No related resources

Introduction

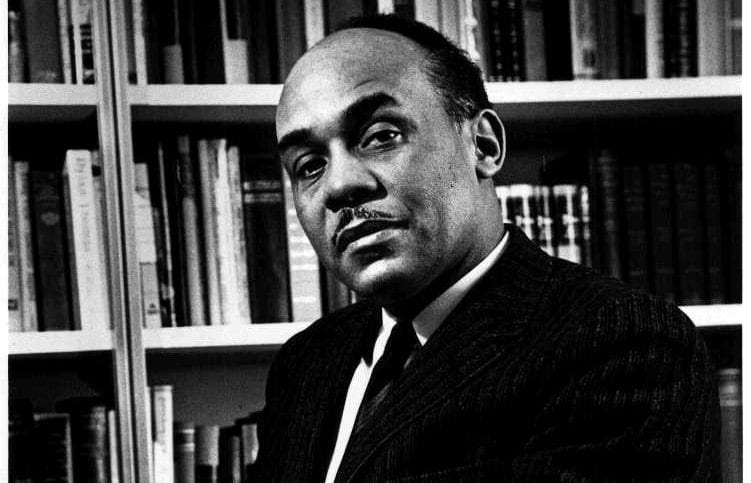

Bayard Rustin (1912–1987) was another important but lesser-known figure in the civil-rights cause, to which he made crucial contributions as a strategist, a tactician, an organizer, and an author.

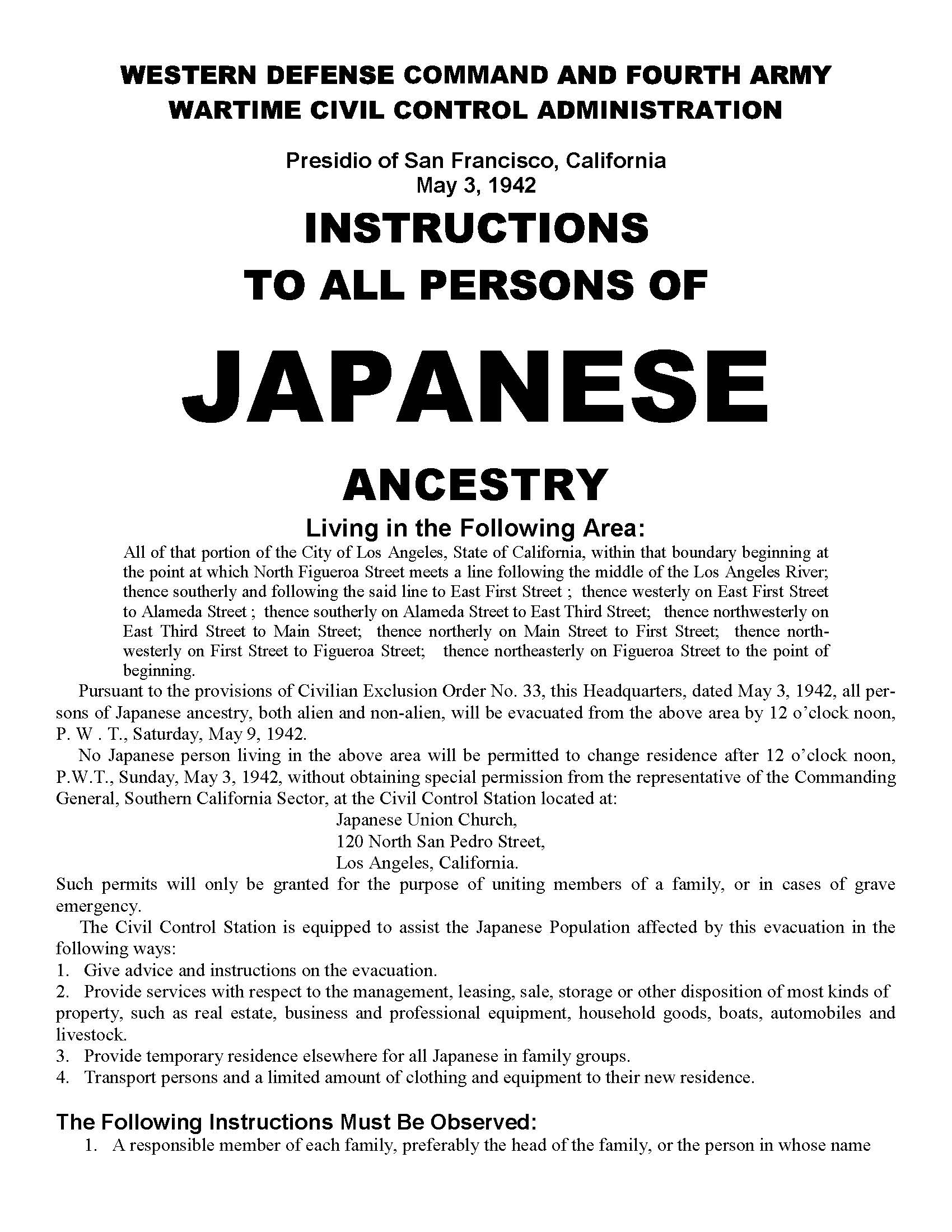

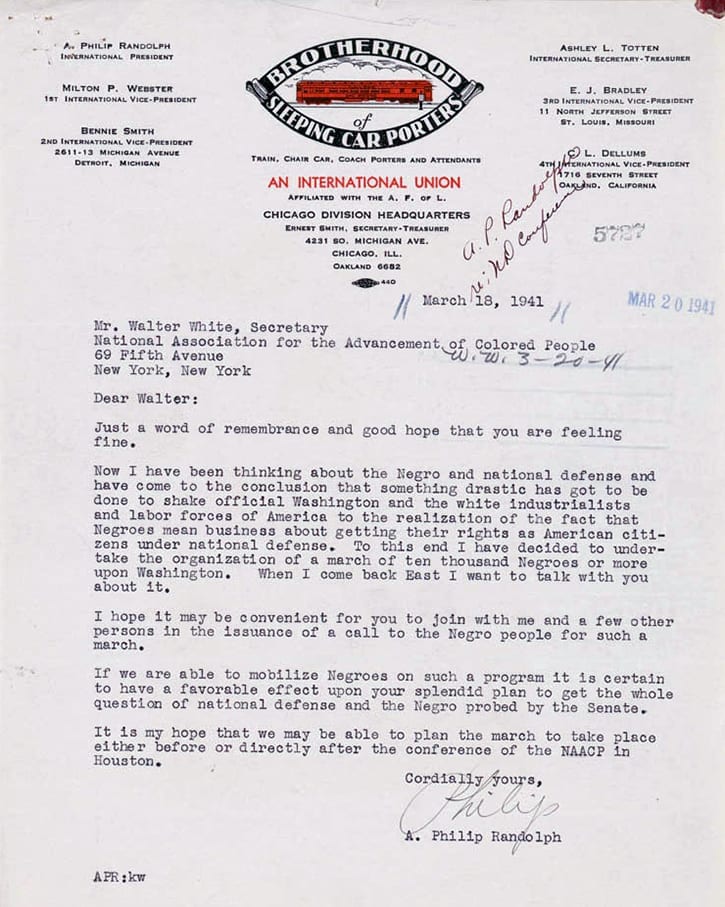

Rustin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and raised by his grandparents, including a grandmother who was a Quaker and a charter member of the NAACP. He studied briefly at Wilberforce University and in 1937 moved to New York City, where he furthered his education at City College of New York. In 1938 he joined the Youth Communist League but severed his ties with that organization within a few years. In 1941 he accepted Philip Randolph’s invitation to assist in planning the first March on Washington, and later that year he became youth secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), the nation’s most influential pacifist organization. A decade before the quickening of the civil rights movement in the 1950s, Rustin and FOR, in conjunction with FOR’s civil rights offshoot, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), organized a series of Freedom Rides to give effect to a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that invalidated state-mandated segregation on interstate buses. In 1956 he began a collaboration with Martin Luther King Jr. and contributed to the formation of King’s nonviolent direct-action method of civil rights protest. Rustin’s homosexuality made some civil rights leaders wary of according him a prominent role in the movement, but despite such concerns, he was the primary logistical organizer and one of the principal speakers at the 1963 March on Washington.

Rustin published two books of collected essays: Down the Line (1971) and Strategies for Freedom (1976). In the present selection, he recounts an early act of nonviolent resistance to the segregation regime.

Source: © 1942 Fellowship of Reconciliation, www.forusa.org. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. The Estate of Bayard Rustin.

Recently I was planning to go from Louisville to Nashville by bus. I bought my ticket, boarded the bus, and, instead of going to the back, I sat down in the second seat back. The driver saw me, got up, and came back to me.

“Hey you, you’re supposed to sit in the back seat.”

“Why?”

“Because that’s the law. N——s ride in back.”

I said, “My friend, I believe that this is an unjust law. If I were to sit in back I would be condoning injustice.”

Angry, but not knowing what to do, he got out and went into the station, but soon came out again, got into his seat, and started off.

This routine was gone through at each stop, but each time nothing came of it. Finally the driver, in desperation, must have phoned ahead, for about thirteen miles north of Nashville I heard sirens approaching. The bus came to an abrupt stop, and a police car and two motorcycles drew up beside us with a flourish. Four policemen got into the bus, consulted shortly with the driver, and came to my seat.

“Get up, you—N——!”

“Why?” I asked.

“Get up, you Black——!”

“I believe that I have a right to sit here,” I said quietly. “If I sit in the back of the bus I am depriving that child”—I pointed to a little white child of five or six—“of the knowledge that there is injustice here, which I believe it is his

right to know. It is my sincere conviction that the power of love in the world is the greatest power existing. If you have a greater power, my friend, you may move me.”

How much they understood of what I was trying to tell them I do not know. By this time they were impatient and angry. As I would not move they began to beat me about the head and shoulders, and I shortly found myself

knocked to the floor. Then they dragged me out of the bus and continued to kick and beat me.

Knowing that if I tried to get up or protect myself in the first heat of their anger they would construe it as an attempt to resist and beat me down again, I forced myself to be still and wait for their kicks, one after another. Then I stood up, spreading out my arms parallel to the ground, and said, “There is no need to beat me. I am not resisting you.”

At this three white men, obviously Southerners by their speech, got out of the bus and remonstrated with the police. Indeed, as one of the policemen raised his club to strike me, one of them, a little fellow, caught hold of it and said, “Don’t you do that!” A second policeman raised his club to strike the little man, and I stepped between them, facing the man, and said, “Thank you, but there is no need to do that. I do not wish to fight. I am protected well.”

An elderly gentleman, well-dressed and also a Southerner, asked the police where they were taking me.

They said, “Nashville.”

“Don’t worry, son,” he said to me. “I’ll be there to see that you get justice.”

I was put into the back seat of the police car, between two policemen. Two others sat in front. During the thirteen-mile ride to town they called me every conceivable bad name and said anything they could think of to incite me to violence. I found that I was shaking with nervous strain, and to give myself something to do, I took out a piece of paper and a pencil and began to write from memory a chapter from one of Paul’s letters.

When I had written a few sentences the man on my right said, “What’re you writing?” and snatched the paper from my hand. He read it, then crumpled it into a ball and pushed it in my face. The man on the other side gave me a kick.

A moment later I happened to catch the eye of the young policeman in the front seat. He looked away quickly, and I took a renewed courage from the realization that he could not meet my eyes because he was aware of the injustice being done. I began to write again, and after a moment I leaned forward and touched him on the shoulder. “My friend,” I said, “how do you spell ‘difference’?”

He spelled it for me—incorrectly—and I wrote it correctly and went on.

When we reached Nashville a number of policemen were lined up on both sides of the hallway down which I had to pass on my way to the captain’s office. They tossed me from one to another like a volleyball. By the time I reached the office the lining of my best coat was torn, and I was considerably rumpled. I straightened myself as best I could and went in. They had my bag, and went through it and my papers, finding much of interest, especially in the Christian Century and Fellowship.

Finally the captain said, “Come here, N——.”

I walked directly to him. “What can I do for you?” I asked.

“N——,” he said menacingly, “you’re supposed to be scared when you come in here!”

“I am fortified by truth, justice, and Christ,” I said. “There is no need for me to fear.”

He was flabbergasted and, for a time, completely at a loss for words. Finally he said to another officer, “I believe the N——’s crazy!”

They sent me into another room and went into consultation. The wait was long, but after an hour and a half they came for me and I was taken for another ride, across town. At the courthouse, I was taken down the hall to the office of the assistant district attorney, Mr. Ben West. As I got to the door I heard a voice, “Say, you colored fellow, hey!” I looked around and saw the elderly gentleman who had been on the bus.

“I’m here to see that you get justice,” he said.

The assistant district attorney questioned me about my life, the Christian Century, the F.O.R., pacifism, and the war for half an hour. Then he asked the police to tell their side of what had happened. They did, stretching the truth a good deal in spots and including several lies for seasoning. Mr. West then asked me to tell my side.

“Gladly,” I said, “and I want you,” turning to the young policeman who had sat in the front seat, “to follow what I say, and stop me if I deviate from the truth in the least.”

Holding his eyes with mine, I told the story exactly as it had happened, stopping often to say, “Is that right?” or “Isn’t that what happened?” to the young policeman. During the whole time he never once interrupted me, and when I was through I said, “Did I tell the truth just as it happened?” and he said,

“Well . . .”

Then Mr. West dismissed me, and I was sent to wait alone in a dark room. After an hour, Mr. West came in and said, very kindly, “You may go, Mister Rustin.”

I left the courthouse, believing all the more strongly in the nonviolent approach, for I am certain that I was addressed as “Mister,” as no Negro is ever addressed in the South; that I was assisted by those three men; and that the elderly gentleman interested himself in my predicament because I had, without fear, faced the four policemen and said, "There is no need to beat me. I offer you no resistance.”

First News of the Final Solution

August 10, 1942

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.