World War I and the 1920s

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife as they made a state visit to Sarajevo, Bosnia. Princip acted on behalf of the Serbian-based Black Hand terrorist group which sought independence for Bosnia, a recently annexed imperial province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His desire to see Bosnia united with Serbia eventually came true when the nation of Yugoslavia was founded in 1918. By then, Princip had died in prison, one of countless lives lost during the brutal four-year world war that the assassination triggered.

In the wake of Ferdinand’s death, five weeks of indecision ensued. A flurry of increasingly bellicose telegram exchanges among European leaders, heated internal governmental debates, and militaries put on high alert quickly turned a regional dispute into a crisis that threatened the entire European continent. By early August, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Germany had decided that this was the moment to resolve long-simmering territorial disputes with a quick, decisive war. Their decision for war had grave implications for Serbia, Belgium, France, and Great Britain (and their empires), all quickly pulled into the fray. World War I had begun.

Across the Atlantic, President Woodrow Wilson immediately declared the United States neutral in the conflict and urged Americans to remain “impartial in thought as well as action” (See Declaration of Neutrality). Over the next few months, hopes for a short war evaporated amid staggering casualties. On the Eastern Front, Russian and German armies traded huge swaths of land at great cost without producing the expected victory. Along the Western Front, the massive trench defensive system taking shape created a stalemate. In early 1915, as armies regrouped, Great Britain and Germany turned their attention to the seas, hoping to use naval power to bring their enemies to the negotiating table. Britain relied on its naval superiority to create blockades that prevented goods from reaching the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire). Germany turned to a new weapon, the U-boat, or submarine, to sink cargo, troop, and eventually passenger ships traveling into the war zone.

The popular song “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” reflected Americans’ general desire to remain on the sidelines of the expanding war. Nonetheless, the conflict increasingly touched the nation. U.S. banks financed a booming trade with the Allies (the British Empire, France, Belgium, Russia, and Italy), which included arms and munitions. Britain had been the nation’s largest prewar trading partner, and now purchased nearly 65 percent of U.S. exports. By contrast, trade with Germany declined considerably, reflecting Americans’ pro-Allied sympathies and an effective British blockade that limited access to German ports. In response, Germany tried to disrupt shipments from the United States with a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. This decision backfired with the torpedoing and sinking of a British passenger ship, the RMS Lusitania, on May 7, 1915 (See Enlist). The attack killed 1,198 passengers, including women and children, and coincided with the release of an official British report detailing atrocities committed by German troops when they invaded Belgium in 1914. These incidents catalyzed anti-German feelings within the United States.

Wilson shied away from entering the war in 1915 and 1916. His rhetoric, however, increasingly lambasted Germany for killing noncombatants and illegally interfering with the rights of neutral nations to use the seas unmolested. In the wake of another controversial sinking that resulted in civilian deaths, he warned Germany that a continuation of unrestricted submarine warfare would result in a break of diplomatic relations with the United States (See Response to German Submarine Warfare). Relations briefly improved when Germany pledged restraint, but in January 1917 Germany decided that victory was within reach if its U-boats could cut the supply lines between the Allies and the United States. Anticipating that the United States was likely to declare war once unrestricted submarine warfare resumed, the German foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, took a gamble and tried to secretly entice Mexico into attacking the United States along their common border. The interception and publication of the Zimmermann Telegram further damaged relations between the United States and Germany.

Finally, on April 2, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, declaring that the “world must be made safe for democracy”. Congress actively debated Wilson’s request, and several legislators, including Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska, voiced doubts about going to war (See Opposition to War). Dissent became harder once the decision for war was made.

The United States officially declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. Entering the war as an “associate” power, the United States cooperated with the Allies but also remained free to pursue its own strategic and foreign policy objectives. Wilson did not request a declaration of war against Austria-Hungary until December, and did so then to prevent Italy from leaving the Allied coalition after catastrophic losses in the Battle of Caporetto. The United States was never at war with the Ottoman Empire or Bulgaria.

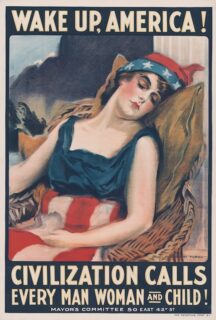

To raise the bulk of the wartime force, the nation turned to conscription. Uncertain how the public would react, the newly formed Committee on Public Information organized a massive propaganda campaign to promote military service as a citizen’s patriotic duty (See Recruitment Poster). New laws also established stiff penalties for interfering with the draft.

The 1917 Espionage Act made it illegal to aid the enemy, encourage mutiny, or interfere with military recruitment. A year later, the 1918 Sedition Act expanded the range of prohibited acts by criminalizing “abusive or disloyal language” about the flag, Constitution, government, or armed forces. Ignoring these wartime restrictions on civil liberties, the Socialist Party mailed an antidraft circular to men who had registered for the draft (See Wake up America!). Socialist Party secretary Charles T. Schenck appealed his conviction for violating the Espionage Act all the way to the Supreme Court. The resulting Schenck v. United States decision upheld the law’s constitutionality, agreeing that during wartime Congress had the authority to limit speech deemed to pose a “clear and present danger”. This landmark decision was the Court’s first significant ruling on the extent and parameters of the right to free speech.

Overall, the draft operated successfully to raise the wartime force. Twenty-four million men registered, and the army grew from a peacetime force of approximately 300,000 to nearly 4 million men, of whom 72 percent were drafted. However, a sizable number dodged the draft. Three million men, representing 11 percent of the draft-eligible male population, either failed to register or did not report for service when called.

The new army reflected the diversity of the U.S. population. One in five was foreign-born (100,000 did not speak English) and 13 percent were Black, even though African Americans were only 10 percent of the entire population. Nearly 25 percent of eligible male Native Americans served, the largest proportion of any single racial or ethnic group.

Mobilizing the economy posed another significant challenge. The Food Administration organized its own massive propaganda campaign around the slogan “Food Will Win the War,” emphasizing America’s vital economic role in supporting the Allied war effort (See Food Will Win the War). Patriotic messages also encouraged women to volunteer or seek paid employment in war-related jobs to do their part for victory (See Letters from a Working Wife).

Wilson’s emphasis on spreading democracy globally had some unintended effects at home, notably by energizing the female suffrage and Black civil rights movements. The two dominant female suffrage organizations reacted to the war differently. Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), urged members to serve on local, state, and national committees selling war bonds, promoting food conservation, and providing troops with care packages. Pointing to these demonstrations of women voluntarily performing their patriotic civic duties, Catt called upon Wilson and Congress to support female suffrage in return (See Open Address to the U.S. Congress). By contrast, the National Woman’s Party picketed the White House with signs denouncing Wilson for his failure to extend democracy to American women. When arrested, they conducted hunger strikes that garnered public sympathy, further embarrassing the president (See Alice Paul in Prison). Both strategies had an impact, and in 1918 Wilson became the first sitting president to endorse female suffrage. Two years later, the Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited denying citizens the right to vote based on sex, was ratified.

The civil rights movement had less success. In 1918, civil rights activist and scholar W. E. B. Du Bois urged African Americans to “forget our special grievances” and close ranks with “our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy” (See Close Ranks). Du Bois’s stance was controversial. Racial discrimination and racially motivated violence, including lynching and race riots, continued unabated throughout the war. During the Great Migration, nearly half a million African Americans sought a better future by moving north and leaving the Jim Crow South behind. They escaped legalized segregation, but not racial prejudice. Black northerners offered advice to help the newcomers prosper and avoid racial violence—instructions that also revealed class and regional tensions within the Black community (See Navigating the North).

Wilson’s desire to spread democracy depended first and foremost on the Allies winning the war, a victory by no means assured. In November 1917, a Bolshevik government took control of the Russian Revolution and opened peace talks with Germany. A separate peace between Russia and Germany would allow Germany to funnel additional troops to the Western Front, where it might potentially defeat France and Britain before the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) arrived. The Bolsheviks also published secret treaties that described how the Allies expected to divide acquired territories once the Central Powers were defeated. These revelations raised doubts about the true purpose of the war. In response, Wilson announced the Fourteen Points, providing details of a proposed peace settlement that he hoped would end conflict permanently in Europe (See The Fourteen Points). Russia still left the war, but the Fourteen Points renewed hopes for a better world if the Allies prevailed.

Wilson knew that having a decisive voice in determining the peace depended on a strong showing by the AEF on the battlefield. It took nearly a year to organize, train, and transport an American force capable of fighting overseas. The AEF finally entered the fray in the spring and summer of 1918. Fighting alongside the Allies, American forces helped stem and turn back a series of German offensives that brought the German army within striking distance of Paris. By September, the AEF was ready to launch American-commanded operations from its own sector of the Western Front as part of a coordinated Allied offensive. The AEF fought the Saint-Mihiel Offensive (September 12–16) and then on September 26 opened the historic Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a campaign that lasted for forty-seven days until the Armistice was signed on November 11. Lieutenant Colonel Ashby Williams documented the terror of enduring artillery barrages and combat during the Meuse-Argonne, one of the bloodiest battles in U.S. history (See Fighting in World War I).

Realizing that the AEF would only become stronger in the coming year, Germany requested an armistice based on the Fourteen Points before any Allied soldiers had set foot on German soil. The United States made a vital contribution to the Allied coalition victory but paid a steep price. The AEF suffered 320,518 casualties (204,002 wounded and 116,516 deaths), including 53,402 killed in battle.

Sergeant Charles R. Isum was wounded a day before the Armistice went into effect on November 11, 1918, while serving in the 92nd Division, one of two segregated combatant divisions reserved for Black troops. His most trying and demoralizing experiences, however, occurred not in combat but within the American army, where he encountered vicious racial prejudice (See A Black Soldiers Experience in France). Du Bois captured the disillusionment and combative spirit of men like Isum in his editorial “Returning Soldiers,” predicting that these veterans would transform the civil rights movement.

The laying down of arms along the Western Front was only the first step in a protracted peace process. President Wilson traveled to Paris to negotiate the peace terms with other Allied leaders (German representatives were excluded). The resulting Versailles Peace Treaty required Germany to accept responsibility for starting the war, disarm, and pay reparations for damages inflicted on the Allied nations. The treaty also created the League of Nations, a collective security organization charged with fostering international cooperation to mediate conflicts and tackle global problems. Collectively, the Paris Peace Treaties (which included individual treaties with each Central Power) dismembered the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires, replacing them with new nation-states in a redrawn map of Central and Eastern Europe. The Allies also became “trustees” of territories previously considered part of the Ottoman and German empires in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia under a new mandate system meant to prepare these areas for eventual independence. In fact, the mandate system allowed imperialism to continue and augmented the global influence of Britain and France.

Wilson was willing to accept the treaty’s flaws because he hoped that the proposed League of Nations would become a place where, over time, the worst excesses of the Paris Peace Treaties could be renegotiated. He first had to secure ratification of the Versailles Peace Treaty by the U.S. Senate. He faced stiff opposition from Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, who chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Lodge opposed the League of Nations, fearing a permanent commitment to defend member nations (See Opposing the League of Nations). Wilson undertook a cross-country speaking tour to counter Lodge’s claims (See Defending the Versailles Peace Treaty) and ruined his own health in the process. A stroke left Wilson debilitated, and during his absence from the national stage the Senate rejected the treaty. The United States subsequently concluded separate treaties to end hostilities with Germany, Austria, and Hungary, and never joined the League of Nations.

Wilsonian ideals, however, persisted past his presidency and into the Republican presidential administrations of the 1920s. In his 1921 address laying to rest the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery (See Laying to Rest an Unknown American Soldier), President Warren G. Harding used the occasion to open an international naval disarmament conference that resulted in several agreements. In 1928, President Calvin Coolidge negotiated the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which sixty-eight nations eventually signed, renouncing aggressive war as an instrument of national policy (See Renouncing War: The Kellogg-Briand Pact). Throughout the decade, American bankers also led efforts to renegotiate and restructure German reparations payments, including loans that helped fuel postwar economic recovery in Europe.

In the 1920 presidential campaign Harding promised a “return to normalcy,” a comforting slogan as Americans made the difficult, and sometimes violent, transition to peace. The immediate cancelation of wartime governmental contracts led to high unemployment and lower wages, prompting a wave of labor strikes. James Weldon Johnson dubbed the summer of 1919 “Red Summer” to describe the widespread racial violence, which included seventy-seven lynchings and twenty-five race riots, including one in Chicago where thousands of Black southerners had migrated. During this unstable period, the post office discovered thirty-four bombs addressed to prominent figures, and dynamite exploded outside the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who was convinced that a Bolshevik revolution was imminent within the United States (See The Case against the ‘Reds’).

Economic stability soon returned, and with it the desire to ensure that prosperity continued. Automobile manufacturer Henry Ford, who famously introduced the $5 a day paycheck in 1914, adopted a five-day workweek to create more jobs and improve productivity by reducing worker fatigue and turnover (See Henry Ford’s Five-Day Week). Installment payment plans increased consumers’ ability to purchase automobiles, appliances, and even homes. Sears, Roebuck and Co. marketed mail-order homes through its Modern Homes catalog, selling affordable prefabricated kits that, once assembled, transformed renters into suburban homeowners (See Mail Order Houses). Financier Jacob J. Raskob believed that average Americans could become rich through constructive investment in the stock market. Raskob had the misfortune of sharing his thoughts on the eve of the stock market crash in 1929, but his ideas foreshadowed modern-day investment practices (See Everybody Ought to Be Rich).

Prosperity in urban industrial areas camouflaged economic struggles in the agricultural sector, hardships that increased in the Great Depression. An urban/rural divide also shaped cultural conflicts of the 1920s, most notably debates over the teaching of evolution in public schools (See Debating Darwinism: “God and Evolution” and Debating Darwinism: “Evolution and Mr. Bryan”) and Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment (1919) prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors. In 1925, the North American Review featured arguments on both sides of the issue, showcasing the lack of consensus on whether the measure made society better or worse (See Prohibition: Success or Failure?).

Young women who behaved unconventionally, the “flappers,” emerged as another source of cultural anxiety in the 1920s. Flappers’ daring behavior thrilled some commentators and created moral outrage in others. One father’s concern about his rebellious “flapper” daughters revealed the generation gap at the root of this cultural conflict (See Me and My Flapper Daughters). Nonetheless, gender roles proved remarkably resilient once women got married and had children, as letters to Woman’s Home Companion on “My Everyday Problems” revealed.

The emergence of the “New Negro” heralded another critical cultural shift. In 1925, philosopher Alain Locke published an anthology that

announced the arrival of the Harlem Renaissance, an explosion of Black creative expression from artists, writers, activists, and musicians celebrating the distinctiveness of Black culture (See Enter the New Negro). The Harlem Renaissance explored empowerment through racial pride, the daily humiliations of racial prejudice, the rhythms of working-class life, and southern folk traditions. White patrons helped popularize the jazz, literature, and artworks of the Harlem Renaissance, but did they truly understand the Black American experience? Author and activist Jesse Fauset challenged white Americans to see the world through her eyes as she negotiated her daily life in New York City (See Some Notes on Color).

World War I and the 1920s set the course for the decades to come. The United States embraced a new role and direction in world affairs, and the government’s management of the war foreshadowed how it would combat the Great Depression and fight World War II. The nation both embraced and resisted cultural change on issues that still concern us. The modern civil rights movement was born, new rights for women were established, questions over civil liberties arose, and consumerism took hold as the driving engine of the economy. We live in the shadow of this era, and the documents in this collection make the connections between past and present readily apparent.

African Americans

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “Close Ranks,” July 1918

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “Returning Soldiers,” May 1919

- Charles R. Isum, A Black Soldier’s Experience in France, May 17, 1919

- Chicago Defender, Navigating the North, May 17, 1919

- Jessie Fauset, “Some Notes on Color,” March 1922

- Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” March 1925

Antiwar Dissent

- Alfred Bryan, “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” 1915

- George W. Norris, Opposition to War, April 4, 1917

- Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Espionage Act, June 15, 1917

- Socialist Party, “Wake Up America!” August 1917

- Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Sedition Act, May 16, 1918

Civil Liberties

- Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Espionage Act, June 15, 1917

- Doris Stevens, “Alice Paul in Prison,” 1917

- Socialist Party, “Wake Up America!” August 1917

- Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Sedition Act, May 16, 1918

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Schenck v. United States, March 3, 1919

- A. Mitchell Palmer, “The Case against the ‘Reds,’” February 1920

Cultural Conflict

- A. Mitchell Palmer, “The Case against the ‘Reds,’” February 1920

- William Jennings Bryan, Debating Darwinism: “God and Evolution,” February 26, 1922

- Harry Emerson Fosdick, Debating Darwinism: “Evolution and Mr. Bryan,” March 12, 1922

- Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” March 1925

- North American Review, Prohibition: Success or Failure? June–September 1925

- William Oscar Saunders, “Me and My Flapper Daughters,” August 1927

Economy

- Food Administration, “Food Will Win the War,” 1917

- Lucille Fee, Letters from a Working Wife, Fall 1918

- Literary Digest, “Henry Ford’s Five-Day Week,” April 29, 1922

- Woman’s Home Companion, “My Everyday Problems,” July 1923

- North American Review, Prohibition: Success or Failure? June–September 1925

- Sears, Roebuck and Co., Mail-Order Houses, 1927

- John J. Raskob, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” August 1929

Foreign Policy

- Woodrow Wilson, Declaration of Neutrality, August 19, 1914

- Woodrow Wilson, Responding to German Submarine Warfare, April 19, 1916

- Woodrow Wilson, “The World Must Be Made Safe for Democracy,” April 2, 1917

- Woodrow Wilson, The Fourteen Points, January 8, 1918

- Henry Cabot Lodge, Opposing the League of Nations, August 12, 1919

- Woodrow Wilson, Defending the Versailles Peace Treaty, September 25, 1919

- Frank B. Kellogg, Renouncing War: The Kellogg-Briand Pact, June 11, 1928

Path to War, 1914–1917

- Woodrow Wilson, Declaration of Neutrality, August 19, 1914

- Fred Spear, “Enlist,” 1915

- Woodrow Wilson, Responding to German Submarine Warfare, April 19, 1916

- Arthur, Zimmermann, The Zimmermann Telegram, January 16, 1917

- Woodrow Wilson, “The World Must Be Made Safe for Democracy,” April 2, 1917

- George W. Norris, Opposition to War, April 4, 1917

Peace

- Woodrow Wilson, The Fourteen Points, January 8, 1918

- Henry Cabot Lodge, Opposing the League of Nations, August 12, 1919

- Woodrow Wilson, Defending the Versailles Peace Treaty, September 25, 1919

- Warren G. Harding, Laying to Rest an Unknown American Soldier, November 11, 1921

- Frank B. Kellogg, Renouncing War: The Kellogg-Briand Pact, June 11, 1928

Propaganda

- Fred Spear, “Enlist,” 1915

- James Montgomery Flagg, Recruitment Poster, 1917

- Socialist Party, “Wake Up America!” August 1917

- Food Administration, “Food Will Win the War,” 1917

Soldiers

- Sergeant A. Judson Hanna and Lieutenant Colonel Ashby Williams, Fighting in World War I, September 1918

- Charles R. Isum, A Black Soldier’s Experience in France, May 17, 1919

- Warren G. Harding, Laying to Rest an Unknown American Soldier, November 11, 1921

Women

- Doris Stevens, “Alice Paul in Prison,” 1917

- Carrie Chapman Catt, Open Address to the U.S. Congress, November 1917

- Food Administration, “Food Will Win the War,” 1917

- Lucille Fee, Letters from a Working Wife, Fall 1918

- Jessie Fauset, “Some Notes on Color,” March 1922

- Woman’s Home Companion, “My Everyday Problems,” July 1923

- William Oscar Saunders, “Me and My Flapper Daughters,” August 1927

For each of the documents in this collection, we suggest below questions relevant for that document alone and questions that require comparison between documents.

Woodrow Wilson, Declaration of Neutrality, August 19, 1914

- Why did Wilson focus more on domestic tranquility than the international situation? What did his concerns reveal about the impact of large-scale immigration?

- Wilson claimed that “the effect of the war upon the United States will depend upon what American citizens say and do.” According to Senator George W. Norris, did Americans heed Wilson’s request and remain neutral from 1914 to 1917?

Alfred Bryan, “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” 1915

- How did the song serve as propaganda for the peace movement? What civic role did it envision for mothers? Why didn’t the song mention a father’s grief?

- How does the song’s antiwar argument compare to the Socialist Party’s objections to entering the war?

- What emotions does the poster evoke? The German government pointed out that the Lusitania was carrying munitions and Americans had been warned to stay out of the war zone. Do these facts change the meaning of the poster?

- How did the “Enlist” poster and antiwar song “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” use women and children as symbols to make larger arguments about the European war? What does this symbolism suggest about gender roles in American society?

Woodrow Wilson, Responding to German Submarine Warfare, April 19, 1916

- How did Wilson define and defend “freedom of the seas” in this address? What image did he paint of Germany? Critics faulted him for making no mention of the British naval blockade of the North Sea that hampered German trade. Did they have a point?

- How had Wilson’s concept of neutrality changed since he issued his declaration of neutrality in 1914?

Arthur Zimmermann, The Zimmermann Telegram, January 16, 1917

- Why did Zimmermann expect his proposals to interest Mexico and Japan? Did the Zimmermann Telegram represent a credible threat to the United States?

- How did Woodrow Wilson address the Zimmermann Telegram in his war address (See The World Must Be Made Safe for Democracy)? Was the telegram a major reason he decided to ask for a declaration of war against Germany?

Woodrow Wilson, “The World Must Be Made Safe for Democracy,” April 2, 1917

- Did Wilson have a strong case for declaring war against Germany? What war aims did he outline in his address besides defeating Germany?

- How did Russia factor into Wilson’s thinking in his war address and the Fourteen Points?

George W. Norris, Opposition to War, April 4, 1917

- What link did Norris make between foreign policy and economics? What critique was he offering of the economic class structure in the United States?

- How did Norris challenge Woodrow Wilson’s rationale for going to war? Who had the better argument, Norris or Wilson?

Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Espionage Act, June 15, 1917.

- What does the provision banning certain materials from the mails reveal about how information circulated during World War I? How might newspapers and magazines react to keep their mailing privileges?

- How did the Supreme Court apply these sections of the Espionage Act to uphold the conviction of Charles T. Schenck in Schenck vs. United States?

James Montgomery Flagg, Recruitment Poster, 1917

- The government used this recruitment poster in both world wars. What makes it an effective piece of propaganda? In what ways is it ineffective?

- How does the composition of Flagg’s poster compare to that of Spear’s “Enlist” poster?

Doris Stevens, “Alice Paul in Prison,” 1917

- How did Stevens frame Alice Paul’s story of imprisonment? What image of the National Woman’s Party did she present to the public?

- How did Lucille Fee’s encounter with male authority compare to Alice Paul’s? What do these encounters reveal about gender roles in the early twentieth century?

Socialist Party, “Wake Up America!” August 1917

- What were the Socialist Party’s key objections to conscription and the war? How is the political ideology of the Socialist Party apparent throughout the circular?

- Did Senator George W. Norris make similar or different arguments against the war?

Carrie Chapman Catt, Open Address to the U.S. Congress, November 1917

- How did Catt counter the arguments made by opponents of female suffrage?

- How did the tactics of the National American Woman Suffrage Association compare to those employed by the National Woman’s Party?

Food Administration, “Food Will Win the War,” 1917

- How did the Food Administration try to gain public compliance with food conservation measures? Are there any potential negative consequences to the approaches taken?

- How did Food Administration propaganda and James Montgomery Flagg’s recruitment poster define a citizen’s patriotic obligation in wartime? What reciprocal responsibilities does the government have to the citizenry?

Woodrow Wilson, The Fourteen Points, January 8, 1918

- Was Wilson’s peace proposal idealistic, pragmatic, or a combination of both?

- Are Wilson’s Fourteen Points consistent with the goals he outlined in his war address?

Sixty-fifth U.S. Congress, Sedition Act, May 16, 1918

- Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines sedition as “incitement of resistance to or insurrection against lawful authority.” How did the Sedition Act define sedition? Are the two definitions compatible?

- Would Senator George W. Norris’s 1917 speech have violated the law if he had given it after the passage of the Sedition Act?

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Close Ranks,” July 1918

- Was Du Bois offering sound advice? What objections might members of the African American community raise?

- How does Du Bois’s “Close Ranks” editorial compare to the Chicago Defender’s advice to Black southern migrants?

Lucille Fee, Letters from a Working Wife, Fall 1918

- How was Lucille’s work both frustrating and satisfying?

- Were Lucille Fee’s challenges as a working wife in wartime America different from the everyday problems faced by female homemakers in 1920s (See My Everyday Problems)?

- What was it like to endure an artillery bombardment, according to Hanna and Williams? Why did they share these experiences with the public?

- Are their accounts similar or different to the description of combat given by President Warren G. Harding at the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in 1921?

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Schenck v. United States, March 3, 1919

- What did Holmes mean when he used the phrase “clear and present danger” to set a constitutional limit on free speech? Are there any flaws in his reasoning?

- Holmes discussed the Socialist Party pamphlet in detail. Did he correctly summarize its main points and likely influence on potential recruits?

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Returning Soldiers,” May 1919

- What was Du Bois’s message to returning soldiers? Why did he see the war as a turning point for the civil rights movement?

- How does the tone and purpose of “Returning Soldiers” differ from “Close Ranks”? What accounts for the differences?

Charles R. Isum, A Black Soldier’s Experience in France, May 17, 1919

- How did Isum’s experiences in France change his worldview? How did he manage to fight back against racial prejudice and discrimination while still in uniform?

- Why did reading “Returning Soldiers” inspire Isum to write to Du Bois? How do his experiences fit into the narrative that Du Bois presented in his editorial? Are there any differences?

Chicago Defender, Navigating the North, May 17, 1919

- Why did the Chicago Defender publish this list of behaviors to avoid? What does it reveal about the state of race relations in Chicago? About tensions between longtime Black residents and newcomers?

- The Chicago Defender published this list the same month that W. E. B. Du Bois wrote “Returning Soldiers”. How might returning Black veterans respond to the newspaper’s suggestions?

Henry Cabot Lodge, Opposing the League of Nations, August 12, 1919

- What were Lodge’s main objections to joining the League of Nations? What role did he prefer for the United States in global affairs?

- How does this speech compare to Woodrow Wilson’s 1914 declaration of neutrality?

Woodrow Wilson, Defending the Versailles Peace Treaty, September 25, 1919

- Why did Wilson think the United States should join the League of Nations? How would joining the League of Nations potentially change the role that the United States plays in global affairs?

- Who makes the more compelling argument on whether the United States should join the League of Nations; Senator Henry Cabot Lodge or Wilson?

A. Mitchell Palmer, “The Case against the ‘Reds,’” February 1920

- What evidence did Palmer offer to support his claim that communism posed a serious domestic threat? What actions did the Justice Department take under his leadership to address this perceived threat?

- How did the Espionage and Sedition Acts lay the groundwork for the First Red Scare?

Warren G. Harding, Laying to Rest an Unknown American Soldier, November 11, 1921

- Why did Harding emphasize heroism, patriotism, and sacrifice in characterizing the life and death of the Unknown Soldier?

- Consider how Harding and Woodrow Wilson portrayed fallen American soldiers in their speeches. What sentiments were they trying to arouse among their listeners? To what end?

William Jennings Bryan, Debating Darwinism: “God and Evolution,” February 26, 1922

- What were Bryan’s main objections to teaching the theory of evolution in schools? What rhetoric did he employ to build his case?

- Compare how Bryan and William Oscar Saunders characterized the younger generation. What do their attitudes and concerns reveal about cultural and generational conflict in the 1920s?

Harry Emerson Fosdick, Debating Darwinism: “Evolution and Mr. Bryan,” March 12, 1922

- How could one believe in both evolution and God, according to Fosdick?

- Fosdick and William Jennings Bryan offered competing interpretations of the compatibility of religion and evolution. Who makes the stronger case?

Jessie Fauset, “Some Notes on Color,” March 1922

- What challenges did Fauset face as a Black woman living in the North? How did anti-Black racial prejudice affect her well-being and daily life?

- Compare the strategies that Fauset employed with the tips suggested by the Chicago Defender to navigate life in the North. What are the similarities and differences?

Literary Digest, “Henry Ford’s Five-Day Week,” April 29, 1922

- Ford’s five-day workweek plan received mixed reviews. What did his supporters champion about the plan? What did his critics say against it?

- How were working-class men depicted in this commentary and in the debate over Prohibition?

Woman’s Home Companion, “My Everyday Problems,” July 1923

- What common threads run through these letters? What insights do they offer into gender roles in the 1920s?

- How might William Oscar Saunders’s “flapper” daughters view the lives of the married women writing these letters?

Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” March 1925

- How did Locke define the “New Negro”? What was the relationship between artistic expression and activism during the Harlem Renaissance?

- How well do W. E. B. Du Bois, Charles R. Isum, and Jessie Fauset fit Locke’s definition of the “New Negro”?

North American Review, Prohibition: Success or Failure? June–September 1925

- What were the key arguments made by supporters of Prohibition? What key arguments did its opponents make? Who has the stronger argument?

- What do disagreements over Prohibition and the teaching of evolution in schools (See Debating Darwinism: God and Evolution and Debating Darwinism: Evolution and Mr. Bryan) reveal about cultural conflict in the 1920s?

Sears, Roebuck and Co., Mail-Order Houses, 1927

- How did the catalog portray homeownership? What do the blueprints suggest about varying standards of living in the 1920s?

- What do the Sears Modern Home catalog and commentary on Henry Ford’s five-day workweek proposal reveal about the economic climate in the 1920s?

William Oscar Saunders, “Me and My Flapper Daughters,” August 1927

- How did Saunders account for the rebellious spirit of his daughters and the general lack of understanding between the younger and older generations? How did he propose to heal this generational divide?

- Which elements of conventional gender roles did female suffrage activists (See Alice Paul in Prison and Open Address to the U.S. Congress) and “flappers” challenge? Which elements did they embrace?

Frank B. Kellogg, Renouncing War: The Kellogg-Briand Pact, June 11, 1928

- Why did Kellogg repeatedly emphasize favorable public opinion in his address? How did he defend the nonaggression pact against its critics?

- How did the shadow of World War I shape the foreign policy initiatives of Warren G. Harding and Kellogg? Did their initiatives incorporate or reject Wilsonian ideals (See The Fourteen Points)?

John J. Raskob, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” August 1929

- What distinction did Raskob make between saving and constructive saving; debt and beneficial borrowing? What did he mean when he said that “everybody ought to be rich”?

- Both Raskob and the Sears Modern Homes catalog promoted installment purchasing plans. What potential value did these plans have for the consumer, creditors, and the economy at large? Were there any potential drawbacks to installment plans?

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Cooper, John Milton Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 2009.

Dumenil, Lynn. The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Fass, Paula S. The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920’s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Keene, Jennifer D. The United States and the First World War. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2022.

Larson, Edward J. Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion. Rev. ed. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

Lentz-Smith, Adriane. Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. New York: Penguin Books, 1997.

Neiberg, Michael S. The Treaty of Versailles: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Prohibition’s Greatest Myths: The Distilled Truth about America’s Anti-Alcohol Crusade, ed. Michael Lewis and Richard F. Hamm. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

Watts, Steven. The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century. New York: Knopf, 2005.