No related resources

Introduction

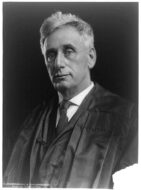

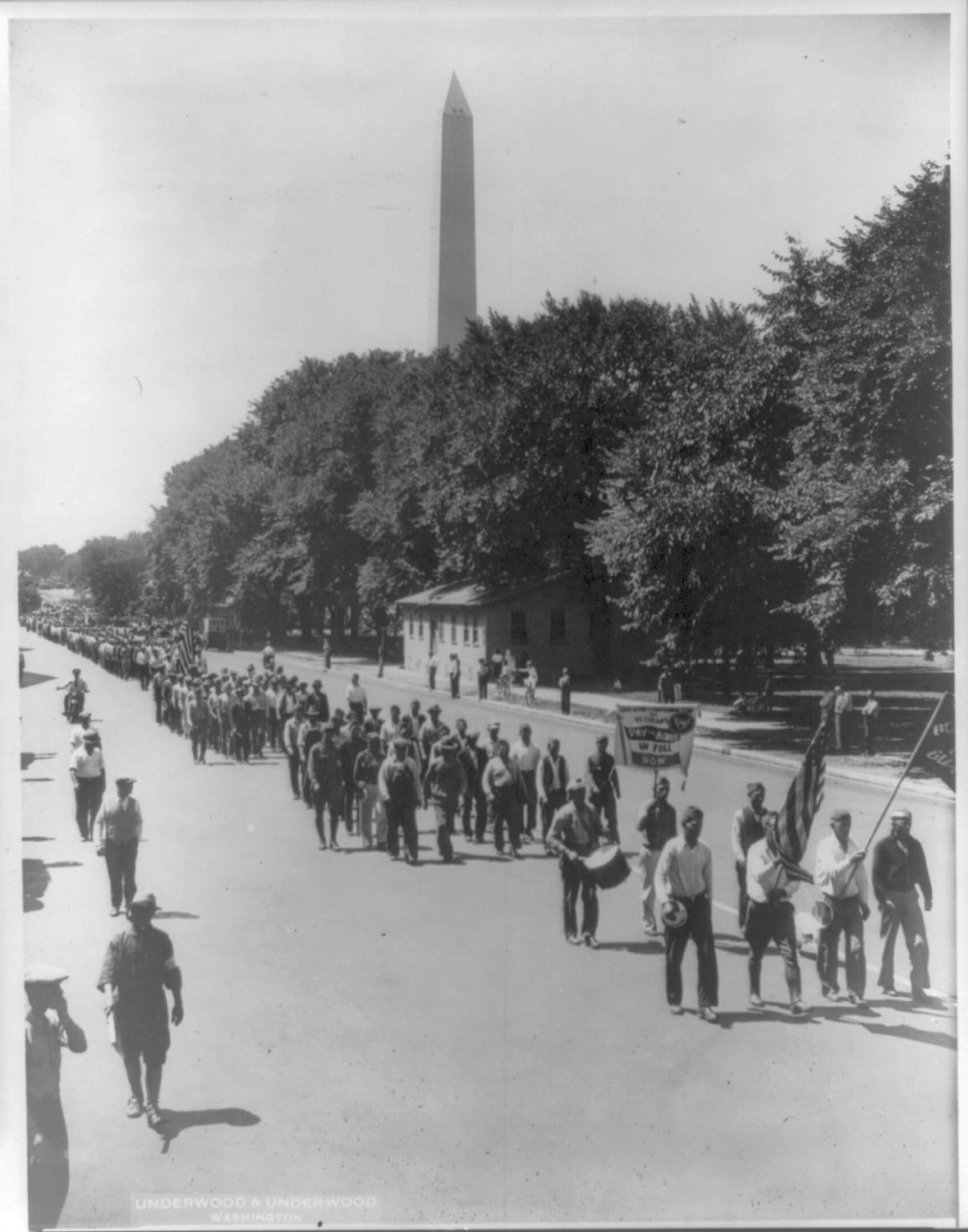

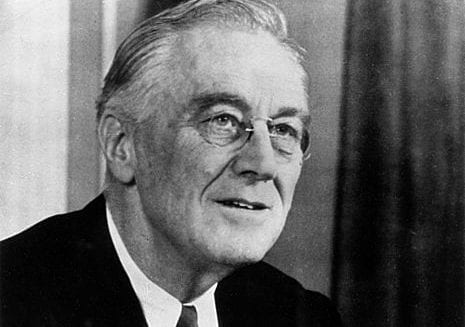

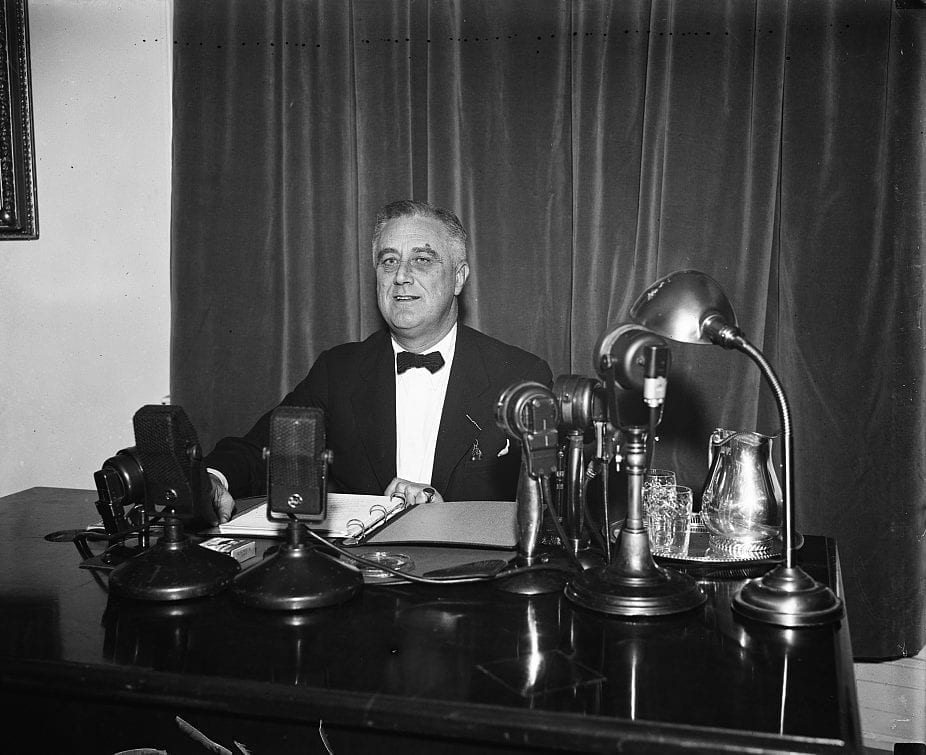

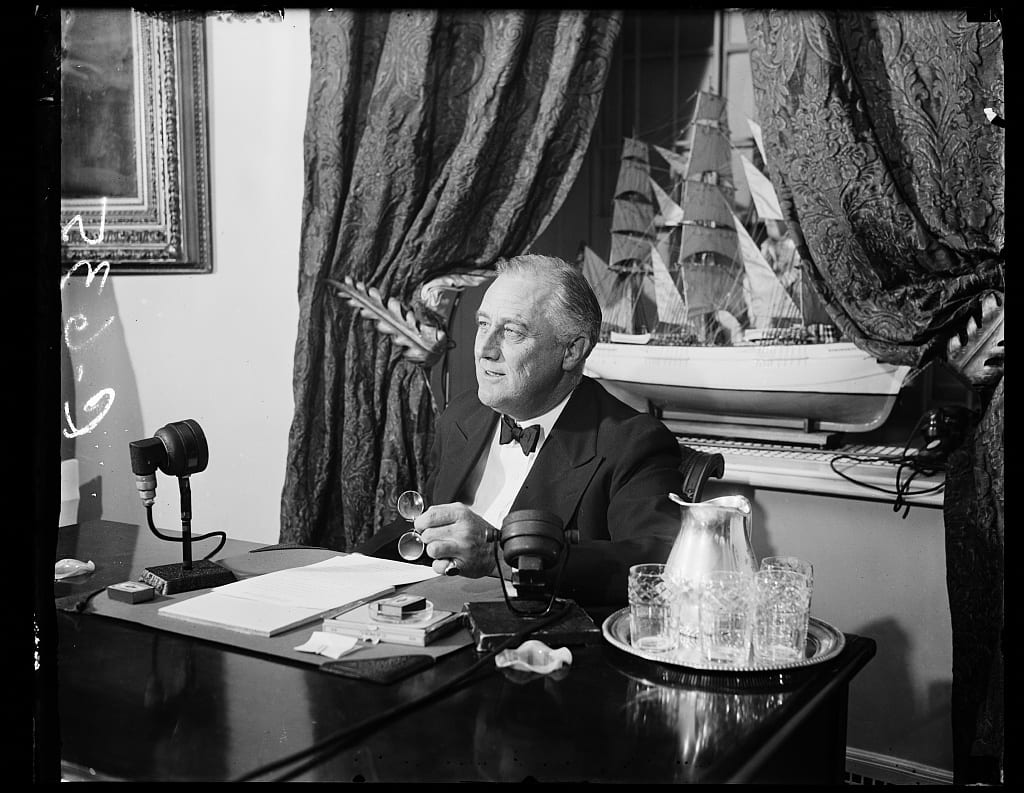

In 1934, Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the president to prohibit the sale of arms by American companies to Bolivia and Paraguay because the two nations were engaged in ongoing and brutal war. Franklin Roosevelt quickly issued a proclamation to that effect. The American arms manufacturer Curtiss-Wright violated Roosevelt’s order, and, in its defense, the company’s attorneys argued that the joint resolution was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the president. In this, they were relying on a legal theory going back to John Locke that the legislative and executive powers of a government had to be not only placed but maintained in distinct hands. This theory had also provided the undergirding for many of the Supreme Court’s arguments in striking down key New Deal provisions between 1935 and 1937. Instead of ruling against the president, however, a seven-to-one majority upheld the proclamation. In what follows, Justice Sutherland makes an argument that has turned out to be the high-water mark for executive power in foreign affairs. Along with Alexander Hamilton’s argument defending President George Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation (Helvidius-Pacificus Debate (1793)), Sutherland’s opinion is frequently cited by those arguing for presidential control over war and peace (Memorandum on the President’s Constitutional Authority to Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them (2001)).

Source: United States Reports. Volume 299, Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court at October Term, 1936 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937), 311–33.

Mr. Justice Sutherland delivered the opinion of the Court.

On January 27, 1936, an indictment was returned in the court below, the first count of which charges that appellees, beginning with the 29th day of May, 1934, conspired to sell in the United States certain arms of war, namely fifteen machine guns, to Bolivia, a country then engaged in armed conflict in the Chaco, in violation of the Joint Resolution of Congress approved May 28, 1934, and the provisions of a proclamation issued on the same day by the President of the United States pursuant to authority conferred by §1 of the resolution. . . .

The determination which we are called to make, therefore, is whether the Joint Resolution, as applied to the situation, is vulnerable to attack under the rule that forbids a delegation of the law-making power. In other words, assuming (but not deciding) that the challenged delegation, if it were confined to internal affairs, would be invalid, may it nevertheless be sustained on the ground that its exclusive aim is to afford a remedy for a hurtful condition within foreign territory?

It will contribute to the elucidation of the question if we first consider the differences between the powers of the federal government in respect of foreign or external affairs and those in respect of domestic or internal affairs. That there are differences between them, and that these differences are fundamental, may not be doubted.

The two classes of powers are different, both in respect of their origin and their nature. The broad statement that the federal government can exercise no powers except those specifically enumerated in the Constitution, and such implied powers as are necessary and proper to carry into effect the enumerated powers, is categorically true only in respect of our internal affairs. In that field, the primary purpose of the Constitution was to carve from the general mass of legislative powers then possessed by the states such portions as it was thought desirable to vest in the federal government, leaving those not included in the enumeration still in the states. Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238, 294.[1] That this doctrine applies only to powers which the states had, is self-evident. And since the states severally never possessed international powers, such powers could not have been carved from the mass of state powers but obviously were transmitted to the United States from some other source. During the colonial period, those powers were possessed exclusively by and were entirely under the control of the Crown. By the Declaration of Independence, “the Representatives of the United States of America” declared the United [not the several] Colonies to be free and independent states, and as such to have “full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.”

As a result of the separation from Great Britain by the colonies acting as a unit, the powers of external sovereignty passed from the Crown not to the colonies severally, but to the colonies in their collective and corporate capacity as the United States of America. Even before the Declaration, the colonies were a unit in foreign affairs, acting through a common agency – namely the Continental Congress, composed of delegates from the thirteen colonies. That agency exercised the power of war and peace, raised an army, created a navy, and finally adopted the Declaration of Independence. Rulers come and go; governments end and forms of government change; but sovereignty survives. A political society cannot endure without a supreme will somewhere. Sovereignty is never held in suspense. When, therefore, the external sovereignty of Great Britain in respect to the colonies ceased, it immediately passed to the Union. See Penhallow v. Doane, 3 Dall. 54, 80-81.[2] That fact was given practical application almost at once. The treaty of peace, made on September 23, 1783, was concluded between his Britannic Majesty and the “United States of America.” 8 Stat. – European Treaties – 80.

The Union existed before the Constitution, which was ordained and established among other things to form “a more perfect Union.” Prior to that event, it is clear that the Union, declared by the Articles of Confederation to be “perpetual,” was the sole possessor of external sovereignty and in the Union it remained without change save in so far as the Constitution in express terms qualified its exercise. The Framers’ Convention was called and exerted its powers upon the irrefutable postulate that though the states were several their people in respect of foreign affairs were one. Compare The Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U.S. 581, 604, 606. In that convention the entire absence of state power to deal with those affairs was thus forcefully stated by Rufus King:

The states were not “sovereigns” in the sense contended for by some. They did not possess the peculiar features of sovereignty, – they could not make war, nor peace, nor alliances, nor treaties. Considering them as political beings, they were dumb, for they could not speak to any foreign sovereigns whatever. They were deaf, for they could not hear any propositions from such sovereign. They had not even the organs or faculties of defence or offence, for they could not of themselves raise troops, or equip vessels, for war. 5 Elliott’s Debates 212.

It results that the investment of the federal government with the powers of external sovereignty did not depend on the affirmative grants of the Constitution. The powers to declare and wage war, to conclude peace, to make treaties, to maintain diplomatic relations with other sovereignties, if they had never been mentioned in the Constitution, would have vested in the federal government as necessary concomitants of nationality. . . .

Not only, as we have shown, is the federal power over external affairs in origin and essential character different from that over internal affairs, but participation in the exercise of the power is significantly limited. In this vast external realm, with its important, complicated, delicate, and manifold problems, the President alone has the power to speak or listen as a representative of the nation. He makes treaties with advice and consent of the Senate; but he alone negotiates. Into the field of negotiation the Senate cannot intrude; and Congress itself is powerless to invade it. As Marshall said in his great argument of March 7, 1800, in the House of Representatives, “The President is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations.” Annals, 6th Cong., col. 613. The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations at a very early day in our history (February 15, 1816), reported to the Senate, among other things, as follows:

The President is the constitutional representative of the United States with regard to foreign nations. He manages our concerns with foreign nations and must necessarily be most competent to determine when, how, and upon what subjects negotiations may be urged with the greatest prospect of success. For his conduct he is responsible to the Constitution. The committee consider this responsibility the surest pledge for the faithful discharge of his duty. They think the interference of the Senate in the direction of foreign negotiations calculated to diminish that responsibility and thereby to impair the best security for the national safety. The nature of transactions with foreign nations, moreover, requires causation and unity of design, and their success frequently depends on secrecy and dispatch. U.S. Senate, Reports, Committee on Foreign Relations, vol. 8, p. 24.

It is important to bear in mind that we are here dealing not alone with an authority vested in the President by an exertion of legislative power, but with such an authority plus the very delicate, plenary and exclusive power of the President as the sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations – a power which does not require as a basis for its exercise an act of Congress but which, of course, like every governmental program, must be exercised in subordination to the applicable provisions of the Constitution. It is quite apparent that if, in the maintenance of our international relations, embarrassment – perhaps serious embarrassment – is to be avoided and success for our aims achieved, congressional legislation which is to be made effective through negotiation and inquiry within the international field must often accord to the President a degree of discretion and freedom from statutory restriction which would not be admissible were domestic affairs alone involved. Moreover, he, not Congress, has the better opportunity of knowing the conditions which prevail in foreign countries, and especially is this true in time of war. He has confidential sources of information. He has his agents in the form of diplomatic, consular, and other officials. Secrecy in respect of information gathered by them may be highly necessary, and the premature disclosure of it productive of harmful results. Indeed, so clearly is this true that the first President refused to accede to a request to lay before the House of Representatives the instructions, correspondence, and documents relating to the negotiation of the Jay Treaty – a refusal the wisdom of which was recognized by the House itself and has never since been doubted.[3] . . .

- 1. In Carter v. Carter Coal (1936), the Supreme Court continued to hold a distinction between commerce and manufacturing in order to limit the reach of Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce. The presumptive logic at work is that the states retain the control over commerce if the Constitution does not give power to Congress to regulate it.

- 2. Pennhallow v. Doane’s Administrators (1795) is an obscure Supreme Court ruling that allowed federal courts in some instances to continue under the jurisdiction of laws passed under the Articles of Confederation.

- 3. Jay’s Treaty (1795) prevented potential war with England but deepened partisan divisions between Federalists and Republicans. In the middle of this partisan maneuvering, President George Washington set an early precedent of something like executive privilege, refusing the House’s request to turn over certain materials regarding the diplomatic negotiations between the two nations. However, Washington did give the documents to the Senate, and he eventually turned over some of the documents to the House.

Houses of Hospitality

December, 1936

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.