Introduction

Near v. Minnesota is the Supreme Court’s first landmark case on freedom of the press. Jay M. Near and Howard Guilford were publishers of a Minneapolis newspaper known as the Saturday Press, which accused the Minneapolis police of conniving with Jewish gangsters. Their anti-Semitic rant called on law-abiding Jews to rid “THE RODENTS OF THEIR OWN RACE,” alleging that “practically every vendor of vile hooch, every owner of a moonshine still, every snake-faced gangster and embryonic yegg in the Twin Cities is a JEW. . . . If the people of Jewish faith in Minneapolis wish to avoid criticism of these vermin whom I rightfully call ‘Jews’ they can easily do so BY THEMSELVES CLEANING HOUSE.” For these remarks and others, Near and Guilford were prosecuted under a Minnesota Public Nuisance Law that punished “any person who . . . shall be engaged in the business of regularly or customarily producing, publishing, or circulating, having in possession, selling, or giving away . . . a malicious, scandalous, and defamatory newspaper, magazine, or other periodical.” A temporary restraining order was granted to prevent further publication. Notwithstanding their virulently anti-Semitic message, the Saturday Press stories exposed criminal activity that led to a local gangster’s conviction. Guilford survived two attempted assassinations that were likely retaliations from organized crime. A permanent injunction was issued after the temporary restraining order. The Minnesota Supreme Court upheld both rulings.

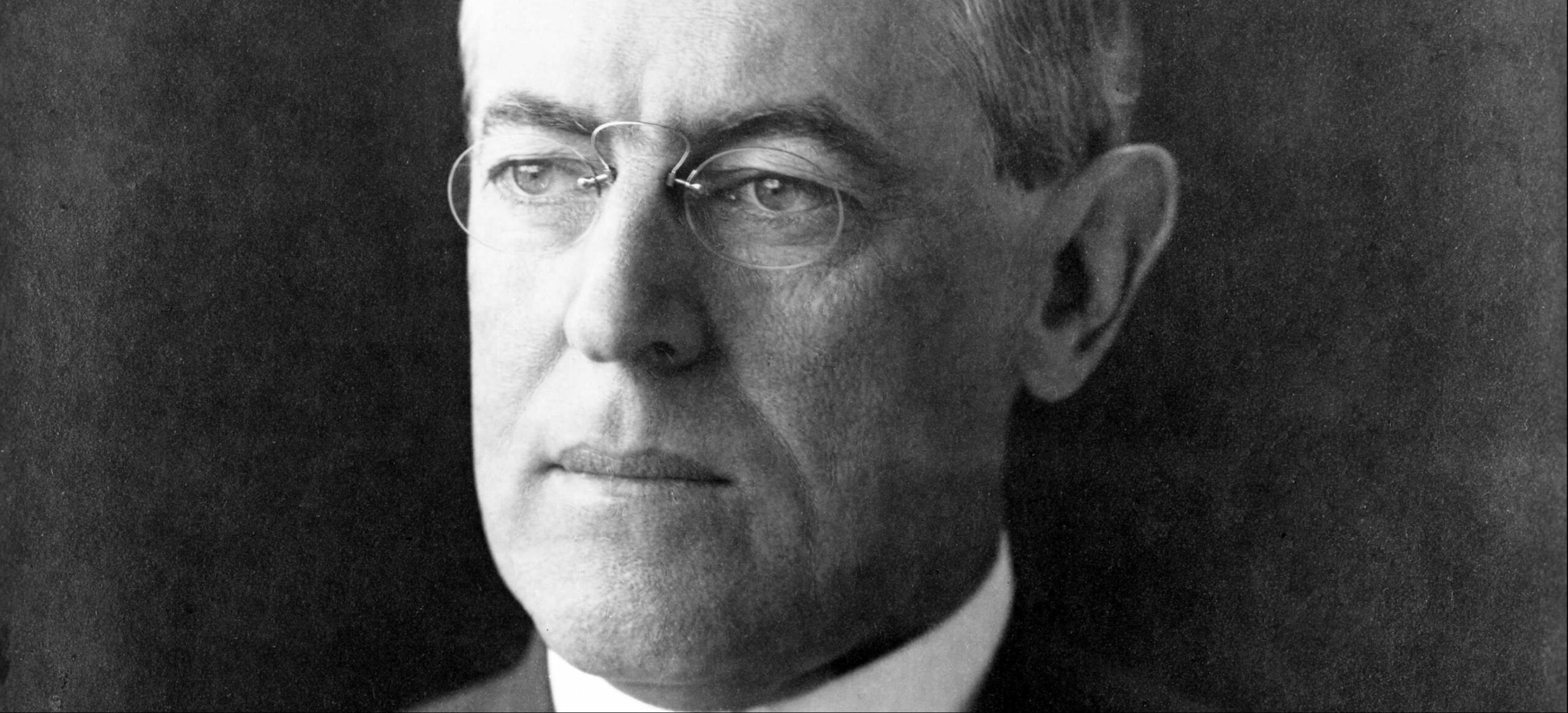

Writing for the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes (1862–1948) overturned the injunction as an illegal prior restraint—the censorship of material before publication—in violation of the First Amendment. Anglo-American law has a strong presumption against prior restraint dating back to England’s restrictive licensing laws. Indeed, Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, one of the most widely read works at the time of America’s founding, included a definite rejection of prior restraint that was shared by many of the Founders. Though written nearly a century ago, Hughes’ opinion is particularly valuable in presenting a historical treasure trove on the Founders’ view of liberty of the press. The press, he argued, was more urgently needed in his own time than in the Founding given the growth of government and the complex challenges of twentieth-century urban-industrial life.

Source: 283 U.S. 697, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/283/697.

- CHIEF JUSTICE HUGHES delivered the opinion of the Court.

Chapter 285 of the Session Laws of Minnesota for the year 1925 provides for the abatement, as a public nuisance, of a “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory newspaper, magazine, or other periodical.” . . .

1This statute, for the suppression as a public nuisance of a newspaper or periodical, is unusual, if not unique, and raises questions of grave importance transcending the local interests involved in the particular action. It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press, and of speech, is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action. It was found impossible to conclude that this essential personal liberty of the citizen was left unprotected by the general guaranty of fundamental rights of person and property. In maintaining this guaranty, the authority of the state to enact laws to promote the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of its people is necessarily admitted. The limits of this sovereign power must always be determined with appropriate regard to the particular subject of its exercise. . . . Liberty of speech, and of the press, is also not an absolute right, and the state may punish its abuse (Whitney v. California).[1] . . . Liberty, in each of its phases, has its history and connotation, and, in the present instance, the inquiry is as to the historic conception of the liberty of the press and whether the statute under review violates the essential attributes of that liberty. . . .

If we cut through mere details of procedure, the operation and effect of the statute, in substance, is that public authorities may bring the owner or publisher of a newspaper or periodical before a judge upon a charge of conducting a business of publishing scandalous and defamatory matter—in particular, that the matter consists of charges against public officers of official dereliction—and, unless the owner or publisher is able and disposed to bring competent evidence to satisfy the judge that the charges are true and are published with good motives and for justifiable ends, his newspaper or periodical is suppressed and further publication is made punishable as a contempt. This is of the essence of censorship.

The question is whether a statute authorizing such proceedings in restraint of publication is consistent with the conception of the liberty of the press as historically conceived and guaranteed. In determining the extent of the constitutional protection, it has been generally, if not universally, considered that it is the chief purpose of the guaranty to prevent previous restraints upon publication. The struggle in England, directed against the legislative power of the licenser, resulted in renunciation of the censorship of the press. The liberty deemed to be established was thus described by Blackstone:

The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.[2]

The distinction was early pointed out between the extent of the freedom with respect to censorship under our constitutional system and that enjoyed in England. Here, as Madison said,

the great and essential rights of the people are secured against legislative as well as against executive ambition. They are secured not by laws paramount to prerogative, but by constitutions paramount to laws. This security of the freedom of the press requires that it should be exempt not only from previous restraint by the Executive, a in Great Britain, but from legislative restraint also.[3] . . .

The criticism upon Blackstone’s statement [by Madison and others] has not been because immunity from previous restraint upon publication has not been regarded as deserving of special emphasis, but chiefly because that immunity cannot be deemed to exhaust the conception of the liberty guaranteed by state and federal constitutions. The point of criticism has been “that the mere exemption from previous restraints cannot be all that is secured by the constitutional provisions,” and that “the liberty of the press might be rendered a mockery and a delusion, and the phrase itself a byword, if, while every man was at liberty to publish what he pleased, the public authorities might nevertheless punish him for harmless publications.”[4]

But it is recognized that punishment for the abuse of the liberty accorded to the press is essential to the protection of the public, and that the common-law rules that subject the libeler to responsibility for the public offense, as well as for the private injury, are not abolished by the protection extended in our constitutions. The law of criminal libel rests upon that secure foundation. There is also the conceded authority of courts to punish for contempt when publications directly tend to prevent the proper discharge of judicial functions. In the present case, we have no occasion to inquire as to the permissible scope of subsequent punishment. For whatever wrong the appellant has committed or may commit by his publications the state appropriately affords both public and private redress by its libel laws. As has been noted, the statute in question does not deal with punishments; it provides for no punishment, except in case of contempt for violation of the court’s order, but for suppression and injunction, that is, for restraint upon publication.

The objection has also been made that the principle as to immunity from previous restraint is stated too broadly, if every such restraint is deemed to be prohibited. That is undoubtedly true; the protection even as to previous restraint is not absolutely unlimited. But the limitation has been recognized only in exceptional cases: “When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right” (Schenck v. United States).[5] No one would question but that a government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops. On similar grounds, the primary requirements of decency may be enforced against obscene publications. The security of the community life may be protected against incitements to acts of violence and the overthrow by force of orderly government. . . .

The exceptional nature of its limitations places in a strong light the general conception that liberty of the press, historically considered and taken up by the federal Constitution, has meant, principally, although not exclusively, immunity from previous restraints or censorship. The conception of the liberty of the press in this country had broadened with the exigencies of the colonial period and with the efforts to secure freedom from oppressive administration. That liberty was especially cherished for the immunity it afforded from previous restraint of the publication of censure of public officers and charges of official misconduct. As was said by Chief Justice Parker, in Commonwealth v. Blanding, with respect to the constitution of Massachusetts:

Besides, it is well understood, and received as a commentary on this provision for the liberty of the press, that it was intended to prevent all such previous restraints upon publications as had been practiced by other governments, and in early times here, to stifle the efforts of patriots towards enlightening their fellow subjects upon their rights and the duties of rulers. The liberty of the press was to be unrestrained, but he who used it was to be responsible in case of its abuse.

In the letter sent by the Continental Congress (October 26, 1774) to the Inhabitants of Quebec, referring to the “five great rights,” it was said:

The last right we shall mention regards the freedom of the press. The importance of this consists, besides the advancement of truth, science, morality, and arts in general, in its diffusion of liberal sentiments on the administration of Government, its ready communication of thoughts between subjects, and its consequential promotion of union among them whereby oppressive officers are shamed or intimidated into more honorable and just modes of conducting affairs.

Madison, who was the leading spirit in the preparation of the First Amendment of the federal Constitution, thus described the practice and sentiment which led to the guaranties of liberty of the press in state constitutions:

In every State, probably, in the Union, the press has exerted a freedom in canvassing the merits and measures of public men of every description which has not been confined to the strict limits of the common law. On this footing the freedom of the press has stood; on this footing it yet stands. . . . Some degree of abuse is inseparable from the proper use of everything, and in no instance is this more true than in that of the press. It has accordingly been decided by the practice of the states that it is better to leave a few of its noxious branches to their luxuriant growth than, by pruning them away, to injure the vigor of those yielding the proper fruits. And can the wisdom of this policy be doubted by any who reflect that to the press alone, checkered as it is with abuses, the world is indebted for all the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity over error and oppression; who reflect that to the same beneficent source the United States owe much of the lights which conducted them to the ranks of a free and independent nation, and which have improved their political system into a shape so auspicious to their happiness? Had “Sedition Acts,” forbidding every publication that might bring the constituted agents into contempt or disrepute, or that might excite the hatred of the people against the authors of unjust or pernicious measures, been uniformly enforced against the press, might not the United States have been languishing at this day under the infirmities of a sickly Confederation? Might they not, possibly, be miserable colonies, groaning under a foreign yoke?[6]

The fact that, for approximately 150 years, there has been almost an entire absence of attempts to impose previous restraints upon publications relating to the malfeasance of public officers is significant of the deep-seated conviction that such restraints would violate constitutional right. Public officers, whose character and conduct remain open to debate and free discussion in the press, find their remedies for false accusations in actions under libel laws providing for redress and punishment, and not in proceedings to restrain the publication of newspapers and periodicals. The general principle that the constitutional guaranty of the liberty of the press gives immunity from previous restraints has been approved in many decisions under the provisions of state constitutions.

The importance of this immunity has not lessened. While reckless assaults upon public men, and efforts to bring obloquy upon those who are endeavoring faithfully to discharge official duties, exert a baleful influence and deserve the severest condemnation in public opinion, it cannot be said that this abuse is greater, and it is believed to be less, than that which characterized the period in which our institutions took shape. Meanwhile, the administration of government has become more complex, the opportunities for malfeasance and corruption have multiplied, crime has grown to most serious proportions, and the danger of its protection by unfaithful officials and of the impairment of the fundamental security of life and property by criminal alliances and official neglect, emphasizes the primary need of a vigilant and courageous press, especially in great cities. The fact that the liberty of the press may be abused by miscreant purveyors of scandal does not make any the less necessary the immunity of the press from previous restraint in dealing with official misconduct. Subsequent punishment for such abuses as may exist is the appropriate remedy consistent with constitutional privilege. . . .

The statute in question cannot be justified by reason of the fact that the publisher is permitted to show, before injunction issues, that the matter published is true and is published with good motives and for justifiable ends. If such a statute, authorizing suppression and injunction on such a basis, is constitutionally valid, it would be equally permissible for the legislature to provide that at any time the publisher of any newspaper could be brought before a court, or even an administrative officer (as the constitutional protection may not be regarded as resting on mere procedural details), and required to produce proof of the truth of his publication, or of what he intended to publish, and of his motives, or stand enjoined. If this can be done, the legislature may provide machinery for determining in the complete exercise of its discretion what are justifiable ends, and restrain publication accordingly. And it would be but a step to a complete system of censorship. The recognition of authority to impose previous restraint upon publication in order to protect the community against the circulation of charges of misconduct, and especially of official misconduct, necessarily would carry with it the admission of the authority of the censor against which the constitutional barrier was erected. The preliminary freedom, by virtue of the very reason for its existence, does not depend, as this Court has said, on proof of truth.

Equally unavailing is the insistence that the statute is designed to prevent the circulation of scandal which tends to disturb the public peace and to provoke assaults and the commission of crime. Charges of reprehensible conduct, and in particular of official malfeasance, unquestionably create a public scandal, but the theory of the constitutional guaranty is that even a more serious public evil would be caused by authority to prevent publication.

To prohibit the intent to excite those unfavorable sentiments against those who administer the Government is equivalent to a prohibition of the actual excitement of them, and to prohibit the actual excitement of them is equivalent to a prohibition of discussions having that tendency and effect, which, again, is equivalent to a protection of those who administer the Government, if they should at any time deserve the contempt or hatred of the people, against being exposed to it by free animadversions on their characters and conduct.[7]

There is nothing new in the fact that charges of reprehensible conduct may create resentment and the disposition to resort to violent means of redress, but this well-understood tendency did not alter the determination to protect the press against censorship and restraint upon publication. As was said in New Yorker Staats-Zeitung v. Nolan: “If the township may prevent the circulation of a newspaper for no reason other than that some of its inhabitants may violently disagree with it, and resent its circulation by resorting to physical violence, there is no limit to what may be prohibited.”

The danger of violent reactions becomes greater with effective organization of defiant groups resenting exposure, and if this consideration warranted legislative interference with the initial freedom of publication, the constitutional protection would be reduced to a mere form of words.

For these reasons we hold the statute, so far as it authorized the proceedings in this action under clause (b) of section one, to be an infringement of the liberty of the press guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. We should add that this decision rests upon the operation and effect of the statute, without regard to the question of the truth of the charges contained in the particular periodical. The fact that the public officers named in this case, and those associated with the charges of official dereliction, may be deemed to be impeccable cannot affect the conclusion that the statute imposes an unconstitutional restraint upon publication.

Judgment reversed.

JUSTICE BUTLER, dissenting.

The decision of the Court in this case declares Minnesota and every other state powerless to restrain by injunction the business of publishing and circulating among the people malicious, scandalous, and defamatory periodicals that in due course of judicial procedure has been adjudged to be a public nuisance. It gives to freedom of the press a meaning and a scope not heretofore recognized, and construes “liberty” in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to put upon the states a federal restriction that is without precedent. . . .

The act was passed in the exertion of the state’s power of police, and this court is, by well-established rule, required to assume, until the contrary is clearly made to appear, that there exists in Minnesota a state of affairs that justifies this measure for the preservation of the peace and good order of the state. . . .

The publications themselves disclose the need and propriety of the legislation. They show:

The long criminal career of the Twin City Reporter—if it is, in fact, as described by defendants—and the arming and shooting arising out of the publication of the Saturday Press, serve to illustrate the kind of conditions, in respect of the business of publishing malicious, scandalous, and defamatory periodicals, by which the state legislature presumably was moved to enact the law in question. It must be deemed appropriate to deal with conditions existing in Minnesota.

It is of the greatest importance that the states shall be untrammeled and free to employ all just and appropriate measures to prevent abuses of the liberty of the press.

In his work on the Constitution (5th ed.), Justice Story, expounding the First Amendment, which declares “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press,” said (§ 1880):

That this amendment was intended to secure to every citizen an absolute right to speak, or write, or print whatever he might please, without any responsibility, public or private, therefor is a supposition too wild to be indulged by any rational man. This would be to allow to every citizen a right to destroy at his pleasure the reputation, the peace, the property, and even the personal safety of every other citizen. A man might, out of mere malice and revenge, accuse another of the most infamous crimes; might excite against him the indignation of all his fellow citizens by the most atrocious calumnies; might disturb, nay, overturn, all his domestic peace, and embitter his parental affections; might inflict the most distressing punishments upon the weak, the timid, and the innocent; might prejudice all a man’s civil, and political, and private rights, and might stir up sedition, rebellion, and treason even against the government itself in the wantonness of his passions or the corruption of his heart. Civil society could not go on under such circumstances. Men would then be obliged to resort to private vengeance to make up for the deficiencies of the law, and assassination and savage cruelties would be perpetrated with all the frequency belonging to barbarous and brutal communities. It is plain, then, that the language of this amendment imports no more than that every man shall have a right to speak, write, and print his opinions upon any subject whatsoever, without any prior restraint, so always that he does not injure any other person in his rights, person, property, or reputation, and so always that he does not thereby disturb the public peace or attempt to subvert the government. It is neither more nor less than an expansion of the great doctrine recently brought into operation in the law of libel, that every man shall be at liberty to publish what is true, with good motives and for justifiable ends. And, with this reasonable limitation, it is not only right in itself, but it is an inestimable privilege in a free government. Without such a limitation, it might become the scourge of the republic, first denouncing the principles of liberty and then, by rendering the most virtuous patriots odious through the terrors of the press, introducing despotism in its worst form.

The Court quotes Blackstone in support of its condemnation of the statute as imposing a previous restraint upon publication. But the previous restraints referred to by him subjected the press to the arbitrary will of an administrative officer. He describes the practice: “To subject the press to the restrictive power of a licenser, as was formerly done both before and since the revolution [of 1688], is to subject all freedom of sentiment to the prejudices of one man and make him the arbitrary and infallible judge of all controverted points in learning, religion, and government.”[8]

Story gives the history alluded to by Blackstone (§ 1882):

The art of printing, soon after its introduction, we are told, was looked upon, as well in England as in other countries, as merely a matter of state, and subject to the coercion of the Crown. It was, therefore, regulated in England by the king’s proclamations, prohibitions, charters of privilege, and licenses, and finally by the decrees of the Court of Star Chamber, which limited the number of printers and of presses which each should employ, and prohibited new publications unless previously approved by proper licensers. On the demolition of this odious jurisdiction, in 1641, the Long Parliament of Charles the First, after their rupture with that prince, assumed the same powers which the Star Chamber exercised with respect to licensing books, and during the Commonwealth (such is human frailty and the love of power even in republics), they issued their ordinances for that purpose, founded principally upon a Star Chamber decree of 1637. After the restoration of Charles the Second, a statute on the same subject was passed, copied, with some few alterations, from the parliamentary ordinances. The act expired in 1679 and was revived and continued for a few years after the revolution of 1688. Many attempts were made by the government to keep it in force, but it was so strongly resisted by Parliament that it expired in 1694 and has never since been revived.

It is plain that Blackstone taught that, under the common law, liberty of the press means simply the absence of restraint upon publication in advance as distinguished from liability, civil or criminal, for libelous or improper matter so published. And, as above shown, Story defined freedom of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment to mean that “every man shall be at liberty to publish what is true, with good motives and for justifiable ends.” His statement concerned the definite declaration of the First Amendment. It is not suggested that the freedom of press included in the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, which was adopted after Story’s definition, is greater than that protected against congressional action.

The Minnesota statute does not operate as a previous restraint on publication within the proper meaning of that phrase. It does not authorize administrative control in advance such as was formerly exercised by the licensers and censors but prescribes a remedy to be enforced by a suit in equity. In this case, there was previous publication made in the course of the business of regularly producing malicious, scandalous, and defamatory periodicals. The business and publications unquestionably constitute an abuse of the right of free press. The statute denounces the things done as a nuisance on the ground, as stated by the state supreme court, that they threaten morals, peace, and good order. There is no question of the power of the state to denounce such transgressions. . . .

- 1. Whitney v. California.

- 2. William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England: A Facsimile of the First Edition of 1765–1769 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 4:151–52.

- 3. James Madison, “The Report of 1800,” in The Papers of James Madison, ed. David B. Mattern et al. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991), 17:303–51. Madison wrote the report in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. For these acts, see the Glossary.

- 4. Thomas McIntyre Cooley, A Treatise upon the Constitutional Limitations Which Rest upon the Legislative Power of the State of the American Union (New York: Little, Brown, 1927), 885.

- 5. Schenck v. United States.

- 6. Madison, “Report of 1800.”

- 7. Madison, “Report of 1800.”

- 8. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 4:152.

Annual Message to Congress (1931)

December 08, 1931

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.