No related resources

Introduction

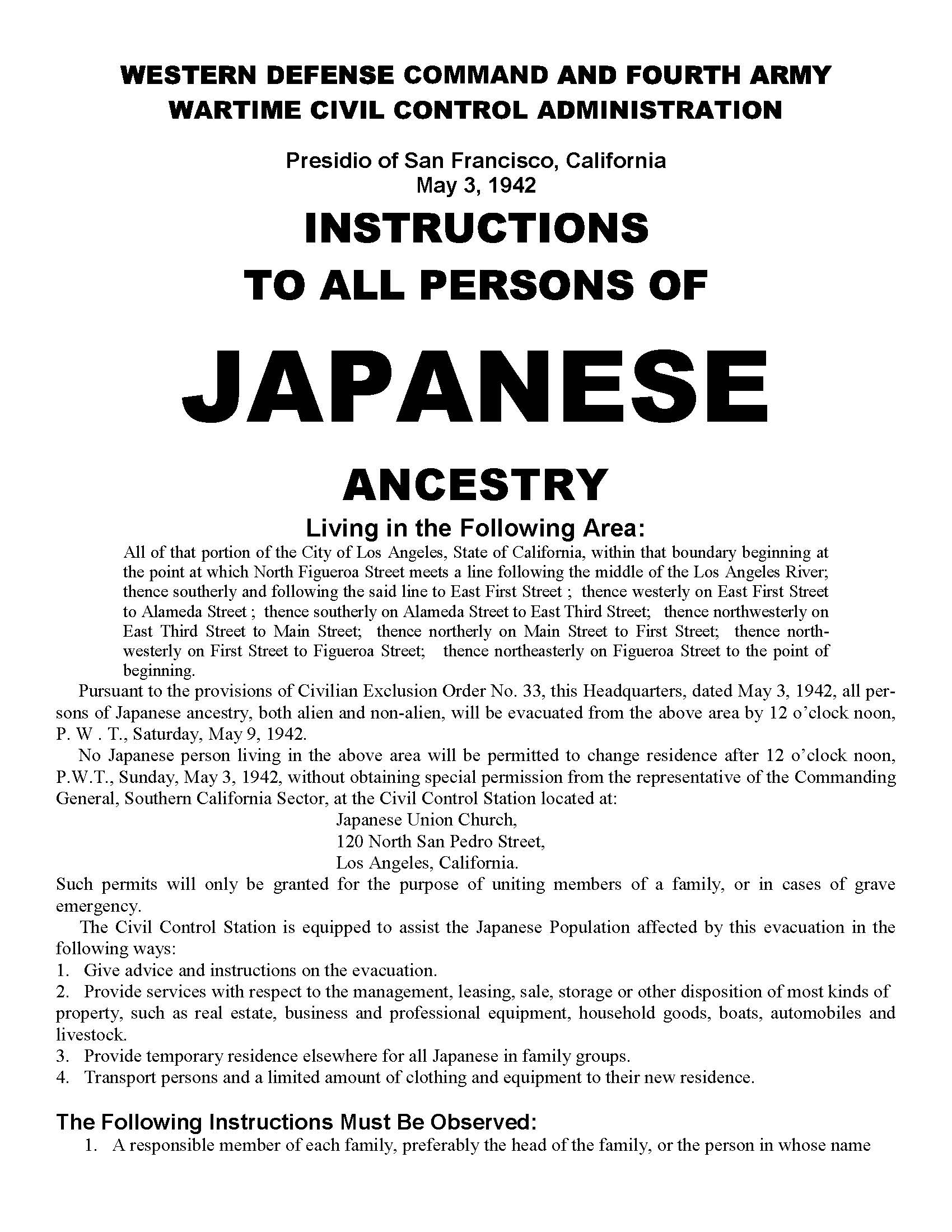

In Wickard v. Filburn, the Supreme Court considered whether Congress possessed the authority under the commerce clause (Article I, section 8, clause 3) to prohibit a farmer from growing wheat for personal consumption. Congress passed a number of bills during the Depression years aimed at protecting the fragile economy. In passing the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1938 and amending that act in 1941, Congress sought to stabilize the price of wheat by directing the secretary of agriculture to set quotas for how much wheat could be harvested across the country, within particular states, and on specific farms. Roscoe Filburn, an Ohio farmer, exceeded his quota and was fined; but he argued that the excess wheat was for personal consumption and not intended for sale. He therefore contended that this activity was “beyond the reach of congressional power under the Commerce Clause.”

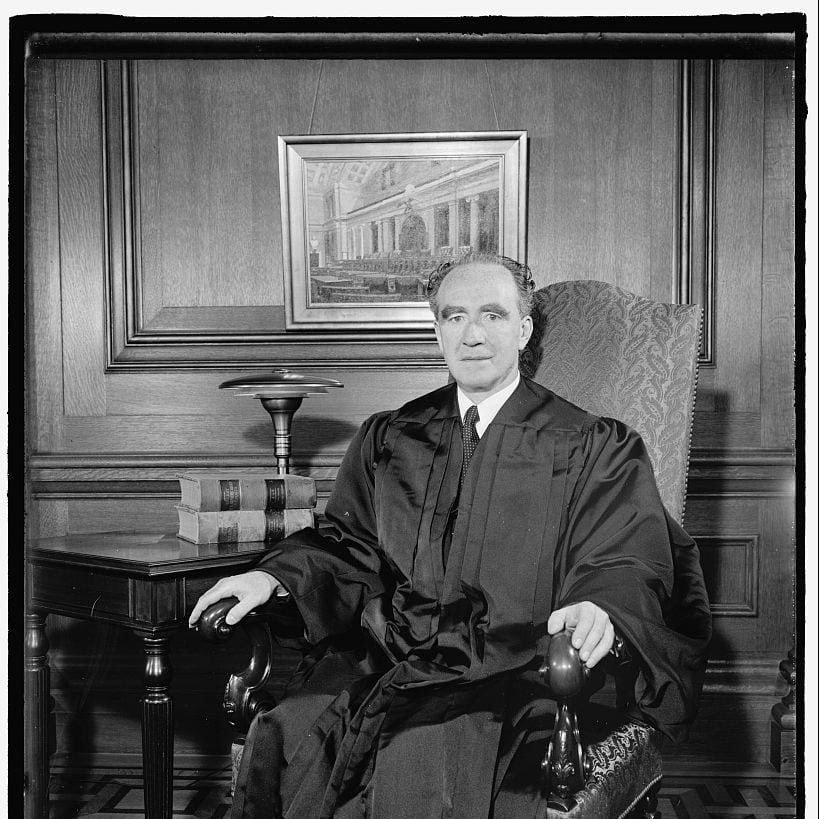

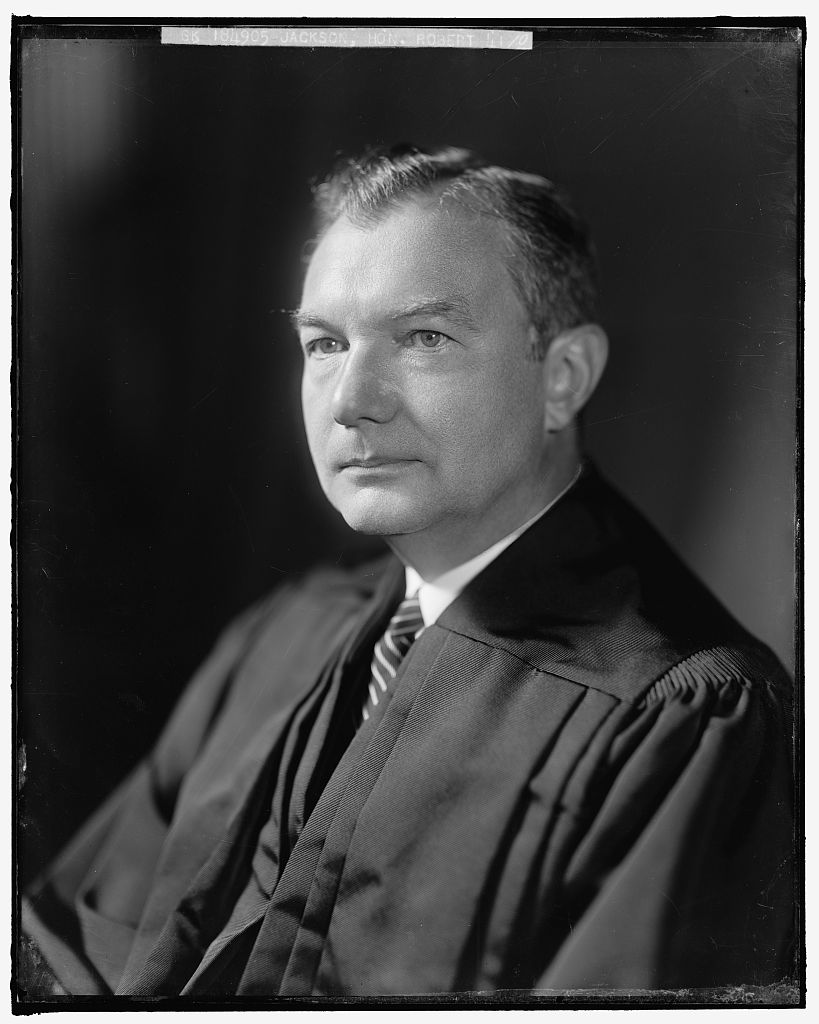

In the most far-reaching application of the federal government’s power to regulate commerce ever found in a Supreme Court decision, the Court concluded that the commerce clause authorized congressional regulation of noncommercial activities if they had a substantial effect on commerce. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Robert H. Jackson (1892–1954) stressed that one purpose of the AAA was to increase the price of wheat. “Home-grown wheat … competes with wheat in commerce.” Therefore, the commerce clause gave Congress the power to tell Mr. Filburn how much wheat he could grow.

Source: 317 U.S. 111 (1942), https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/317/111.

Mr. Justice JACKSON delivered the opinion of the Court.

... The appellee for many years past has owned and operated a small farm in Montgomery County, Ohio, maintaining a herd of dairy cattle, selling milk, raising poultry, and selling poultry and eggs. It has been his practice to raise a small acreage of winter wheat, sown in the fall and harvested in the following July; to sell a portion of the crop; to feed part to poultry and livestock on the farm, some of which is sold; to use some in making flour for home consumption; and to keep the rest for the following seeding. The intended disposition of the crop here involved has not been expressly stated.

In July of 1940, pursuant to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, as then amended, there were established for the appellee’s 1941 crop a wheat acreage allotment of 11.1 acres and a normal yield of 20.1 bushels of wheat an acre. He was given notice of such allotment in July of 1940 before the fall planting of his 1941 crop of wheat, and again in July of 1941, before it was harvested. He sowed, however, 23 acres, and harvested from his 11.9 acres of excess acreage 239 bushels, which under the terms of the Act as amended on May 26, 1941, constituted farm marketing excess, subject to a penalty of 49 cents a bushel, or $117.11 in all. The appellee has not paid the penalty and he has not postponed or avoided it by storing the excess under regulations of the secretary of agriculture, or by delivering it up to the secretary. The committee, therefore, refused him a marketing card, which was, under the terms of regulations promulgated by the secretary, necessary to protect a buyer from liability to the penalty and upon its protecting lien.

The general scheme of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 as related to wheat is to control the volume moving in interstate and foreign commerce in order to avoid surpluses and shortages and the consequent abnormally low or high wheat prices and obstructions to commerce. Within prescribed limits and by prescribed standards the secretary of agriculture is directed to ascertain and proclaim each year a national acreage allotment for the next crop of wheat, which is then apportioned to the states and their counties, and is eventually broken up into allotments for individual farms....

It is urged that under the commerce clause of the Constitution, Article I, § 8, clause 3, Congress does not possess the power it has in this instance sought to exercise. The question would merit little consideration since our decision in United States v. Darby,1 sustaining the federal power to regulate production of goods for commerce except for the fact that this Act extends federal regulation to production not intended in any part for commerce but wholly for consumption on the farm. The Act includes a definition of “market” and its derivatives so that as related to wheat in addition to its conventional meaning it also means to dispose of “by feeding (in any form) to poultry or livestock which, or the products of which, are sold, bartered, or exchanged, or to be so disposed of.” Hence, marketing quotas not only embrace all that may be sold without penalty but also what may be consumed on the premises. Wheat produced on excess acreage is designated as “available for marketing” as so defined and the penalty is imposed thereon. Penalties do not depend upon whether any part of the wheat either within or without the quota is sold or intended to be sold. The sum of this is that the federal government fixes a quota including all that the farmer may harvest for sale or for his own farm needs, and declares that wheat produced on excess acreage may neither be disposed of nor used except upon payment of the penalty or except it is stored as required by the Act or delivered to the secretary of agriculture.

Appellee says that this is a regulation of production and consumption of wheat. Such activities are, he urges, beyond the reach of congressional power under the commerce clause, since they are local in character, and their effects upon interstate commerce are at most “indirect.” In answer the Government argues that the statute regulates neither production nor consumption, but only marketing; and, in the alternative, that if the Act does go beyond the regulation of marketing it is sustainable as a “necessary and proper” implementation of the power of Congress over interstate commerce....

The maintenance by government regulation of a price for wheat undoubtedly can be accomplished as effectively by sustaining or increasing the demand as by limiting the supply. The effect of the statute before us is to restrict the amount which may be produced for market and the extent, as well, to which one may forestall resort to the market by producing to meet his own needs. That appellee’s own contribution to the demand for wheat may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his contribution, taken together with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.

It is well established by decisions of this Court that the power to regulate commerce includes the power to regulate the prices at which commodities in that commerce are dealt in and practices affecting such prices. One of the primary purposes of the Act in question was to increase the market price of wheat and to that end to limit the volume thereof that could affect the market. It can hardly be denied that a factor of such volume and variability as home-consumed wheat would have a substantial influence on price and market conditions. This may arise because being in marketable condition such wheat overhangs the market and if induced by rising prices tends to flow into the market and check price increases. But if we assume that it is never marketed, it supplies a need of the man who grew it which would otherwise be reflected by purchases in the open market. Home-grown wheat in this sense competes with wheat in commerce. The stimulation of commerce is a use of the regulatory function quite as definitely as prohibitions or restrictions thereon. This record leaves us in no doubt that Congress may properly have considered that wheat consumed on the farm where grown if wholly outside the scheme of regulation would have a substantial effect in defeating and obstructing its purpose to stimulate trade therein at increased prices....

- 1. United States v. Darby Lumber Co., 312 U.S. 100 (1941).

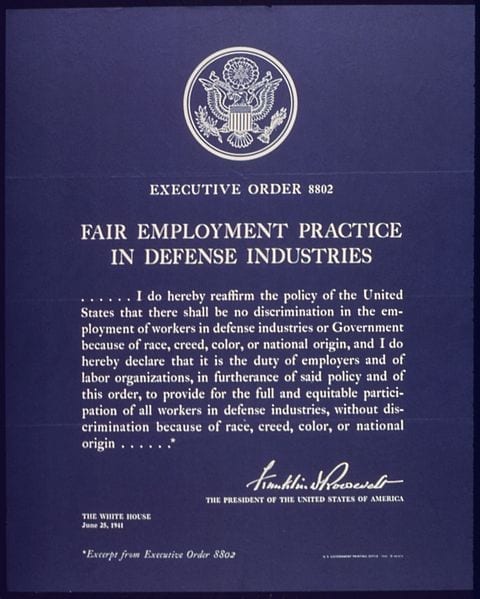

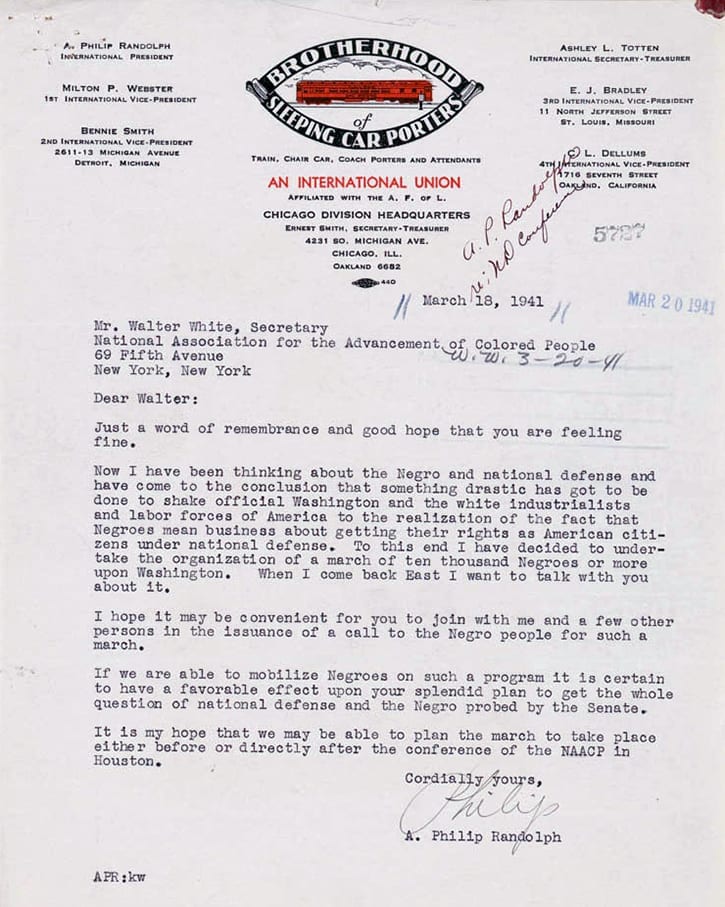

Why Should We March?

November 30, 1942

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.