No related resources

Introduction

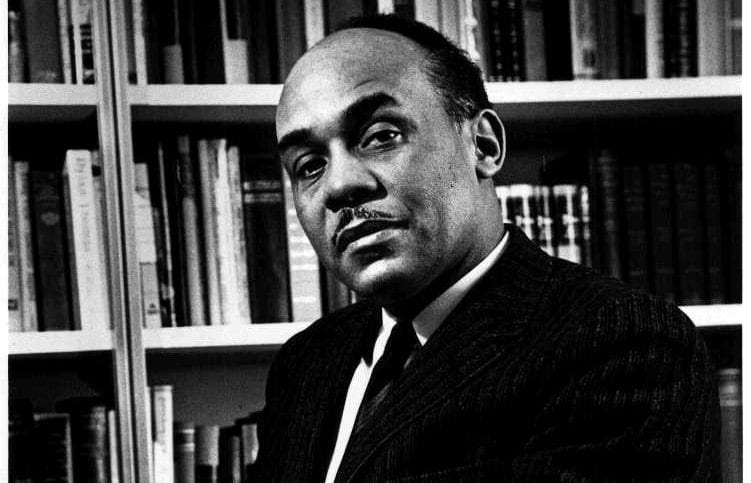

The March on Washington will forever be associated in the public mind with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered at that 1963 event the most famous speech by any twentieth-century American. But the march was not the brainchild of King. The 1963 march reprised an effort initiated a generation earlier by A. Philip Randolph (1889–1979).

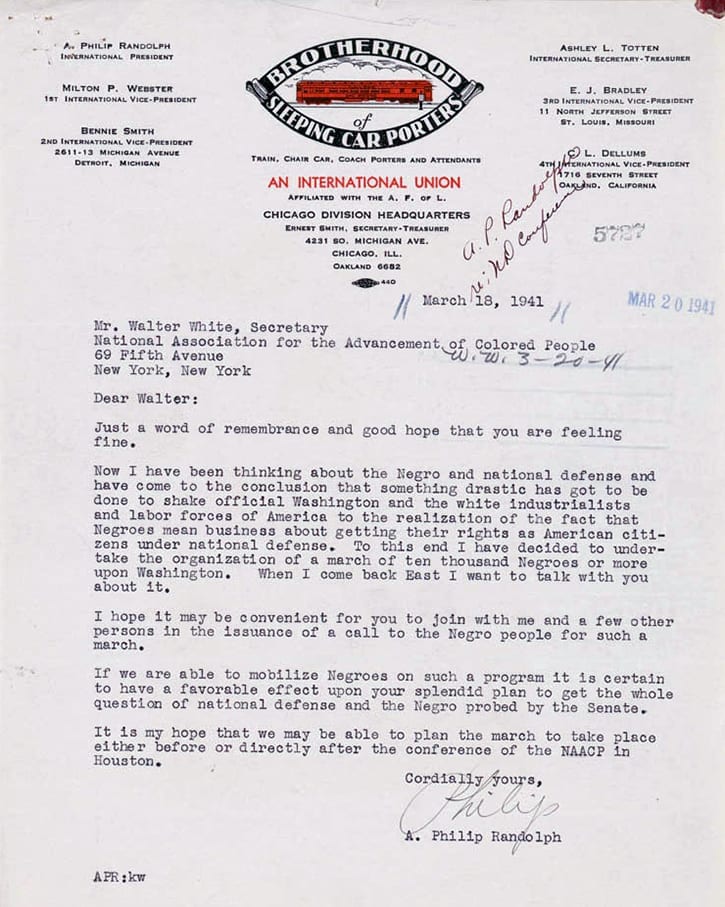

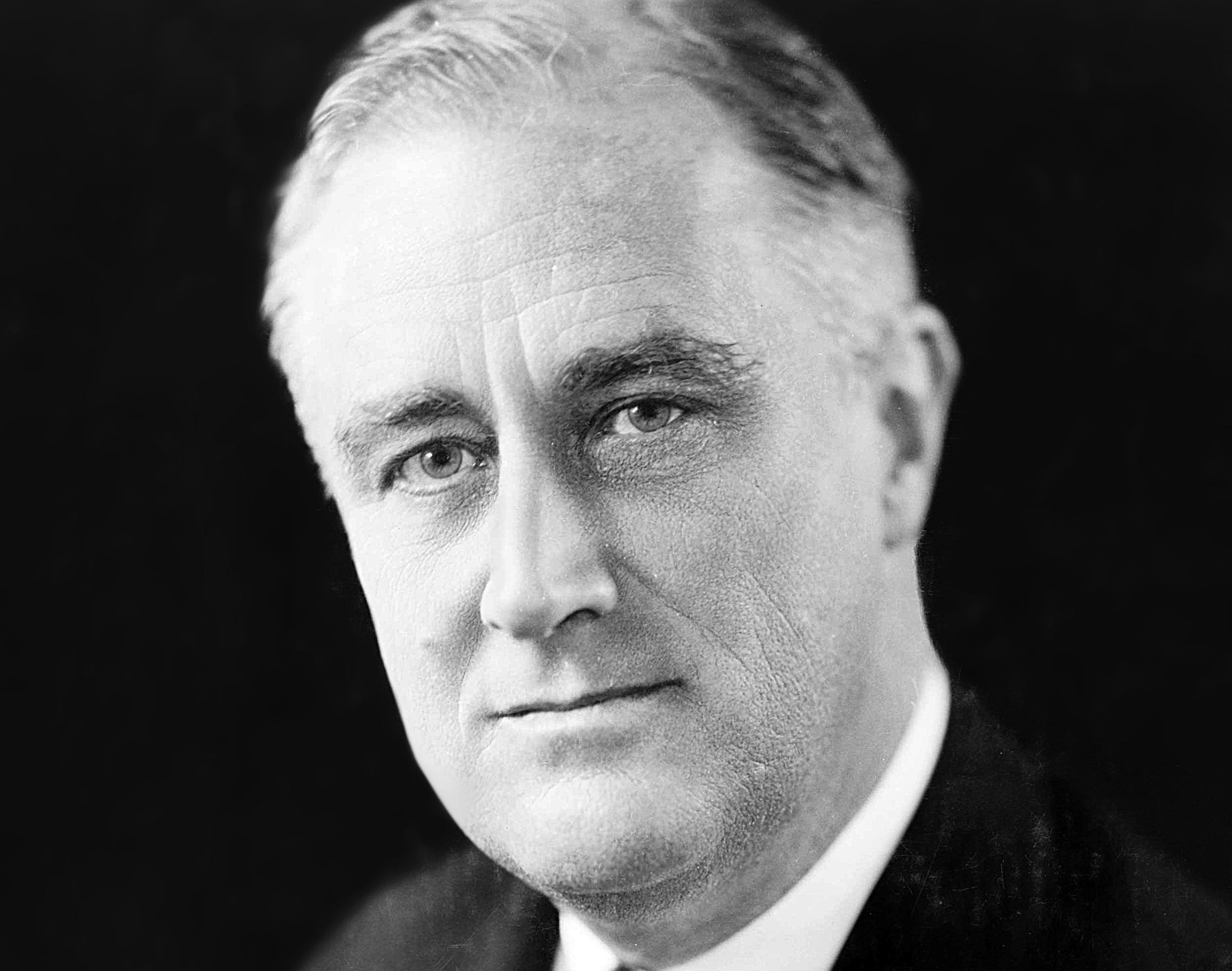

Randolph was born in Crescent City, Florida, and grew up in nearby Jacksonville, where he attended the Cookman Institute, a school of higher learning for African Americans. After college he moved to New York City and studied English literature and sociology at City College. He spent a few years working in various jobs, including performing in local productions as a Shakespearean actor, and became active in the cause of organizing black laborers. He and a law student acquaintance co-founded an employment agency, then a political magazine. He ran unsuccessfully for state office in the early 1920s, but then became founder and president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the nation’s first African American labor union. From this position Randolph emerged as an influential labor and civil rights activist, successfully lobbying both the Roosevelt and Truman administrations for employment and antisegregation reforms. He went on to serve among the primary organizers of the 1963 March on Washington, where he was one of the event’s principal speakers. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson awarded Randolph the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

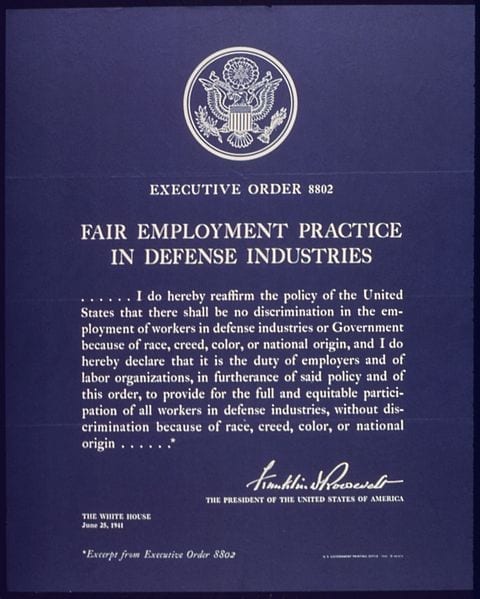

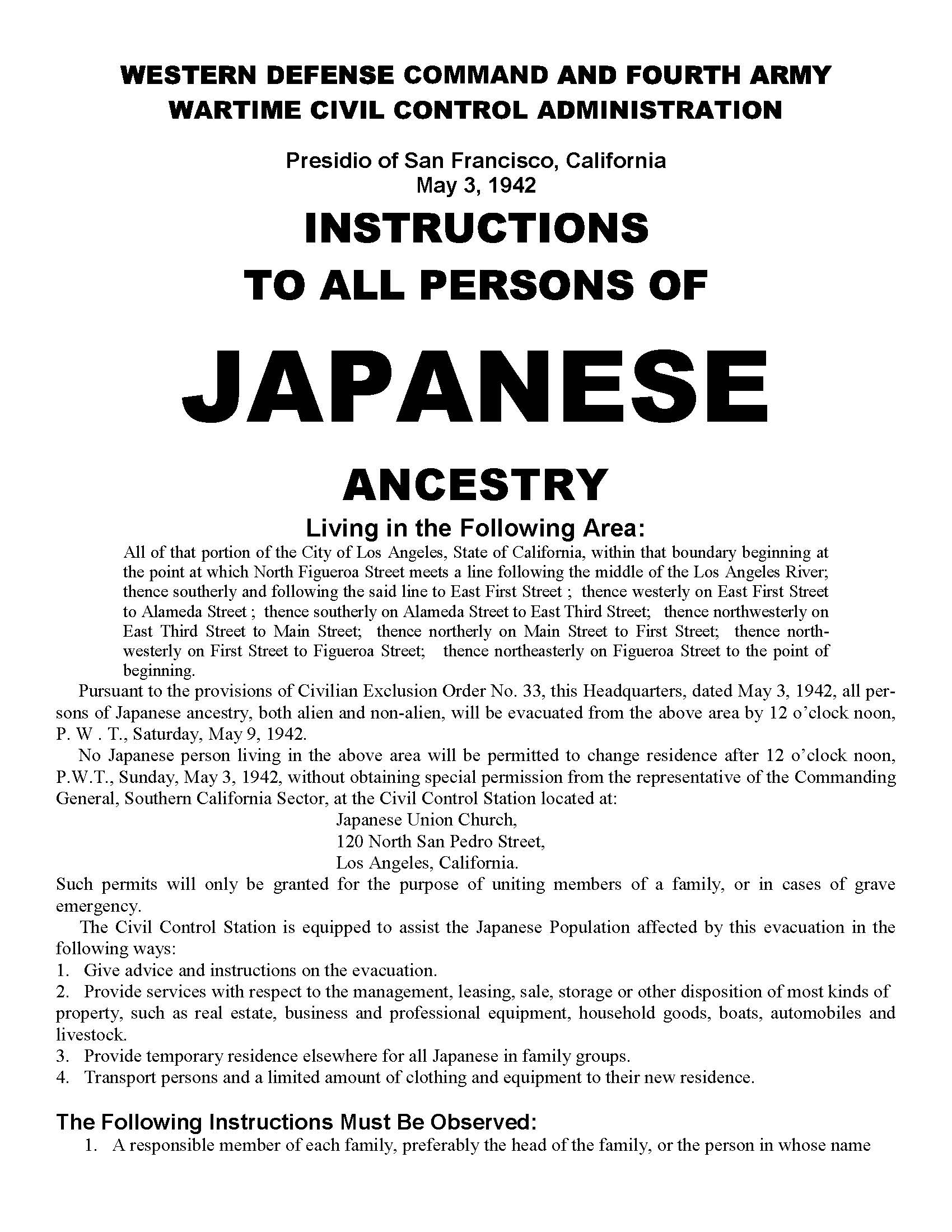

Randolph had initially planned a mass march on Washington for summer 1941 to protest employment discrimination. That march was called off after President Roosevelt agreed to issue Executive Order 8802, which prohibited racial discrimination by federal defense contractors and also established the Fair Employment Practices Commission. In the present selection, Randolph explains the rationale for the direct-action protest he had planned in 1941.

Source: A. Philip Randolph, “Why Should We March?” Survey Graphic 31 (November 1942), 488–89; available at https://goo.gl/ch5w2Q

Though I have found no Negroes who want to see the United Nations1 lose this war, I have found many who, before the war ends, want to see the stuffing knocked out of white supremacy and of empire over subject peoples. American Negroes, involved as we are in the general issues of the conflict, are confronted not with a choice but with the challenge both to win democracy for ourselves at home and to help win the war for democracy the world over.

. . . There is no escape from the horns of this dilemma. There ought not to be escape. For if the war for democracy is not won abroad, the fight for democracy cannot be won at home. If this war cannot be won for the white peoples, it will not be won for the darker races.

Conversely, if freedom and equality are not vouchsafed the peoples of color, the war for democracy will not be won. Unless this double-barreled thesis is accepted and applied, the darker races will never wholeheartedly fight for the victory of the United Nations. That is why those familiar with the thinking of the American Negro have sensed his lack of enthusiasm, whether among the educated or uneducated, rich or poor, professional or non-professional, religious or secular, rural or urban, north, south, east, or west.

That is why questions are being raised by Negroes in church, labor union, and fraternal society; in poolroom, barbershop, schoolroom, hospital, hair-dressing parlor; on college campus, railroad, and bus. One can hear such questions asked as these: What have Negroes to fight for? What’s the difference between Hitler and the “cracker” Talmadge of Georgia?2 Why has a man got to be Jim Crowed3 to die for democracy? If you haven’t got democracy yourself, how can you carry it to somebody else?

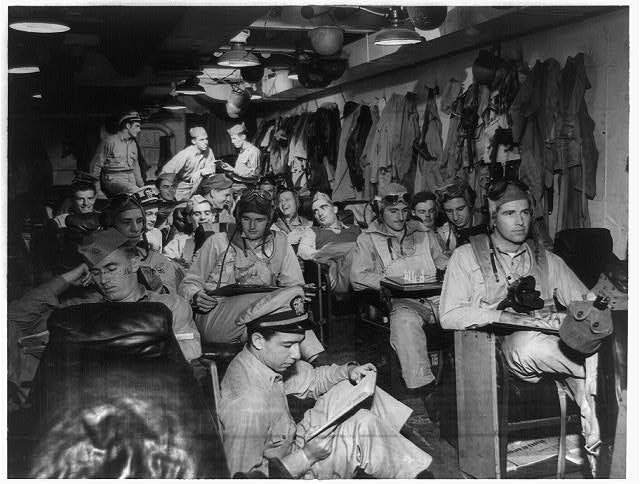

What are the reasons for this state of mind? The answer is: discrimination, segregation, Jim Crow. Witness the Navy, the Army, the Air Corps; and also government services at Washington. In many parts of the South, Negroes in Uncle Sam’s uniform are being put upon, mobbed, sometimes even shot down by civilian and military people, and on occasion lynched. Vested political interests in race prejudice are so deeply entrenched that to them winning the war against Hitler is secondary to preventing Negroes from winning democracy for themselves. This is worth many divisions to Hitler and Hirohito.4 While labor, business, and farm are subjected to ceilings and floors5 and not allowed to carry on as usual, these interests trade in the dangerous business of race and hate as usual.

When the defense program began and billions of taxpayers’ money were appropriated for guns, ships, tanks, and bombs, Negroes presented themselves for work only to be given the cold shoulder. North as well as South, and despite qualifications, Negroes were denied skilled employment. Not until their wrath and indignation took the form of a proposed protest march on Washington, scheduled for July 1, 1941, did things begin to move in the form of defense jobs for Negroes. The march was postponed by the timely issuance (June 25, 1941) of the famous Executive Order No. 88026 by President Roosevelt. But this order and the President’s Committee on Fair Employment Practice, established thereunder, have as yet only scratched the surface by way of eliminating discriminations on account of race or color in war industry. Both management and labor unions in too many places and too many ways are still drawing the color line.

It is to meet this situation squarely with direct action that the March on Washington Movement launched its present program of protest mass meetings. Twenty thousand were in attendance at Madison Square Garden, June 16; sixteen thousand in the Coliseum in Chicago, June 26; nine thousand in the City Auditorium of St. Louis, August 14. Meetings of such magnitude were unprecedented among Negroes. The vast throngs were drawn from all walks and levels of Negro life—businessmen, teachers, laundry workers, Pullman porters, waiters, and red caps;7 preachers, crapshooters, and social workers; jitterbugs and PhD’s. They came and sat in silence, thinking, applauding only when they considered the truth was told, when they felt strongly that something was going to be done about it.

The March on Washington Movement is essentially a movement of the people. It is all Negro and pro-Negro, but not for that reason anti-white or anti-Semitic, or anti-Catholic, or anti-foreign, or anti-labor. Its major weapon is the nonviolent demonstration of Negro mass power. Negro leadership has united back of its drive for jobs and justice. “Whether Negroes should focus on Washington, and if so, when?” will be the focus of a forthcoming national conference. For the plan of a protest march has not been abandoned. Its purpose would be to demonstrate that American Negroes are in deadly earnest, and all out for their full rights. No power on earth can cause them today to abandon their fight to wipe out every vestige of second-class citizenship and the dual standards that plague them.

A community is democratic only when the humblest and weakest per- son can enjoy the highest civil, economic, and social rights that the biggest and most powerful possess. To trample on these rights of both Negroes and poor whites is such a commonplace in the South that it takes readily to anti-social, anti-labor, anti-Semitic, and anti-Catholic propaganda. It was because of laxness in enforcing the Weimar constitution8 in republican Germany that Nazism made headway. Oppression of the Negroes in the United States, like suppression of the Jews in Germany, may open the way for fascist dictatorship.

By fighting for their rights now, American Negroes are helping to make America a moral and spiritual arsenal for democracy. Their fight against the poll tax, against lynch law, segregation, and Jim Crow, their fight for economic, political, and social equality, thus becomes part of the global war for freedom.

PROGRAM OF THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON MOVEMENT

- We demand, in the interest of national unity, the abrogation of every law which makes a distinction in treatment between citizens based on religion, creed, color, or national origin. This means an end to Jim Crow in education, in housing, in transportation, and in every other social, economic, and political privilege; and especially, we demand, in the capital of the nation, an end to all segregation in public places and in public institutions

- We demand legislation to enforce the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments guaranteeing that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, so that the full

weight of the national government may be used for the protection of life and thereby may end the disgrace of lynching.

- We demand the enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and the enactment of the Pepper Poll Tax bill9 so that all barriers in the exercise of the suffrage are eliminated.

- We demand the abolition of segregation and discrimination in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Corps, and all other branches of national defense.

- We demand an end to discrimination in jobs and job training. Further, we demand that the FEPC [Fair Employment Practices Committee] be made a permanent administrative agency of the U.S.

government and that it be given power to enforce its decisions based on its findings.

- We demand that federal funds be withheld from any agency which practices discrimination in the use of such funds.

- We demand colored and minority group representation on all administrative agencies so that these groups may have recognition of their democratic right to participate in formulating policies.

- We demand representation for the colored and minority racial groups on all missions, political and technical, which will be sent to the peace conference so that the interests of all people everywhere

may be fully recognized and justly provided for in the postwar settlement.

- 1. The term “United Nations” was first used in a joint statement issued January 1, 1942, by the United States, Great Britain, the USSR, and twenty-three other nations, pledging to continue fighting the Axis powers.

- 2. Eugene Talmadge (1884–1946), a supporter of racial segregation, served three terms as governor of Georgia.

- 3. “Jim Crow” was the name given to the system of state laws that imposed segregation in the South after Reconstruction. “Jim Crow” was originally a character in minstrel shows who caricatured African Americans.

- 4. Hirohito (1901–1989) was emperor of Japan from 1926 until his death.

- 5. “Ceilings and floors” refers to the various sorts of wage and price controls imposed on business and commerce during the New Deal and, later, World War II.

- 6. Executive Order 8802, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941, prohibited racial or ethnic discrimination in U.S. governmental defense agencies and by private defense contractors. It established a federal agency, the Fair Employment Practices Commission, to enforce the order.

- 7. The red cap was worn by railroad station porters to distinguish them from employees who performed other duties on trains.

- 8. The Weimar Constitution, enacted into law in 1919, ostensibly established parliamentary democracy in post–World War I Germany, but amid economic depression and political division, it failed to bring stability and was dissolved in 1933 when Adolph Hitler rose to power.

- 9. Senator Claude Pepper (D-FL) (1900–1989) regularly introduced a bill to abolish poll taxes as prerequisites to voting. The bill was never enacted into law.

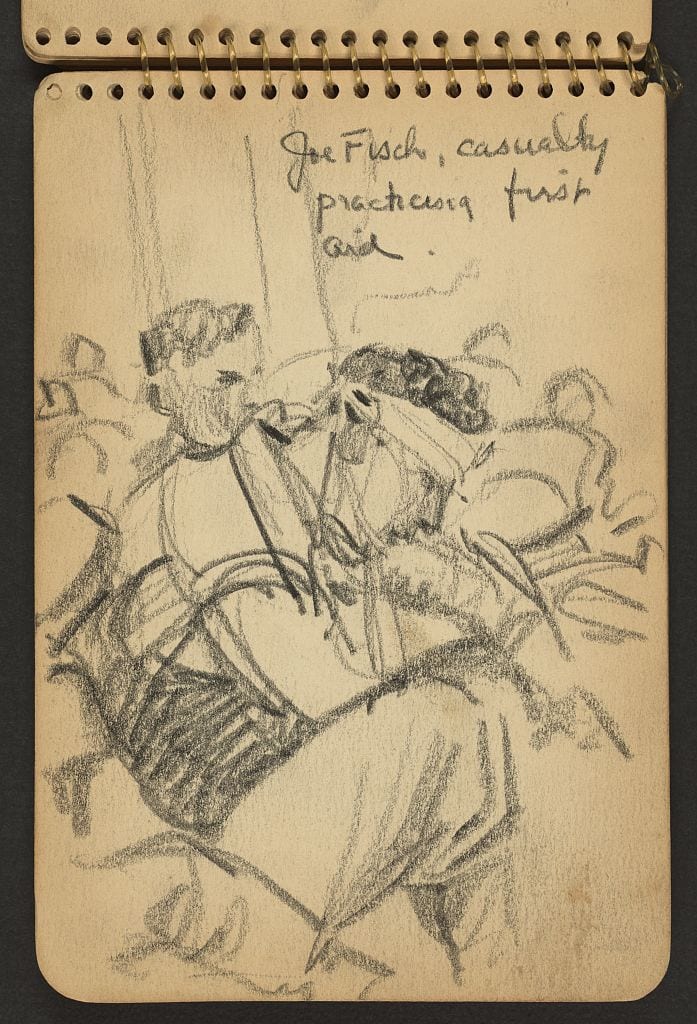

Pacific War Diary

December 31, 1945

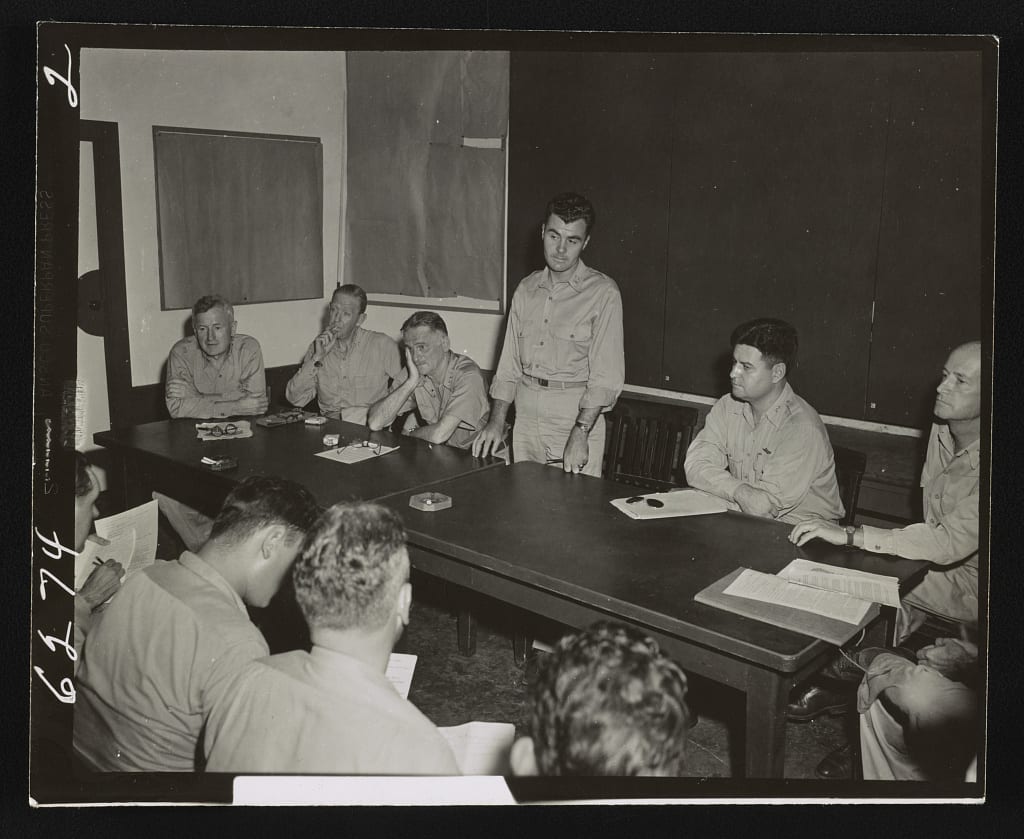

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.