No related resources

Introduction

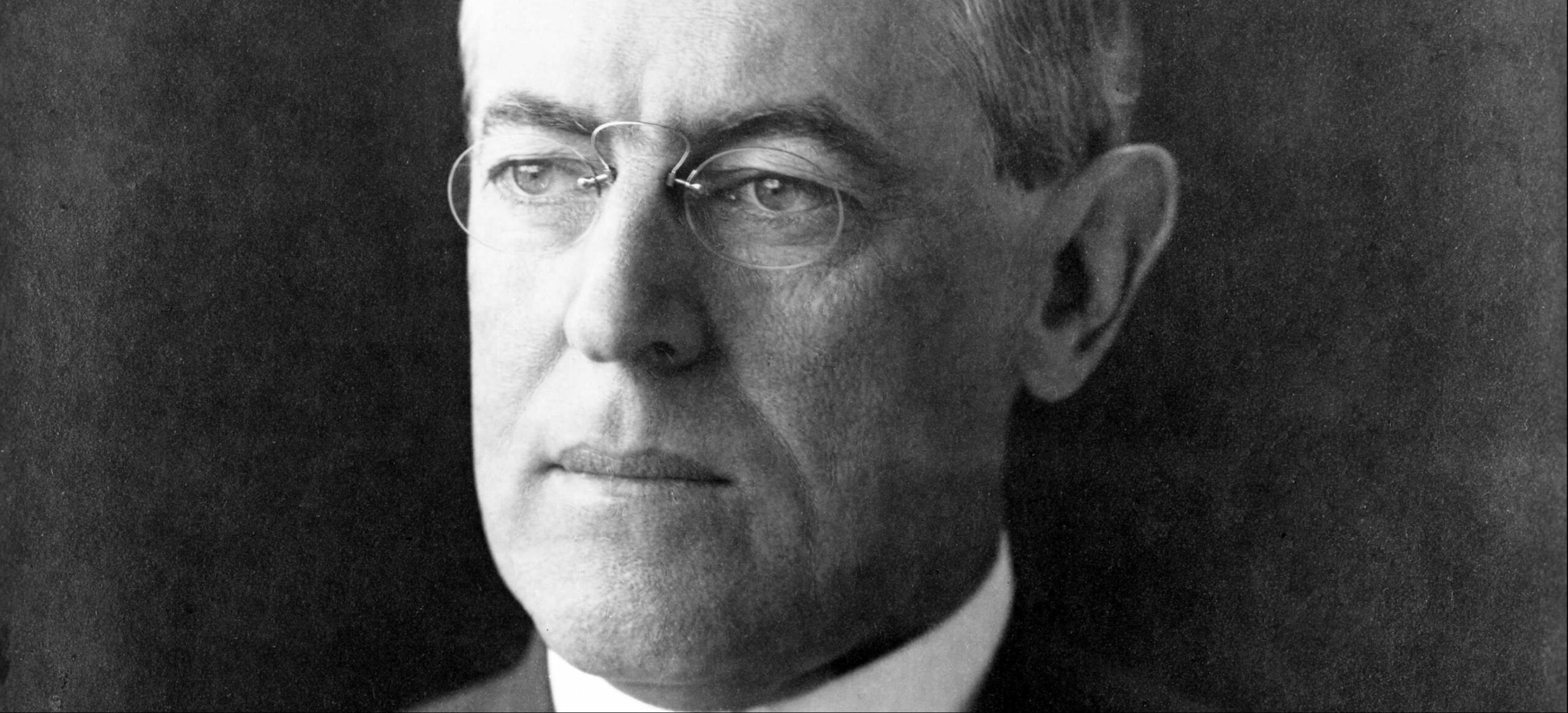

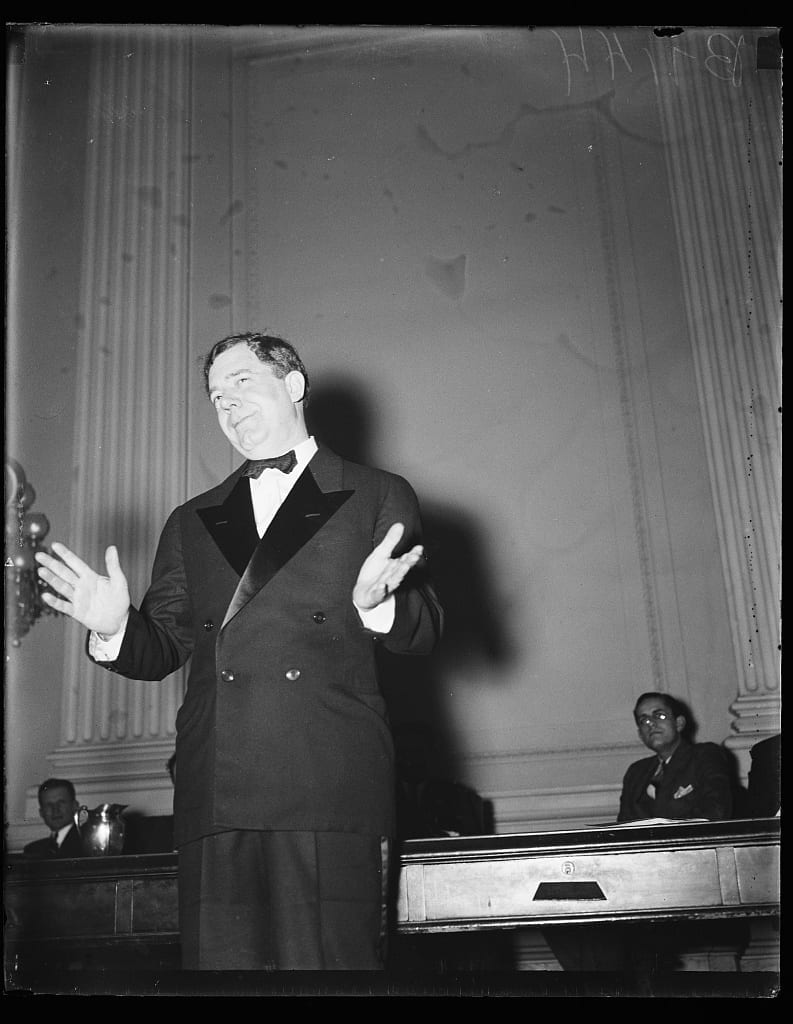

Having witnessed a large portion of his New Deal program gutted by adverse Supreme Court decisions (See A. L. A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States and Humphrey’s Executor v. United States), Franklin Roosevelt (1882–1945) launched a bold attack on the Court. In 1937 he proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Act as a means to enlarge the Court and dilute the conservatives’ votes. The proposal, popularly known as “the president’s Court-packing plan,” would allow the president to appoint a new associate justice for every justice on the federal bench over the age of seventy. Had the bill passed, Roosevelt would have been able to appoint no fewer than six new justices to the Supreme Court. The proposal was met by general outrage, and the bill turned out to be a political liability for Roosevelt and was never adopted by Congress.

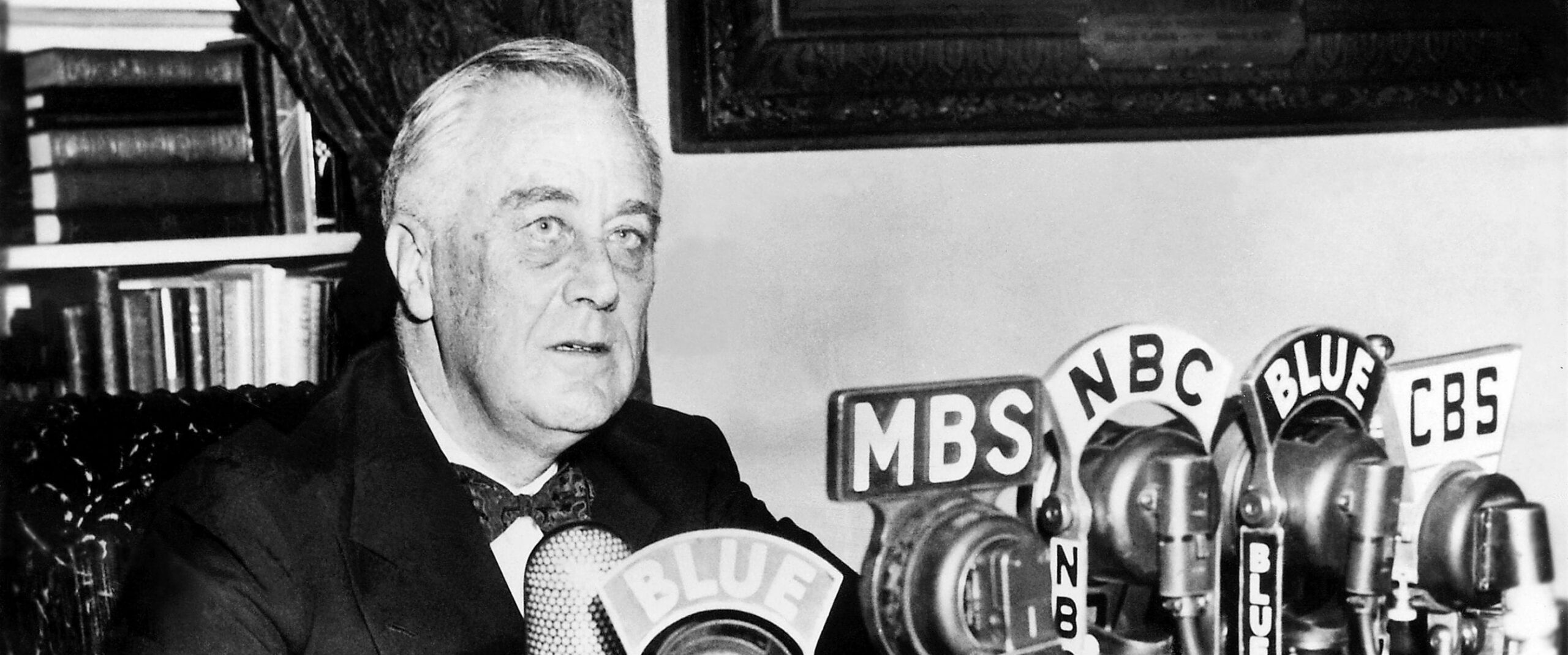

Hoping to gain public support for his plan, Roosevelt addressed the nation in one of his “fireside chats.” In his radio broadcast Roosevelt compared the three branches of government to a three-horse team that together plowed the field for the people. While Congress and the president were pulling their weight, the judiciary was not. The analogy is jarring in its contrast to the traditional separation-of-powers view. While the branches are expected to work together, they are also designed to check one another in order to protect the powers of one branch from being usurped by the others. Roosevelt argued that rather than an attempt to improperly influence the Court, the Judicial Reorganization Act was meant to restore the integrity of the Court. The Court’s true purpose, the president said, was to uphold a Constitution that gives the federal government broad and ample power to meet the needs of the time. However, a conservative bloc on the Court (known as the “Four Horsemen”) had perverted that original purpose of the Court. The nature of the proposed reform implied that the Four Horsemen had lost touch with the needs of the day, something that could only be corrected by the addition of new and younger justices.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat,” March 9, 1937, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15381.

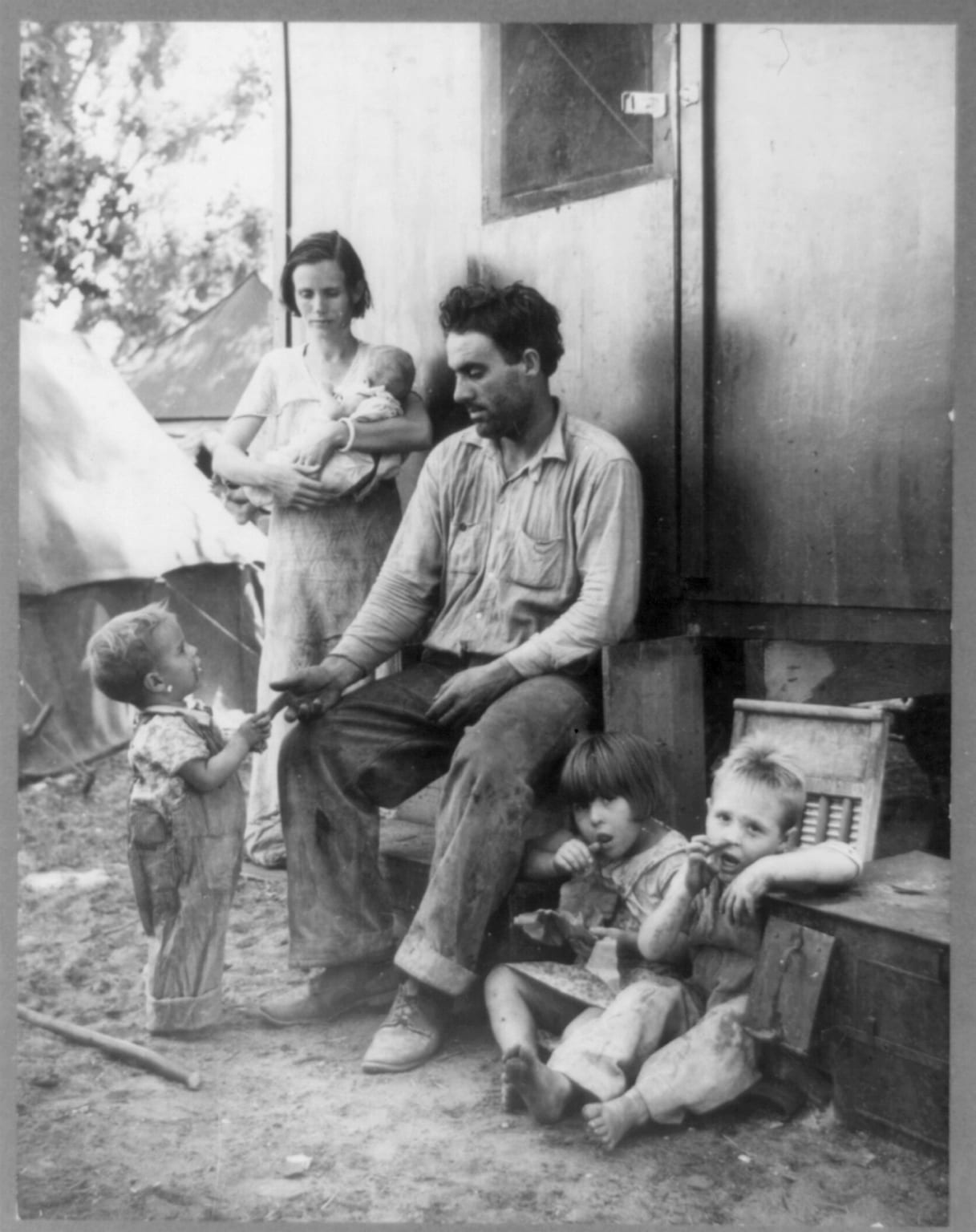

. . .I want to talk with you very simply about the need for present action in this crisis—the need to meet the unanswered challenge of one-third of a nation ill-nourished, ill-clad, ill-housed.

Last Thursday, I described the American form of government as a three-horse team provided by the Constitution to the American people so that their field might be plowed.1 The three horses are, of course, the three branches of government—the Congress, the executive, and the courts. Two of the horses are pulling in unison today; the third is not. Those who have intimated that the president of the United States is trying to drive that team, overlook the simple fact that the president, as chief executive, is himself one of the three horses.

It is the American people themselves who are in the driver’s seat. It is the American people themselves who want the furrow plowed.

It is the American people themselves who expect the third horse to pull in unison with the other two.

I hope that you have re-read the Constitution of the United States in these past few weeks. Like the Bible, it ought to be read again and again.

It is an easy document to understand when you remember that it was called into being because the Articles of Confederation under which the original thirteen states tried to operate after the Revolution showed the need of a national government with power enough to handle national problems. In its Preamble, the Constitution states that it was intended to form a more perfect union and promote the general welfare; and the powers given to the Congress to carry out those purposes can be best described by saying that they were all the powers needed to meet each and every problem which then had a national character and which could not be met by merely local action.

But the framers went further. Having in mind that in succeeding generations many other problems then undreamed of would become national problems, they gave to the Congress the ample broad powers “to levy taxes. . . and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.”

That, my friends, is what I honestly believe to have been the clear and underlying purpose of the patriots who wrote a federal Constitution to create a national government with national power, intended as they said, “to form a more perfect union for ourselves and our posterity.”

For nearly twenty years there was no conflict between the Congress and the Court. . . . But since the rise of the modern movement for social and economic progress through legislation, the Court has more and more often and more and more boldly asserted a power to veto laws passed by the Congress and state legislatures in complete disregard of this original limitation.

In the last four years the sound rule of giving statutes the benefit of all reasonable doubt has been cast aside. The Court has been acting not as a judicial body, but as a policymaking body.

When the Congress has sought to stabilize national agriculture, to improve the conditions of labor, to safeguard business against unfair competition, to protect our national resources, and in many other ways to serve our clearly national needs, the majority of the Court has been assuming the power to pass on the wisdom of these acts of the Congress—and to approve or disapprove the public policy written into these laws.2…

The Court in addition to the proper use of its judicial functions has improperly set itself up as a third House of the Congress—a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it—reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there.

We have, therefore, reached the point as a nation where we must take action to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself. We must find a way to take an appeal from the Supreme Court to the Constitution itself. We want a Supreme Court which will do justice under the Constitution—not over it. In our Courts we want a government of laws and not of men.

I want—as all Americans want—an independent judiciary as proposed by the framers of the Constitution. That means a Supreme Court that will enforce the Constitution as written—that will refuse to amend the Constitution by the arbitrary exercise of judicial power—amendment by judicial say-so. It does not mean a judiciary so independent that it can deny the existence of facts universally recognized. . . .

What is my proposal? It is simply this: whenever a judge or justice of any federal court has reached the age of seventy and does not avail himself of the opportunity to retire on a pension, a new member shall be appointed by the president then in office, with the approval, as required by the Constitution, of the Senate of the United States.

That plan has two chief purposes. By bringing into the judicial system a steady and continuing stream of new and younger blood, I hope, first, to make the administration of all federal justice speedier and, therefore, less costly; secondly, to bring to the decision of social and economic problems younger men who have had personal experience and contact with modern facts and circumstances under which average men have to live and work. This plan will save our national Constitution from hardening of the judicial arteries. . . .

This plan of mine is no attack on the Court; it seeks to restore the Court to its rightful and historic place in our system of constitutional government and to have it resume its high task of building anew on the Constitution “a system of living law.” The Court itself can best undo what the Court has done. . . .

During the past half century the balance of power between the three great branches of the federal government has been tipped out of balance by the Courts in direct contradiction of the high purposes of the framers of the Constitution. It is my purpose to restore that balance. You who know me will accept my solemn assurance that in a world in which democracy is under attack, I seek to make American democracy succeed. You and I will do our part.

- 1. Address at the Democratic Victory Dinner, Washington, DC, March 4, 1937.

- 2. The Court struck down numerous pieces of New Deal legislation between 1935 and 1937, most importantly the National Industrial Recovery Act (designed to bring widespread relief to the nation’s ailing industrial economy) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 (designed to help farmers and restore agricultural commodities’ prices). In 1935, Congress declared that the NIRA violated both the nondelegation doctrine and the commerce clause in Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States. In January 1936, the Court decided that the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 violated the taxing and spending clause in the case of United States v. Butler.

Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization

March 29, 1937

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.