Introduction

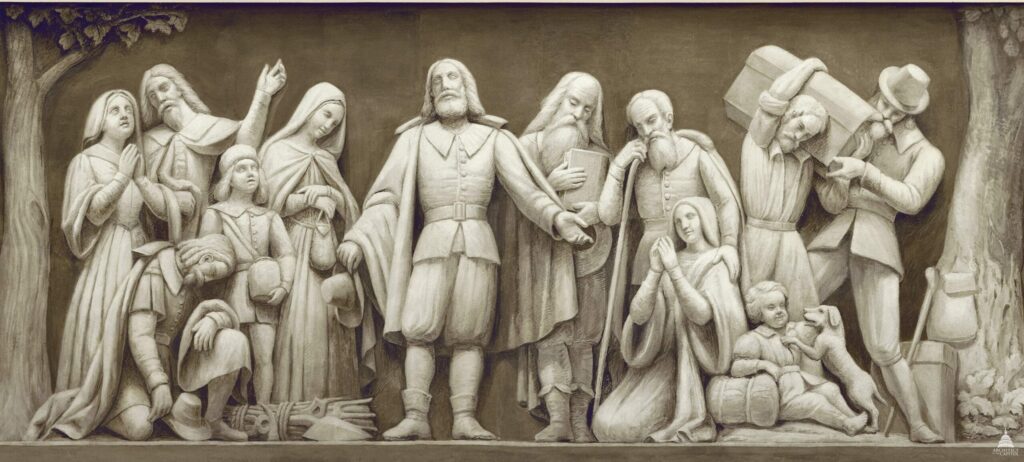

Many (although not all) of the early colonists in New England were religious dissenters – persons who had separated from established churches in Great Britain – for whom the New World represented a haven from royal persecution. Particularly in the colonies of Plymouth and Massachusetts, shared religious commitments and the experience of persecution led community leaders to frame their colonies as quasi-utopian places for the faithful to prosper. Given the opportunity to create societies according to their own understandings, they did not hesitate to engage in radical social experiments meant to prove that “godliness” was not only a spiritual virtue but had practical implications for everyday life as well. From the beginning, ministers like Robert Cushman and civil magistrates like William Bradford and John Winthrop urged their citizens to recognize that they were drawn together for a purpose far beyond their own liberty, or even security, and to place the welfare of the community as a whole above their own.

Cushman and Winthrop, for example, offered advice to the colonists about how to best prepare themselves mentally and spiritually for the arduous task of a godly commonwealth. Both men urged their audiences to embrace the Christian ideal of “brotherly affection.” In response to the extraordinary demands of colonization, they urged their listeners to willingly be generous and abjure “self-love.” This was taken quite literally at Plymouth, where the London-based investors funding the colony required the colonists to agree that everything would be held in common for the first seven years, and then at the end of that term, all property/profits divided equally between colonists and investors. Although this experiment with communalism failed rather spectacularly and was abandoned after only three years, the ethic of neighborliness continued to be an important touchstone in both colonies throughout the seventeenth century.

New colonists continued to arrive regularly throughout the 1630s and 1640s, and as the population increased, the colonists struggled to balance their desire to remain true to their founders’ idealized notion of community with the realities of life and commerce. In Massachusetts Bay, for example, merchants such as Robert Keayne were expected to moderate their desire for profit with a due consideration of the extreme needs and limited means of their customers. Keayne, who was both a shrewd businessman and a devout member of his church, apparently struggled his whole life to meet this standard; at various times, he was admonished by both his congregation and the civil government for unjust business practices (see Admonishment and Reconciliation of Robert Keayne with the Church, 1639 – 1640). This accusation apparently stung so deeply, Keayne used his last will and testament to present an extensive Apologia for his actions.

Robert Cushman, The Sin and Danger of Self-Love . . . 1621 (Boston: 1846).

Let no man seek his own; but every man another’s wealth – 1 Cor. x. 24.

. . .

The meaning then summarily is, as if he had said, the bane of all these mischiefs which arise among you is, that men are too cleaving to themselves and their own matters, and disregard and condemn all others; and therefore I charge you, let this self-seeking be left off, and turn the stream another way, namely, seek the good of your brethren, please them, honor them, reverence them, for otherwise it will never go well among you.

Objection. But does not the Apostle elsewhere say? That he, that cares not for his own, is worse than an infidel.

Answer. True, but by “own” there, he means properly, a man’s kindred, and here by “own” he means properly a man’s self.

Secondly, he there especially taxes such as were negligent in their labors and callings, and so made themselves unable to give relief and entertainment to such poor widows and orphans as were of their own flesh and blood. . . .

Doctrine 1. All men are too apt and ready to seek themselves too much, and to prefer their own matters and causes beyond the due and lawful measure, even to excess and offense against God, yea danger of their own souls. . . .

Objection. It is a point of good natural policy, for a man to care and provide for himself.

Answer. . . . I say he must seek . . . the comfort, profit and benefit of his neighbor, brother, associate, etc. His own good he need not seek, it will offer itself to him every hour; but the good of others must be sought. . . .

As a man may neglect, in some sort the general world, yet those to whom he is bound, either in natural, civil, or religious bands, them he must seek how to do them good. . . . Now for one member in the body to seek himself, and neglect all others, were as if a man should clothe one arm or one leg of his body with gold and purple, and let all the rest of the members go naked.

Now brethren, I pray you, remember yourselves, and know, that you . . . have given your names and promises one to another, and covenanted here to cleave together in the service of God, and the king; what then must you do? May you live as retired hermits? And look after no body? Nay, you must seek still the wealth of one another. . . . [My neighbor] is as good a man as I, and we are bound each to other, so that his wants must be my wants, his sorrows my sorrows, his sickness my sickness, and his welfare my welfare, for I am as he is. And such a sweet sympathy were excellent, comfortable, yea, heavenly, and is the only maker and conservator of churches and commonwealths, and where this is wanting, ruin comes on quickly, as it did here in Corinth. . . .

It wonderfully encourages men in their duties, when they see the burden equally borne; but when some withdraw themselves and retire to their own particular ease, pleasure, or profit, what heart can men have to go on in their business? . . . Will not a few idle drones spoil the whole stock of laborious bees; so one idle-belly, one murmurer, one complainer, one self-lover will weaken and dishearten a whole colony. . . .

The present necessity requires it, as it did in the days of the Jews, returning from captivity, and as it was here in Corinth. The country is yet raw, the land untilled, the cities not builded, the cattle not settled; we are compassed about with a helpless and idle people, the natives of this country, which cannot in any comely or comfortable manner help themselves, much less us.

. . . [I]f your difficulties be great, you had need to cleave the faster together, and comfort and cheer up one another, laboring to make each other’s burdens lighter; there is no grief so tedious as a churlish companion, and nothing makes sorrows easy more than cheerful associates. Bear you therefore one another’s burden, and be not a burden one to another; avoid all factions, forwardness, singularity and withdrawings, and cleave fast to the Lord, and one to another continually. . . .