Introduction

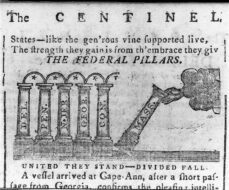

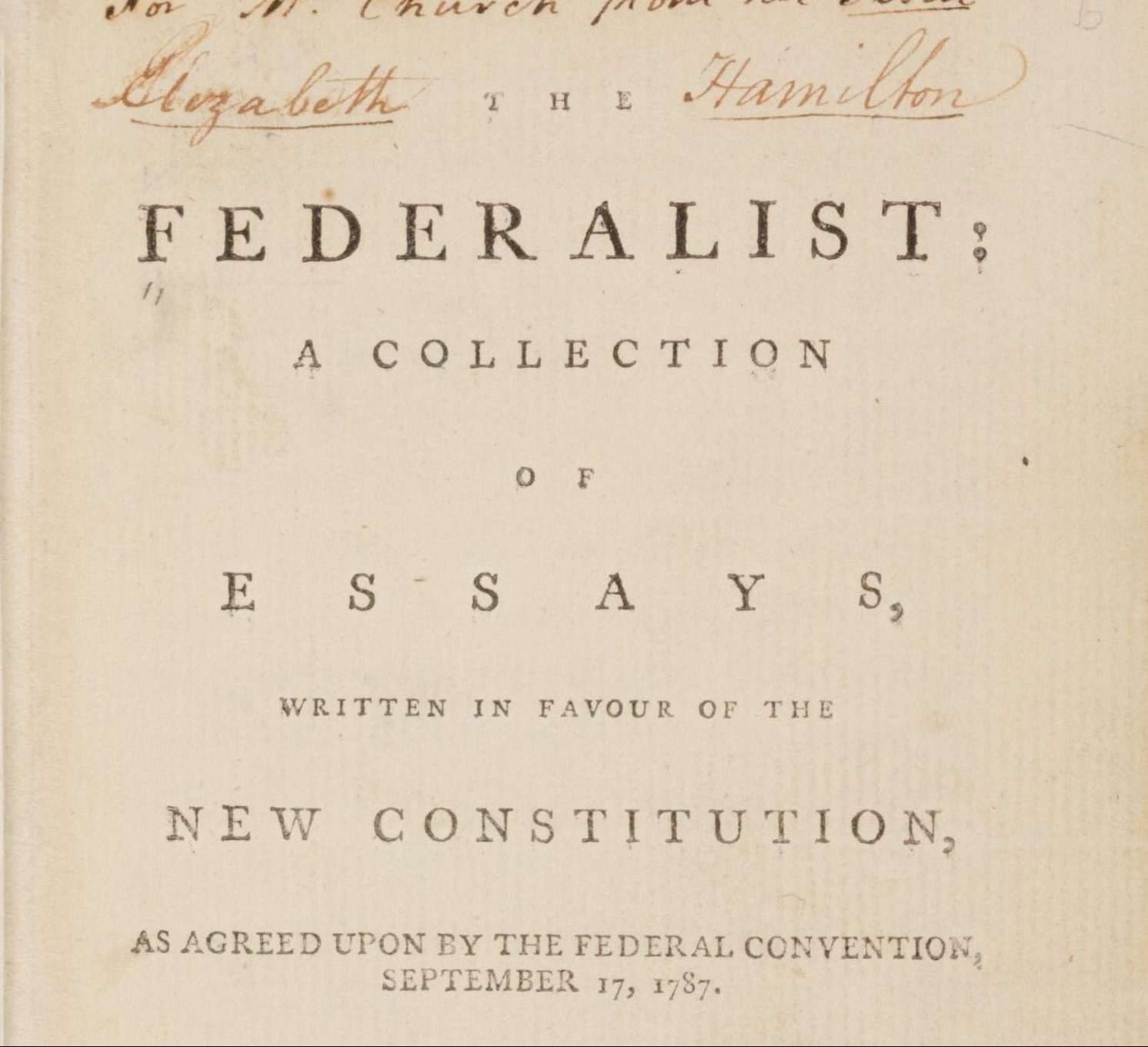

This letter is part of our Four-Act Drama, a Constitutional Convention role-playing scheme for educators. For more information on our comprehensive exhibit on the Constitutional Convention, click here.

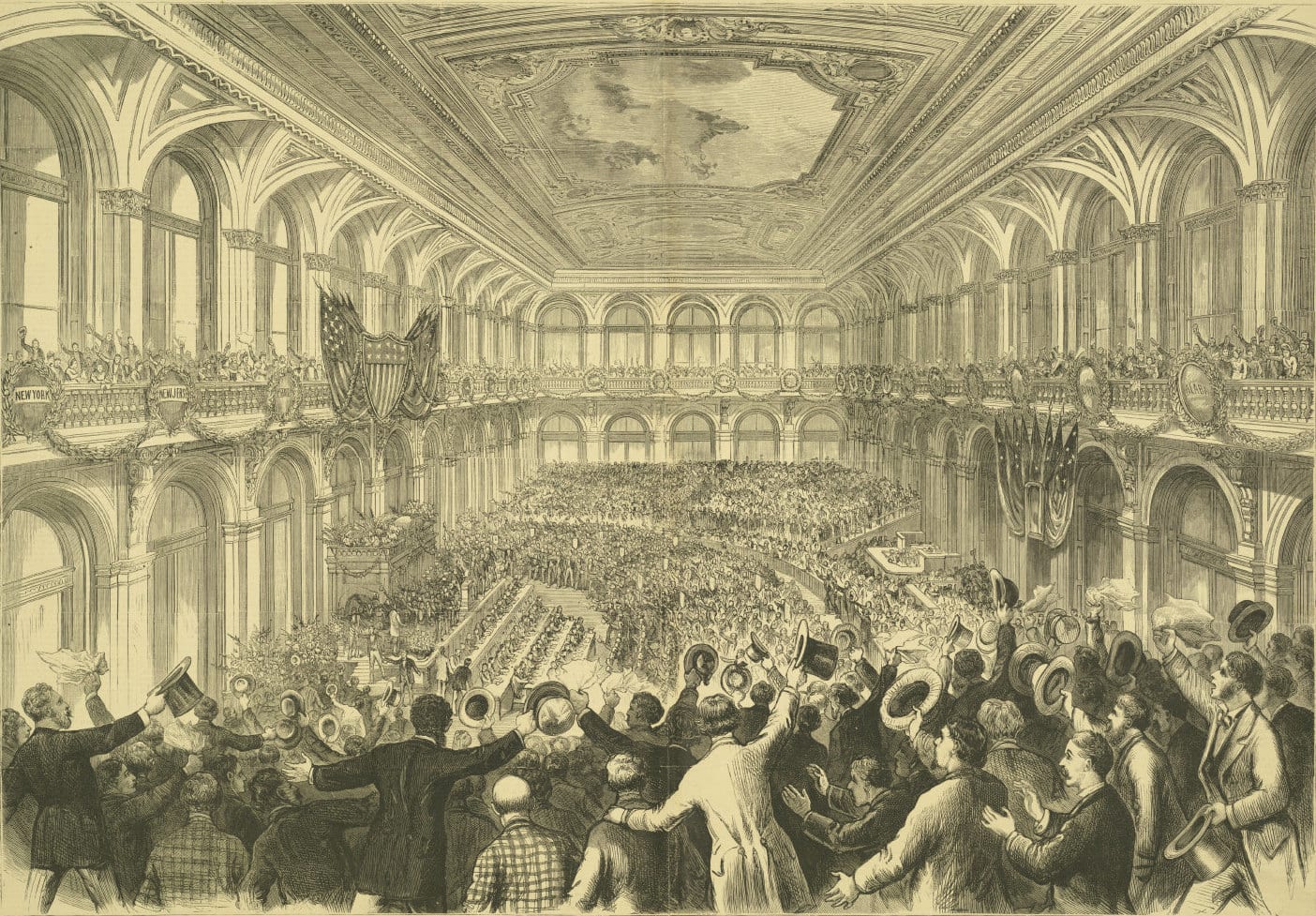

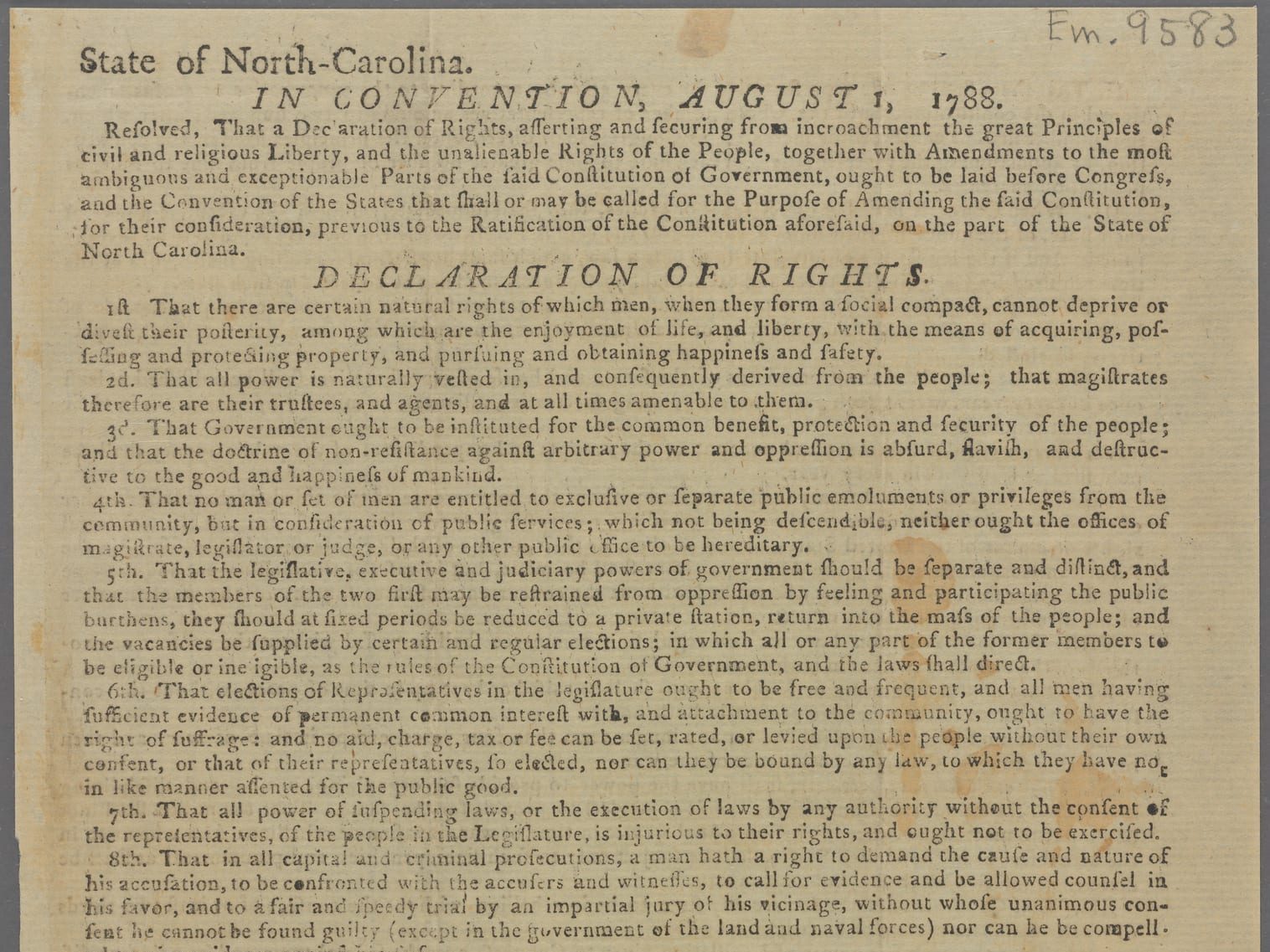

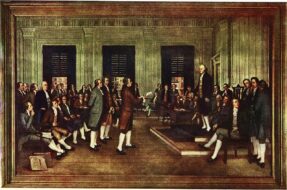

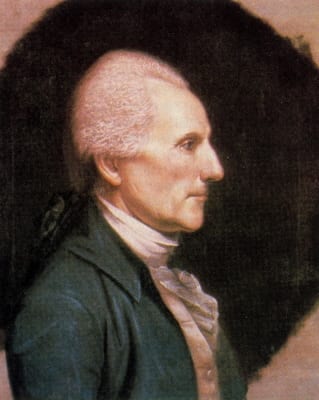

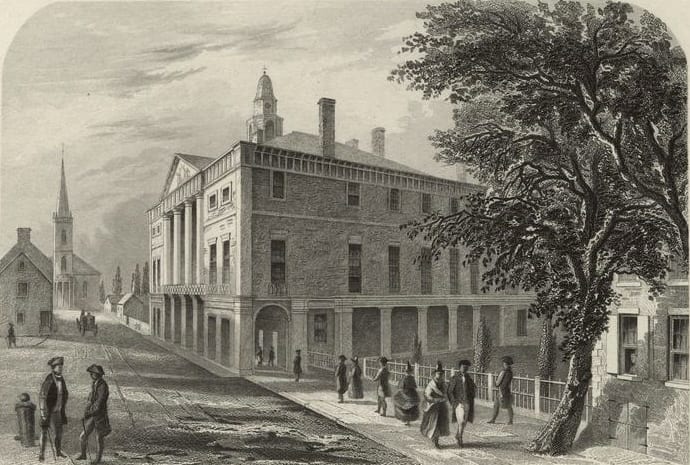

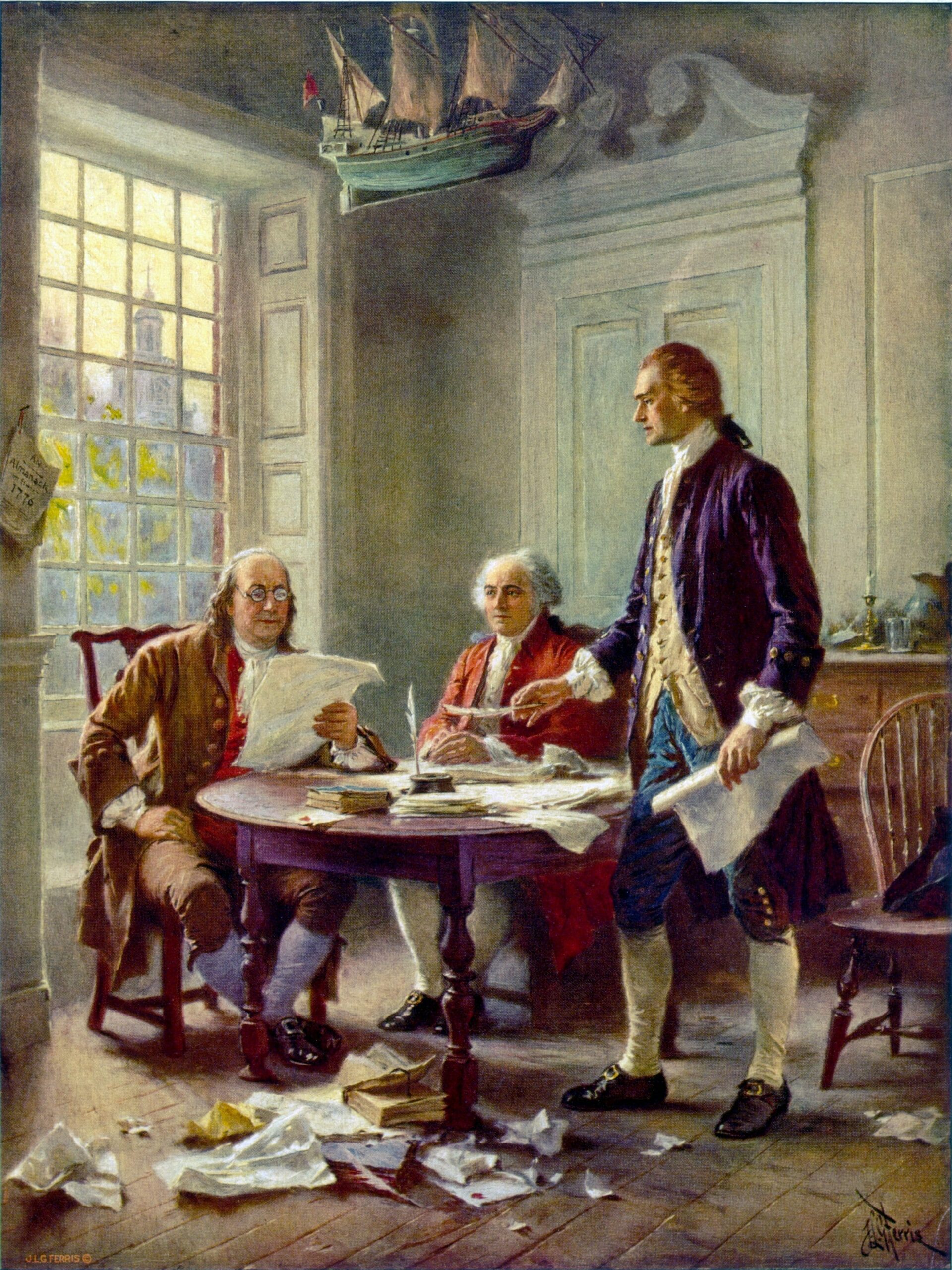

In late July, the Convention adjourned for two weeks, allowing the Committee of Detail to organize and refine the various proposals debated during June and July. Delegates reconvened on August 6 to review the Committee’s report, which consisted of 23 articles outlining the details of the proposed government.

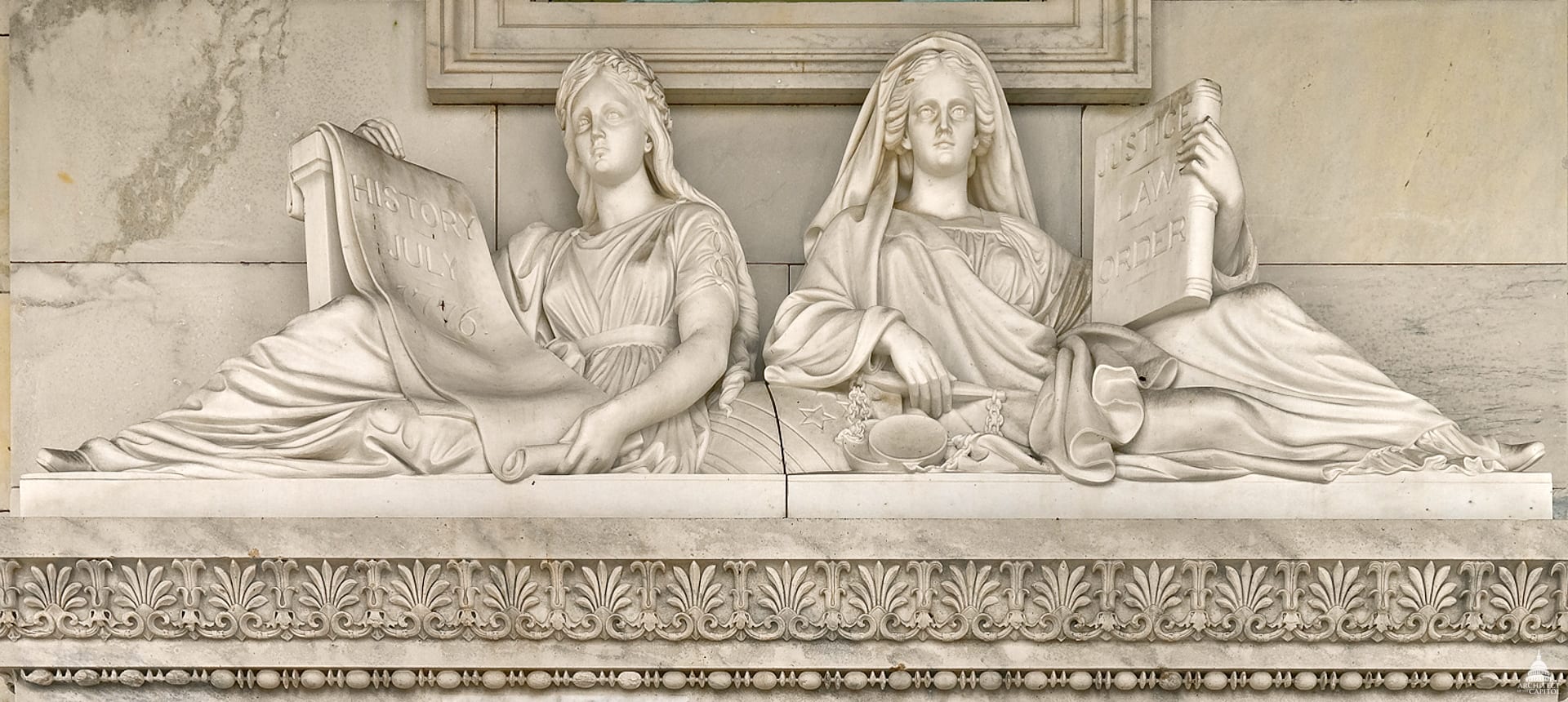

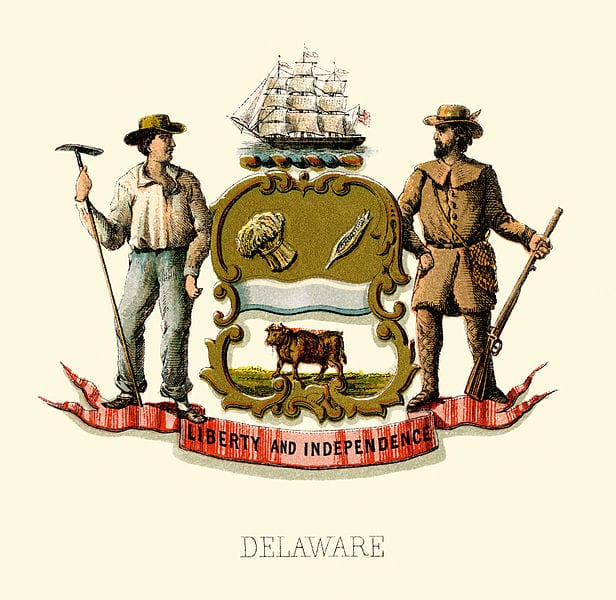

The discussions in June and July allowed delegates to develop a new structure for the government, marking a departure from its organization under the Articles of Confederation. With the creation of a bicameral legislature, delegates focused on defining Congress’ powers and its relationship to state governments. While there was consensus on granting greater authority to the central government, delegates disagreed on the extent of congressional power and its impact on the sovereignty of state governments. The expansion from a single branch of government to three also prompted complex discussions about the separation of powers within the central government.

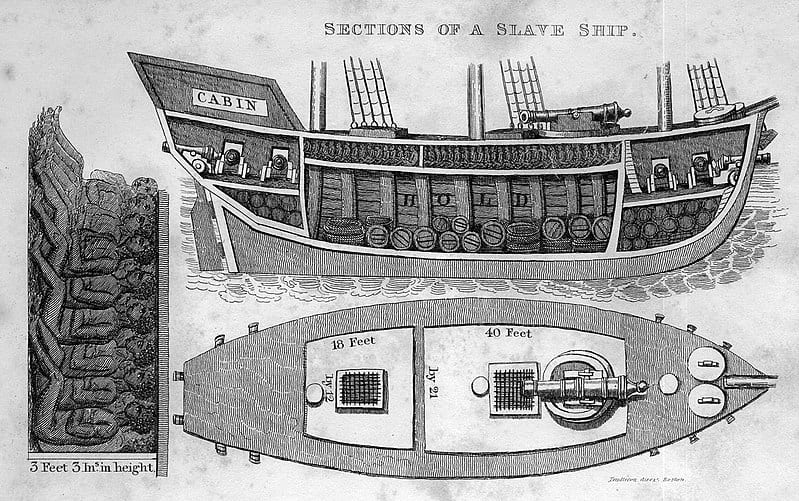

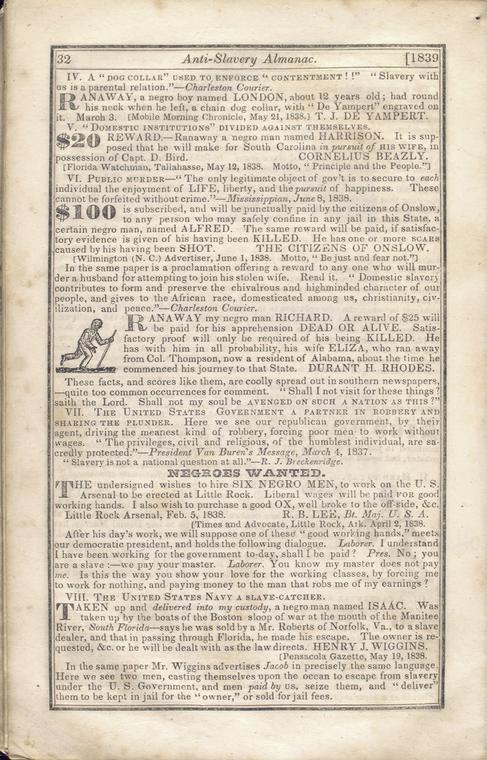

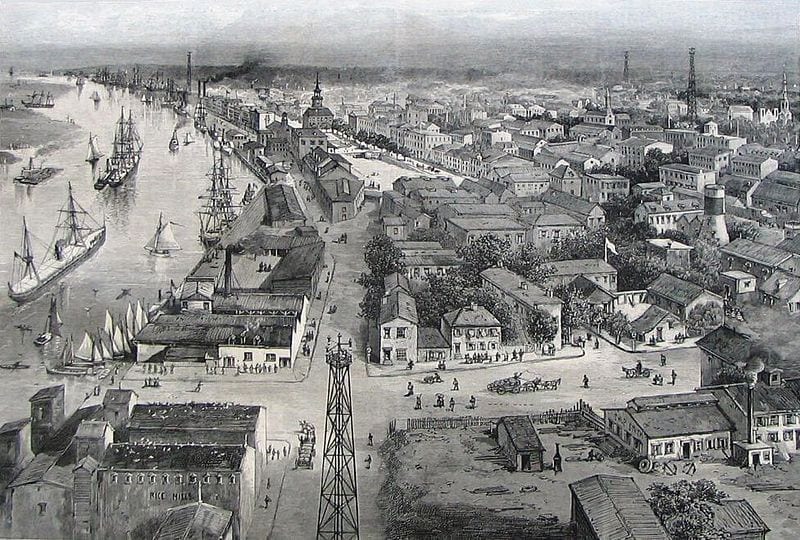

Throughout the continued deliberations, slavery emerged as a divisive topic, particularly concerning Congress’ authority to regulate or abolish it. The Committee report prohibited Congress from regulating the slave trade or discouraging it through taxation, though this language would differ in the final draft of the Constitution (see Article I, Section 9, Clause 1). While correspondence after the two-week break does not specifically mention the slavery debate, Madison’s notes indicate that it was a central topic during the third week of August. For further information regarding slavery’s treatment at the Convention, see debates on representation, the slave trade, and the fugitive slave clause.

As these broader discussions unfolded, delegate correspondence revealed continued frustrations with the prolonged Convention timeline. Many had initially anticipated a brief meeting to revise the Articles of Confederation, but as the Convention stretched into its third month with no clear end in sight, some delegates grew increasingly frustrated with the slow pace of progress. Adding to these frustrations were tensions among delegates, driven largely by conflicts between large and small states and differing regional interests.

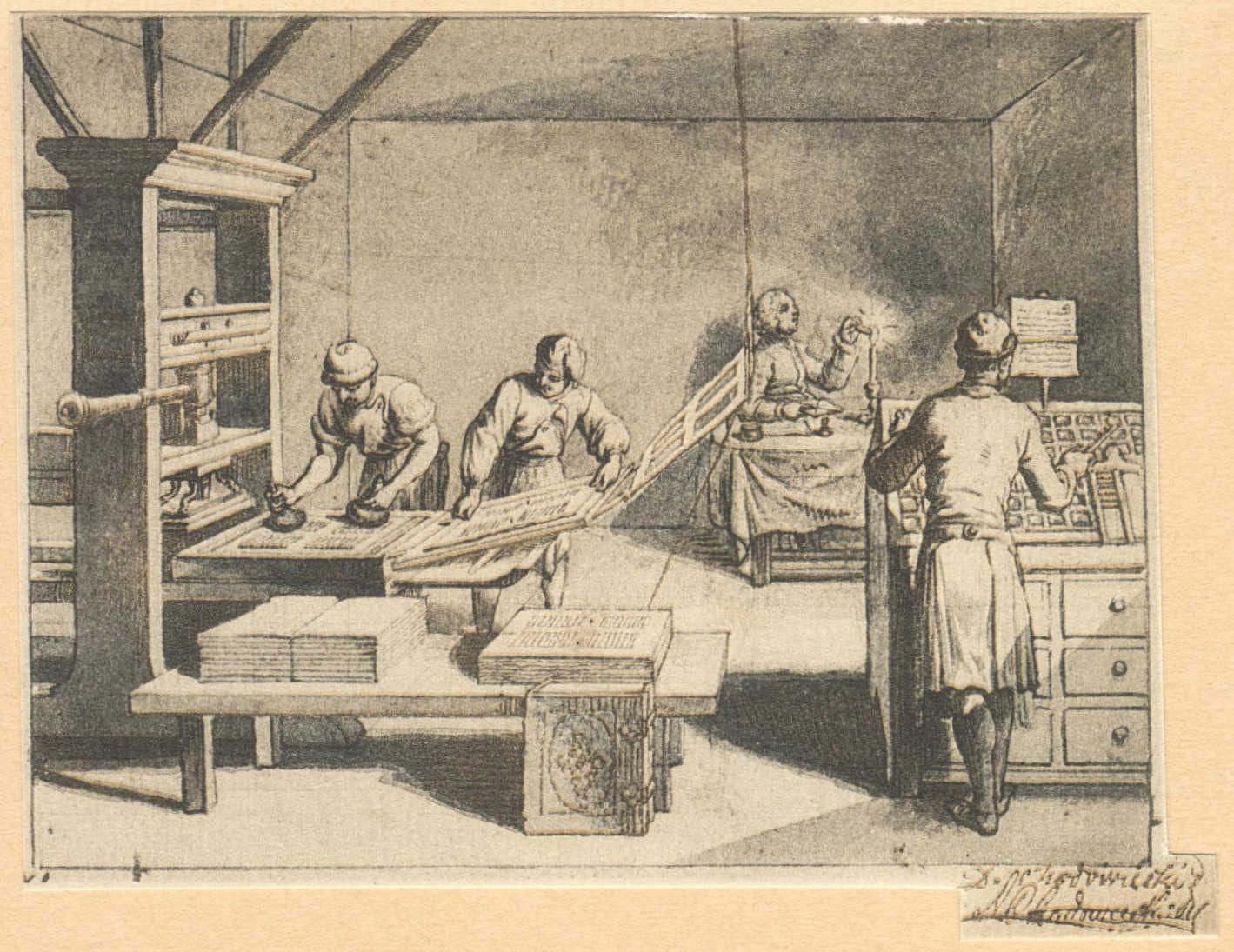

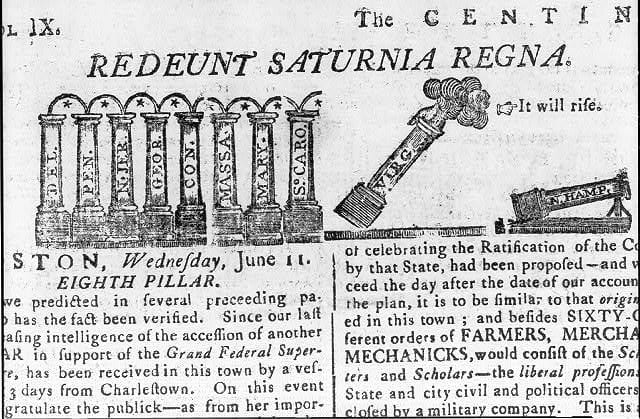

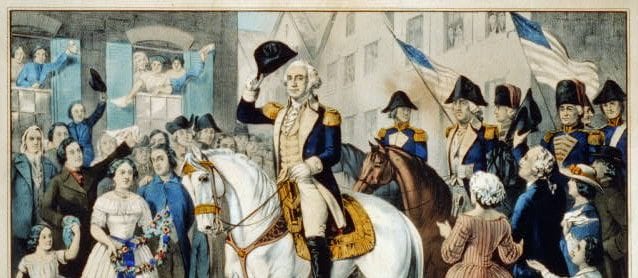

Uncertainty also emerged regarding public reception of the proposed government. Because of the secrecy rule, outside public opinions regarding the Convention’s work varied. While some delegates expressed concerns about the public’s willingness to approve a framework so vastly different than the Articles of Confederation, others, like Washington, remained optimistic. Washington believed the proposed Constitution was “the best that can be obtained at the present moment under such diversity of ideas as prevail.”

By August 31, delegates concluded their review of the Committee of Detail Report. As the Convention entered its fourth month, setting the scene for the final act of the Four Act Drama, the focus shifted toward the executive branch. Delegates ventured into uncharted territory as they contended with the scope of executive power, ultimately shaping the final framework of the Constitution.

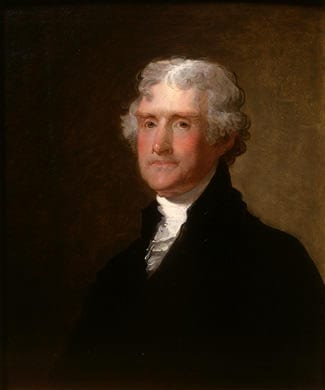

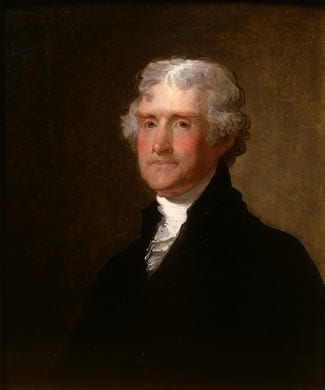

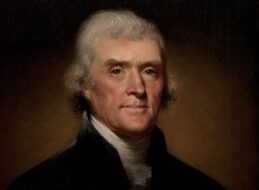

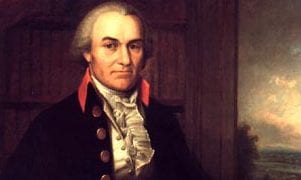

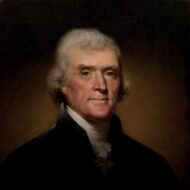

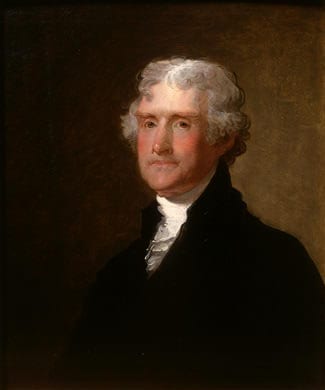

“From Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 30 August 1787,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0075.

From the separation of the Notables1 to the present moment has been perhaps the most interesting interval ever known to this country2. The propositions of the Government, approved by the Notables, were precious to the nation and have been in an honest course of execution, some of them being carried into effect, and others preparing. Above all the establishment of the Provincial assemblies, some of which have begun their sessions, bid fair to be the instrument for circumscribing the power of the crown and raising the people into consideration. The election given to them is what will do this. Tho’ the minister who proposed these improvements seems to have meant them as the price of the new supplies, the game has been so played as to secure the improvements to the nation without securing the price. The Notable spoke softly on the subject of the additional supplies, but the parliament took them up roundly, refused to register the edicts for the new taxes, till compelled in a bed of justice and preferred themselves to be transferred to Troyes rather than withdraw their opposition. It is urged principally against the king, that his revenue is 130. millions more than that of his predecessor was, and yet he demands 120. millions further. . . . In the mean time all tongues in Paris . . . have been let loose, and never was a license of speaking against the government exercised in London more freely or more universally. Caricatures, placards, bon mots3, have been indulged in by all ranks of people, and I know of no well attested instance of a single punishment. For some time mobs of 10; 20; 30,000 people collected daily, surrounded the parliament house, huzzaed the members, even entered the doors and examined into their conduct, took the horses out of the carriages of those who did will, and drew them home. The government thought it prudent to prevent these, drew some regiments into the neighborhood, multiplied the guards, had the streets constantly patrolled by strong parties, suspended privileged places, forbad all clubs, &ct. The mobs have ceased: perhaps this may be partly owing to the absence of parliament. . . . I have brought together the principal facts from the adjournment of the Notables to the present moment which, as you will perceive form their nature, required a confidential conveyance. I have done it the rather because, tho’ you will have heard many of them and seen them in the public papers, yet floating in the mass of lies which constitute the atmospheres of London and Paris, you may not have been sure of their truth: and I have mentioned every truth of any consequence to enable you to stamp as false the facts pretermitted. I think that in the course of three months the royal authority has lost, and the rights of the nation gained, as much ground, by a revolution of public opinion only, as England gained in all her civil wars under the Stuarts4. I rather believe too they will retain the ground gained, because it is defended by the young and the middle aged, in opposition to the old only. The first party increases, and the latter diminishes daily from the course of nature. . . .

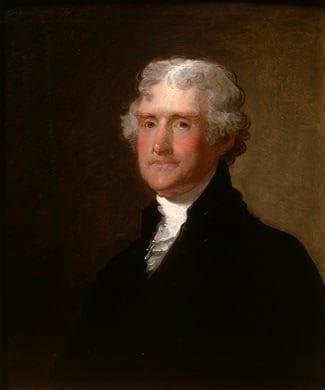

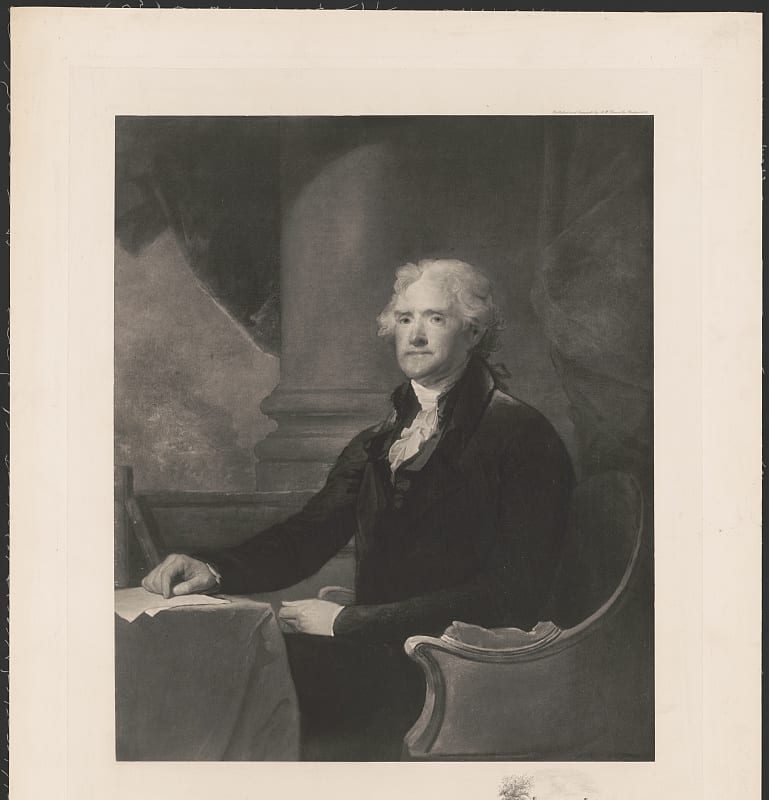

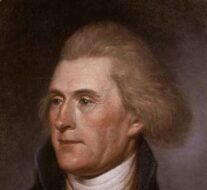

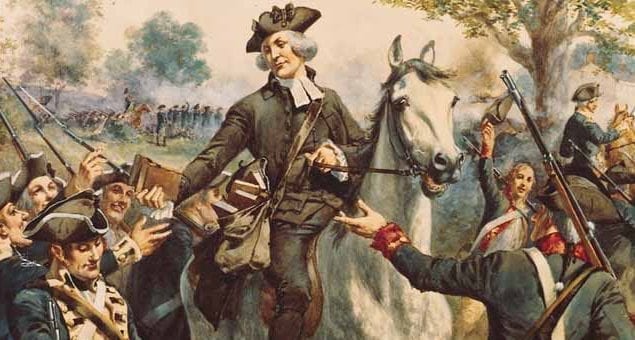

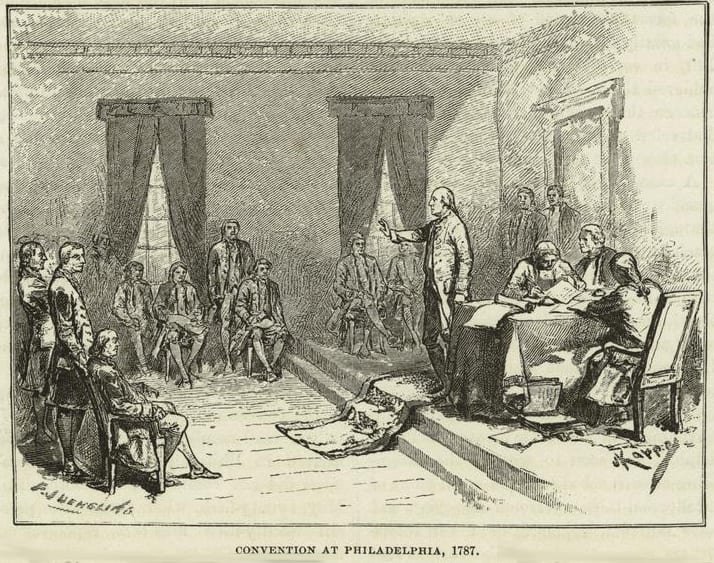

I have news from America as late as July 19. Nothing had then transpired from the Federal convention. I am sorry they began their deliberations by so abominable a precedent as that of tying up the tongues of their members. Nothing can justify this example but the innocence of their intentions, and ignorance of the value of public discussions. I have no doubt that all their other measures will be good and wise. it is really an assembly of demigods. Genl. Washington5 was of opinion they should not separate till October. I have the honour to be with every sentiment of friendship and respect Dear Sir.

Your most obedient and most humble servant,

TH:

- 1. A group of influential individuals belonging to the Assembly of Notables, brought together by King Louis XVI. Tasked with helping resolve some of the country’s financial issues, many members of the assembly disagreed with the King’s plans. These tensions would play a role in the lead up to the French Revolution.

- 2. Referencing Jefferson’s role as Minister to France from 1784–1789.

- 3. A witty or clever remark.

- 4. The Stuart dynasty ruled the United Kingdom from 1603–1714. Their reign was marked by significant religious and political unrest, including a civil war.

- 5. George Washington (1732–1799), delegate from Virginia who also presided as president at the Convention

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)