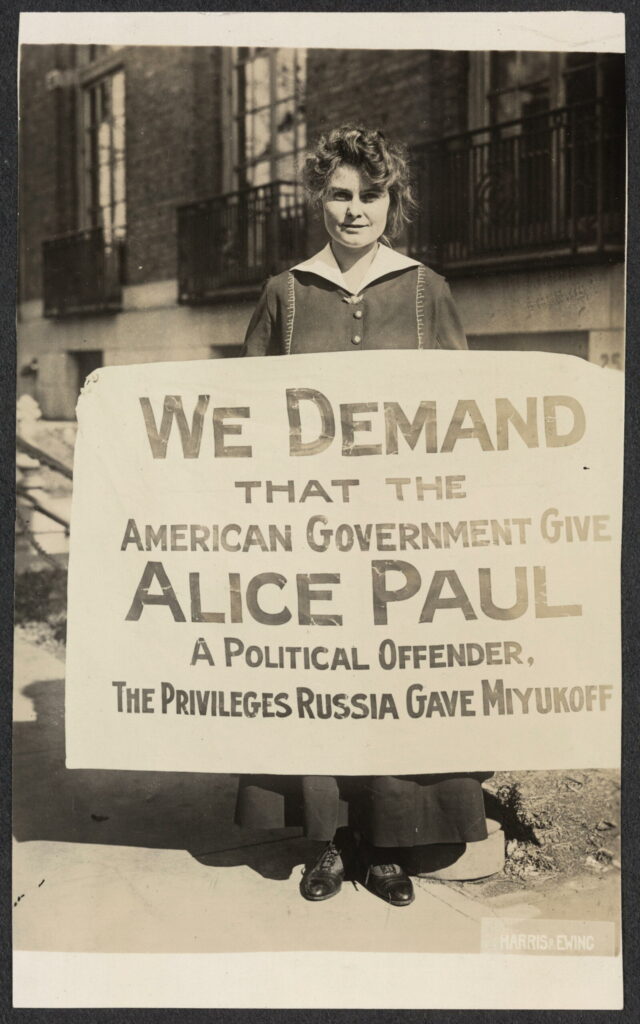

The suffrage activists forced Wilson’s hand. By 1917, the suffrage movement had divided into two main groups, each pursuing different strategies, yet it took both groups to force the change. Carrie Chapman Catt of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA; see Document 12) pressed for a federal woman suffrage amendment while seeking simultaneously to secure women’s suffrage one state at a time, by persuading states to change their own constitutions . She wanted Wilson to endorse the national movement, and use his position as head of the Democratic Party to move a proposed amendment through Congress. Catt realized she could exert pressure on Wilson by encouraging women to support the war through public volunteer efforts. “How can you ask women to assume the responsibilities of citizenship,” she asked in effect, “without according them the rights of citizens?” Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party (NWP; see Document 10) pushed more aggressively for an amendment to the federal constitution. They began picketing the White House in January 1917. No one had ever done that before. They continued after America entered the war in April, calling Wilson a hypocrite for pushing a war to safeguard democracy abroad while denying women democratic rights at home. As upper and upper middle-class women, they could use their social connections to publicize their brutal treatment in prison when they were arrested for blocking the sidewalk in front of the White House.

This negative publicity put Wilson in an embarrassing position. Meanwhile, Chapman’s state-by-state strategy made a significant gain when the state of New York voted for women’s suffrage in November 1917. Women’s exercise of voting rights in key states like New York might derail Wilson’s legislative agenda or Democrats’ chances in upcoming elections. Wilson had only squeaked by in the 1916 presidential election. Still, when Wilson endorsed giving women the vote on September 30, 1918, those in the movement remained dissatisfied; they wanted him to push the amendment through Congress. In the end, the 19th amendment was approved by Congress after the war ended and ratified by a sufficient number of states when a single Tennessee state legislator changed his mind.

African Americans also protested the hypocrisy of a war for democracy abroad while democratic rights and protections were denied to Blacks at home (see document 20, “Returning Soldiers” by W. E. B. Dubois), but they didn’t have the same success. Wilson did nothing to combat the epidemic of racial violence that erupted in 1919 after the soldiers returned home.

- 3. During the war, government leaders used the media to rally public support. One sees this in Hoover’s use of propaganda to save food and in the posters encouraging enlistment and purchase of war bonds. Even private groups hoped to shape behavior through advertising. African Americans published advice to Southern Blacks on how to behave after migrating North (Document 22). The Sears Roebuck catalogue advertised modular home kits (Document 34). Was this a new feature of American life?

Wartime leaders always aim for unity on the home front, but Wilson faced a particular challenge. He couldn’t point to a direct attack on the US such as that at Pearl Harbor. His war address began with circumstantial evidence of the security threat, but this fell flat in the rural South, West and Midwest where populist feelings remained strong. Many said, “This is a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight”—that America entered the war to ensure that loans to the allied nations would be repaid and that American manufacturers would make nice war profits.

To solve this problem, Wilson created the first federally controlled propaganda organization, the Committee on Public Information, that used Progressive propaganda techniques, previously employed to popularize social reforms, for government purposes.

The Wilson Administration also used legal and social pressure. While the Espionage and Sedition Acts threatened arrest for those who voiced opposition, community mobilization offered incentives to support the war effort. Women signed the food pledge because a local committee woman knocked on their door; people were asked at work to buy Liberty Bonds; and then they were issued cards testifying they had done these things to hang in their windows. Displaying these cards won you social approval. Not displaying them aroused suspicion—especially if you had a German surname. Once men were conscripted, many families had a personal stake in the success of the war effort and wanted their community to support the war.

- 4. So, Wilson’s effort to mobilize the country for war succeeded.

Remarkably well, I would say. The US entered the war with just 300,000 men in the military but grew that number to over 4 million, with 1.2 million men in overseas combat, in a year and a half. We also produced the food needed for those troops. That’s an amazing success.

Did the war, as Wilson promised, spread democracy? No, but as often in US history, the aspirations of the period continued to animate activism and policy after the war. Of course, Americans wondered in hindsight whether entering the war was a mistake, especially when war clouds gathered once again in Europe. They then looked to the steps that led to entering WWI in an effort to learn from the past. Just as it took two and a half years for us to get involved in World War I, it took two and a half years for us to enter World War II – reflecting Americans’ mixed feelings about intervening in European conflicts. Even today, Americans debate whether and how to use our power overseas so as to balance our self-interest with our idealistic goals for the world at large.