Introduction

Walter Chaplinsky was a member of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religious group involved in several landmark First Amendment decisions, including the compulsory flag salute case of West Virginia v. Barnette (1943). On a “busy Saturday afternoon,” April 6, 1940, Chaplinsky was distributing religious literature on a public street while denouncing organized religion as a “racket.” A hostile crowd gathered. After police removed him for his own protection, an angry verbal exchange with authorities ensued. Chaplinsky said to a police officer, “You are a God damned racketeer” and “a damned Fascist and the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists.” Based on these remarks, Chaplinsky was convicted for violating a New Hampshire state law that punished the use of “offensive, derisive, or annoying” speech.

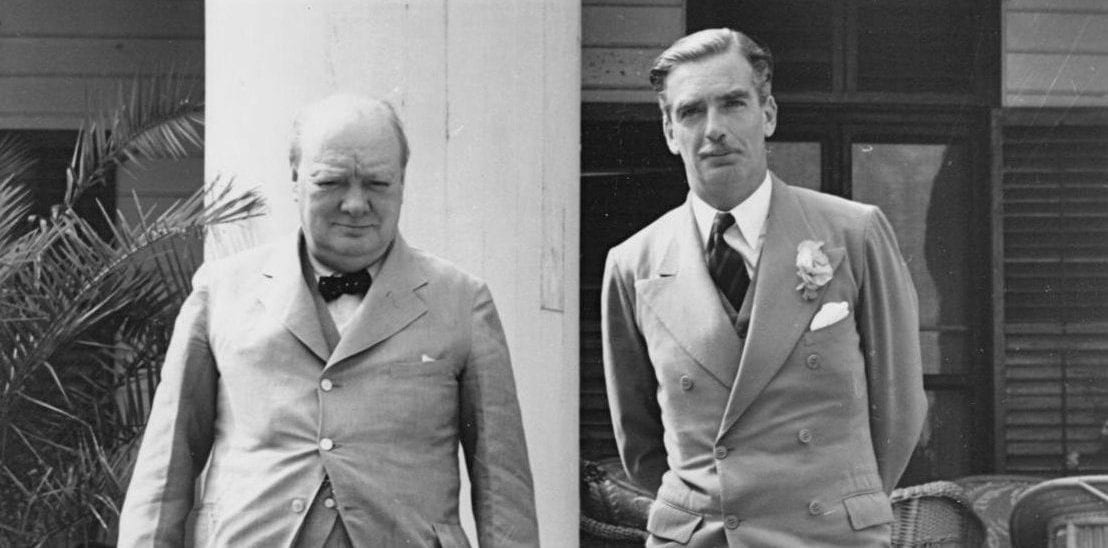

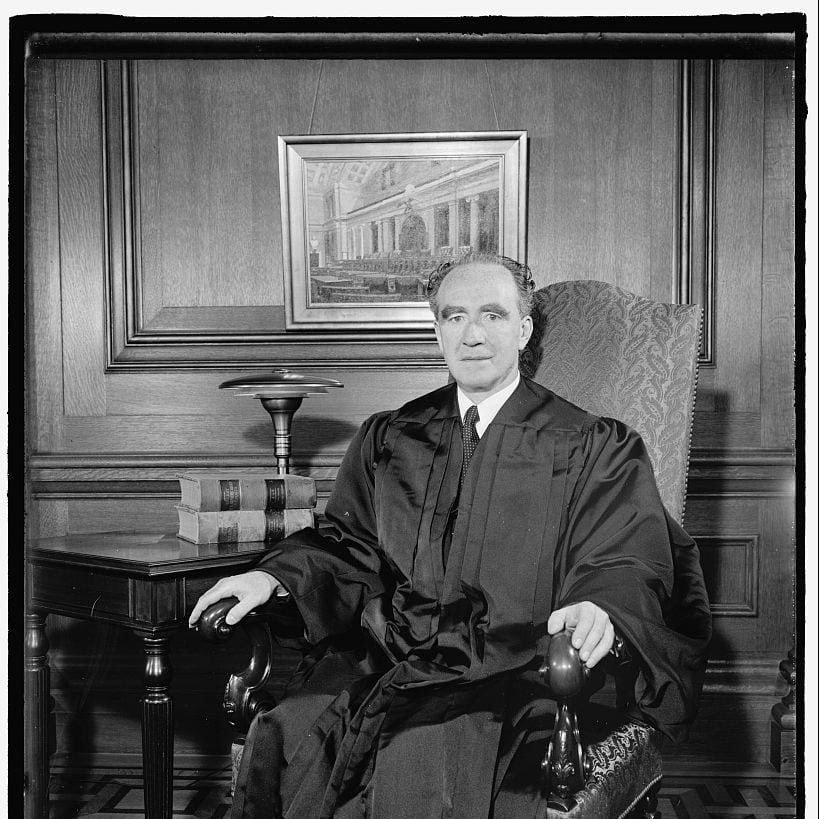

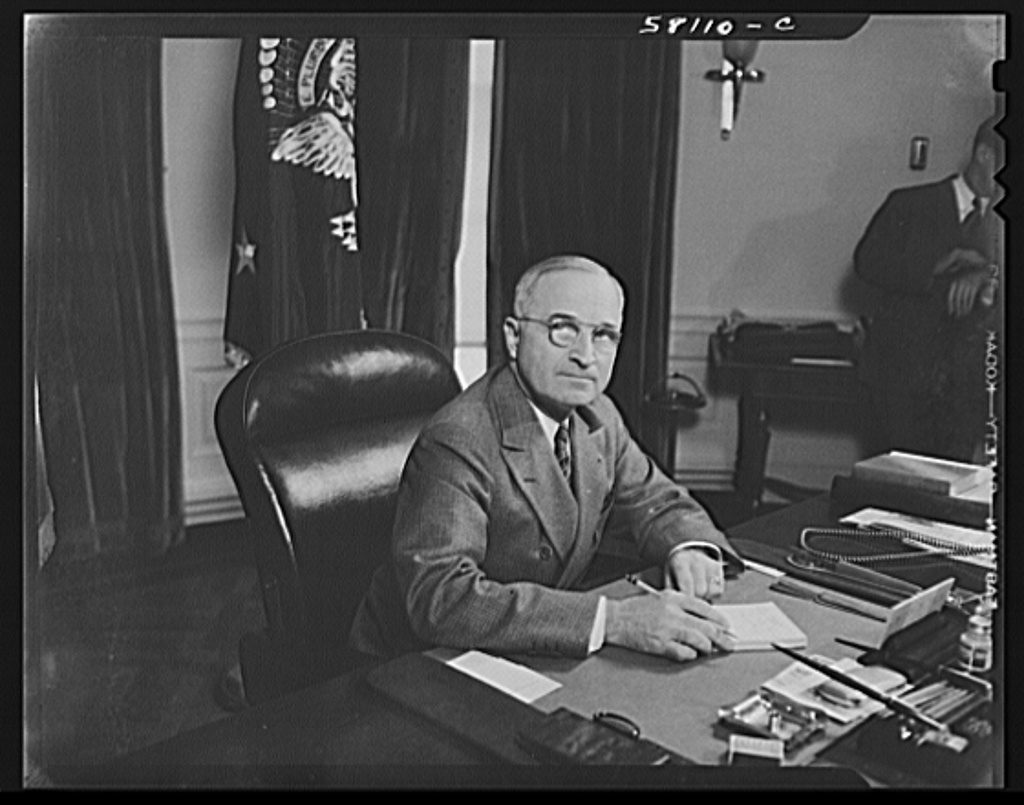

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Frank Murphy (1890–1949) upheld Chaplinsky’s conviction on the basis of the “fighting words” doctrine. According to Murphy, such words “by their very utterance, inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Moreover, they play no “essential part of any exposition of ideas” and are of such “slight social value” that they may be permissibly restricted in the greater interest of morality and public decency.

The fighting words doctrine is a rare content-based exception to Court’s general rule of content neutrality. Along with libel and obscenity, it constitutes a category of punishable speech outside the First Amendment. The fighting words doctrine also presumes a hierarchy of speech. At the top of this hierarchy, warranting the most protection, is speech that contributes to intellectual and political discourse. At the bottom, is low value speech like fighting words that play no “essential part of any exposition of ideas.” Such low value speech may be permissibly restricted in the interest of public order and morality.

While still on the books, the fighting words doctrine has been significantly narrowed through a series of cases that have reiterated protection for offensive, disturbing, and feared speech; see Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), Cohen v. California, Texas v. Johnson, Snyder v. Phelps, and Matal v. Tam. Some have sought to expand the fighting words doctrine to include hate speech as a new category of punishable expression. As it now stands, there is no separate content-based category of hate speech. Instead, hate speech is punishable depending upon its circumstances and context, as in the case of making a credible threat to someone (see Virginia v. Black).

Source: 315 U.S. 568, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/315/568.

- JUSTICE MURPHY delivered the opinion of the Court.

Appellant, a member of the sect known as Jehovah’s Witnesses, was convicted in the municipal court of Rochester, New Hampshire, for violation of Chapter 378, § 2, of the Public Laws of New Hampshire:

No person shall address any offensive, derisive, or annoying word to any other person who is lawfully in any street or other public place, nor call him by any offensive or derisive name, nor make any noise or exclamation in his presence and hearing with intent to deride, offend, or annoy him, or to prevent him from pursuing his lawful business or occupation.

The complaint charged that appellant,

with force and arms, in a certain public place in said city of Rochester, to-wit, on the public sidewalk on the easterly side of Wakefield Street, near unto the entrance of the City Hall, did unlawfully repeat the words following, addressed to the complainant, that is to say, “You are a God damned racketeer” and “a damned Fascist and the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists,” the same being offensive, derisive and annoying words and names.” . . .

. . . He was found guilty, and the judgment of conviction was affirmed by the Supreme Court of the state.

By motions and exceptions, appellant raised the questions that the statute was invalid under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States in that it placed an unreasonable restraint on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of worship, and because it was vague and indefinite. These contentions were overruled, and the case comes here on appeal.

There is no substantial dispute over the facts. Chaplinsky was distributing the literature of his sect on the streets of Rochester on a busy Saturday afternoon. Members of the local citizenry complained to the city marshal, Bowering, that Chaplinsky was denouncing all religion as a “racket.” Bowering told them that Chaplinsky was lawfully engaged, and then warned Chaplinsky that the crowd was getting restless. Some time later, a disturbance occurred and the traffic officer on duty at the busy intersection started with Chaplinsky for the police station but did not inform him that he was under arrest or that he was going to be arrested. On the way, they encountered Marshal Bowering, who had been advised that a riot was under way and was therefore hurrying to the scene. Bowering repeated his earlier warning to Chaplinsky, who then addressed to Bowering the words set forth in the complaint.

Chaplinsky’s version of the affair was slightly different. He testified that, when he met Bowering, he asked him to arrest the ones responsible for the disturbance. In reply, Bowering cursed him and told him to come along. Appellant admitted that he said the words charged in the complaint, with the exception of the name of the Deity.

Over appellant’s objection,[1] the trial court excluded, as immaterial, testimony relating to appellant’s mission “to preach the true facts of the Bible,” his treatment at the hands of the crowd, and the alleged neglect of duty on the part of the police. This action was approved by the court below, which held that neither provocation nor the truth of the utterance would constitute a defense to the charge.

It is now clear that “freedom of speech and freedom of the press, which are protected by the First Amendment from infringement by Congress, are among the fundamental personal rights and liberties which are protected by the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action” (Lovell v. City of Griffin).

Appellant assails the statute as a violation of all three freedoms—speech, press and worship—but only an attack on the basis of free speech is warranted. The spoken, not the written, word is involved. And we cannot conceive that cursing a public officer is the exercise of religion in any sense of the term. But even if the activities of the appellant which preceded the incident could be viewed as religious in character, and therefore entitled to the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment, they would not cloak him with immunity from the legal consequences for concomitant acts committed in violation of a valid criminal statute. We turn, therefore, to an examination of the statute itself.

Allowing the broadest scope to the language and purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is well understood that the right of free speech is not absolute at all times and under all circumstances. There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or “fighting” words—those which, by their very utterance, inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. It has been well observed that such utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.

“Resort to epithets or personal abuse is not in any proper sense communication of information or opinion safeguarded by the Constitution, and its punishment as a criminal act would raise no question under that instrument” (Cantwell v. Connecticut). . . .

On the authority of its earlier decisions, the state court declared that the statute’s purpose was to preserve the public peace, no words being “forbidden except such as have a direct tendency to cause acts of violence by the persons to whom, individually, the remark is addressed.” It was further said:

The word “offensive” is not to be defined in terms of what a particular addressee thinks. . . . The test is what men of common intelligence would understand would be words likely to cause an average addressee to fight. . . . The English language has a number of words and expressions which, by general consent, are “fighting words” when said without a disarming smile. . . . [S]uch words, as ordinary men know, are likely to cause a fight. So are threatening, profane, or obscene revilings. Derisive and annoying words can be taken as coming within the purview of the statute as heretofore interpreted only when they have this characteristic of plainly tending to excite the addressee to a breach of the peace. . . . The statute, as construed, does no more than prohibit the face-to-face words plainly likely to cause a breach of the peace by the addressee, words whose speaking constitutes a breach of the peace by the speaker—including “classical fighting words,” words in current useless “classical” but equally likely to cause violence, and other disorderly words, including profanity, obscenity, and threats.[2]

We are unable to say that the limited scope of the statute as thus construed contravenes the constitutional right of free expression. It is a statute narrowly drawn and limited to define and punish specific conduct lying within the domain of state power, the use in a public place of words likely to cause a breach of the peace (Cantwell v. Connecticut; Thornhill v. Alabama). This conclusion necessarily disposes of appellant’s contention that the statute is so vague and indefinite as to render a conviction thereunder a violation of due process. A statute punishing verbal acts, carefully drawn so as not unduly to impair liberty of expression, is not too vague for a criminal law (Fox v. Washington).

Nor can we say that the application of the statute to the facts disclosed by the record substantially or unreasonably impinges upon the privilege of free speech. Argument is unnecessary to demonstrate that the appellations “damned racketeer” and “damned Fascist” are epithets likely to provoke the average person to retaliation, and thereby cause a breach of the peace. . . .

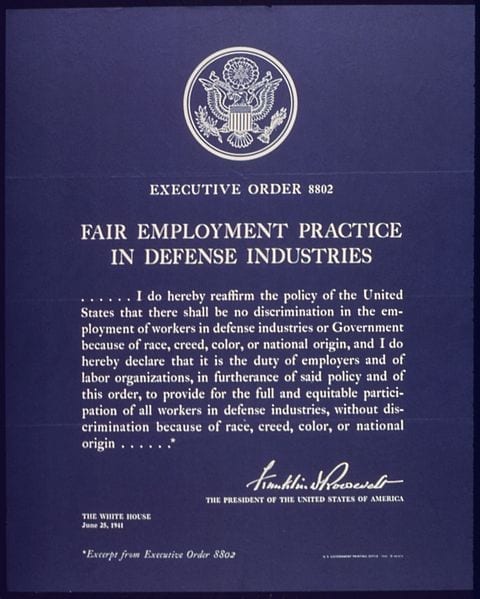

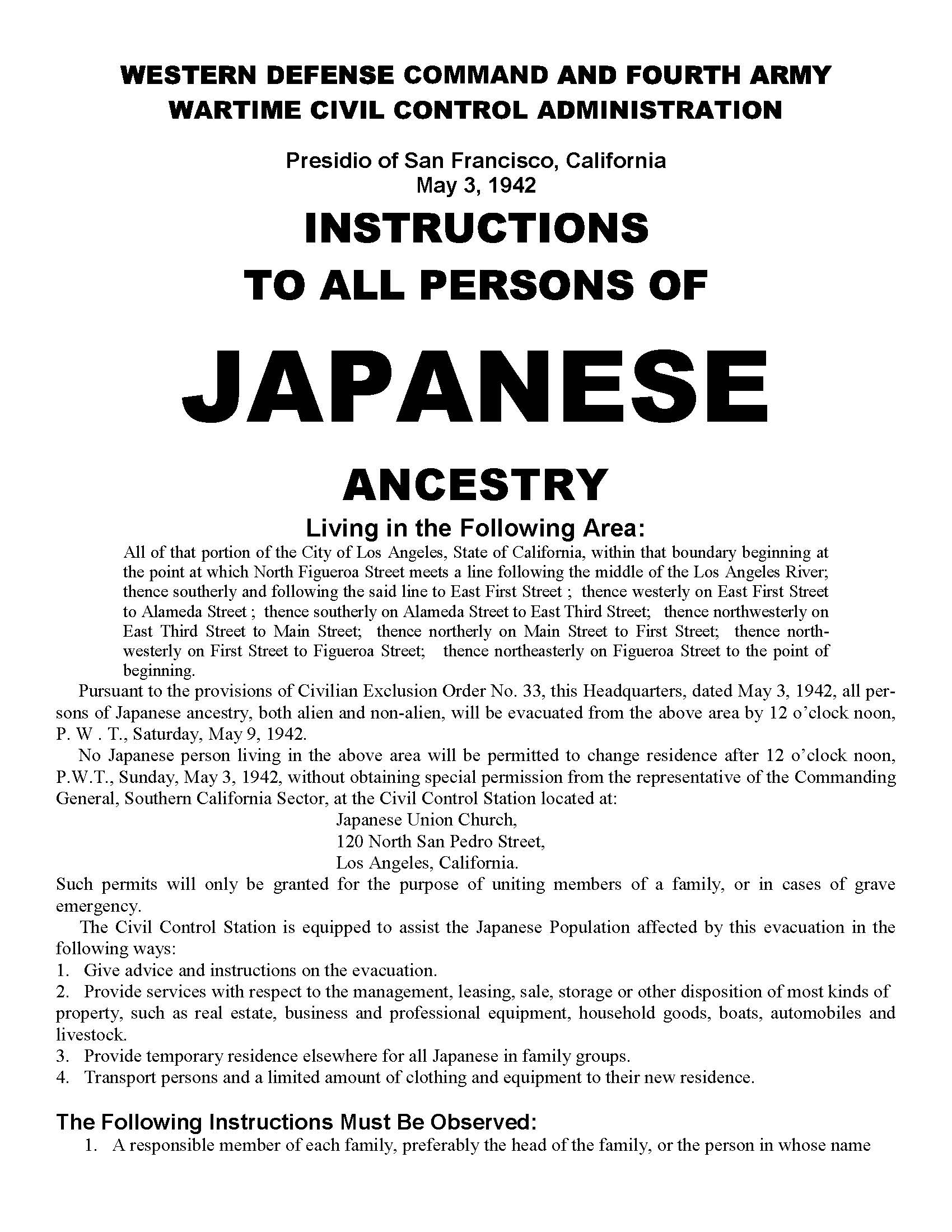

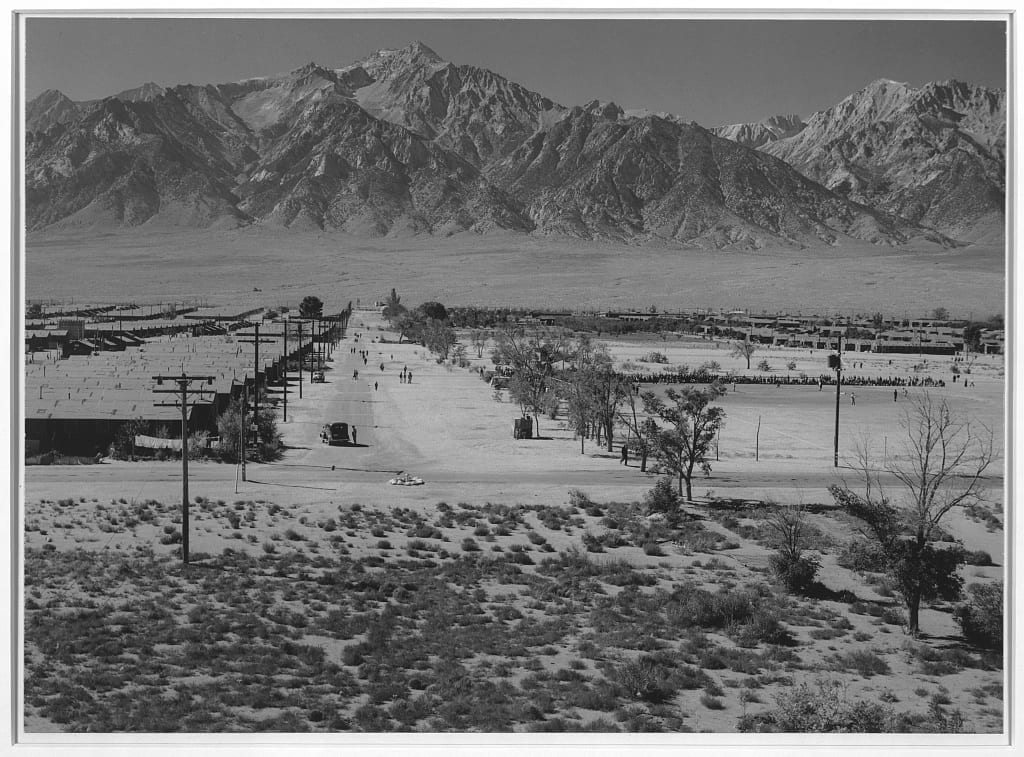

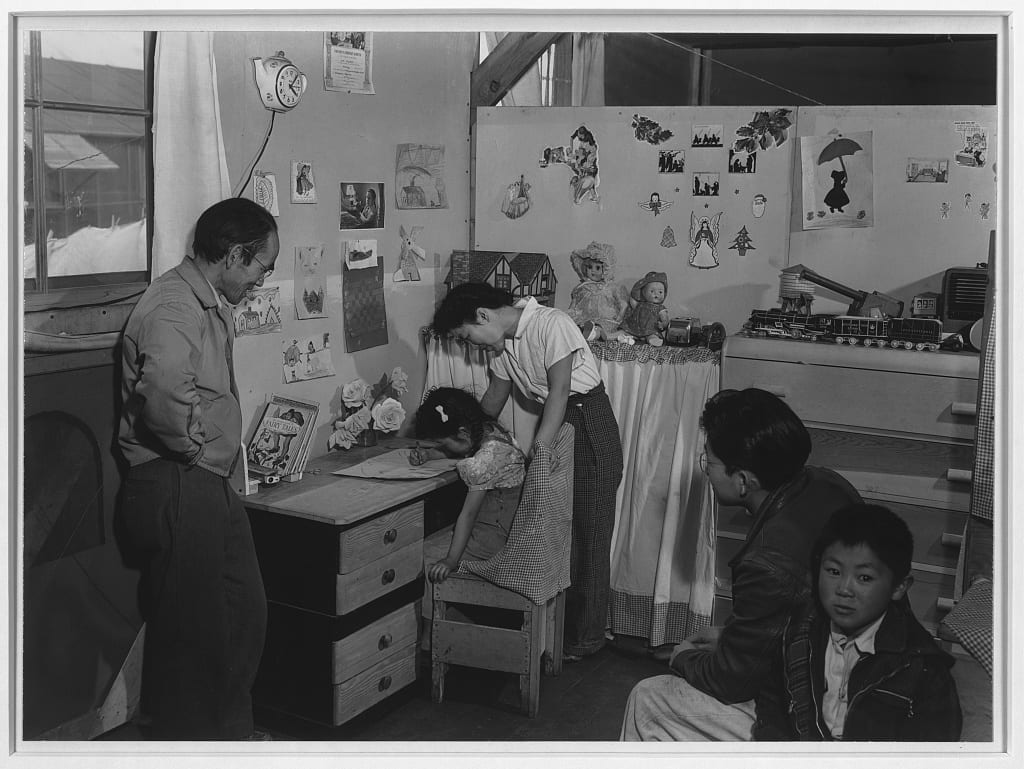

Japanese American Evacuation

April, 1942

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.