Introduction

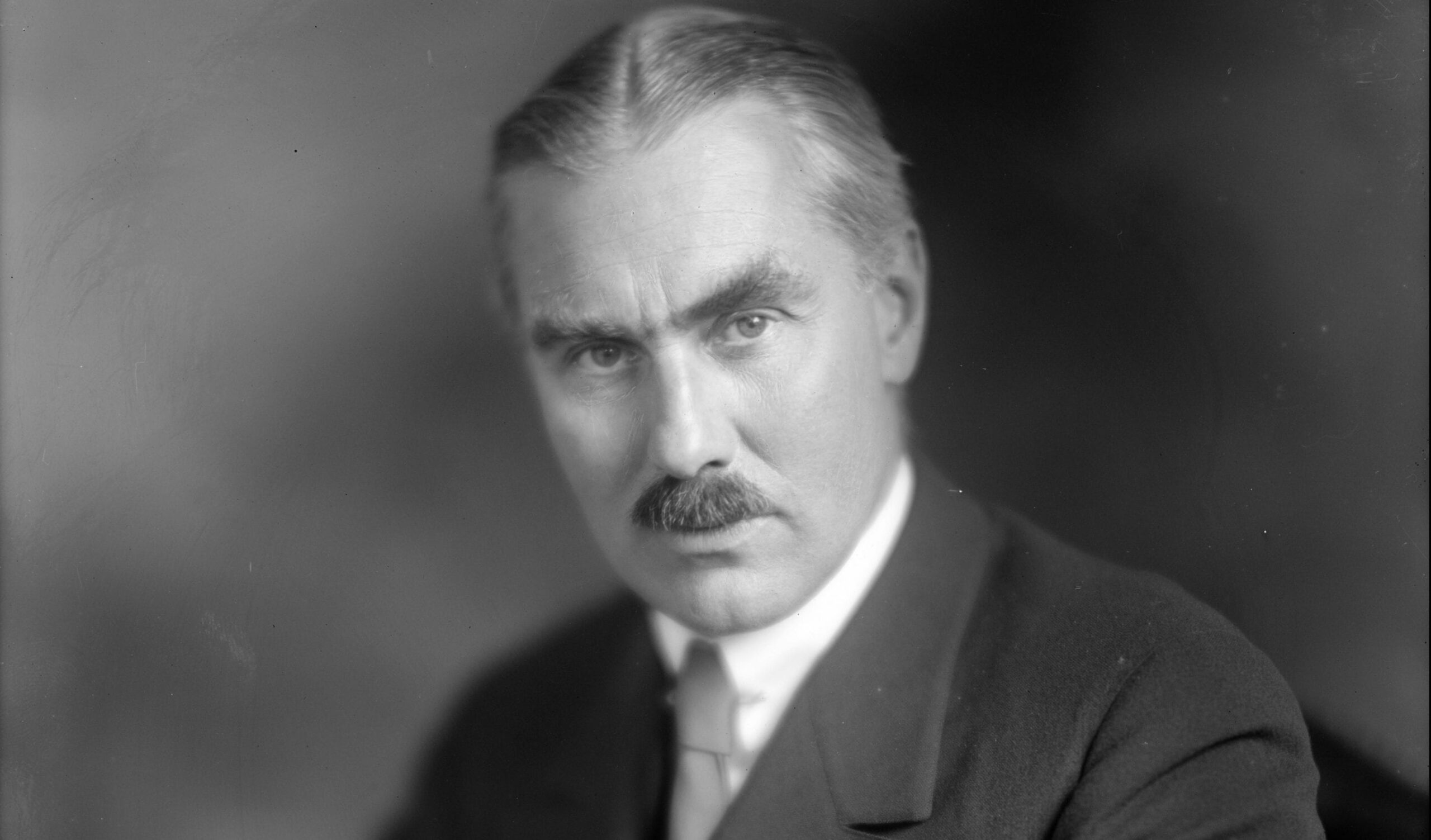

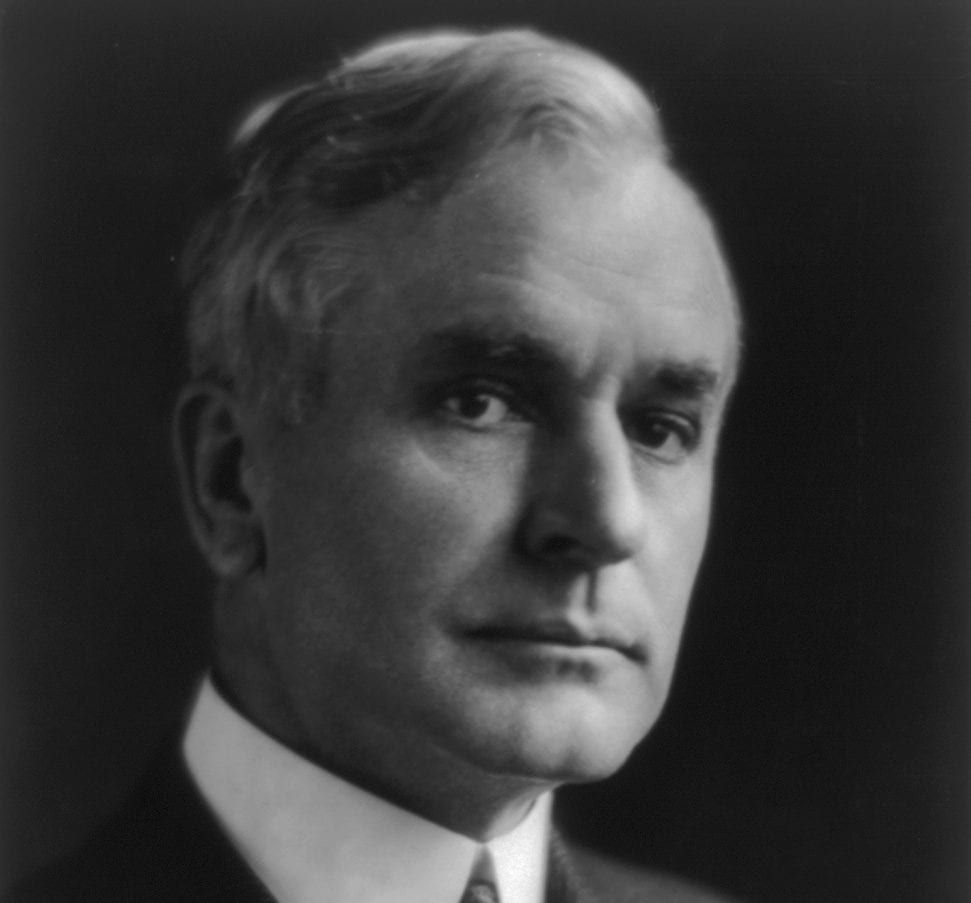

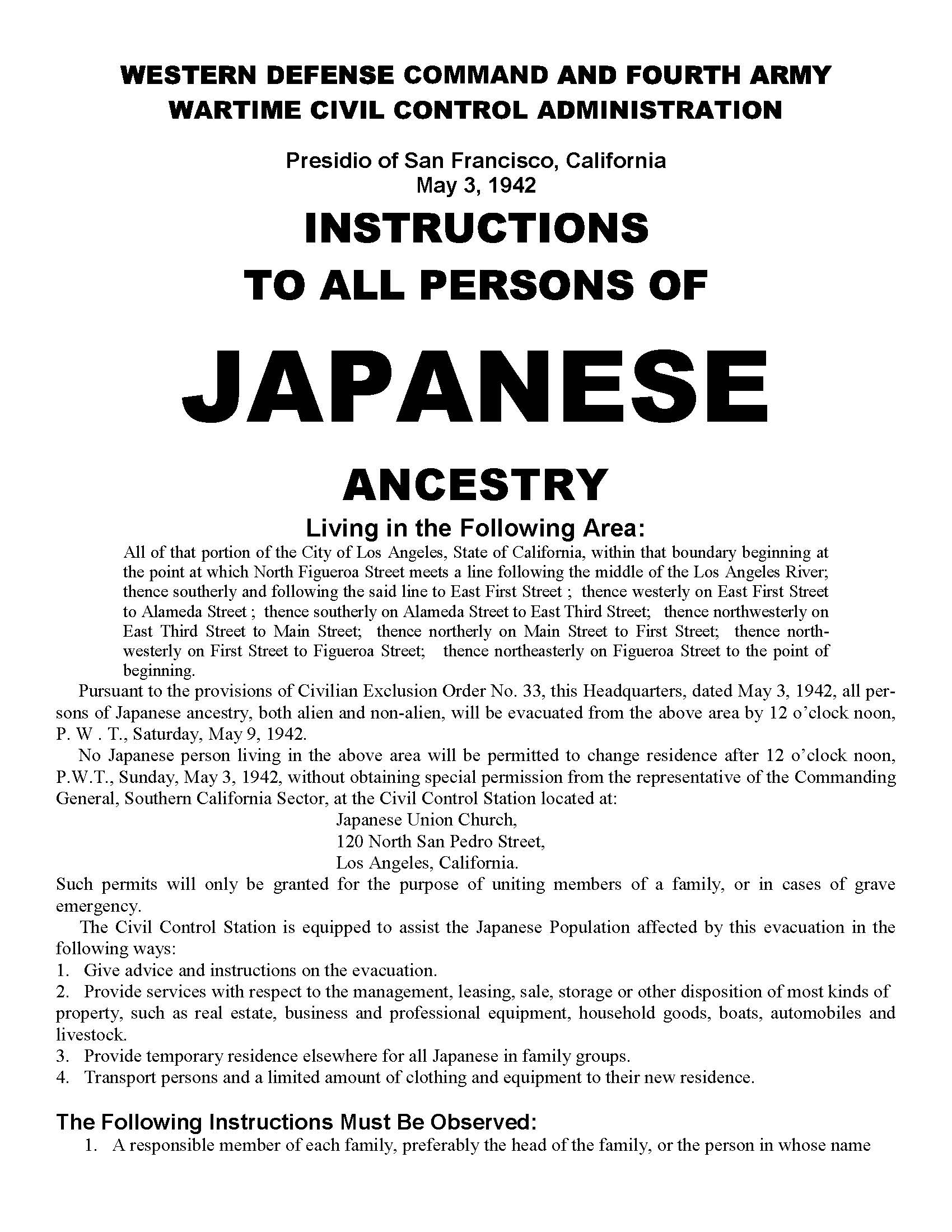

Senator Bennett Champ Clark (1890–1954, D-MO), who served in the U.S. Senate from 1933 to 1945, was a strong proponent of making neutrality a cornerstone of American foreign policy. He made his case directly to the public in this December 1935 Harper’s Monthly article, “Detour Around War: A Proposal for a New American Policy.” Clark served on the Senate’s Munitions Investigation Committee, popularly known as the Nye Committee for its chairman, Senator Gerald P. Nye (R-ND). In the mid-1930s the Nye Committee held a series of investigations into “Merchants of Death” conspiracy theories but uncovered little hard evidence. Nonetheless, the belief persisted that munitions manufacturers and financiers had secretly maneuvered the United States into WWI to continue their profitable war trade and to secure repayment of war loans to the Allies. In this opinion piece, Clark urges a renewal and expansion of the 1935 Neutrality Act. Congress heeded his call by renewing the act and adding a prohibition on loans to warring nations in the Neutrality Law of 1936. In 1937, Congress mandated that nations at war could purchase from the US only goods that were not war-related and must transport them in their own ships, a policy known as “cash and carry.”

Source: Bennett Champ Clark, “Detour Around War: A Proposal for a New American Policy,” Harper’s Monthly, December 1935, 1–9. Originally published as “Detour Around War: A Proposal for a New American Policy,” December 1935, Harper’s Monthly, 1-9, © 1935 by Harper’s Monthly. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

. . . At the present the desire to keep the United States from becoming involved in any war between foreign nations seems practically unanimous among the rank and file of American citizens; but it must be remembered there was an almost equally strong demand to keep us out of the last war. In August, 1914, few could have conceived that America would be dragged into a European conflict in which we had no original part and the ramifications of which we did not even understand. Even as late as November, 1916, President Wilson was reelected because he “kept us out of war.” Yet five months later we were fighting to “save the world for democracy” in the “war to end war.”

In the light of that experience, and in the red glow of war fires burning in the old countries, it is high time we gave some thought to the hard, practical question of just how we propose to stay out of present and future international conflicts. No one who has made an honest attempt to face the issue will assert that there is an easy answer. But if we have learned anything at all, we know the inevitable and tragic end to a policy of drifting and trusting to luck. We know that however strong is the will of the American people to refrain from mixing in other people’s quarrels, that will can be made effective only if we have a sound, definite policy from the beginning.

Such a policy must be built upon a program to safeguard our neutrality. No lesson of the World War is more clear than that such a policy cannot be improvised after war breaks out. It must be determined in advance, before it is too late to apply reason. I contend with all possible earnestness that if we want to avoid being drawn into this war now forming, or any other future war, we must formulate a definite, workable policy of neutral relations with belligerent nations.

Some of us in the Senate, particularly the members of the Munitions Investigation Committee, have delved rather deeply into the matter of how the United States has been drawn into past wars, and what forces are at work to frighten us again into the traps set by Mars. As a result of these studies, Senator Nye and I introduced the three proposals for neutrality legislation which were debated so vigorously in the last session of the Congress. A part of that legislative program was battered through both houses in the closing hours of the session late in August; a very vital part of it was held in abeyance.

Senator Nye and I made no claims then, and make none now, that the neutrality proposals will provide an absolute and infallible guarantee against our involvement in war. But we do believe that the United States can stay out of war if it wants to, and if its citizens understand what is necessary to preserve our neutrality. We feel that the temporary legislation already passed and the legislation we shall vigorously push at the coming session of the Congress point the only practical way . . . .

The act is to terminate February 29, 1936. It is a stop-gap only. But it is pointing the way we intend to go.

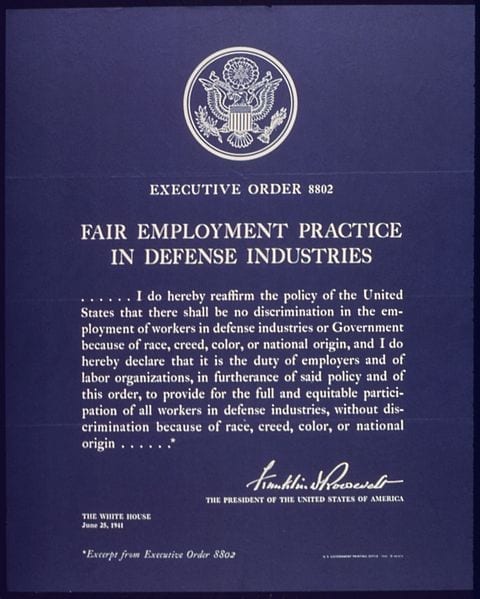

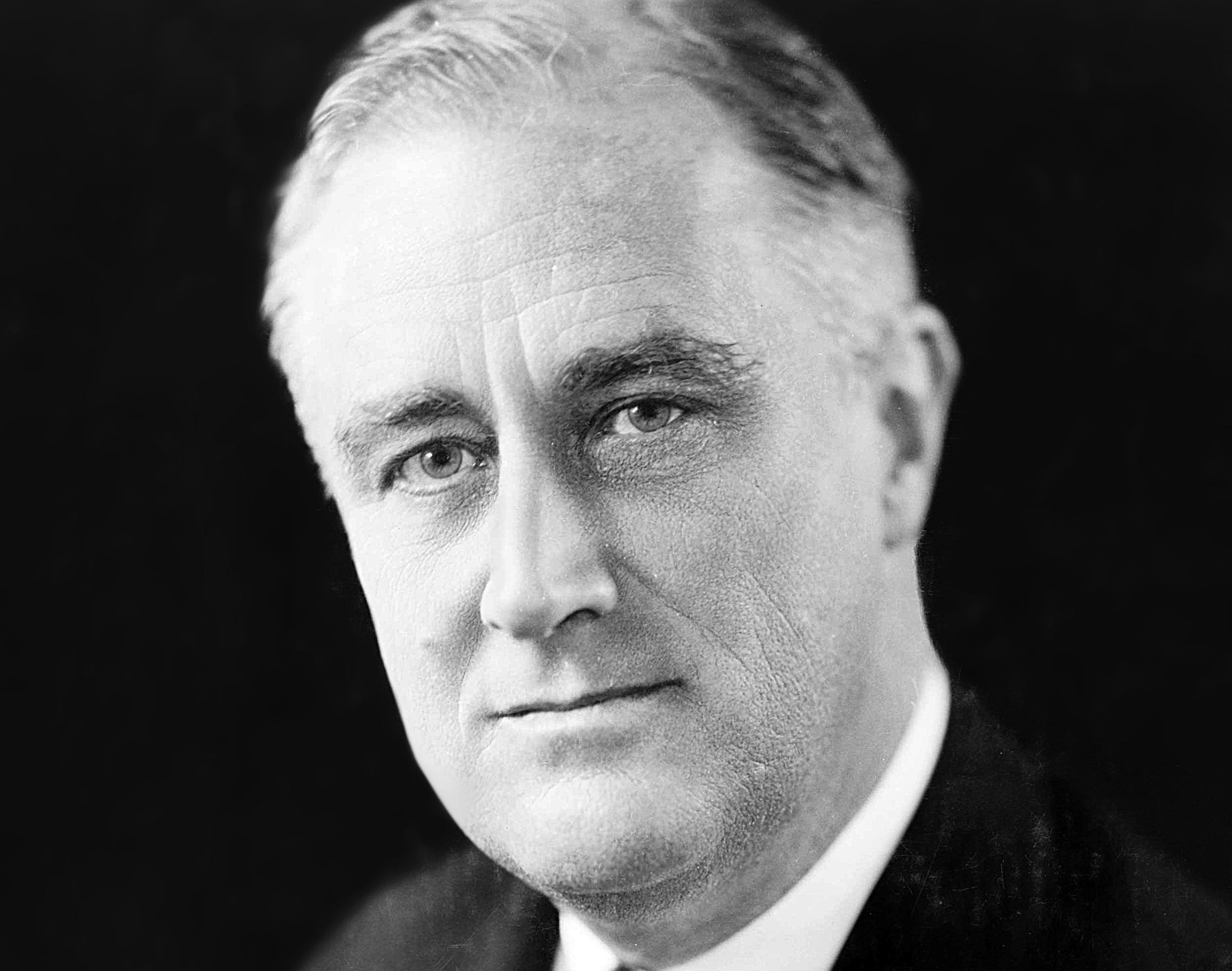

The President is empowered to enumerate definitely the arms, munitions, and implements of war, the exportation of which is prohibited by this act. On September 27th President Roosevelt made this enumeration in a proclamation, following closely the list submitted to the disarmament conference at Geneva in our government’s proposals for international control of the munitions industry. A National Munitions Control Board has been established, composed of the Secretaries of State, Treasury, War, Navy, and Commerce, with the administration of the board in the Department of State. It is contemplated that by November 29th, when the Act takes effect, the manufacturers and exporters of war implements will all be listed in the office of this board. After that date such materials as are specified may not be exported without a license issued by the board to cover such shipment. This will, obviously, permit the government to prohibit shipments to belligerent nations. The act makes it unlawful for any American vessel to “carry arms, ammunition, or implements of war to any port of the belligerent countries named in such proclamation as being at war, or to any neutral port for transshipment to, or for use in, a belligerent country.”

Further provisions of the act empower the President to restrict the use of American ports and waters to submarines of foreign nations in the event such use might disturb our position of neutrality, and to proclaim the conditions under which American citizens on belligerent ships during war must travel entirely at their own risk.

Two provisions from our original program failed to pass: prohibition of loans and credits to belligerent nations, and the application of strict embargoes upon contraband materials other than munitions and war implements. . . .

I have called the present neutrality act a stop-gap. But it has not stopped the activities of our American war-munitions makers anxious for profits from imminent conflicts. Reports from centers of manufacturing and exporting of war implements all tell the same story: there is a boom in war preparations. Chambers of commerce in cities with large war-materials plants proudly report reemployment of skilled munitions makers in large numbers, the stepping up of output to as high as three hundred per cent, the rushing to completion of new additions to plants. Day-and-night shifts in the brass and copper mills, rising prices and large shipments of these metals, and the acquisition of large capital for immediate wartime scale production, all indicate that Mars has waved his magic wand in our direction.

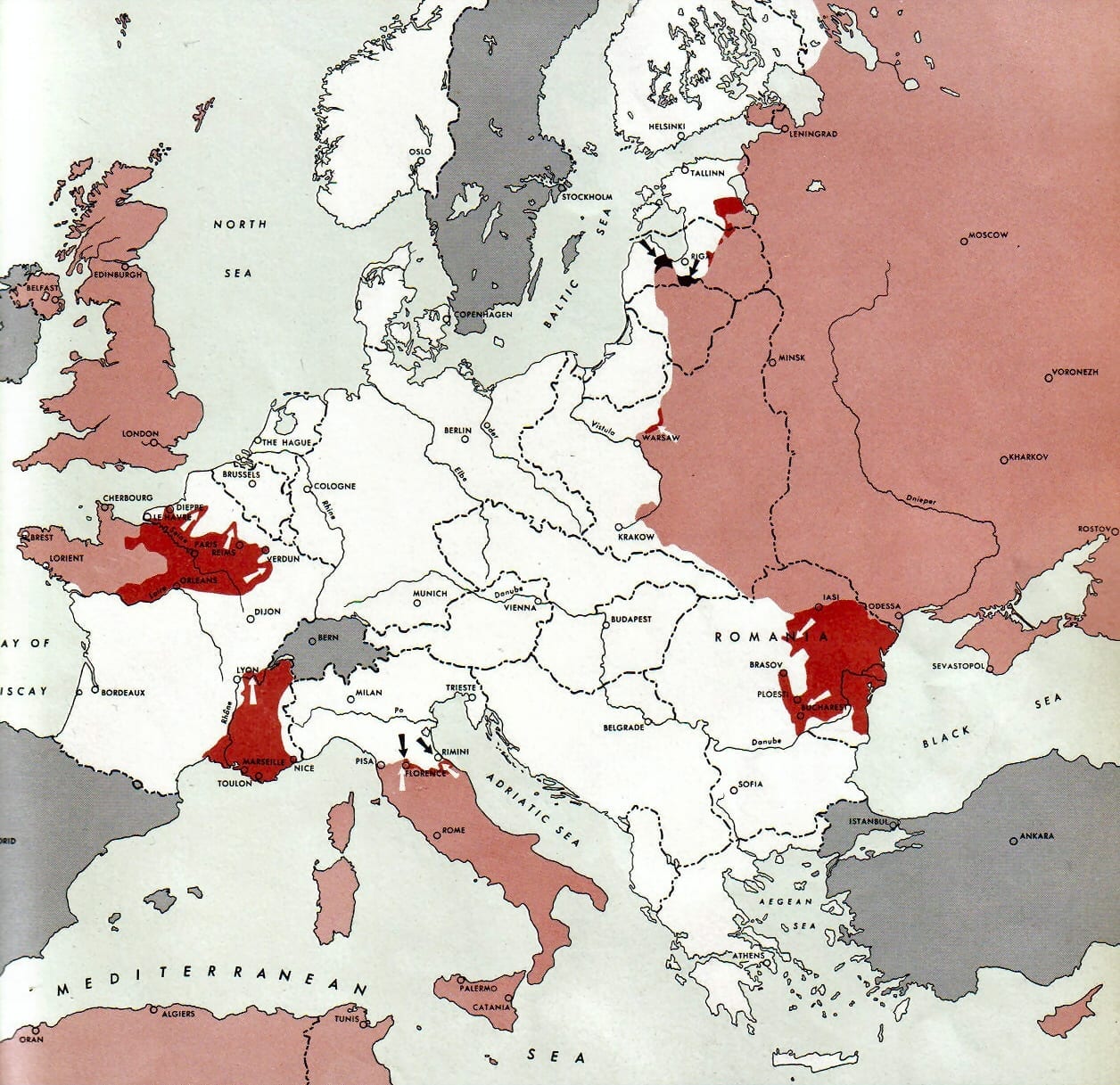

Where are these war-implements shipments going? There is no proof that the munitions makers are trying to “beat the embargo” which will prohibit shipments to belligerents after November 29th, but it stands to reason they are making hay while the sun shines. Our Munitions Investigation Committee has not had time to look into immediate developments, but it needs no stretch of imagination to contemplate the rich profits that would flow from an Italian-Ethiopian war,1 with England jumping into the fray against Italy, and other European nations following suit on one side or the other.

And, of course, there’s lots of war business right here at home. We have increased our expenditures on our Army and Navy in preparation for another and more dreadful war more rapidly than any European country in the period since the World War. . . .

When the Congress meets in January, facing the expiration of the neutrality act on February 29th, the battle for a practical policy of neutrality will have to be fought all over again. We who believe that the detour around another devastating war is to be found only in new conceptions of neutrality will fight for the retention of the present legislation and for the passage of the two items left out in the cold at the adjournment of the Congress.

I firmly believe, whatever the status of the Italo-Ethiopian dispute at that time, whatever the position of other European powers as belligerents or as neutrals, that the United States of America cannot turn back to a policy of so-called neutrality that finally pulls us into conflict with one or all the belligerents. Surely it is obvious that the legislation forcing mandatory embargoes upon war materials will serve to check the growth of another vast munitions trade with warring powers and the dangers that follow a swing of our foreign trade in favor of our munitions customers and against those who cannot purchase the munitions. Why shall we contend for embargoes upon contraband articles as well, and prohibition of loans and credits to belligerents? Because it takes these two items to complete any sort of workable neutrality program. If we are in earnest about neutrality we may as well plan to be neutral. . . .

Let us foresee that under conditions of modern warfare everything supplied to the enemy population has the same effect as supplies to the enemy army, and will become contraband. Food, clothing, lumber, leather, chemicals – everything, in fact, with the possible exception of sporting goods and luxuries (and these aid in maintaining civilian “morale”) – are as important aids to winning the war as are munitions. Let us foresee also that our ships carrying contraband will be seized, bombed from the air or sunk by submarines. Let us not claim as a right what is an impossibility. The only way we can maintain our neutral rights is to fight the whole world. If we are not prepared to do that we can only pretend to enforce our rights against one side, and go to war to defend them against the other side. We might at least abandon pretense.

On the matter of loans and credits to belligerents, the train of events which pulled us into the World War is equally significant. Correspondence which our Munitions Investigation Committee discovered in the files of the State Department offers illuminating proof that there can be no true neutrality when our nation is allowed to finance one side of a foreign war. One letter, written by Secretary Robert Lansing to President Wilson, dated September 5, 1915, lucidly points out that loans for the Allies were absolutely necessary to enable them to pay for the tremendous trade in munitions, war materials generally, food stuffs, and the like, or else that trade would have to stop. He declared that the Administration’s “true spirit of neutrality” must not stand in the way of the demands of commerce. About one month later the first great loan – the Anglo-French loan of $500,000,000 – was floated by a syndicate headed by J. P. Morgan and Company. This company had been the purchasing agents for Allied supplies in the United States since early in 1915. Other loans to the Allied powers quickly followed. . . .

“But, think of the profits!” cry our theorists. “America will never give up her lucrative trade in munitions and necessities of life when war starts!”. . .

Just who profited from the last war? Labor got some of the crumbs in the form of high wages and steady jobs. But where is labor to-day with its fourteen million unemployed? Agriculture received high prices for its products during the period of the War and has been paying the price of that brief inflation in the worst and longest agricultural depression in all history. Industry made billions in furnishing the necessities of war to the belligerents and then suffered terrific re-action like the dope addict’s morning after. War and depression – ugly, misshapen inseparable twins – must be considered together. Each is a catapult for the other. The present world-wide depression is a direct result of the World War. Every war in modern history has been followed by a major depression.

Therefore I say, let the man seeking profits from war or the war-torn countries do so at his own risk. . . .

If there are those so brave as to risk getting us into war by traveling in the war zones – if there are those so valiant that they do not care how many people are killed as a result of their traveling, let us tell them, and let us tell the world that from now on their deaths will be a misfortune to their own families alone, not to the whole nation.

The profiteers and others who oppose any rational neutrality shout: “You would sacrifice our national honor!” Some declare we are about to haul down the American flag, and in a future war the belligerents will trample on our rights and treat us with contempt. Some of these arguments are trundled out by our naval bureaucracy. The admirals, I am told, objected strenuously when the State Department suggested a new policy of neutrality somewhat along these lines.

I deny with every fiber of my being that our national honor demands that we must sacrifice the flower of our youth to safeguard the profits of a privileged few. I deny that it is necessary to turn back the hands of civilization to maintain our national honor. I repudiate any such definition of honor. Is it not time for every lover of our country to do the same thing?

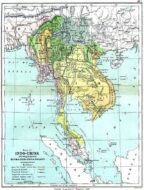

- 1. The Second Italo-Ethiopian war had begun when Italian forces invaded Ethiopia from Italian Somaliland in October 1935. The English and French would not move to stop the Italian incursion into Ethiopia, fearing that doing so would push Italy into alliance with Germany.

Neutrality Act of 1937

May 01, 1937

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.