Introduction

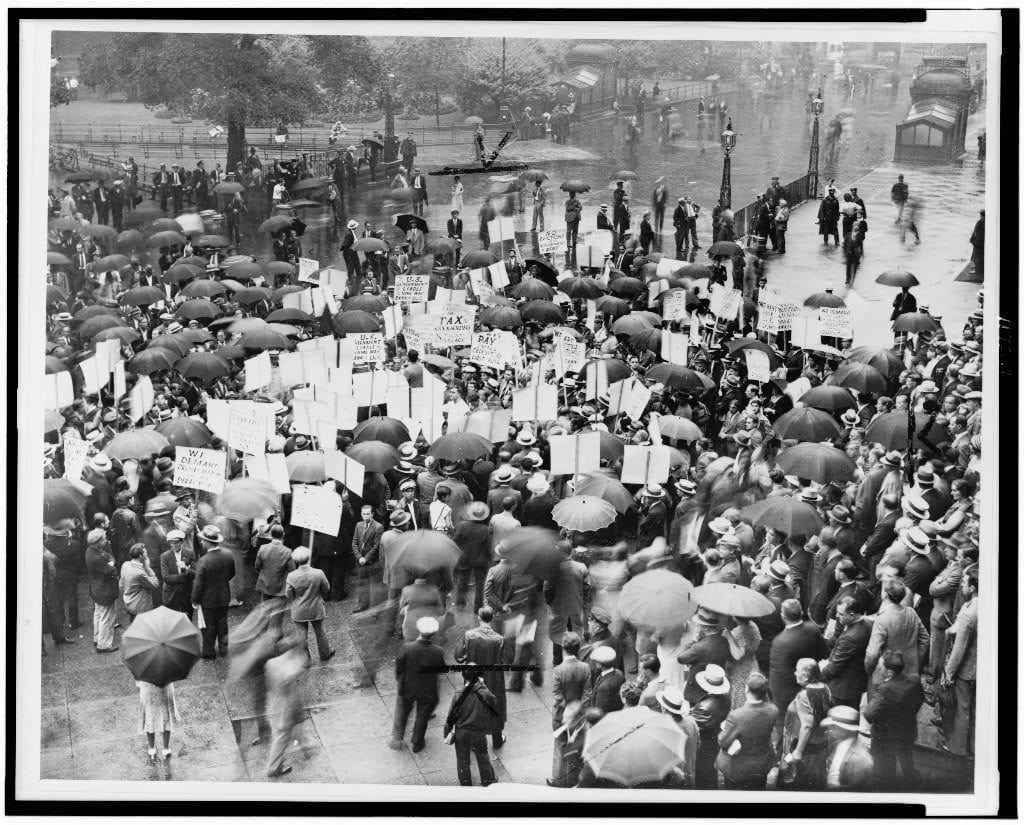

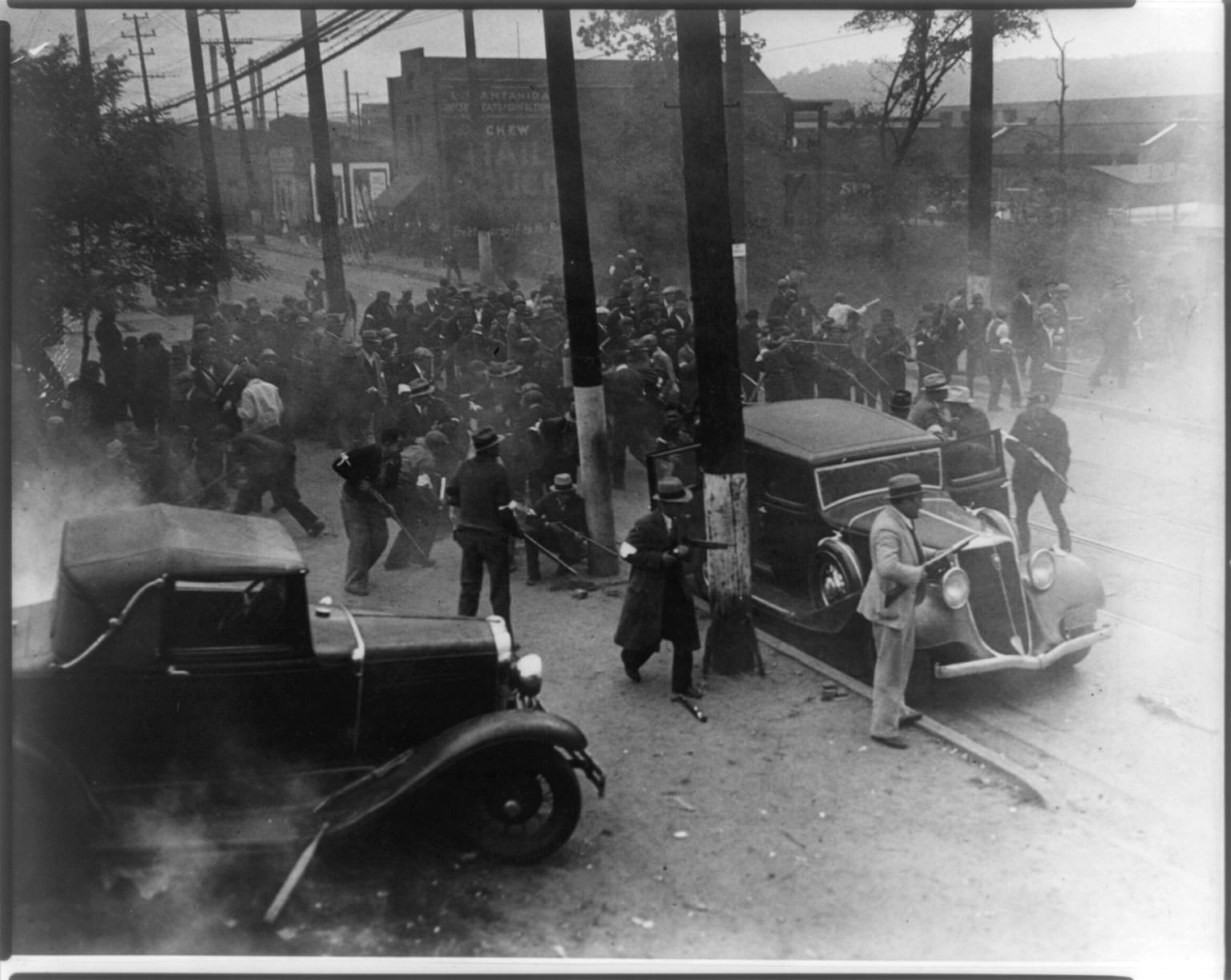

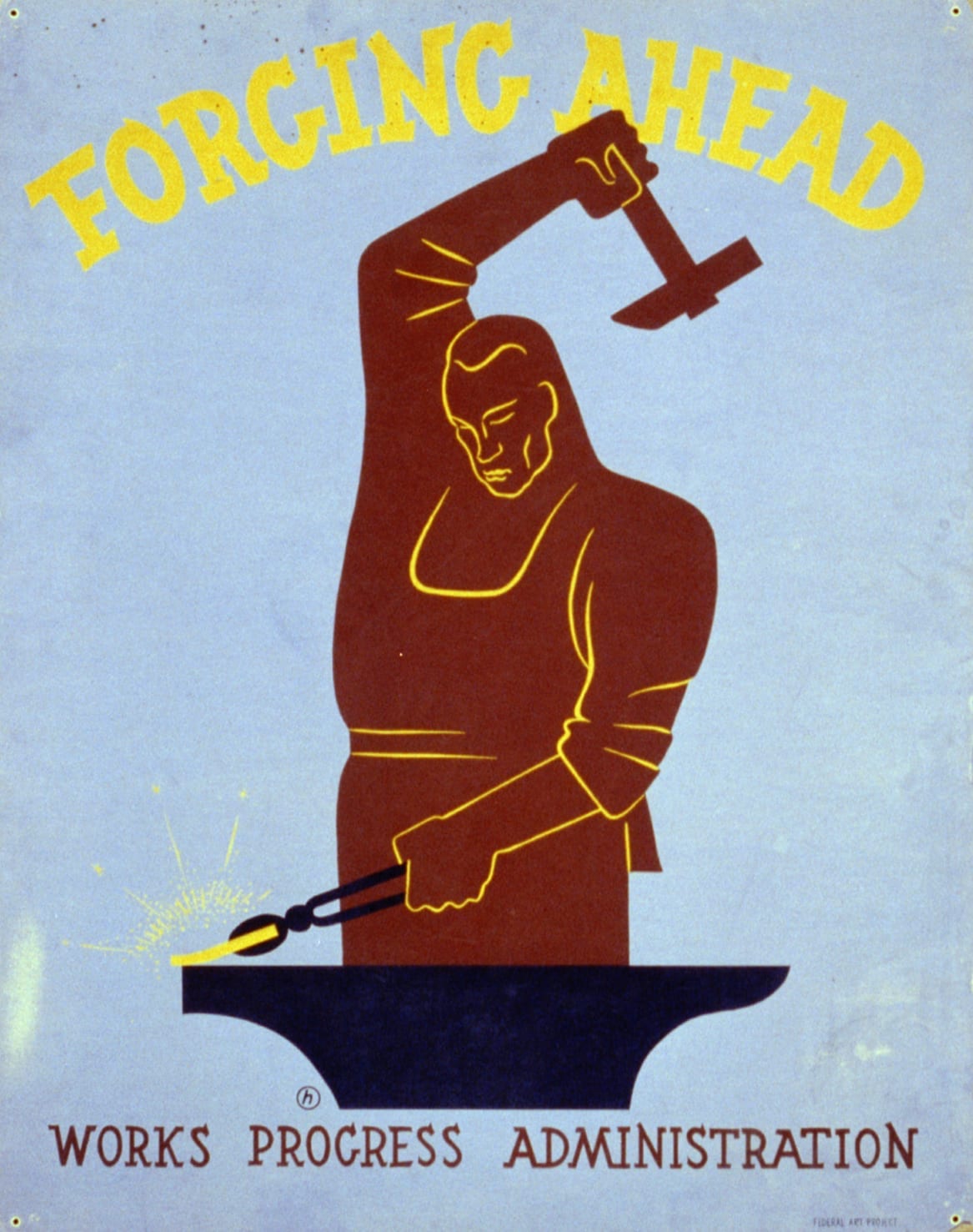

In 1935, Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act), which declared that employees have the right to form or join unions and “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) was created to enforce the Wagner Act. After passage of the Act, Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation fired ten workers for trying to promote unionization in its huge steel plant in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. The NLRB found that Jones & Laughlin had violated the Wagner Act and ordered the company “to cease and desist from such discrimination and coercion, to offer reinstatement to ten of the employees named, to make good their losses in pay, and to post for thirty days notice that the corporation would not discharge or discriminate against members, or those desiring to become members, of the labor union.” The corporation failed to comply, so NLRB petitioned the US Court of Appeals to enforce the order. But the Circuit Court denied NLRB’s request based on precedents like EC Knight (1895), Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), Schecter Poultry (1935), and Carter Coal (1936), which the Court interpreted to mean that the federal government’s interstate commerce power did not give it the authority to regulate local manufacturing. NLRB then appealed to the Supreme Court.

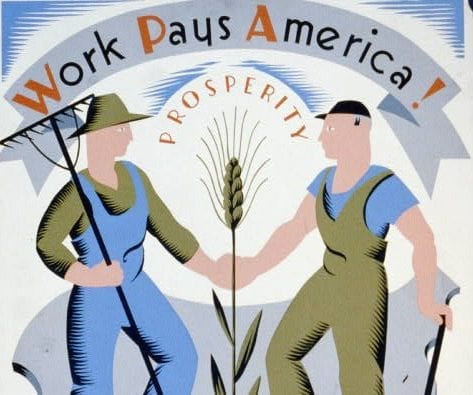

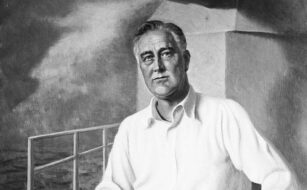

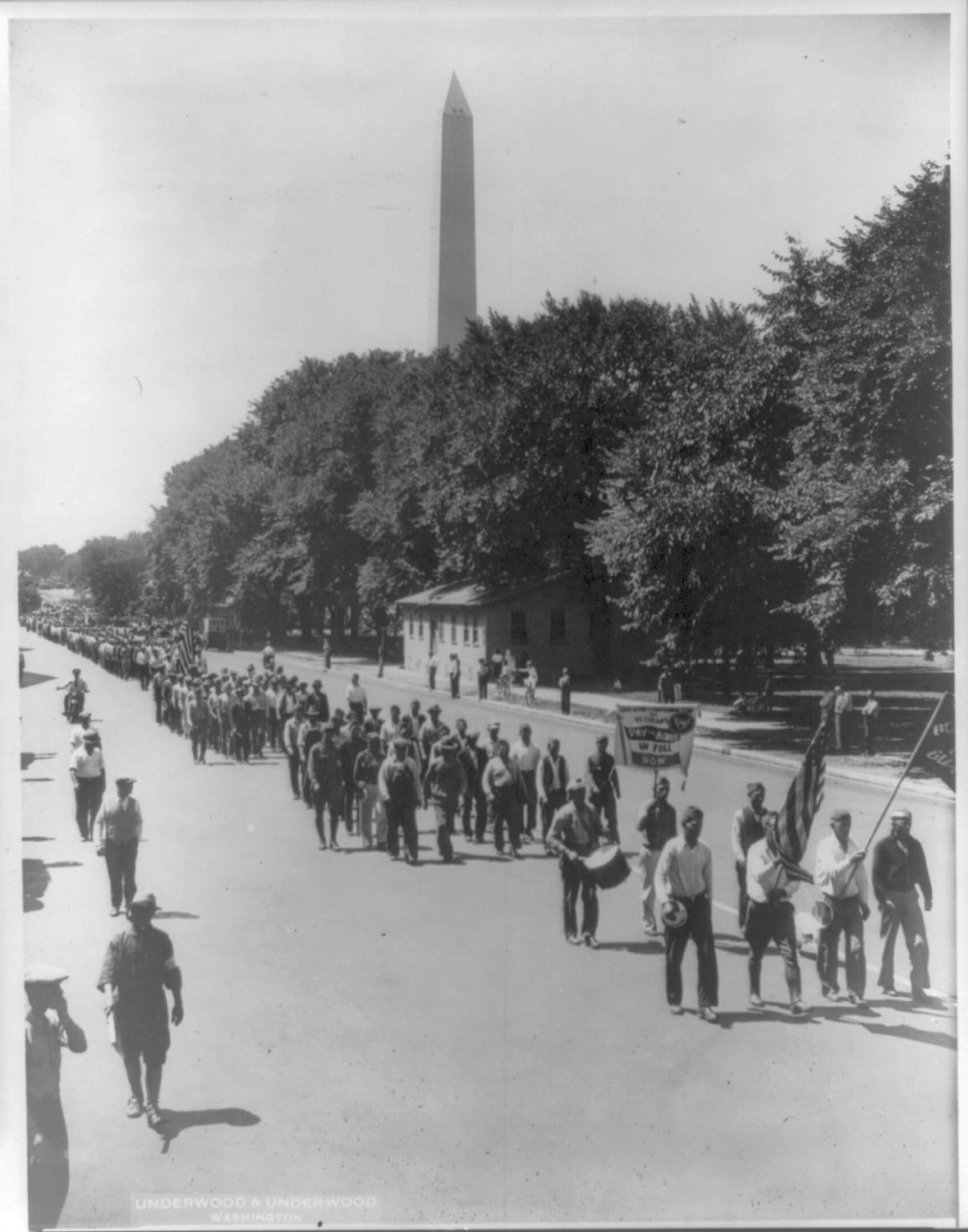

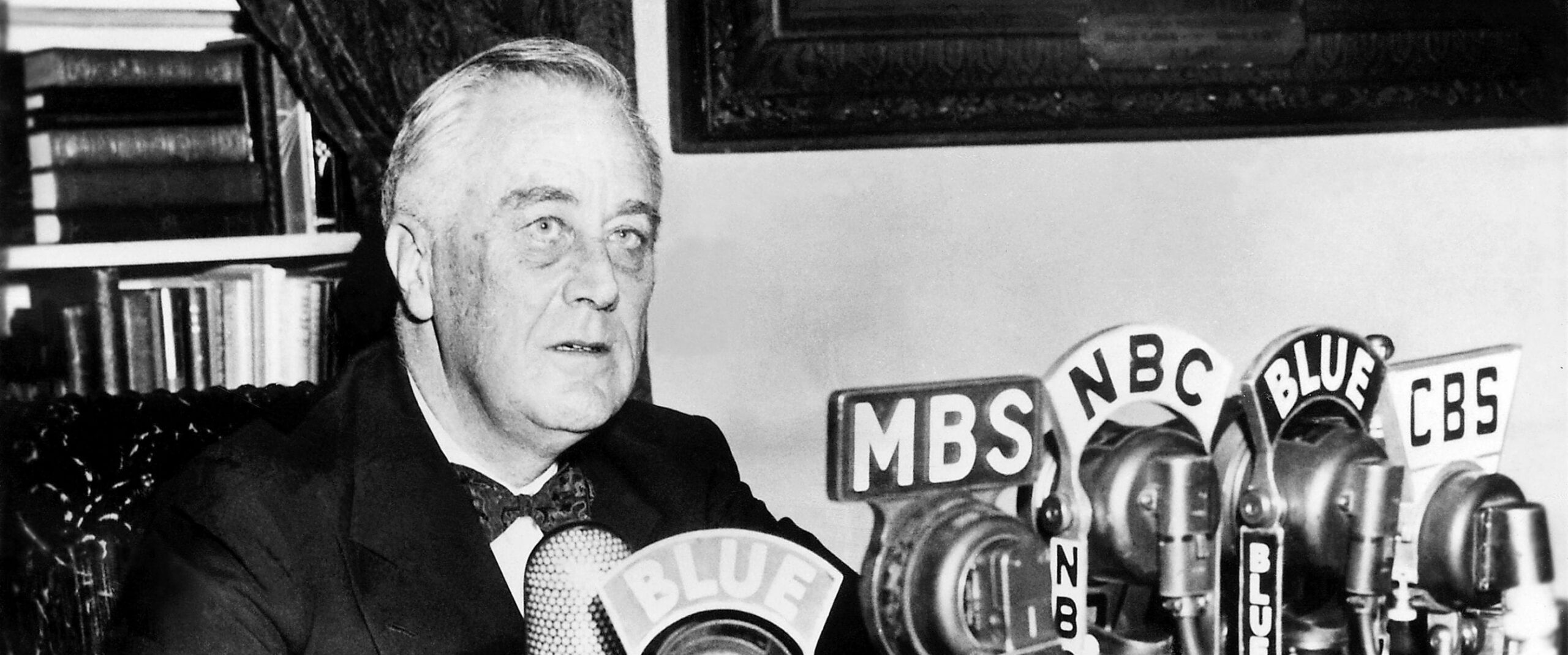

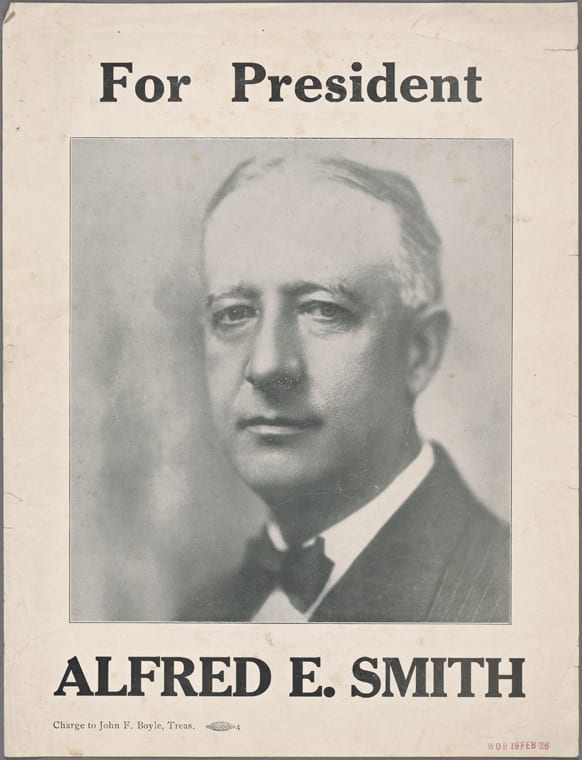

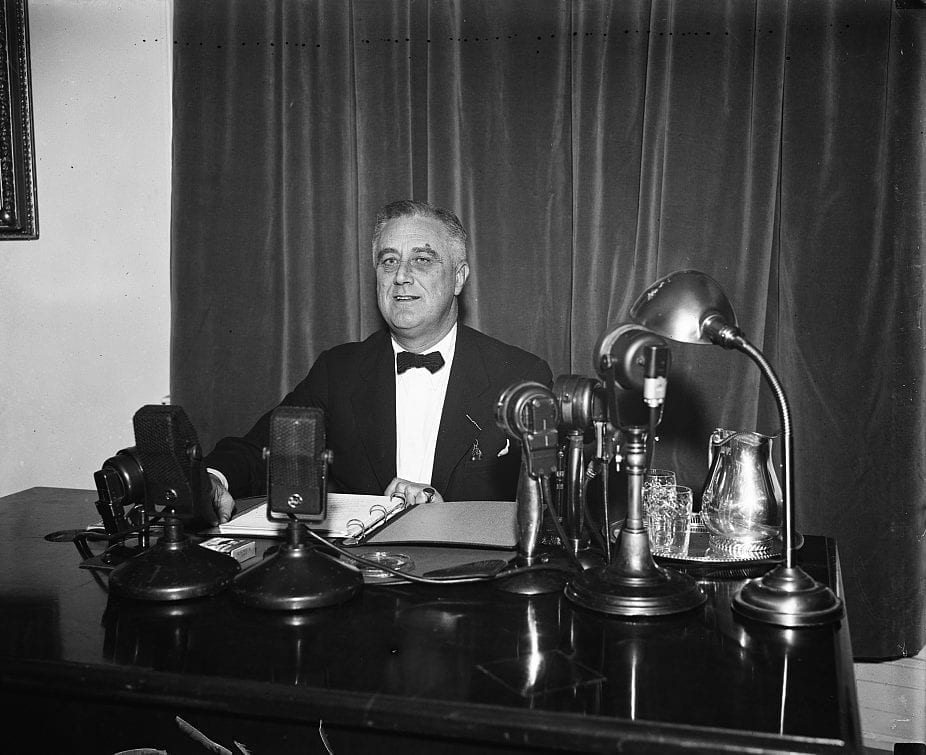

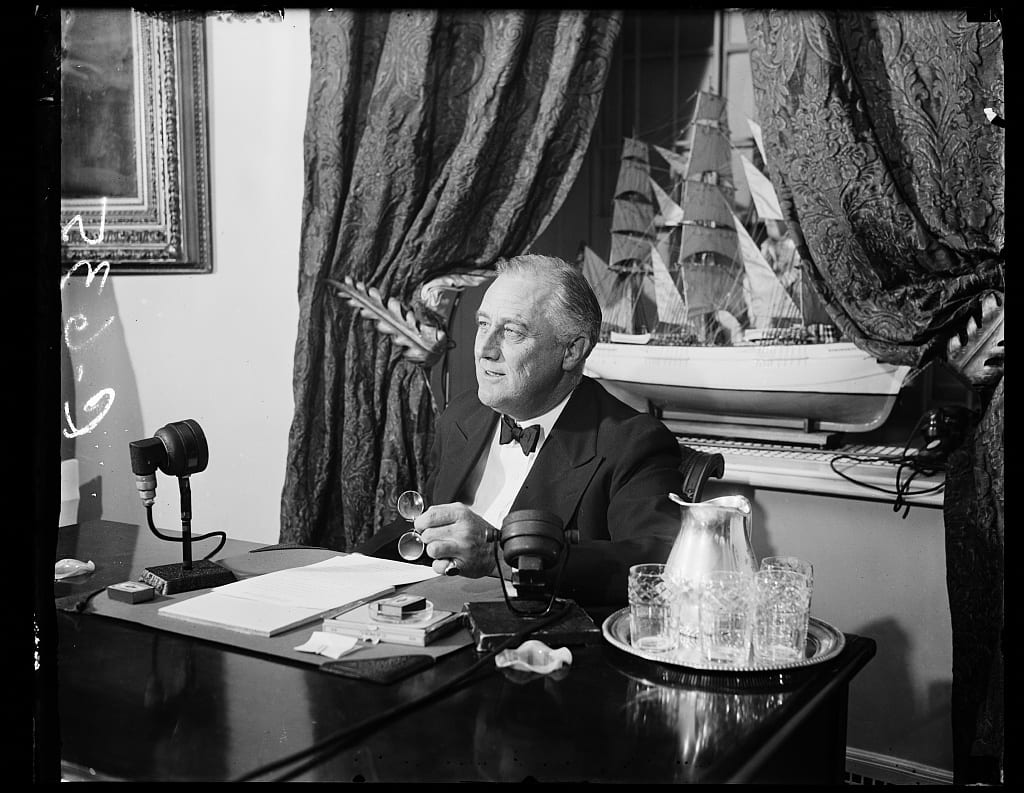

The Court heard oral arguments in the case on February 10 and11, 1937. Frustrated by the Supreme Court striking down New Deal legislation, President Franklin D. Roosevelt went on national radio on March 9 to deliver a “fireside chat” on his plan to reorganize the federal judiciary, particularly by adding one member to the Supreme Court for every member over seventy years old. This “court packing” scheme caused a national controversy, with critics arguing that it was an attack on the independence of the judiciary. A little over a month later, the Court handed down its rulings in Jones & Laughlin and West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, both of which were 5-4 decisions that overruled previous cases and upheld the power of state and federal governments to regulate labor conditions in local businesses. Together, these decisions were called “the switch in time that saved nine” because they helped to take much of the momentum out of FDR’s plan to change the Court, although the President continued unsuccessfully to push the plan into the 1938 election season. Jones & Laughlin served as a precedent for the expansion of Congress’s commerce power confirmed by FDR-appointed majorities in US v. Darby (1941) and Wickard v. Filburn (1942), an expansion that went largely unchecked by the Supreme Court for over fifty years (until US v. Lopez in 1995).

Source: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/301/58/

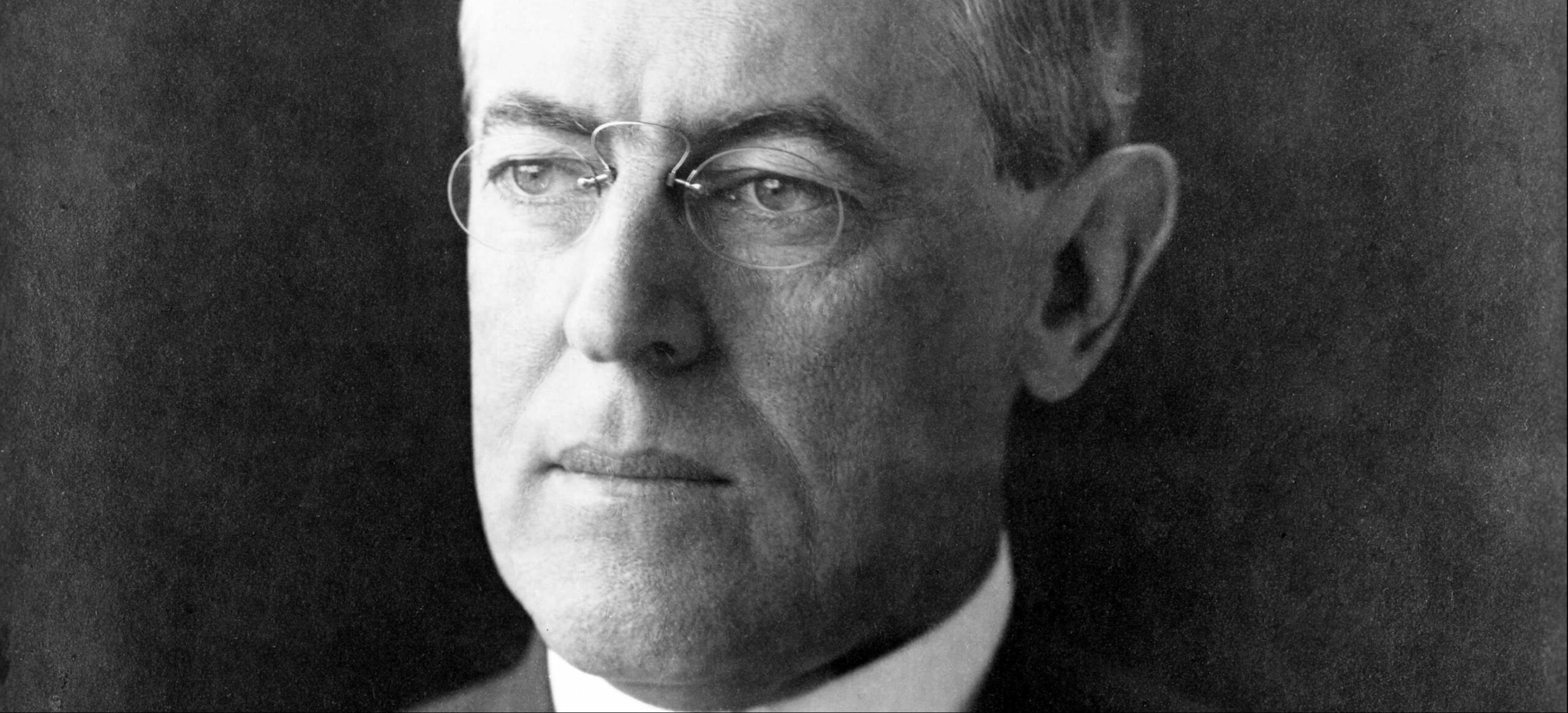

Chief Justice HUGHES delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by Justices BRANDEIS, STONE, ROBERTS, and CARDOZO.

. . . Jones & Laughlin . . . is organized under the laws of Pennsylvania and has its principal office at Pittsburgh. It is engaged in the business of manufacturing iron and steel in plants situated in Pittsburgh and nearby Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. It manufactures and distributes a widely diversified line of steel and pig iron, being the fourth largest producer of steel in the United States. With its subsidiaries—nineteen in number—it is a completely integrated enterprise, owning and operating ore, coal and limestone properties, lake and river transportation facilities, and terminal railroads located at its manufacturing plants. . . . [It] has about 10,000 employees in its Aliquippa plant, which is located in a community of about 30,000 persons. . . .

. . . We turn to the questions of law which [Jones & Laughlin] urges in contesting the validity and application of the act.

First. The scope of the Act.—The Act is challenged in its entirety as an attempt to regulate all industry, thus invading the reserved powers of the States over their local concerns. It is asserted that . . . the Act is not a true regulation of such commerce or of matters which directly affect it, but, on the contrary, has the fundamental object of placing under the compulsory supervision of the federal government all industrial labor relations within the nation. . . .

If this conception of terms, intent, and consequent inseparability were sound, the Act would necessarily fall by reason of the limitation upon the federal power which inheres in the constitutional grant, as well as because of the explicit reservation of the Tenth Amendment. The authority of the federal government may not be pushed to such an extreme as to destroy the distinction, which the commerce clause itself establishes, between commerce “among the several States” and the internal concerns of a State. That distinction between what is national and what is local in the activities of commerce is vital to the maintenance of our federal system. . . .

[But e think it clear that the National Labor Relations Act may be construed so as to operate within the sphere of constitutional authority. . . .

. . . The grant of authority to the Board does not purport to extend to the relationship between all industrial employees and employers. Its terms do not impose collective bargaining upon all industry regardless of effects upon interstate or foreign commerce. It purports to reach only what may be deemed to burden or obstruct that commerce, and, thus qualified, it must be construed as contemplating the exercise of control within constitutional bounds. It is a familiar principle that acts which directly burden or obstruct interstate or foreign commerce, or its free flow, are within the reach of the congressional power. . . . It is the effect upon commerce, not the source of the injury, which is the criterion. . . . Whether or not particular action does affect commerce in such a close and intimate fashion as to be subject to federal control, and hence to lie within the authority conferred upon the Board, is left by the statute to be determined as individual cases arise. We are thus to inquire whether, in the instant case, the constitutional boundary has been passed.

Second. The fair labor practices in question. . . .

. . . [I]n its present application, the statute goes no further than to safeguard the right of employees to self-organization and to select representatives of their own choosing for collective bargaining or other mutual protection without restraint or coercion by their employer.

That is a fundamental right. Employees have as clear a right to organize and select their representatives for lawful purposes as the respondent has to organize its business and select its own officers and agents. Discrimination and coercion to prevent the free exercise of the right of employees to self-organization and representation is a proper subject for condemnation by competent legislative authority. . . . Congress was not required to ignore this right, but could safeguard it. Congress could seek to make appropriate collective action of employees an instrument of peace, rather than of strife. We said that such collective action would be a mockery if representation were made futile by interference with freedom of choice. Hence the prohibition by Congress of interference with the selection of representatives for the purpose of negotiation and conference between employers and employees, “instead of being an invasion of the constitutional right of either, was based on the recognition of the rights of both.”[1]

[2]Third. The application of the Act to employees engaged in production.—The principle involved.—

[Jones & Laughlin] says that whatever may be said of employees engaged in interstate commerce, the industrial relations and activities in the manufacturing department of [its] enterprise are not subject to federal regulation. The argument rests upon the proposition that manufacturing, in itself, is not commerce. . . .

. . . The congressional authority to protect interstate commerce from burdens and obstructions is not limited to transactions which can be deemed to be an essential part of a “flow” of interstate or foreign commerce. Burdens and obstructions may be due to injurious action springing from other sources. The fundamental principle is that the power to regulate commerce is the power to enact “all appropriate legislation” for its “protection or advancement”; . . . to adopt measures “to promote its growth and insure its safety”; . . . “to foster, protect, control, and restrain.” . . . That power is plenary, and may be exerted to protect interstate commerce “no matter what the source of the dangers which threaten it.”[3] Although activities may be intrastate in character when separately considered, if they have such a close and substantial relation to interstate commerce that their control is essential or appropriate to protect that commerce from burdens and obstructions, Congress cannot be denied the power to exercise that control. . . . Undoubtedly the scope of this power must be considered in the light of our dual system of government and may not be extended so as to embrace effects upon interstate commerce so indirect and remote that to embrace them, in view of our complex society, would effectually obliterate the distinction between what is national and what is local and create a completely centralized government. The question is necessarily one of degree. . . .

Fourth. Effects of the unfair labor practice in [Jones & Laughlin’s] enterprise.— Giving full weight to [Jones & Laughlin’s] contention with respect to a break in the complete continuity of the “stream of commerce” by reason of respondent’s manufacturing operations, the fact remains that the stoppage of those operations by industrial strife would have a most serious effect upon interstate commerce. In view of respondent’s far-flung activities, it is idle to say that the effect would be indirect or remote. It is obvious that it would be immediate and might be catastrophic. We are asked to shut our eyes to the plainest facts of our national life, and to deal with the question of direct and indirect effects in an intellectual vacuum. Because there may be but indirect and remote effects upon interstate commerce in connection with a host of local enterprises throughout the country, it does not follow that other industrial activities do not have such a close and intimate relation to interstate commerce as to make the presence of industrial strife a matter of the most urgent national concern. When industries organize themselves on a national scale, making their relation to interstate commerce the dominant factor in their activities, how can it be maintained that their industrial labor relations constitute a forbidden field into which Congress may not enter when it is necessary to protect interstate commerce from the paralyzing consequences of industrial war? We have often said that interstate commerce itself is a practical conception. It is equally true that interferences with that commerce must be appraised by a judgment that does not ignore actual experience.

Experience has abundantly demonstrated that the recognition of the right of employees to self-organization and to have representatives of their own choosing for the purpose of collective bargaining is often an essential condition of industrial peace. . . . And of what avail is it to protect the facility of transportation if interstate commerce is throttled with respect to the commodities to be transported! . . .

. . . Instead of being beyond the pale, we think that it presents in a most striking way the close and intimate relation which a manufacturing industry may have to interstate commerce, and we have no doubt that Congress had constitutional authority to safeguard the right of respondent’s employees to self-organization and freedom in the choice of representatives for collective bargaining. . . .

Our conclusion is that the order of the Board was within its competency, and that the Act is valid as here applied. The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reversed, and the cause is remanded for further proceedings in conformity with this opinion. It is so ordered.

Reversed

Justice McREYNOLDS dissenting, joined by Justices VAN DEVANTER, SUTHERLAND and BUTLER.

. . . Considering the far-reaching import of these decisions, the departure from what we understand has been consistently ruled here, and the extraordinary power confirmed to a Board of three, the obligation to present our views becomes plain.

The Court, as we think, departs from well established principles followed in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), and Carter v. Carter Coal Co. (1936), . . . [which] have held the power of Congress under the commerce clause does not extend to relations between employers and their employees engaged in manufacture, and therefore the Act conferred upon the National Labor Relations Board no authority in respect of matters covered by the questioned orders. . . .

By its terms, the Labor Act extends to employers, large and small, unless excluded by definition, and declares that if one of these interferes with, restrains, or coerces any employee regarding his labor affiliations, etc., this shall be regarded as unfair labor practice. And a “labor organization” means any organization of any kind or any agency or employee representation committee or plan which exists for the purpose in whole or in part of dealing with employers concerning grievances, labor disputes, wages, rates of pay, hours of employment, or conditions of work. . . .

Any effect on interstate commerce by the discharge of employees shown here would be indirect and remote in the highest degree, as consideration of the facts will show. . . . [T]en men out of ten thousand were discharged. . . . The immediate effect in the factor may be to create discontent among all those employed, and a strike may follow which, in turn, may result in reducing production, which ultimately may reduce the volume of goods moving in interstate commerce. By this chain of indirect and progressively remote events, we finally reach the evil with which it is said the legislation under consideration undertakes to deal. A more remote and indirect interference with interstate commerce or a more definite invasion of the powers reserved to the states is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine.

The Constitution still recognizes the existence of states with indestructible powers; the Tenth Amendment was supposed to put them beyond controversy.

We are told that Congress may protect the “stream of commerce,” and that one who buys raw material without the state, manufactures it therein, and ships the output to another state is in that stream. Therefore it is said he may be prevented from doing anything which may interfere with its flow.

This, too, goes beyond the constitutional limitations heretofore enforced. If a man raises cattle and regularly delivers them to a carrier for interstate shipment, may Congress prescribe the conditions under which he may employ or discharge helpers on the ranch? The products of a mine pass daily into interstate commerce; many things are brought to it from other states. Are the owners and the miners within the power of Congress in respect of the latter’s tenure and discharge? May a mill owner be prohibited from closing his factory or discontinuing his business because so to do would stop the flow of products to and from his plant in interstate commerce?

May employees in a factory be restrained from quitting work in a body because this will close the factory and thereby stop the flow of commerce? May arson of a factory be made a federal offense whenever this would interfere with such flow? If the business cannot continue with the existing wage scale, may Congress command a reduction? If the ruling of the Court just announced is adhered to, these questions suggest some of the problems certain to arise.

And if this theory of a continuous “stream of commerce” as now defined is correct, will it become the duty of the federal government hereafter to suppress every strike which by possibility it may cause a blockade in that stream? Moreover, since Congress has intervened, are labor relations between most manufacturers and their employees removed from all control by the state? . . .

There is no ground on which reasonably to hold that refusal by a manufacturer, whose raw materials come from states other than that of his factory and whose products are regularly carried to other states, to bargain collectively with employees in his manufacturing plant directly affects interstate commerce. In such business, there is not one, but two, distinct movements or streams in interstate transportation. The first brings in raw material, and there ends. Then follows manufacture, a separate and local activity. Upon completion of this, and not before, the second distinct movement or stream in interstate commerce begins, and the products go to other states. Such is the common course for small as well as large industries. It is unreasonable and unprecedented to say the commerce clause confers upon Congress power to govern relations between employers and employees in these local activities. . . .

That Congress has power by appropriate means, not prohibited by the Constitution, to prevent direct and material interference with the conduct of interstate commerce is settled doctrine. But the interference struck at must be direct and material, not some mere possibility contingent on wholly uncertain events, and there must be no impairment of rights guaranteed. . . .

“Neutrality Act”of May 1, 1937

May 01, 1937

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.