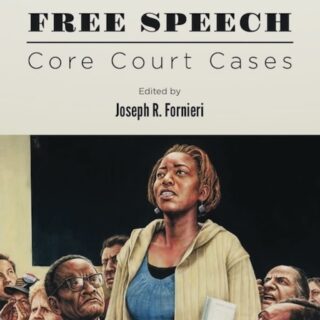

Free Speech: Core Court Cases

The First Amendment, the once Preferred Freedom?

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

—Amendment I. Ratified December 15, 1791

While the language of the First Amendment looks straightforward, its text conceals as much as it reveals. Although “Congress” alone is mentioned, the First Amendment applies to any agent of the national government, including the president. As originally framed, the Bill of Rights guaranteed immunity only from the actions of the federal government, not the states. This changed in the twentieth century with the “doctrine of selective incorporation,” which applied the First Amendment to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause: no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” (See Gitlow v. New York, 1925). The incorporation doctrine authorized the Supreme Court for the first time in its history to review state laws that might infringe upon the First Amendment. Moreover, the liberty guaranteed by the First Amendment should be understood primarily in terms of protection from government control. Thus, it may come as a surprise to some that the First Amendment does not apply to private institutions—those social, political, civil, and religious groups, associations, and corporations that are not units of the federal or state government. So while a state university is bound by the First Amendment, a private college or a religious association may restrict expression as it sees fit in accordance with its own mission statement. A literal interpretation of the word “speech” is likewise misleading, since the Supreme Court has gradually extended the First Amendment to include symbolic, nonverbal expression such as flag-burning, visual imagery such as pornography, commercial communication such as advertising, and children’s entertainment such as video games. Finally, although the First Amendment says “no law,” the right to free speech is not absolute. As Justice Holmes famously said, it does not give one the right “to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater” (Schenck v. United States, 1919). Indeed, one of the enduring issues faced by the Supreme Court has been where to draw the line between protected speech and punishable speech. The goal of this documentary volume of landmark cases is to provide students with the basic texts and tools for understanding the Supreme Court’s evolving jurisprudence on freedom of expression: the First Amendment rights of speech, press, assembly, and association.

Over the past century the First Amendment has attained a preferred place in our constitutional scheme that demands heightened protection by the Supreme Court. In Palko v. State of Connecticut (1937), Justice Benjamin Cardozo (1870–1938) aptly described First Amendment freedoms as “the matrix, the indispensable condition, of nearly every other freedom.” Free speech is essential to democracy for several reasons. First, the expressive acts of speaking, writing, associating, assembling, and dissenting are crucial to the fundamental democratic principle of consent of the governed. Second, freedom of speech and of the press help to ensure the accountability of government and public officials. They expose the darkness of corruption to daylight. Third, free speech functions as a “safety valve” that provides an outlet for dissenting and radical voices to “blow off steam,” as Justice William O. Douglass (1889–1980) eloquently argued in Dennis v. United States (1951). “The airing of ideas releases pressures which otherwise might become destructive.” Indeed, free speech is not only instrumental to democracy, it is valuable as an end in itself, as integral to individual human flourishing and the search for truth. (See Justice Brandeis’ concurrence in Whitney v. California, 1927). Finally free speech advances progress through a competition of ideas that spurs innovation and creativity. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841–1935) made this point in Abrams v. United States (1919), using the metaphor of a marketplace of ideas in which the best ideas slowly win out while archaic notions are abandoned.

As the very lifeblood of democracy, political speech is guaranteed the utmost protection by the Court. Along with other fundamental rights such as the many guarantees of due process, it is awarded an advantage in any legal battle. The landmark First Amendment cases always pit the interest of a governmental authority (national, state, or local) against the dissenting party’s expressive right of speech, press, or association. To help appreciate this clash of interests, consider the image of Lady Justice, the goddess Themis, commonly found in many American courtrooms. She is blindfolded and clasps a sword in one hand and holds up a scale in the other. Her blindfold represents impartiality; the scale, equity; and the sword, the force of law. Given the privileged status of speech in our constitutional scheme, however, her scale will be tipped in favor of the First Amendment. Thus, right from the beginning of the contest, the government faces a burden, an “uphill battle,” if censorship is to prevail over free expression. That is to say, laws that suppress or threaten political speech are subjected to a heightened level of judicial review known as “strict scrutiny.”

Since an understanding of the Court’s jurisprudence requires familiarity with its legal terminology, it will be useful to define some of the key First Amendment concepts readers will encounter throughout these documents. For example, to survive strict scrutiny, a law that infringes upon speech must pass two hurdles. First, the government must demonstrate that the law serves a “compelling purpose” or “end,” such as national security, civil order, or morality. This first hurdle is not too difficult for the government to overcome. Appealing to an implied or expressed constitutional power under state or federal law is usually sufficient. Second, the government must show that the law in question is “narrowly tailored” to achieve its purpose by “the least restrictive means.” This is a higher hurdle. To appreciate “narrow tailoring,” consider the example of a bulky winter jacket. While its “compelling purpose,” or end, is to protect you from cold weather, its means to do so—its excessive size and weight—nonetheless restrict your ability to move and breath freely. Much like being smothered in a large jacket, personal liberty is suffocated by poorly written laws that restrict speech. By contrast, a narrowly tailored jacket not only protects you from the elements, it accomplishes this end through means that allow you to move and breath freely.

The review of “strict scrutiny” along with its requirement of “narrow tailoring” safeguards against two types of infirm laws that consistently menace liberty: “unduly vague laws” whose imprecision forces people of common intelligence to guess at their meaning and application; and “overly broad laws” that sweep too expansively in burdening protected speech along with unprotected speech. The modifiers “unduly” and “overly” are important recognitions of the fact that all language contains some degree of vagueness and ambiguity. Contrary to those who expect mathematical certainty in jurisprudence, the law will always have some “gray area.” Hence the cliché that jurisprudence is more an art than a science. Notwithstanding this inherent ambiguity, however, “unduly vague” and “overly broad” laws confer too much discretion upon authorities to abuse power in an arbitrary manner through ever-changing and unpredictable definitions. Unpopular views can be more easily suppressed under the pretext of generalized claims of “public order.” Returning to the Lady Justice metaphor, overly broad and unduly vague laws tilt her scale in favor of the authority and shift the burden of proof onto the dissenter, who is tasked with overcoming the state’s interest. To make thing worse, the very threat of punishment from these laws creates the notorious “chilling effect” that induces self-censorship. Fearing repercussions for speaking out, people choose to remain silent.

If free speech is to perform its vital function in serving democracy, it should be exercised fearlessly, not timidly. If citizens are to debate controversial issues forthrightly rather than holding their peace in festering silence, they must do so with the confidence that their expression will not be investigated or punished by authorities. To prevent this chilling effect, the Supreme Court requires ample “breathing room” for free speech. Put another way, it errs in protecting “too much” expression rather than “too little Consequently, the First Amendment tolerates offensive, feared, disturbing, and even some hateful speech (See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan and Matal v. Tam). Indeed, a core principle of First Amendment interpretation today is that authorities may not bar expression simply because they find it offensive, disturbing, or disagreeable.

Once laws have passed strict scrutiny, under what circumstances may government permissibly restrict speech? When does speech “cross the line” between protected and punishable expression? Under current First Amendment law, the government may punish speech only in the case of an emergency when it can demonstrate a tight causal connection or nexus between the speech and an immediate harmful effect(Justice Holmes’ dissent in Abrams; Justice Brandeis’ concurrence in Whitney). Undifferentiated fear of some possible, remote harm is not sufficient to warrant restriction. Under current First Amendment law, the government can restrict speech only in the case of an emergency, for example, a direct incitement to “imminent lawless action” (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969).

Though words certainly have the capacity to harm and hurt, the importance of protecting speech likewise outweighs the government’s interest in protecting citizens from emotional harm. The First Amendment does not protect one’s feelings. As Chief Justice John Roberts (1955–) explained in the controversial case of Snyder v. Phelps (2011): “As a nation we have chosen . . . to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.” A different decision in this case that would have given greater weight to the emotional pain inflicted by speech would have constituted a major departure from the Court’s jurisprudence, which has consistently underscored that “a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger” (see Terminiello v. Chicago, 1949). Because feelings are highly subjective, they elude clear legal specification. Indeed, what would remain of free speech if it was subject to the objections of the most thin-skinned among us?

In addition to the key concepts of “preferred freedom,” “strict scrutiny,” “narrow tailoring,” “undue vagueness,” “overbreadth” and “chilling effect,” the fundamental principle of “viewpoint” or “content neutrality” must be added to the list of key First Amendment concepts. Viewpoint neutrality prevents government from restricting speech on the basis of its content, message, or idea, and from favoring one viewpoint or side of a debate over another. This crucial concept explains why the First Amendment provides shelter to social justice activists and racists alike. Justice Holmes, whose thought dominated the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on the First Amendment, went so far as to say: “If there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought—not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate” (United States v. Schwimmer, 1929).

With all due respect to Justice Holmes, why shouldn’t certain messages be banned from public discourse? Why should we tolerate intolerant speech? Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels infamously maintained that a lie repeated often enough would eventually be accepted as true. Perhaps certain kinds of speech should be suppressed to prevent falsehood and lies from winning out in the marketplace of ideas. Indeed, history also reveals that people are swayed by base emotions and stirred by demagogic appeals. Perhaps censorship could have prevented the genocides of the twentieth century.

While there are certainly risks involved in tolerating false, offensive, and even hateful speech, the current view of the First Amendment is that the benefits of free speech outweigh the societal costs of censorship. In a passage often cited by the Court, Justice Robert H. Jackson (1892–1954) defended the principle of viewpoint neutrality in these weighty terms: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein” (West Virginia v. Barnette, 1943). In sum, the First Amendment forbids the government from favoring any public orthodoxy, however well intentioned. In Texas v. Johnson (1989), for example, the Court decided that the state law punishing flag desecration was unconstitutional because it favored a message of patriotism over a disfavored message of contempt. In other words, the Texas law impermissibly engaged in viewpoint discrimination. However abhorrent speech may be, the state cannot take sides in the marketplace of ideas by favoring one message over another through censorship.

The cases in this volume are arranged thematically. For example, they trace the development and evolution of the “clear and present danger” test from Schenck through the controlling precedent of Brandenburg and its “imminent lawless action” test. In the following decades, the Court expanded free speech to include symbolic expression of flag burning in Texas v. Johnson and cross burning in Virginia v. Black (2003). As noted, the Court has underscored that the First Amendment protects offensive, disturbing, and feared speech. This is clearly seen in Cohen v. California (1971) and Matal v. Tam (2017). In Snyder v. Phelps the Court preferred free speech over the claims of emotional distress.

The right to liberty of the press is represented by a number of cases, including Near v. Minnesota (1931) and New York Times v. United States (1971). Because freedom of association to unite and advocate with others is a fundamental right implicit in the First Amendment, the volume includes the important precedents of NAACP v. Alabama (1958), Boy Scouts v. Dale (2000), and Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984).

This volume also explores those categories of unprotected speech that have traditionally been considered to lie outside of the First Amendment: libel (Times v. Sullivan, 1964), obscenity (Miller v. California, 1973), and fighting words (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942). Failed efforts to expand these unprotected categories to “group libel” and violent video games for children are seen in the respective cases of Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952) and Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2011). The Supreme Court’s first attempt to regulate the Internet as a “dramatic expansion of [a] new marketplace of ideas” is seen in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (1997).

The Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence recognizes a hierarchy of speech that runs the gamut from the heightened protection of political speech to reduced protection of commercial and broadcast speech. Its consideration of lower-value commercial and broadcasting speech is thus seen in the respective cases of Central Hudson Gas & Electric v. Public Service Commission (1980) and FCC v. Pacifica (1978). Finally, the topic of the First Amendment in the educational setting is represented by the cases of Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986), and Morse v. Frederick (2007). Campaign finance is notably absent. Protected under the First Amendment in the landmark case of Buckley v. Valeo (1976) and extended to corporations in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), campaign finance is too complex a topic, we thought, for inclusion in this volume.

In conclusion, while these landmark cases contain many pearls of wisdom about free speech, history teaches us that we cannot always rely on the Court to safeguard our liberties. The Court’s decisions may be side-stepped or ignored. The Bill of Rights is only a parchment paper unless supported by habits of heart and mind that give it life. Indeed, free speech can only be preserved through a “First Amendment culture” that understands, cherishes, and jealously guards its preferred place in our democracy. This volume hopes to contribute in some small way to that worthy cause.

Illegal Advocacy

- Schenck v. United States 1919. The first and most notable landmark Supreme Court case on free speech. Justice Holmes first articulated the clear and present danger standard. The case also included his oft-repeated metaphor that the First Amendment does not guarantee one the right to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater.

- Abrams v. United States, 1919. Holmes shifted his position on the First Amendment to become, along with Justice Brandeis, one of “the Great Dissenters.” Holmes’ dissent refined the clear and present danger test to be more protective of speech by including the criterion of “imminence” or immediacy. His dissent also made use of the “free trade of ideas” metaphor, which has become the Court’s dominant rationale for the role of free speech in democracy.

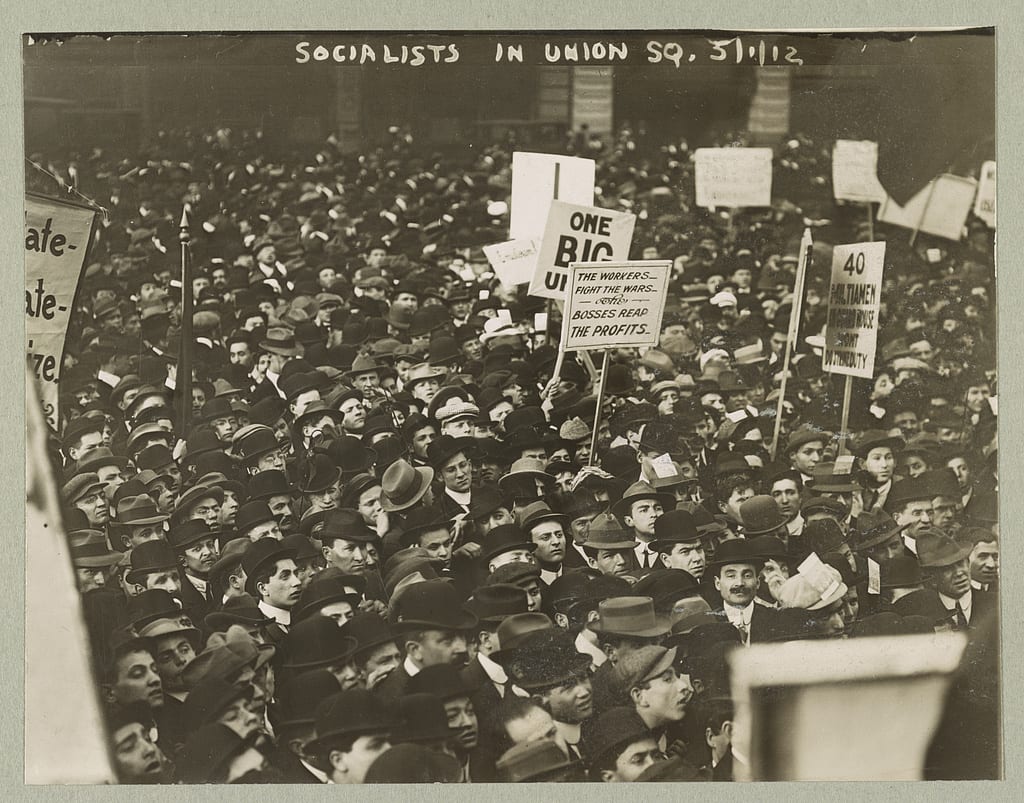

- Gitlow v. New York, 1925. A case that applied the First Amendment to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s liberty clause. In his dissenting opinion, Holmes famously declared that “every idea is an incitement”—that is to say, speech should not be restricted unless it presents some imminent threat under the circumstances. Holmes’ dissent anticipated the Court’s later distinction between advocacy of action versus advocacy of ideas.

- Whitney v. California, 1927. Prosecution of prominent social activist and heiress Charlotte Whitney under California criminal syndicalism law. Brandeis’s concurring opinion included one of the most profound justifications of the function of free speech in a democratic society ever written. His civic virtue rationale of free speech may be contrasted to Holmes’ more libertarian free market view.

- Dennis v. United States, 1951. One of the trials of the century during the height of the Cold War. Dennis was the secretary general of the Communist Party of America. The Court modified the clear and present danger test and adopted the more repressive standard of “clear and probable” danger to uphold his conviction under the Smith Act. The precedent has been narrowed considerably by later decisions that are more protective of speech.

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969. The controlling precedent governing illegal advocacy. The case involved the threatening and racist language of a Ku Klux Klansman caught on film. The Court refined the clear and present danger test so that direct incitement must involve “imminent lawless action” and the likelihood of “steeling others into such action,” a high burden that is very protective of speech. Symbolic and Offensive Speech

Symbolic and Offensive Speech

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942. Justice Jackson articulated the controversial “fighting words” doctrine that restricts “ low value speech.” Though the doctrine has since been narrowed significantly, there have been efforts to revive it, along with the group libel doctrine in Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952), as a basis for restricting offensive speech on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.

- Beauharnais v. Illinois, 1952. This case is an example of group libel, the punishment of speech that defames groups of people based on race, creed, color, or sex. Using the ad hoc self-restraintist balancing test, Justice Frankfurter upheld the Illinois group libel law. Though still on the books, Beauharnais has been eviscerated by subsequent opinions such as Brandenburg v. Ohio, Cohen v. California, Texas v. Johnson, and Virginia v. Black. Some critics of the Court’s commitment to the principle of viewpoint would like to create a First Amendment content-based exception for group libel as a means to protect minority groups from offensive speech that demeans their equal status in society. Before so doing, however, it is worthwhile to consider the dissents of Justice Douglas and Justice Black in this case.

- Cohen v. California, 1971. An important and controlling precedent governing offensive symbolic speech. The Court struck down a California public decency law that punished Cohen for wearing a jacket in a Court house with “F——— the Draft” scrawled on t he back of it. Justice Harlan famously said that “one man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric.” The Court fully embraced the principle of content neutrality in regard to speech. Critics like Justice Robert Bork (1927–2012) see this case as contributing to the coarsening of American society.

- Texas v. Johnson, 1989. Extended First Amendment protection of symbolic speech to flag burning. Citing the Terminiello precedent, Justice Brennan argued that the First Amendment serves its highest function when it “invites dispute, creates a condition of unrest, and dissatisfaction” with the status quo. By favoring patriotic expression while punishing scornful expression about the flag, Texas engaged in impermissible viewpoint-content discrimination.

- Virginia v. Black, 2003. The Court combined two instances of cross burning that were punished under the prima facie provision of Virginia law: a peaceful Klan membership rally at a private residence that was in view of the public highway, and an incident where two juveniles drove a truck into their African American neighbor’s yard and then burnt a cross on the lawn. Following the principle of viewpoint-content neutrality, the Court extended symbolic speech protection to the burning of the cross in the first case of the Klan rally. Under the different circumstances of the second case, however, cross burning could be banned as a “true threat” without violating the First Amendment. The Court’s “true threat” doctrine is now the controlling doctrine in terms of threatening, harassing, or intimidating speech. Justice Thomas’ dissent is noteworthy.

- Snyder v. Phelps, 2011. The infamous Westboro Baptist Church case involved an offensive demonstration at a Marine’s funeral by members of the Westboro Baptist Church, who believed that God was justly punishing the country for allowing gays in the military. Although Snyder was not gay, followers of the Church staged a protest at his funeral that included signs like “God hates fags.” After the funeral, Snyder’s father viewed the demonstration on TV and sued, recovering millions of dollars in damages for emotional distress. The Court reversed, upholding the right of the Westboro members to express their views, however repugnant and offensive, because the demonstration occurred in a “public forum” and was therefore entitled to heightened protection. Justice Alito’s stinging dissent is noteworthy.

- Matal v. Tam, 2017. This most recent free speech case involved the effort of Simon Tam, the leader of an Asian American punk rock band, The Slants, to trademark his band’s name. Fully embracing the derogatory racial connotation of the name, Tam wanted to “reclaim” the term by draining its power. He was denied a trademark under the disparagement clause of the Lanham Act of 1946, which prohibits trademarks that “[consist] of or [comprise] immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter; or matter which may disparage or falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute.” In a rare unanimous decision with far-reaching implications for the protection of offensive speech based on race, gender, or ethnicity, the Court struck down the disparagement clause as a violation of the First Amendment.

Press

- Near v. Minnesota, 1931. The first landmark Supreme Court case involving freedom of the press. A scurrilous anti-Semitic paper that accused state officials of colluding with organized crime was closed down by a public nuisance “gag law” against anyone engaged in publishing or circulating “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” or “malicious, scandalous and defamatory” material. The Supreme Court overturned the permanent injunction on grounds of prior restraint. Justice Hughes provided a concise overview of freedom of the press from the time of the Founding and its needed public service as a watchdog to sniff out corruption.

- New York Times v. Sullivan, 1964. The momentous freedom of press case that overturned a libel prosecution against the New York Times for factually inaccurate claims about the abuse of civil rights activists by Alabama authorities. In the case of public figures like Police Commissioner Sullivan, the Court developed the “actual malice” test that places a high burden on them to win libel cases against their critics, even if critics’ opinions involve falsehoods and mistaken facts.

- New York Times v. United States, 1971. The famous Pentagon Papers case that struck down as an illegal prior restraint the Nixon’s administration’s effort to suppress publication of the incriminating document about the Vietnam War in the interest of national security. Applying the preferred freedom test, the Court tilted the balance in favor of First Amendment unless a “compelling” interest can outweigh it.

- Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972. The case provides a clear example of the conflict between the rights of free speech and due process. After reporting on drug manufacturing and use in Louisville, Kentucky, Branzburg was ordered to testify before a grand jury. He refused, claiming that the First Amendment granted him a privilege as a reporter to remain silent about his sources. The Court disagreed and ruled that the First Amendment does not guarantee such a privilege. The state’s interest in due process and criminal investigation outweighed the reporter’s claim to immunity from grand jury testimony on First Amendment grounds.

Association

- NAACP v. Alabama, 1958. An important civil rights and First Amendment case. On the grounds of freedom of association, the Court protected the right of the NAACP to deny the state of Alabama its membership list.

- Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 1984. The Minnesota chapter of the Jaycees admitted women as full members of their organization contrary to the policy of the national organization. The state of Minnesota then brought discrimination charges against the national Jaycees for excluding women. The Court unanimously ruled in favor of Minnesota. In this particular case, the state’s compelling interest in preventing discrimination outweighed the Jaycees’ claim to freedom of association.

- Boy Scouts v. Dale, 2000. James Dale was an openly gay activist who was dismissed as a scoutmaster because his views were inconsistent with the Boy Scout’s values. Dale sued under a New Jersey accommodations law that prohibited discrimination in public places on the basis of sexual orientation. The Boy Scouts claimed that this law did not apply because it was a private organization. The Court ruled 5-4 in favor of the Boy Scouts’ freedom of association.

Educational Setting

- Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969. Perhaps the most famous landmark decision in the educational setting. The Court extended symbolic speech in the classroom to the peaceful wearing of black armbands by students to protest the Vietnam War. Justice Black wrote a stinging dissent warning that the decision would undermine discipline in secondary education. Though it is still on the books, the Court narrowed this ruling in subsequent cases.

- Bethel v. Fraser, 1986. Narrowed the Tinker precedent. At an assembly of around six hundred secondary-school students, Matthew Fraser delivered a speech filled with sexual inuendo and double entendre. He claimed that this speech was protected under the First Amendment, but the Court disagreed, giving high school administrators more leeway to discipline unfavorable messages in the educational setting.

- Morse v. Frederick, 2007. The most recent case governing free speech in the educational setting. During an Olympic Torch Relay procession in Juneau, Alaska, Frederick unfurled a banner that read “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS” at an official school event. Justice Roberts decided that the pro-drug message was not protected by the First Amendment. Along with Bethel, Morse has narrowed the Tinker precedent.

Broadcasting and Commercial Speech

- Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation, 1978. The case involving comedian George Carlin’s infamous “Filthy Words” monologue—words “you couldn’t say on the public airwaves.” After hearing the routine on the radio, a concerned father complained to the FCC, which sent the Pacifica Foundation a letter of reprimand threatening future punishment. The Court ruled in favor of the FCC, thereby permitting them to limit the time, place, and manner of broadcasting. According to Justice Stevens, “of all forms of communication, it is broadcasting that has received the most limited First Amendment protection.”

- Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corporation v. Public Service Commission, 1980. A landmark commercial speech case. Although commercial speech, like broadcasting, is afforded less First Amendment protection than political speech, it prevailed in this case over New York State’s interest in encouraging energy conservation. Writing for the majority, Justice Powell developed a four-part test for judging the First Amendment boundaries of commercial speech. Since the ban on advertising remained in place after the energy crisis had passed, the state’s interest in energy conservation was not sufficiently warranted under this four-part test.

Obscenity, Violent Video Games, the Internet

- Miller v. California, 1973. The controlling precedent on obscenity that replaced Roth v. United States, 1957. The new obscenity standard of Miller was a state and local standard, not a national one, as under Roth. The Court also replaced the “utterly without redeeming social value” of the Memoirs test with the SLAPS test (serious, literary, artistic, political, scientific value).

- Brown v. Entertainment, 2011. Extended First Amendment protection to violent video games for minors. Writing for the majority, Justice Scalia argued that studies did not prove a direct link between viewing violent videos and violent behavior. He argued further that the long-standing tradition of violent depictions in children’s literature prevent carving out a new content-based exception to the First Amendment that would bar violent video games for minors.

- Reno v. ACLU, 1997. The Supreme Court’s first foray into the brave new world of the Internet. It struck down the Communications Decency Act, whose aim of protecting children could have been achieved through less restrictive means that did not infringe upon protected speech of adults. The Court’s recognition of the Internet as a “dramatic expansion of [a] new marketplace of ideas” helps to explain why it preferred free speech in this case.

For each of the documents in this collection, we suggest questions relevant for that document alone (questions A) and questions that require comparison between documents (questions B).

1. Schenck v. United States (1919)

A. What was the Espionage Act? What is the “clear and present danger” test? How does this test emphasize the context and circumstances of the speech? Why do you think it took so long for the Supreme Court to come up with a standard for judging the First Amendment? Do you think Schenck’s speech should have been protected under the First Amendment? According to Justice Holmes, what was it about Schenck’s speech that constituted a clear and present danger under the circumstances?

B. Compare Justice Holmes’ use of the clear and present danger test in Schenck to his use of it in Abrams. How did Justice Brandeis elucidate the “clear and present danger” test in Whitney v. California? Would Schenck’s speech be protected under current First Amendment jurisprudence in Brandenburg v. Ohio?

2. Abrams v. United States (1919)

A. What test or standard did Justice Clarke use in Abrams? Do you think the Court’s decision was biased against the defendants because they were immigrants and radicals? How does Holmes’ dissent clarify the meaning of the “clear and present danger” test? Explain Holmes’ “free trade in ideas” metaphor. What are some of the metaphor’s strengths and weaknesses? Are there significant differences between the marketplace of consumer goods and the marketplace of ideas? What did Holmes mean when he said that “time has upset many fighting faiths”? To what extent was Holmes’ metaphor influenced by Social Darwinism?

B. According to Justice Holmes, how did the facts and circumstances in Abrams differ from those of Schenck? Do you think Justice Holmes’ dissenting opinion in Abrams consistent with his reasoning in the previously decided cases of Schenck, Frohwerk, and Debs?

3. Gitlow v. New York (1925)

A. What was the historical context of Gitlow v. New York? What is “criminal anarchy”? To what extent do you find the New York criminal anarchy law overly broad and unduly vague? What is the “doctrine of incorporation”? How is it relevant to Gitlow? What is the “bad tendency” test? How did Justice Sanford combine elements of the bad tendency test and self-restraintist balancing test? How did Justice Holmes’ dissenting opinion help to clarify the “clear and present danger” test? What did Holmes mean when he said, “Every idea is an incitement. It offers itself for belief, and, if believed, it is acted on unless some other belief outweighs it or some failure of energy stifles the movement at its birth.” Do you agree?

B. Compare Justice Holmes’ use of the clear and present danger test in Schenck, Abrams, and Gitlow. Compare the bad tendency test in Gitlow to the clear and present danger test Holmes used in Abrams and Gitlow. What are the similarities between the New York criminal anarchy law in Gitlow and the Espionage Act?

4. Whitney v. California (1927)

A. What is “criminal syndicalism”? What test or standard did Justice Sandford use to decide the case? What test should have been used according to Brandeis and Holmes? How did Justice Brandeis’s opinion defend free speech as both a means to self-government and an end that is integral to human flourishing? What were Justice Brandeis’s “emergency” criteria for the restriction of speech? Why do you think Brandeis and Holmes concurred even though their opinion sounds more like a dissent?

B. Compare and contrast Brandeis’ view of free speech in Whitney to Justice Holmes’ “marketplace of ideas” metaphor in Abrams. Compare and contrast the California criminal syndicalism law in Whitney to the New York criminal anarchy law in Whitney. What ends or purposes did these state laws seek to accomplish?

5. Near v. Minnesota (1931)

A. Under what law was Near prosecuted? Do you think this law was overly broad and unduly vague? What is prior restraint? Do you think Near’s anti-Semitic remarks should have been protected under the First Amendment? To what extent were the newspaper’s allegations about corruption and organized crime in Minneapolis true? How did Minnesota engage in prior restraint? Do you agree with Hughes that “the fact that the liberty of the press may be abused by miscreant purveyors of scandal does not make any the less necessary the immunity of the press from previous restraint in dealing with official misconduct”? According to Hughes, what is the role of a free press in a democratic society? To what extent has the press today lived up to or fallen short of this standard? Discuss Justice Butler’s dissent. Do you agree with him or Hughes?

B. Compare the different functions of free speech in Near, Whitney, and Abrams. Compare and contrast the prior restraint in Near to that of New York Times. Compare the Court’s view of the Founders’ view of the First Amendment in Near with that of the New York Times. Compare and contrast the state’s interest in Near with the federal government’s interest in New York Times.

6. Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942)

A. Do you think Chaplinsky’s speech should have been protected? What does it mean to say that speech has “no essential part of any exposition of ideas”? How does the “fighting words” doctrine reveal a hierarchy of speech? Do you think the “fighting words” doctrine should be expanded to include “hate speech” as a separate category of unprotected speech? Should the “fighting words” doctrine be expanded in the interest of civility?

B. Explain how the “fighting words” doctrine has been narrowed by Cohen v. California, Texas v. Johnson, and Snyder v. Phelps. Compare and contrast the “fighting words” doctrine in Chaplinsky to the “true threats” test in Virginia v. Black.

7. Dennis v. United States (1951)

A. What was the historical context of the Dennis case? What is the difference, if any, between “conspiracy to advocate overthrowing the government” and “conspiring to overthrow the government”? Do you think that Dennis’ speech constituted a “clear and present danger” as understood by Justices Holmes and Brandeis? What is the “clear and probable” danger test? How did Justice Vinson modify the clear and present danger test? Why did Justice Black consider this a case of “prior restraint”? How does Justice Douglas’ characterization of the facts and circumstances in the case differ from that of the majority? What standard or test would Douglas have used? Explain Justice Douglas’ statement that “free speech has occupied an exalted position because of the high service it has given our society.”

B. Compare Vinson’s clear and probable danger test to Holmes’ and Brandeis’ clear and present danger test in Abrams and Whitney. Compare Justice Frankfurter’s use of the self-restraintist balancing test in Dennis to Justice Sanford’s use of it in Gitlow v. New York.

8. Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952)

A. What is “group libel”? How is it similar to and different from individual libel? Should the Court recognize a First Amendment exception for “group libel,” as it has for the unprotected categories of “libel,” “fighting words,” and “obscenity”? What would be the costs and benefits of doing so? How would “group libel” be defined? What groups would be included or excluded? Why did Justice Black think Frankfurter’s reliance on Chaplinsky was “misplaced”? What did Justice Douglas mean when he said that the First Amendment is “couched in absolute terms”? Do you agree? What are some exceptions to this absolutist view? Do you agree with Douglas’ “slippery slope” argument: “Today a white man stands convicted for protesting in unseemly language against our decisions invalidating restrictive covenants. Tomorrow a Negro will be hauled before a court for denouncing lynch law in heated terms.”

B. How did Frankfurter rely upon the precedent of Chaplinsky? How are the doctrines of “fighting words” in Chaplinsky and group libel in Beauharnais content-based restrictions? Compare the Illinois group libel law in Beauharnais to the actual malice test in New York Times v. Sullivan. How has Beauharnais been emasculated by Brandenburg v. Ohio and Virginia v. Black?

9. NAACP v. State of Alabama (1958)

A. What was the historical context of NAACP v. Alabama? How was this a landmark civil rights and First Amendment case? What is freedom of association? How is it implicit in the First Amendment? What was Alabama’s interest in obtaining the disclosures? How did Alabama’s “production order” for the NAACP infringe upon the organization’s freedom of association?

B. Compare the state interest of Alabama in NAACP v. State of Alabama with that of California in Whitney v. California. In regard to the doctrine of incorporation, distinguish the Court’s judicial activism in NAACP from that in Gitlow v. New York. What would justify the Court’s activism in either or both cases?

10. New York Times v. Sullivan (1964)

A. What is the actual malice test? What is the reckless disregard of truth? How was Sullivan’s status as a “public official” relevant to Brennan’s opinion? Do you think that journalists should be held responsible for “factual inaccuracies” if they harm someone’s reputation? Do you think Times v. Sullivan should be overturned or narrowed in the interest of civility and truth? Has Times v. Sullivan contributed to “fake news” on both sides of the aisle?

B. Compare the group libel law in Beauharnais with the Court’s definition of libel of public officials in Times v. Sullivan.

11. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969)

A. Do you think the classroom was the appropriate setting for Tinker’s protest? How did Justice Fortas’ and Justice Black’s characterizations of the facts differ in this case? How is this case an example of the preferred freedom standard? How did Fortas apply the precedent of Burnside v. Byars? Do you agree with Justice Black’s dissent? Did the Tinker precedent undermine school discipline and usurp the authority of local schoolboards?

B. How has the Tinker precedent been narrowed subsequently? What are some of the key precedents in the educational setting that have narrowed it? Can you distinguish the facts in each of these cases?

12. Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

A. Why do you think the Court issued a per curiam in this case? What was the “imminent lawless action” test announced in Brandenburg? Do you think the imminent lawless action test is unrealistic by allowing advocacy right up to the brink of violent action? Do you think Brandenburg’s speech should have been punished? How was Brandenburg’s conditional language relevant to the Court’s reasoning?

B. How does the imminent lawless action test constitute a refinement and/or evolution of the clear and present danger test in Schenck, Abrams and Whitney? Why did the Court overturn Whitney v. California?

13. Cohen v. California (1971)

A. What were the conflicting interests in this case? According to Justice Harlan, why didn’t Cohen’s speech fit into any of the unprotected categories? Do you agree with Justice Harlan that “it is nevertheless often true that one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric”? How is Harlan’s opinion an example of the preferred freedom view of the First Amendment? What do you think of Harlan’s statement that if people wanted to avoid further bombardment from Cohen’s offensive message they could have done so by simply “averting their eyes”? Explain Harlan’s statement that “governments might soon seize upon the censorship of particular words as a convenient guise for banning the expression of unpopular ideas.” Do you agree? Do you think that the precedent of Cohen v. California has debased public discourse and civility?

B. Compare Justice Murphy’s view of a hierarchy of speech in Chaplinsky with Justice Harlan’s more relativistic view in Cohen. How did Harlan apply the precedent of Brandenburg v. Ohio in this case?

14. New York Times Co. v. United States (1971)

A. Do you think the Pentagon Papers should have been leaked to the newspapers? What different interests did the Court have to balance in this case? How is this case an example of the preferred freedom doctrine? Why do you think the Court decided this case so quickly? Explain Justice Blackmun’s dissent. What test or standard did he use?

B. Compare the prior restraint in New York Times with that of Near v. Minnesota. What are the different government interests in each case? How do both cases invoke the Founders on liberty of the press? Are the two views of the Founders consistent with each other?

A. What were the facts and circumstances of this case? What rights and interests were weighed against each other? What “privilege” did Branzburg claim? On what grounds did Justice White reject this claim to privilege? Do you think reporters should have the privilege Brannzburg claimed? Explain Justice Douglas’ dissent. Why did he think the decision would harm freedom of the press?

B. Why was the press afforded less protection in Branzburg than in New York Times v. Sullivan? How did Justice White distinguish Branzburg from other precedents involving freedom of the press?

16. Miller v. California (1973)

A. What is obscenity? What is meant by “prurient interest”? What is the difference between sexuality and obscenity? What was the Hicklin test? Why is obscene speech not protected by the First Amendment? What is the definition of “obscenity” in Miller? How does the SLAPS test in Miller provide more guidance to juries than the “utterly without redeeming social value” test in Memoirs? How does Justice Burger’s opinion in Miller reflect the principle of federalism? What are the precedents of Paris Adult Theatre v. Slaton (1973), and New York v. Ferber(1982)?

B. Compare Roth v. United States and Miller v. California. How are fighting words in Chaplinsky and obscenity in Miller both examples of content-based restrictions of speech? Do you agree with these exceptions? How do these content-based restrictions differ from the context-based test in Brandenburg?

17. Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978)

A. What are some of the content-based restrictions Justice Stevens mentioned in the beginning of his opinion? According to Justice Stevens, what important differences are there between broadcast speech and other kinds of speech? Explain how “each medium of expression presents special First Amendment problems.” Did the Court restrict George Carlin’s speech on the basis of its content, its context, or both? To what extent was Carlin’s speech restricted on the basis of its “time, place, and manner”?

B. How did the Court apply the Miller precedent in FCC? Was Carlin’s speech obscene under the Miller test?

18. Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corporation v. Public Service Commission (1980)

A. What are the conflicting interests in this case? What important commercial speech precedents did the Court cite? Why do you think commercial speech is entitled to less First Amendment protection than political speech? Do you agree? What was Justice Powell’s four-part test for commercial speech in Central Hudson?

B. Compare commercial speech in this case with political speech in Snyder v. Phelps. To what extent does the Court’s view of commercial speech in this case accord with Justice Murphy’s view of a hierarchy of speech in Chaplinsky?

19. Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984)

A. Why do you think this decision was unanimous? How did Justice Brennan affirm the right to freedom of association under the First Amendment? How did the Court weigh freedom of association against antidiscrimination law? What are the different kinds of associations Justice Brennan described? Explain his statement: “Between these poles, of course, lies a broad range of human relationships that may make greater or lesser claims to constitutional protection from particular incursions by the state.” Why are some associations entitled to more protection than others? Do you agree? What “features” of the Jaycees did not warrant the heightened protection of other kinds of associations?

B. Compare Brennan’s reasoning in Roberts with Rehnquist’s opinion in Boy Scouts v. Dale. Compare the Court’s opinion in NAACP with Roberts. Why did the claim of association prevail in NAACP but not in Roberts? Do you agree?

20. Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986)

A. Why are the rights of students in the educational setting “not automatically coextensive” with those of adults? How was Fraser’s speech “inconsistent with the “fundamental values” of public school education”? What are these “fundamental values”?

B. How did the Court apply the Tinker v. Des Moines precedent in Bethel? Did Fraser’s speech “materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” under Tinker? To what extent does Bethel narrow Tinker? What are the differences between Tinker’s and Fraser’s speech? Compare the Court’s reasoning in Bethel with that in Tinker and Morse. What accounts for the different rulings in these cases?

21. Texas v. Johnson (1989)

A. What is symbolic speech? Is it literally mentioned in the First Amendment? Should it be entitled to the same protection as other kinds of speech? What was the O’Brien test, and how did Justice Brennan apply it in Texas v. Johnson? What was Texas’ interests in punishing flag desecration? Explain how Justice Brennan made use of the preferred freedom test in this case. Do you agree with Justice Brennan’s statement: “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable”? How compelling are the dissents of Justices Rehnquist and Stevens? Why did Rehnquist invoke poetry?

B. How did the Court use the precedents of Brandenburg and Chaplinsky in this case? Compare and contrast the Court’s opinion on flag burning in Texas with cross burning in Virginia v. Black.

22. Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (1997)

A. What was the state’s interest in this case? How was the CDA “unduly vague”? How could it have achieved its end through “less restrictive means”? To what extent has the Internet led to a “dramatic expansion of [a] new marketplace of ideas”? What are some of the challenges that the Internet poses to the First Amendment? Do you think there should be greater censorship of inappropriate material on the Internet for children?

B. Explain how Justice Stevens distinguished Reno from the precedents of Ginsberg v. New York, Miller v. California, and FCC v. Pacifica.

23. Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000)

A. How did the Boy Scouts engage in “expressive activity”? According to Chief Justice Rehnquist, how is the Boy Scouts’ mission reflected in the organization’s oath? What interest did the New Jersey accommodations law advance? How did Rehnquist apply the precedent of Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston (1995)? How does “Forcing a group to accept certain members . . . impair the ability of the group to express those views”? To what extent did the Court decide in favor of the Boy Scouts because they were a private group? Why is it important to protect private groups from government intrusion if those groups discriminate? Can you think of examples of other groups or associations that exclude membership on the basis of a person’s practices and/or beliefs? Is this discriminatory? Explain Justice Steven’s dissent.

B. How did Rehnquist apply the precedent of Roberts v. United States Jaycees? Compare the Court’s view of freedom of association in NAACP with Boy Scouts. Is the Court’s view consistent?

24. Virginia v. Black (2003)

A. What is the “prima facie” provision of the Virginia cross-burning statute? What, according to Justice O’Connor, was problematic about the prima facie provision? What is the basis for Justice O’Connor’s distinction between different kinds of cross burnings? What is the “true threats” doctrine? Do you agree that the “speaker need not actually intend to carry out the threat”? Explain Justice Thomas’s dissent. Do you agree with him? Why did he consider cross burning “conduct” and not speech? How does his interpretation of the history of the Ku Klux Klan differ from Justice O’Connor’s?

B. Compare the “true threats” doctrine in Virginia v. Black with the “imminent lawless action test” in Brandenburg. Compare the “fighting words” doctrine in Chaplinsky with the “true threats” doctrine. How might the precedent of Beauharnais v. Illinois have been used to decide this case differently?

25. Morse v. Frederick (2007)

A. Do you think Frederick’s message on the banner was entitled to First Amendment protection? What are the conflicting interests in this case? How did the school setting influence the Court’s reasoning in this case? To what extent did Frederick’s pro-drug message influence Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion? Explain Justice Stevens’ dissenting opinion. Do you agree? Explain Justice Thomas’ dissenting opinion.

B. How have the precedents of Bethel v. Fraser and Morse v. Frederick narrowed Tinker v. Des Moines? How do the facts of these cases differ? Was the Court’s reasoning in Frederick consistent with Tinker, or do you agree with Justice Thomas that Tinker should be overturned?

26. Snyder v. Phelps (2011)

A. How did the political content of Westboro Baptist’s message influence Justice Roberts’ opinion? What messages of “public import” did the picketers express? Did the Court go too far in protecting offensive speech in this case? What is a “public forum”? Why is it given “special protection” by the Court? How did the “time, place, and manner of the speech” as a peaceful demonstration on public property influence Justice Roberts’ opinion? What precedents did Justice Roberts cite in support of his opinion? Do you agree with Justice Alito’s dissent?

B. Compare the offensive speech in Snyder with that of Cohen, Matal and Texas v. Johnson? Are there important distinctions between them that would justify restriction of Phelps’ speech?

27. Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2011)

A. What interest did the state of California claim in banning violent video games for minors? How did Justice Scalia distinguish the precedent of Ginsberg v. New York (1968) from the California law? How did the Court’s holding in United States v. Stevens (2010) control Brown? Explain how Justice Scalia and Justice Breyer interpreted the scientific data quite differently. With whom do you agree? What is an “underinclusive” law? What is an “overinclusive” law? Is Scalia’s ruling an example of judicial activism or self-restraint? Can an important distinction be made between violent depictions in books, movies, and video games? Should government apply censorship differently to the different media?

B. How would a ban on violent video games for children compare to other content-based restrictions in Chaplinsky, Miller, and New York Times v. Sullivan? Are violent video games obscene under the Miller test? Do you think the Court should have carved out this exception to the First Amendment in the interest of protecting children? How might the precedent of Reno be relevant to Brown?

A. Why were The Slants denied a trademark registration by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office? What is the “disparagement” clause of the Lanham Act? What is “viewpoint discrimination”? What is wrong with banning speech that disparages racial and ethnic groups? How might this decision apply to offensive logos or trademarks of sports teams?

B. How do the cases of Matal v. Tam, Snyder v. Phelps, and Texas v. Johnson reflect the Court’s commitment to the principle of content and viewpoint neutrality?

Abrams, Floyd. The Soul of the First Amendment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Bollinger, Lee C., and Geoffrey R. Stone, eds. The Free Speech Century. New York: Oxford, 2019.

Farber, Daniel A. The First Amendment, 3rd ed. New York: Thomson Reuters/Foundation Press, 2010.

Shiell, Timothy C. Campus Hate Speech on Trial, 2nd ed. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.