Introduction

Virginia v. Black considered two different acts of cross burning. The first instance involved Imperial Grand Wizard Barry Black’s burning of a cross on private property during a Klan membership rally. The second instance involved two teenagers, Richard Elliott and Jonathan O’Mara, who drove a truck onto their African American neighbor’s lawn, planted a cross, and burned it.

At issue in Virginia v. Black was a Virginia state law that banned cross burning with “an intent to intimidate a person or group of persons.” The same Virginia statute included a provision specifying that “any such burning . . . shall be prima facie evidence of an intent to intimidate a person or group.” Prima facie is a Latin phrase loosely translated in English to mean “at first sight.” In legal terms, it refers to the instructions given to a jury that their first impression of the facts is correct, until proven otherwise. Thus, under this provision, jurors were correct to infer a malicious “intent to intimidate” whenever a cross was burned, regardless of the circumstances.

In a previous cross-burning case, R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992), the Court struck down a local ordinance banning hate speech. Writing for the majority in R.A.V., Justice Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) argued that the law engaged in impermissible content and viewpoint discrimination by prohibiting hate speech in the case of some groups while allowing it for others.

Writing for the majority, in Virginia v. Black, Justice O’Connor distinguished the R.A.V. precedent from the present case. She argued that R.A.V. does not prohibit government from banning cross burning in all circumstances. Consistent with this recognition, she applied the “true threats” doctrine of Watts v. United States to cross burning. Under this doctrine, “the speaker need not actually intend to carry out the threat.” The ban on “true threats” seeks to protect individuals from fear of violence and “the disruption that fear engenders.”

Reviewing the history of cross burning, Justice O’Connor concluded that not all cross burning intends to intimidate and terrorize. Sometimes, it conveys a statement of belief or a symbol of group solidarity. In these latter cases, it constitutes protected expression under the First Amendment. Because the prima facie provision of the Virginia statute failed to distinguish between these different manners of cross burning, it ran afoul of the First Amendment. Thus, the Court overturned the conviction of Barry Black, but returned the case of Elliott and O’Mara to the lower court for further action. In sum, cross burning is protected or punishable depending upon the context. Justice Thomas, the Court’s sole African American member, disagreed with Court’s interpretation of the historical record. Thomas argued further that the Virginia law should be upheld because it bans only conduct, not expression.

Source: 538 U.S. 343, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/01-1107.ZS.html.

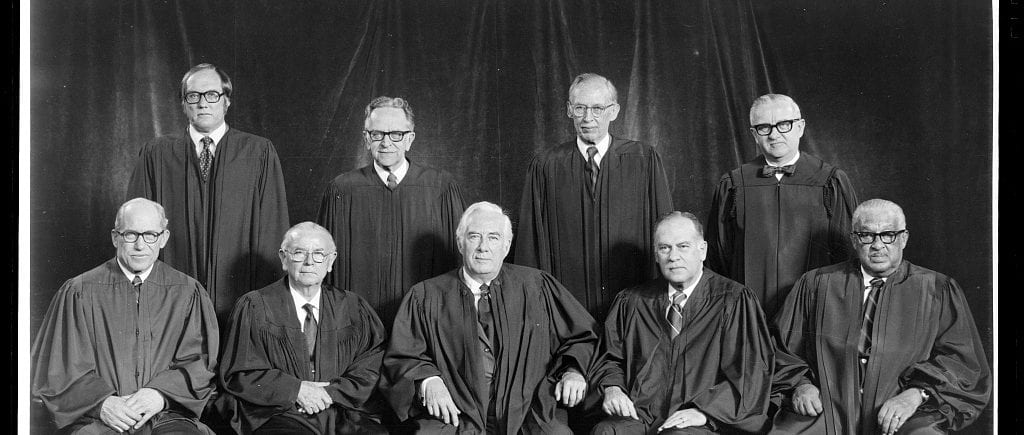

JUSTICE O’CONNOR announced the judgment of the Court and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts I, II, and III, and an opinion with respect to Parts IV and V, in which THE CHIEF JUSTICE, JUSTICE STEVENS, and JUSTICE BREYER join.

In this case we consider whether the Commonwealth of Virginia’s statute banning cross burning with “an intent to intimidate a person or group of persons” violates the First Amendment. We conclude that while a state, consistent with the First Amendment, may ban cross burning carried out with the intent to intimidate, the provision in the Virginia statute treating any cross burning as prima facie[1] evidence of intent to intimidate renders the statute unconstitutional in its current form. . . .

[The Court’s opinion here includes a history of cross burning, from its origins in the fourteenth century as a means for Scottish tribes to signal each other to today’s Ku Klux Klan.]

To this day, regardless of whether the message is a political one or whether the message is also meant to intimidate, the burning of a cross is a “symbol of hate.” And while cross burning sometimes carries no intimidating message, at other times the intimidating message is the only message conveyed. For example, when a cross burning is directed at a particular person not affiliated with the Klan, the burning cross often serves as a message of intimidation, designed to inspire in the victim a fear of bodily harm. Moreover, the history of violence associated with the Klan shows that the possibility of injury or death is not just hypothetical. The person who burns a cross directed at a particular person often is making a serious threat, meant to coerce the victim to comply with the Klan’s wishes unless the victim is willing to risk the wrath of the Klan. Indeed, as the cases of respondents[2] Elliott and O’Mara indicate, individuals without Klan affiliation who wish to threaten or menace another person sometimes use cross burning because of this association between a burning cross and violence.

In sum, while a burning cross does not inevitably convey a message of intimidation, often the cross burner intends that the recipients of the message fear for their lives. And when a cross burning is used to intimidate, few if any messages are more powerful.

The First Amendment, applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, provides that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech.” The hallmark of the protection of free speech is to allow “free trade in ideas”—even ideas that the overwhelming majority of people might find distasteful or discomforting (Abrams v. United States, 1919; see also Texas v. Johnson, 1989:[3] “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable”). Thus, the First Amendment “ordinarily” denies a state “the power to prohibit dissemination of social, economic and political doctrine which a vast majority of its citizens believes to be false and fraught with evil consequence” (Whitney v. California, 1927)[4]. The First Amendment affords protection to symbolic or expressive conduct as well as to actual speech. See, e.g., R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul; Texas v. Johnson, supra; United States v. O’Brien (1968); Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969).[5]

The protections afforded by the First Amendment, however, are not absolute, and we have long recognized that the government may regulate certain categories of expression consistent with the Constitution. See, e. g., Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) (“There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which has never been thought to raise any constitutional problem”). The First Amendment permits “restrictions upon the content of speech in a few limited areas, which are ‘of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.’ ”

Thus, for example, a state may punish those words “which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace” (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire; see also R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, listing limited areas where the First Amendment permits restrictions on the content of speech). We have consequently held that fighting words—”those personally abusive epithets which, when addressed to the ordinary citizen, are, as a matter of common knowledge, inherently likely to provoke violent reaction”—are generally proscribable under the First Amendment (Cohen v. California, 1971; see also Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire).[6] Furthermore, “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a state to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action” (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969).[7] And the First Amendment also permits a state to ban a “true threat” (Watts v. United States, 1969).

“True threats” encompass those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals. See Watts v. United States (“political hyberbole” is not a true threat). The speaker need not actually intend to carry out the threat. Rather, a prohibition on true threats “protect[s] individuals from the fear of violence” and “from the disruption that fear engenders,” in addition to protecting people “from the possibility that the threatened violence will occur.” Intimidation in the constitutionally proscribable sense of the word is a type of true threat, where a speaker directs a threat to a person or group of persons with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death. Respondents do not contest that some cross burnings fit within this meaning of intimidating speech, and rightly so. [T]he history of cross burning in this country shows that cross burning is often intimidating, intended to create a pervasive fear in victims that they are a target of violence. . . .

The prima facie evidence provision, as interpreted by the jury instruction, renders the statute unconstitutional. . . . The prima facie evidence provision permits a jury to convict in every cross-burning case in which defendants exercise their constitutional right not to put on a defense. And even where a defendant like Black presents a defense, the prima facie evidence provision makes it more likely that the jury will find an intent to intimidate regardless of the particular facts of the case. The provision permits the commonwealth to arrest, prosecute, and convict a person based solely on the fact of cross burning itself.

It is apparent that the provision as so interpreted “would create an unacceptable risk of the suppression of ideas” (Members of City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent, 1984). The act of burning a cross may mean that a person is engaging in constitutionally proscribable intimidation. But that same act may mean only that the person is engaged in core political speech. The prima facie evidence provision in this statute blurs the line between these two meanings of a burning cross. As interpreted by the jury instruction, the provision chills constitutionally protected political speech because of the possibility that the commonwealth will prosecute—and potentially convict—somebody engaging only in lawful political speech at the core of what the First Amendment is designed to protect.

As the history of cross burning indicates, a burning cross is not always intended to intimidate. Rather, sometimes the cross burning is a statement of ideology, a symbol of group solidarity. It is a ritual used at Klan gatherings, and it is used to represent the Klan itself. Thus, “burning a cross at a political rally would almost certainly be protected expression” (R.A.V. v. St. Paul). Indeed, occasionally a person who burns a cross does not intend to express either a statement of ideology or intimidation. Cross burnings have appeared in movies such as Mississippi Burning, and in plays such as the stage adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake.

The prima facie provision makes no effort to distinguish among these different types of cross burnings. It does not distinguish between a cross burning done with the purpose of creating anger or resentment and a cross burning done with the purpose of threatening or intimidating a victim. It does not distinguish between a cross burning at a public rally or a cross burning on a neighbor’s lawn. It does not treat the cross burning directed at an individual differently from the cross burning directed at a group of like-minded believers. It allows a jury to treat a cross burning on the property of another with the owner’s acquiescence in the same manner as a cross burning on the property of another without the owner’s permission. To this extent I agree with JUSTICE SOUTER that the prima facie evidence provision can “skew jury deliberations toward conviction in cases where the evidence of intent to intimidate is relatively weak and arguably consistent with a solely ideological reason for burning.”[8]

It may be true that a cross burning, even at a political rally, arouses a sense of anger or hatred among the vast majority of citizens who see a burning cross. But this sense of anger or hatred is not sufficient to ban all cross burnings. As Gerald Gunther has stated, “The lesson I have drawn from my childhood in Nazi Germany and my happier adult life in this country is the need to walk the sometimes difficult path of denouncing the bigot’s hateful ideas with all my power, yet at the same time challenging any community’s attempt to suppress hateful ideas by force of law.”[9] The prima facie evidence provision in this case ignores all of the contextual factors that are necessary to decide whether a particular cross burning is intended to intimidate. The First Amendment does not permit such a shortcut.

For these reasons, the prima facie evidence provision, as interpreted through the jury instruction and as applied in Barry Black’s case, is unconstitutional on its face. . . . [W]e hold is that because of the interpretation of the prima facie evidence provision given by the jury instruction, the provision makes the statute facially[10] invalid at this point. We also recognize the theoretical possibility that the court, on remand,[11] could interpret the provision in a manner different from that so far set forth in order to avoid the constitutional objections we have described. We leave open that possibility. We also leave open the possibility that the provision is severable, and if so, whether Elliott and O’Mara could be retried under [the Virginia law].

With respect to Barry Black, we agree with the Supreme Court of Virginia that his conviction cannot stand, and we affirm the judgment of the Supreme Court of Virginia. With respect to Elliott and O’Mara, we vacate[12] the judgment of the Supreme Court of Virginia, and remand the case for further proceedings.

It is so ordered.

JUSTICE THOMAS, dissenting.

In every culture, certain things acquire meaning well beyond what outsiders can comprehend. That goes for both the sacred, see Texas v. Johnson (1989)[13] (REHNQUIST, C. J., dissenting) (describing the unique position of the American flag in our nation’s two hundred years of history), and the profane. I believe that cross burning is the paradigmatic example of the latter.

Although I agree with the majority’s conclusion that it is constitutionally permissible to “ban . . . cross burning carried out with intent to intimidate,” I believe that the majority errs in imputing an expressive component to the activity in question. . . .

“In holding [the ban on cross burning with intent to intimidate] unconstitutional, the Court ignores Justice Holmes’ familiar aphorism that ‘a page of history is worth a volume of logic’ ” (Texas v. Johnson, 1989).

[Quoting from the majority’s opinion on the history of the Klan:]

“The world’s oldest, most persistent terrorist organization is not European or even Middle Eastern in origin. Fifty years before the Irish Republican Army was organized, a century before Al Fatah declared its holy war on Israel, the Ku Klux Klan was actively harassing, torturing, and murdering in the United States. Today . . . its members remain fanatically committed to a course of violent opposition to social progress and racial equality in the United States.”

To me, the majority’s brief history of the Ku Klux Klan only reinforces this common understanding of the Klan as a terrorist organization, which, in its endeavor to intimidate, or even eliminate, those its dislikes, uses the most brutal of methods. . . .

But the perception that a burning cross is a threat and a precursor of worse things to come is not limited to Blacks. Because the modern Klan expanded the list of its enemies beyond Blacks and “radical[s]” to include Catholics, Jews, most immigrants, and labor unions, a burning cross is now widely viewed as a signal of impending terror and lawlessness. I wholeheartedly agree with the observation made by the Commonwealth of Virginia that: “A white, conservative, middle class Protestant, waking up at night to find a burning cross outside his home, will reasonably understand that someone is threatening him. His reaction is likely to be very different than if he were to find, say, a burning circle or square. In the latter case, he may call the fire department. In the former, he will probably call the police.”

In our culture, cross burning has almost invariably meant lawlessness and understandably instills in its victims well-grounded fear of physical violence. . . .

It strains credulity to suggest that [the Virginia state] legislature that adopted a litany of segregationist laws self-contradictorily intended to squelch the segregationist message. Even for segregationists, violent and terroristic conduct, the Siamese twin of cross burning, was intolerable. The ban on cross burning with intent to intimidate demonstrates that even segregationists understood the difference between intimidating and terroristic conduct and racist expression. It is simply beyond belief that, in passing the statute now under review, the Virginia legislature was concerned with anything but penalizing conduct it must have viewed as particularly vicious.

Accordingly, this statute prohibits only conduct, not expression. And, just as one cannot burn down someone’s house to make a political point and then seek refuge in the First Amendment, those who hate cannot terrorize and intimidate to make their point. In light of my conclusion that the statute here addresses only conduct, there is no need to analyze it under any of our First Amendment tests. . . .

Even assuming that the statute implicates the First Amendment, in my view, the fact that the statute permits a jury to draw an inference of intent to intimidate from the cross burning itself presents no constitutional problems. Therein lies my primary disagreement with the plurality. . . .

Because I would uphold the validity of this statute, I respectfully dissent.

- 1. Latin for “at first appearance,” prima facie refers to something that is seen as true at first sight or is assumed to be true until proven otherwise.

- 2. The respondent is the party against whom a petition is filed, especially one on appeal.

- 3. Abrams v. United States and Texas v. Gregory Lee Johnson.

- 4. Whitney v. California

- 5. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District

- 6. Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire and Cohen v. California

- 7. Brandenburg v. Ohio

- 8. A quotation from the opinion in this case by Justice David Souter (1939–).

- 9. Gerald Gunther (1927–2002) was a legal scholar. This quotation may be found in a discussion of free speech at Stanford Law School, https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/good-speech-bad-speech/.

- 10. On the face of it.

- 11. To remand is to return a case to a lower court for reconsideration.

- 12. To vacate is to cancel a court judgment.

- 13. Texas v. Gregory Lee Johnson.

Grutter v. Bollinger

June 23, 2003

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.