American Presidency

Woodrow Wilson was probably right when he said that it is easier to speak of presidents than it is of the presidency.[1] Because the presidency is held by only one person at a time, and because there have been only forty-five men who have held the office, the study of the presidency invites biography as its most obvious mode of analysis. This approach undeniably has some benefits for the student who wishes to know how a leader’s character, education, and experience affects the decisions he makes. In this sense, the study of the presidency offers the study of statesmanship by offering case studies in decision-making.

This volume, however, is aimed at a different approach, as it aspires to study the presidency above and beyond the men who have been president. More precisely, this volume treats the presidency as an ongoing series of questions, questions about the president’s duty to defend the Constitution and execute the laws while at the same time leading and representing a changing constitutional democracy. Thus this volume treats the presidency as a dialogue among those who have made it. These persons include presidents, but they also include members of Congress and justices on the Supreme Court, as well as the intellectuals whose writings have shaped important changes to the office.

The volume adopts this approach because the presidency today continues to challenge analysis just as it continues to rise above biography as the best means of analysis. Does the president have the power to reclassify the immigration status of millions of persons? Can the president fire an independent counsel? What does it mean to say the president can decide whether there will be war or not? These questions are ripped from the headlines, but the headlines could be from this decade or any of several others.

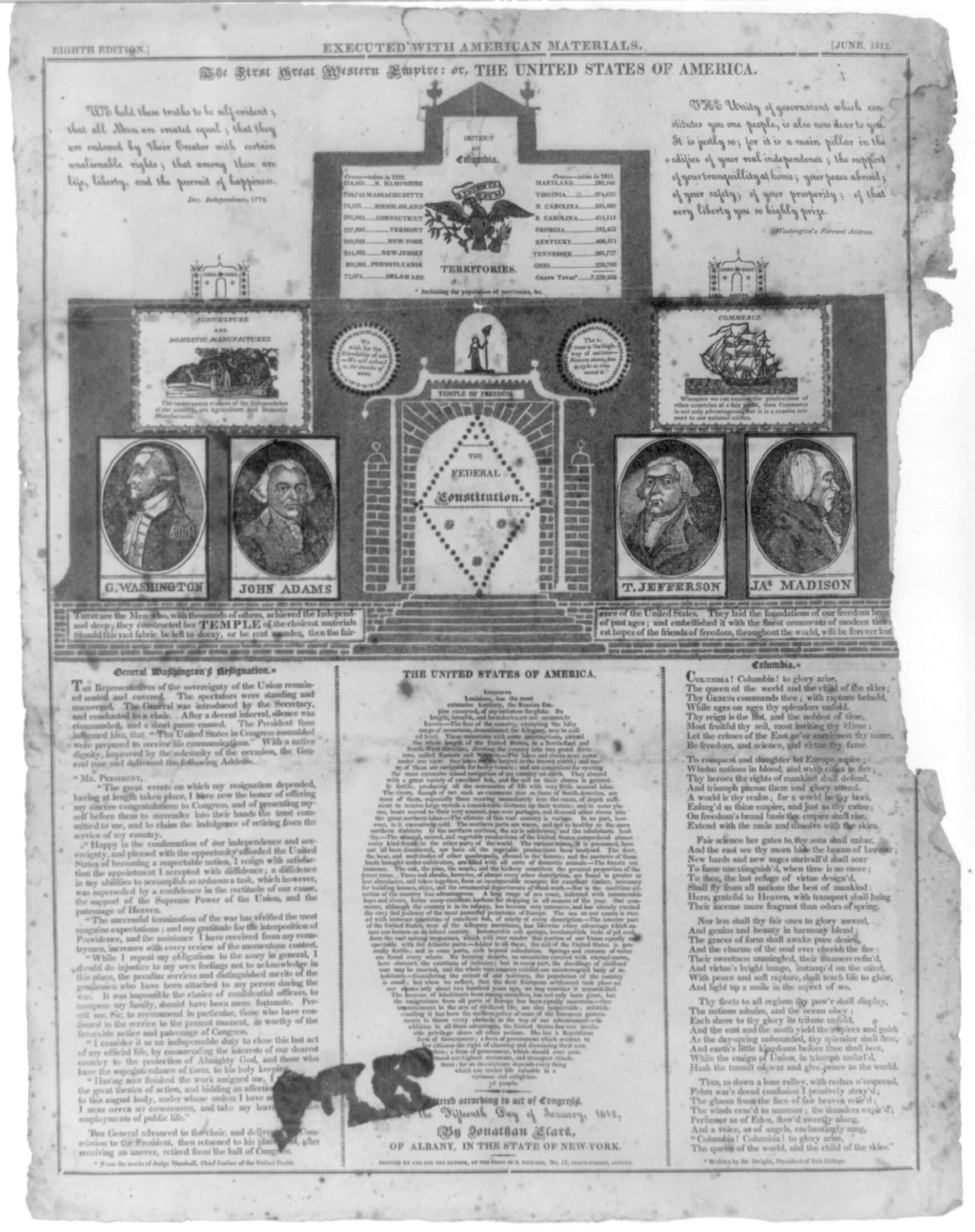

This uncertainty over the length and breadth of the president’s power comes not only because the Constitution does not and cannot settle every political controversy, but also because the Constitution begins its own presentation of the presidency with a kind of puzzle. Article Two states, “The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” This presumes that there is a power or a set of powers that can be identified as executive even before there is a constitution. That means that either by nature or by custom, the executive power exists and can be identified. This is further suggested by the fact that Article One gives Congress only the legislative powers “herein granted,” that is, those specifically listed in the Constitution, presumably in Article One, Section 8. The problem, however, is that Article Two also goes on to list the powers given to the president in Section Two, leading many commentators to argue that Article Two should be read in the same way as Article One. Others argue that the Constitution intended the difference between Articles One and Two, and that this difference suggests that the president has all the executive power, while Congress only has those legislative powers herein granted.

This puzzle is only partially the result of the language of the text, because there is a deeper problem in designing the presidency. As the executive, the president’s job is to execute the laws. This is the first principle of separation of powers: he who makes laws cannot execute them. In the context of England, separation of powers was first and foremost a check on kingly power. In the context of the United States of the 1780’s, however, separation of powers was accepted as an article of faith, but it was employed to be a check on legislative power. So the Framers of the Constitution made special effort not only to have a separate executive, but also an independent executive, that is, a president with his own electoral constituency and source of authority. But even with this innovation there remained an underlying feature of monarchical discretion. The person who executes the laws will also be the one to determine whether and when to execute the laws. Even if this does not mean the president has the power to make new law, it does reveal that the president as executive is not necessarily simply the enforcement arm of Congress. Rather, as Madison explains in Federalist No. 51, each department is given a “will of its own.” With its own will, and with the unusual wording of the Vesting Clause at the beginning of Article Two, the presidency is an institution that forces serious reflection on what it means to live under the rule of law.

Each of the selections in this volume can be grouped with others and is meant to start a conversation about the presidency. Does the Constitution give the war power to the president or to Congress? Who elects presidents and whom do presidents represent? Can the president remove any executive branch official for any reason, or can Congress create offices that exist beyond the supervisory role of the Chief Executive? Does the Constitution give the president the power to break the law? These questions are enduring not only because we disagree about their answers but also because we disagree about how we should answer them, or rather about who should answer. This volume, then, is first and foremost an invitation to teachers and students to join the dialogue suggested by the documents. Rather than offering a series of precedents or important historical events, the documents offer opportunities for close study and will reward the instructor who can find the time for extended discussion.

It is important to note that my claim that these questions are enduring has some bearing on an important part of teaching the presidency. I have in mind the modern presidency. Several selections in this volume will invite students to reflect upon the emergence and importance of a modern presidency, but others will invite students to ask whether a deeper continuity is the more important story when it comes to the development of the presidency. That is, teachers and students should not take the modern presidency thesis for granted. Like other textbook accounts of the presidency, it has to be assessed in light of the evidence.

In closing, I am grateful to Allison Brosky, who transcribed these documents. Two anonymous readers for the press helped me decide which texts were important and pointed me to several that I had not considered. Sarah Morgan Smith and David Tucker were generous and clear in their editorial guidance. Finally, I want to thank the professors who taught me the presidency, including Michael Nelson at Rhodes College, Sid Milkis at Brandeis University, and Marc Landy and Bob Scigliano at Boston College. Thanks to these men, I have been thinking about these documents since 1992, and I hope it gives them some pleasure to see my own attempt to pull them into a single volume.

This publication was made possible through the support of a grant by the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the editors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

[1] Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 1908), 54.

The Presidency and the Constitutional Order

–Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 70 (1788)

–Cato 4 (1788)

–President Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address

(March 4, 1801)

–President Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address

(March 4, 1861)

–Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government (1908)

–Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, On the Source of Executive Power (1913 and 1916)

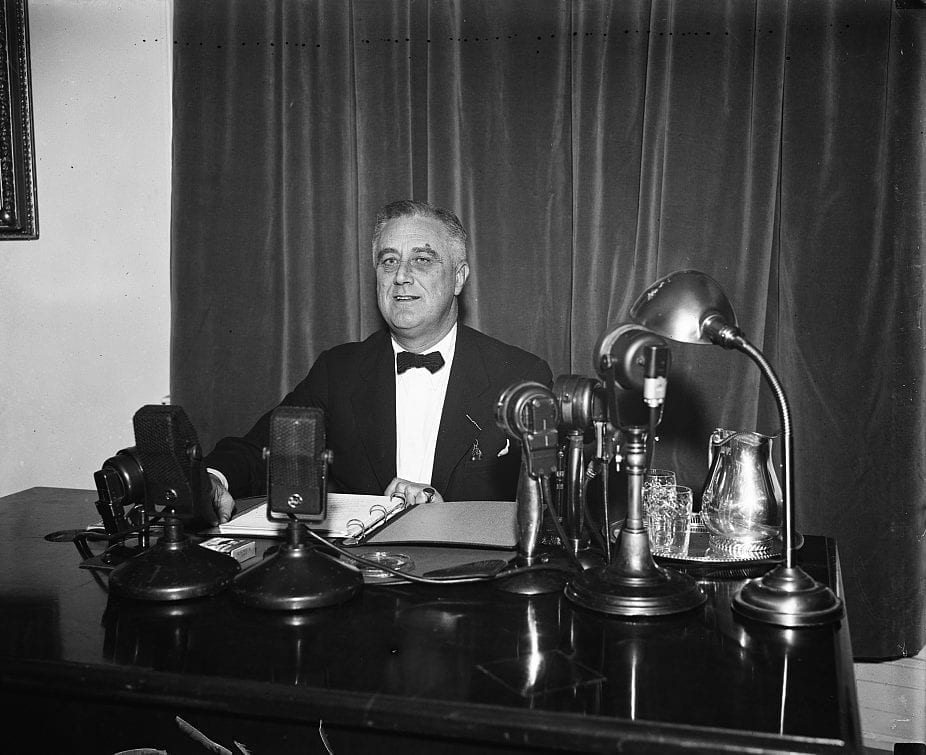

–President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address

(March 4, 1933)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on the

Reorganization of the Judiciary (March 9, 1937)

–John F. Kennedy, “The Presidency in 1960” (January 14, 1960)

Presidential Selection

–Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 68 (1788) –Delaware General Assembly, Resolution Rejecting the 12th

Amendment (1804) –President Andrew Jackson, First Annual Message (December 8, 1829)

–President John Tyler, Speech on Assuming the Office of the

President (April 9, 1841)

–The McGovern–Fraser Commission Report (1971)

Term Limit

–Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, Nos. 71–72 (1788)

–President Thomas Jefferson, Letter to the New Jersey Legislature (December 10, 1807)

–Representative John McCormack and Representative Chauncey Reed, House Debate on the 22nd Amendment (1947)

War Power and Control of Foreign Policy

–Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, Helvidius–Pacificus

Debate on Neutrality Proclamation (June–August 1793)

–Associate Justice George Sutherland, United States v. Curtiss–

Wright Export Co. (1936)

–President Harry Truman, Special Message to the Congress

–Reporting on the Situation in Korea (July 19, 1950)

–United States Congress and President Richard Nixon, War

Powers Resolution and Veto (1973)

–John C. Yoo, On the President’s Constitutional Authority to

Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists (2001)

–President Barack Obama, Special Address to the Nation on Syria (September 10, 2013)

Removal Power and Faithful Execution of the Laws

–Representative James Madison, Remarks on the Removal

Power: Speech in Congress (June 16, 1789) and Letter to Edmund Pendleton (June 21, 1789)

–President George Washington, Proclamation on the Whiskey

Rebellion (August 7, 1794)

–President Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Elias Shipman and Others (July 12, 1801)

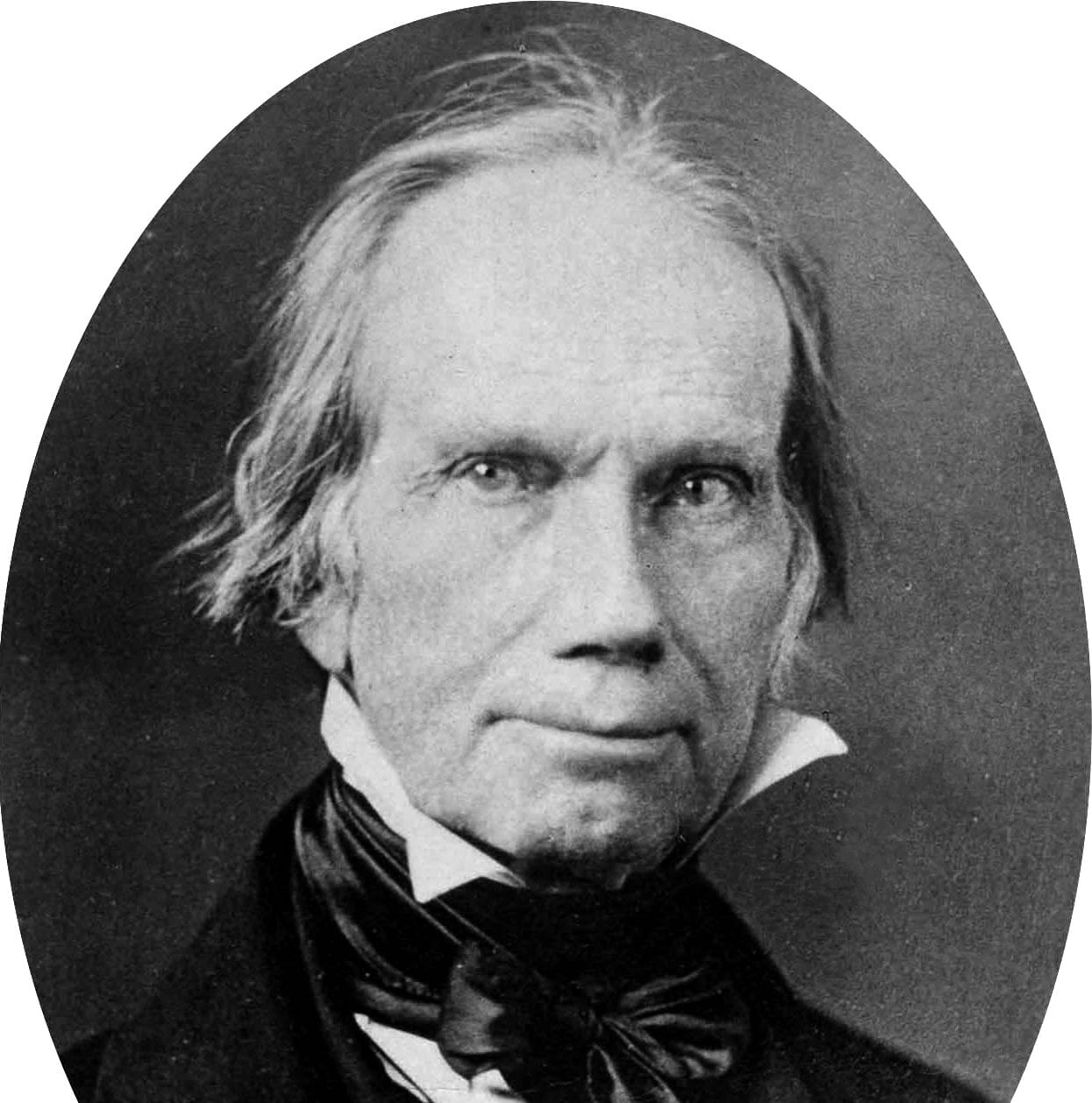

–Senator Henry Clay, Speeches on the Removal Power

(December 26, 1833 and March 7, 1834)

–President Andrew Jackson, Message to the Senate Protesting

Censure Resolution (April 15, 1834) –President Andrew Johnson, Third Annual Message (December 3, 1867)

–Chief Justice William Howard Taft (majority) and Associate

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (dissenting), Myers v. US (1926)

–Associate Justice George Sutherland, Humphrey’s Executor v.

United States (1935)

–The President’s Committee on Administrative Management,

“The Brownlow Committee Report” (1937)

Emergency Powers and Civil Liberties during Wartime

–Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John B. Colvin (September 20, 1810)

–President Abraham Lincoln, Message to Congress in Special

Session (July 4, 1861)

–President Abraham Lincoln, Letter to Albert G. Hodges

(April 4, 1864)

–Associate Justice David Davis, Ex parte Milligan (December 1866)

–Associate Justice Robert Jackson (concurring), Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952)

–Richard Nixon, Interview on the Huston Plan (1977)

–John C. Yoo, On the President’s Constitutional Authority to

Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists (2001)

–Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy (majority) and Associate

Justice Antonin Scalia (minority), Boumediene v. Bush (2008)

Impeachment

–Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, No. 65 (1788)

–President Andrew Jackson, Message to the Senate Protesting the Censure Resolution (April 15, 1834)

–House of Representatives, The Trial of Andrew Johnson,

President of the United States (1868)

–House of Representatives, Articles of Impeachment Against

President William Jefferson Clinton (1998)

For each of the documents in this collection, we suggest below questions relevant for that document alone and questions that require comparison between documents.

1. Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Nos. 65, 68, 70–72, 1788

- Why does Hamilton have to defend “energy” in the executive? What role does accountability play in Hamilton’s discussion of executive energy? What does the discussion of duration in office reveal about the character of the people who will be president?

- Does Hamilton’s account of the impeachment process reflect the impeachment process as it has played out over time? (Protesting the Censure Resolution (1834), Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (1868), First Inaugural Address (1933)). What about the Electoral College? Is it “excellent,” if “not perfect,” as he claims? Given the developments discussed in Rejecting the 12th Amendment (1804) and McGovern-Fraser Report (1971), to what extent does the Electoral College still function in the way that Hamilton and the other framers understood it would?

2. Cato No. 4, 1788

- According to Cato, what will enhance the formal powers of the president? What is wrong with the procedures for electing the president and vice-president? What does he find fault with in the provision for a vice-president?

- Do Cato and Publius (1788) have in mind the same kind of United States? Were Cato’s concerns about the language of Article II misplaced? Did he, for example, anticipate Senator Henry Clay’s critique of President Andrew Jackson (1834), or the difficulties Congress in the twentieth century would face in holding on to the war power (Youngstown Sheet & Tube (1952); Nixon, War Powers and Resolution (1973))?

- The Constitution is silent on who holds the power to remove executive branch officials. What possible answers to the puzzle emerged in 1789? What is the logic of Madison’s position, and how does the principle of responsibility fit into it?

- Does Madison’s argument here necessarily show an inconsistency with his argument as Helvidius (1793)? Can the two positions be made compatible?

- Who has the better understanding of the Constitution, Hamilton or Madison? If Hamilton is right, what are the limits to the president’s powers of war and peace? If Madison is right, what are the implications for foreign policy?

- Do Hamilton’s arguments as Pacificus shed light on his arguments in The Federalist, Nos. 70–72 (1788)? Why didn’t he mention the Vesting Clause in The Federalist?

5. President George Washington, Proclamation on the Whiskey Rebellion, August 7, 1794

- What alternatives did Washington have in dealing with the Whiskey Rebellion? What might his opponents have found objectionable in the proclamation?

- Is Washington’s proclamation an example of unilateral activity, that is, of the president acting alone? Or is it an example of working with Congress? How is it like or unlike his Neutrality Proclamation (1793)?

6. President Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural, March 4, 1801

- Jefferson’s address is famous today for being conciliatory toward Federalists, but in its day the Federalists found much to criticize in the address. What might they have found objectionable? What does Jefferson say should guide the country during moments of terror or alarm? What is the role of the president that is suggested near the end?

- To what extent does Jefferson’s address line up with the presentation of the president in The Federalist (1788)? How do Jefferson’s arguments compare to those of Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in 1793, or to the assumptions about executive power evident in the Whiskey Rebellion (1794)?

7. President Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Elias Shipman and Others, July 12, 1801

- Why did Jefferson have to defend his removal of Goodrich? What is the basis for this power according to Jefferson?

- In what ways does Jefferson’s explanation resemble James Madison’s case for removal powers (1789)? In what ways is it different? How might this letter clarify Jefferson’s First Inaugural (1801)?

8. Delaware General Assembly, Resolution Rejecting the 12th Amendment, 1804

- According to Delaware’s legislature, what is the problem with the Twelfth Amendment? Why does Delaware want to retain five as the number of candidates available to the House in the contingency election? How might this affect the separation of powers, or the relative influence of small and large states?

- How does Delaware’s understanding of presidential selection compare to Thomas Jefferson’s vision for the presidency (First Inaugural Address (1801); Letters to Elias Shipman & Others (1801))? How does each line up with the logic of Federalist No. 68 (1788)?

9. President Thomas Jefferson, Letter to the New Jersey Legislature, December 10, 1807

- How does Jefferson’s public explanation of his decision to retire compare to or cast new light on President George Washington’s precedent? What is implied about Washington in Jefferson’s letter?

- What would Alexander Hamilton, the author of Federalist No. 72 (1788), say in response to Jefferson? Does Jefferson’s principle weaken the “will” necessary for presidents to carry out extensive and arduous enterprises?

10. Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John B. Colvin, September 20, 1810

- How are Jefferson’s first three examples of extra-legal actions similar to one another? In what way does his hypothetical about Florida differ from these examples? What are the requirements for the officer who acts beyond the law? For the people who judge the officer’s action?

- How does Jefferson’s answer to Colvin compare to Alexander Hamilton’s and James Madison’s interpretations of the Vesting Clause in their respective arguments about the treaty power and the removal power (Helvidius-Pacificus (1793); Remarks on Removal Power (1789))?

11. President Andrew Jackson, First Annual Message, December 8, 1829

- How does Jackson’s proposal for direct election of the president correspond with the larger aims of Jackson’s political coalition? The proposal did not become part of the Constitution. What might have been the concerns of those against the idea?

- How would Jackson’s proposal alter the logic of Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 68 (1788)? How might the Delaware Legislature of 1804 respond to Jackson’s proposal?

12. Senator Henry Clay, Speeches in the Senate, December 26, 1833 and March 7, 1834

- Can Congress issue orders to a department head, orders that override the directives of the president? What is Clay’s concern with President Andrew Jackson’s argument about the purpose of presidential elections?

- Why does Clay believe that James Madison was wrong in 1789 (Remarks on the Removal Power) to argue that the Constitution gives the removal power to the president? Where might Madison place Clay’s views among the competing stances on the removal power he outlines in his letter to Pendleton?

- What is the problem with the censure from Jackson’s perspective? Why did he have to remove Treasury Secretary William Duane and what does the election of 1832 have to do with it?

- Do the essays in The Federalist (1788) leave a place for a motion of censure as an alternative to impeachment? Does Jackson’s case for removing Duane most resemble the argument of James Madison (Remarks on the Removal power (1789)) or that of Thomas Jefferson (Letter to Elias Shipman & Others (1801))? Or does Jackson offer his own theory?

14. President John Tyler, Speech on Assuming the Office of the President, April 9, 1841

- Does Tyler leave open the possibility that he would not finish President William Henry Harrison’s term? Is there another way he might have handled the situation? Can Tyler’s political commitments be discerned from the speech? Do they easily align with either the Whig or Democratic parties?

- In what ways does Tyler’s speech resemble the inaugural addresses of Presidents Abraham Lincoln (1861) and Thomas Jefferson (1801)? What do these similarites suggest about parties and party platforms?

15. President Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861

- According to Lincoln, what does his party’s platform reveal about his presidency? In his view, what does this platform suggest about the meaning of the election of 1860? What does this in turn reveal about the relationship between new presidents and the Supreme Court?

- To what extent does Lincoln’s treatment of his platform show continuity with the presidencies of Thomas Jefferson (First Inaugural Address (1801); Letters to Elias Shipman & Others (1801); Letter to the New Jersey Legislature (1807)) and Andrew Jackson (First Annual Message (1829); Protesting the Censure Resolution (1834))? To what extent does Lincoln’s discussion of the Supreme Court accord with the views of Jefferson and Jackson?

16. President Abraham Lincoln, Message to Congress in Special Session, July 4, 1861

- Why did critics say that Lincoln lacked the power to suspend habeas corpus? What is the significance of the oath of office in Lincoln’s explanation why he has the power to suspend habeas corpus? Does it matter that the Constitution allows the president to call Congress into special session?

- How does Lincoln’s use of presidential power compare to that of Presidents Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson? Does Lincoln rely on public opinion in this address, or does the source of his power reside elsewhere?

17. President Abraham Lincoln, Letter to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864

- What is the significance of the oath of office in Lincoln’s understanding of his power? Why does Lincoln insist that he does not have the power to end slavery simply on the basis of his own antislavery stance?

- How does Lincoln’s justification of the Emancipation Proclamation fit with his defense of suspending habeas corpus in (Message to Congress (1861))? How does it compare to Thomas Jefferson’s approach to presidential prerogative in Letter to John B. Colvin (1810)?

18. Associate Justice David Davis, Ex parte Milligan, December 1866

- To what extent does this case rest on the fact that the war never came to Indiana and to what extent does it rest on the fact that the war was over?

- Four Justices argued that the case turned on the fact that Congress had not specifically authorized the military commissions, while the majority argued that Congress could not make that authorization. How might the minority anticipate the logic of Associate Justice Robert Jackson’s concurring opinion in Youngstown (1952)?

19. President Andrew Johnson, Third Annual Message, December 3, 1867

- Why must the president have the power to remove, according to Johnson? Why is the Senate not the best institution for wielding the power?

- Does Johnson’s argument differ in any important respect from the arguments made by James Madison (Remarks on the Removal Power (1789)), Thomas Jefferson (Letters to Elias Shipman & Others (1801)), and Andrew Jackson (Protesting the Censure Resolution (1834))? Does the disagreement over Reconstruction complicate this constitutional controversy? Does it show that Senator Henry Clay was on to something in his speech in the Senate (1834)?

20. House of Representatives, The Trial of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, 1868

- In addition to violating the Tenure of Office Act, what were the charges against Johnson? Could those charges be made in the twentieth century, or do they suggest the expectations for presidents in the nineteenth century were different? What is the issue lurking underneath the stated charges?

- Does Alexander Hamilton’s discussion of impeachment in Federalist No. 65 (1788) anticipate the nature of the charges against Johnson? Does it matter that Johnson believed the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional?

21. Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government in the United States, 1908

- What does Wilson mean by a Newtonian theory of the Constitution? What does he mean by a Darwinian theory? How will the latter change the presidency?

- How does Wilson’s call for a new presidency fit within a call for a new theory of the Constitution? Does this argument fit within any of the others in this volume or is it one of a kind?

- Are there any limits on executive power under Roosevelt’s understanding? Is there any room for a strong president under Taft’s understanding?

- To what extent does Roosevelt’s understanding fit within Alexander Hamilton’s presentation of executive power in Federalist No. 70 (1788) and Pacificus (1793)?

- What is the role of accountability (or responsibility) in Taft’s reasoning? What is the role of the Take Care Clause?

- Does Taft’s opinion contradict his argument in On the Source of Executive Power (1916)? Which is closest to Taft’s logic, the arguments of James Madison (Remarks on the Removal Power (1789)), Thomas Jefferson (Letter to Elias Shipman & Others (1801)), or Andrew Jackson (Protesting the Censure Resolution (1834))? How does Justice Holmes’s dissenting opinion line up with Henry Clay’s critique (Speeches on the Removal power (1834)) of presidential removal powers?

24. Associate Justice George Sutherland, Humphrey’s Executor v. US, 1935

- According to the Court, what is the difference between a member of the Federal Trade Commission and a postmaster? Who gets to determine the difference? What if Congress believes one thing and the president another?

- To what extent does the decision in Humphrey’s Executor continue the logic of Senator Henry Clay’s critique of President Andrew Jackson (On the Source of Executive Power (1916)) and to what extent does it continue the logic of Associate Justice Oliver Holmes’s dissent in Myers (Myers v. US (1926))? To what extent does it argue something new?

25. Associate Justice George Sutherland, United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Co., 1936

- Why does the non-delegation doctrine not apply in this case, according to the Court? What is the significance of the argument about the historical location of sovereignty during the Revolution and during the framing and ratification of the Constitution? What are the limits to the president’s foreign policy powers under this argument?

- Does Sutherland go beyond even Alexander Hamilton as Pacificus (1793)? What might James Madison say in response to the Court in 1936?

26. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1933

- President Roosevelt argued in one of his campaign addresses that the social contract had to be renegotiated. Specifically, the country needed to use Hamiltonian means (a strong central government) to achieve Jeffersonian ends (equality). What measures will the government undertake to bring about this renegotiation? What is the role of the president in this process? Will this change our system of separated powers?

- Presidents Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Roosevelt resemble each other in certain ways. For example, each was a victor in a transformative election. Consider their inaugural addresses (Jefferson (1801); Lincoln (1861)). How are they similar, and how are they different?

- According to the members of the Brownlow Commission, what is new about the federal government in the 1930’s? What does this entail for the presidency? How likely is it that the president’s advisors would have a “passion for anonymity”?

- How do the Brownlow Commission’s recommendations square with the arguments on the removal power in (Remarks on the Removal Power (1789); Letter to Elias Shipman & Others (1801); Protesting the Censure Resolution (1834); Myers v. US (1926); Executor v. US (1935))? To what extent do its recommendations fall in line with Wilson’s call for a new presidency in On the Source of Executive Power (1916)?

- What is the significance of President Roosevelt’s three-horse team analogy? Where is the Constitution in that image? Roosevelt’s proposal promoted a backlash from conservative members of his own party. Why?

- To what extent is Roosevelt’s criticism of the Supreme Court similar to Abraham Lincoln’s in his First Inaugural Address (1801)? To what extent does Roosevelt go beyond Lincoln?

- What is argument for the amendment? What is the argument against it? Does either argument presuppose the existence of a modern presidency?

- Based on Federalist No. 72 (1788) and on the Letter to the New Jersey Legislature (1807), how might Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson have argued had they been present in 1947?

- Why does Truman place importance on the United Nations in his speech? By comparison, what is the role of Congress? What is the importance of the larger strategic imperatives of the Cold War? Of the fact that the conflict involved an aggressor nation?

- Does Truman’s presumption of authority over the war power go beyond that outlined by Hamilton in Pacificus (1793)? Does it go beyond that outlined by Justice Sutherland in Curtiss-Wright (1936)?

31. Associate Justice Robert Jackson (concurring), Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 1952

- Is Jackson’s opinion a ruling against Truman or a ruling against presidential power? What does he recommend that a judge do in each of the three practical situations he outlines?

- Can Jackson’s opinion be squared with the result in Curtiss-Wright (1936)? Is the difference that the question involves domestic action rather than foreign action? Or is the difference more fundamental?

- Where is the Constitution in Senator Kennedy’s conception of the presidency? Where is Congress? Does Kennedy believe that the modern presidency is somehow different from the constitutional presidency? Is Kennedy primarily concerned with presidential temperament or with a theory of power?

- Are there any differences between what Theodore Roosevelt described as having guided his presidency (Constitutional Government in the United States (1908)) and what Kennedy promises will guide his?

33. The McGovern–Fraser Commission Report, 1971

- The McGovern-Fraser Commission created the process by which we nominate presidential candidates today. What were the Commission’s goals?

- The Constitution did not anticipate national political parties, and so it could not have anticipated our nomination process today. That being said, to what extent does our nominating process line up with the expectations and goals outlined by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 68 (1788)?

34. The War Powers Resolution and President Richard Nixon’s Veto, 1973

- Congress overrode Nixon’s veto, but did he have the better argument? Or did Congress? Where does the Constitution place the war power? Why hasn’t the War Powers Resolution lived up to its purpose?

- How would Justices George Sutherland (US v. Curtiss Wright (1936)) and Robert Jackson (Youngstown Sheet (1952)) respond to the War Powers Resolution?

35. Transcript of David Frost’s Interview with Richard Nixon, 1977

- Does it matter whether the Huston Plan was designed to counteract foreign espionage or domestic opposition? Could Nixon have sought approval from Congress for this operation?

- Nixon’s assertion of executive prerogative clearly goes beyond that of Thomas Jefferson (Letter to John B. Colvin (1810)) and Abraham Lincoln (Message to Congress in Special Session (1861); Letter to Albert G. Hodges (1864)). But the more interesting question is whether Lincoln and Jefferson’s arguments necessarily lead to something like Nixon’s claim. Is there a way to make their arguments without leading to what Nixon says? Or, does either Jefferson or Lincoln offer the safer path for constitutional government?

- Why was President Bill Clinton impeached? Why didn’t a supermajority of the Senate support removal from office?

- Clinton’s defense argues that his crime was not “high” enough to be an impeachable offense. Does Federalist No 65 (1788) support that argument? In what ways are the charges against Clinton like those against President Andrew Johnson (1868)? In what ways are they different?

- According to Yoo, what is the meaning of “declare” in Congress’s power to declare war? What evidence does he employ to make this argument? What evidence does he ignore? Accoridng to Yoo, which provision of the Constitution better describes Congress’s power over war?

- Would Alexander Hamilton (The Federalist (1788); Pacificus (1793)) agree with Yoo’s reading of the Constitution with respect to the war power? Would Justice George Sutherland (US v. Curtiss-Wright (1936))?

- What, precisely, is at stake in the differences between Justices Kennedy and Scalia? Does it matter that the war on terror is different from conventional wars with specific nations?

- Does Justice Kennedy seem to have used the framework recommended by Justice Jackson in Youngstown (1952) in reaching his decision? If so, how?

39. President Barack Obama, Special Address to the Nation on Syria, September 10, 2013

- Does Obama believe he needs Congressional approval for military action against Syria? If not, what is the purpose of the message?

- How does Obama’s message compare to President Harry Truman’s speech on Korea (1950)? Which is more deferential to Congress? Which leaves the most room for executive authority?

Alvis, J. David, Jeremy D. Bailey, and F. Flagg Taylor. The Contested Removal Power, 1789-2010. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

Bailey, Jeremy D. Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Ceaser, James W. Presidential Selection: Theory and Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Ellis, Richard. The Development of the American Presidency. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Fisher, Louis. Presidential War Power. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

Goldsmith, Jack. The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment Inside the Bush Administration. New York: Norton, 2007.

Howell, William D. Power Without Persuasion: The Politics of Direct Presidential Action. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Kleinerman, Benjamin A. The Discretionary President: The Promise and Peril of Executive Power. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Knott, Stephen F. Secret and Sanctioned: Covert Operations and the American Presidency. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Landy, Marc and Sidney M. Milkis, Presidential Greatness. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Milkis, Sidney M. The President and the Parties: The Transformation of the American Party System Since the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Nichols, David K. The Myth of the Modern Presidency. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Press, 1994.

Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973.

Skowronek, Stephen. The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to George Bush. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 1993.

Slonim, Shlomo. “The Electoral College at Philadelphia: The Evolution of an Ad Hoc Congress for Selection of President,” Journal of American History 73: 1 (1986): 35-58.

Tulis, Jeffrey K. The Rhetorical Presidency. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.)