No related resources

Introduction

The Constitution is clear about how heads of departments are created: the president appoints them, subject to the advice and consent of the Senate. But the Constitution says nothing about how department heads are removed. Must the president seek the advice and consent of the Senate to remove a department head, or does the president have this power alone? Or does the Constitution leave this power to Congress to delegate as it pleases? Or is there some other constitutional device, like impeachment, for removals?

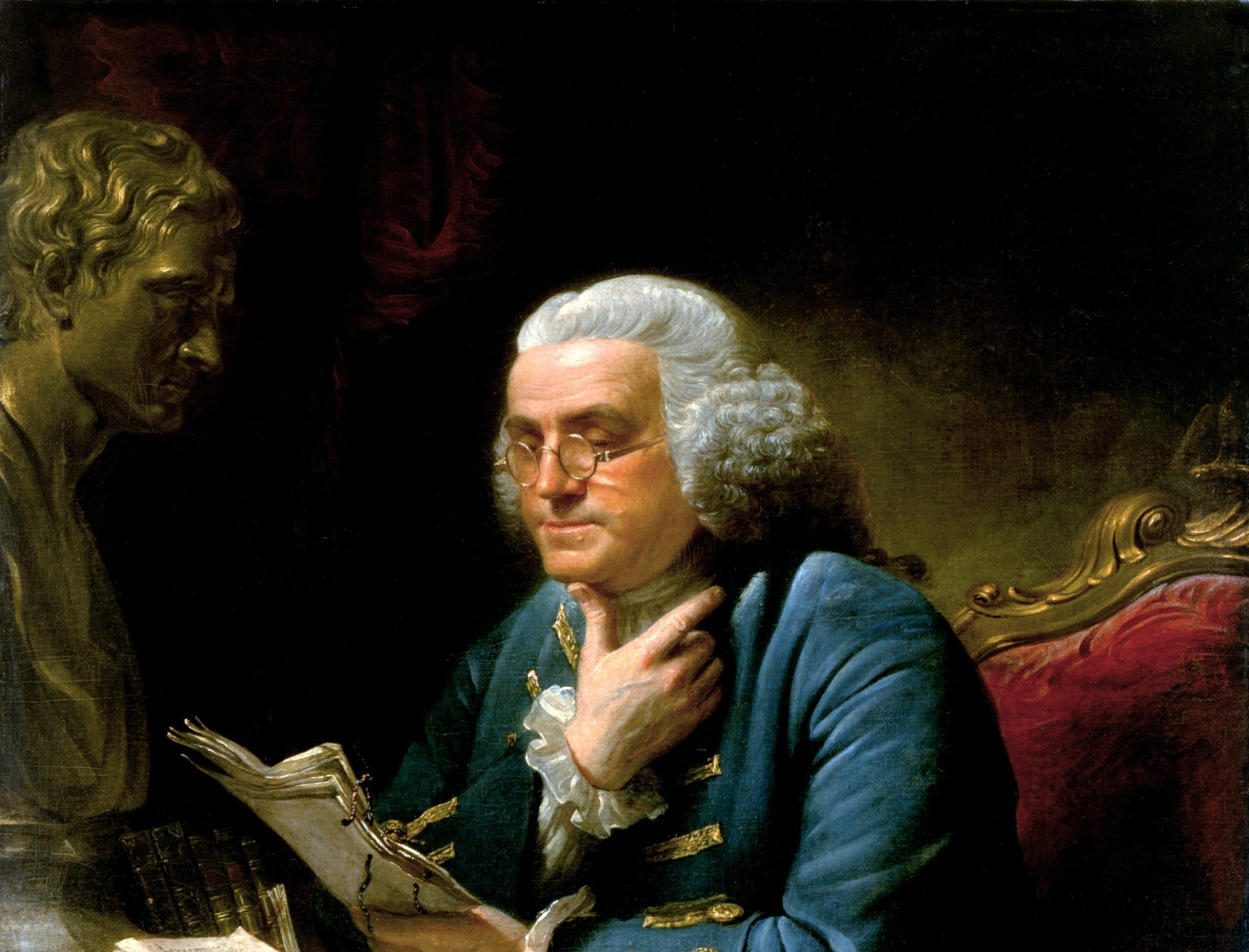

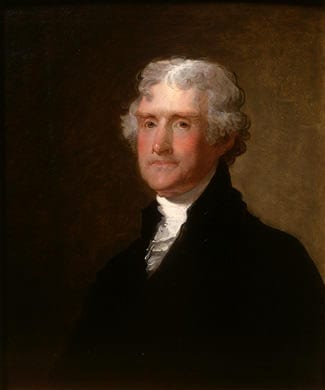

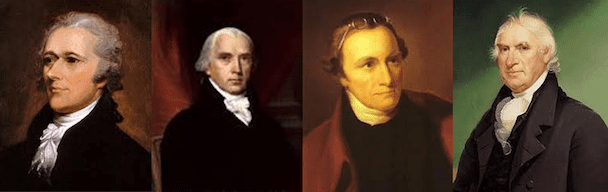

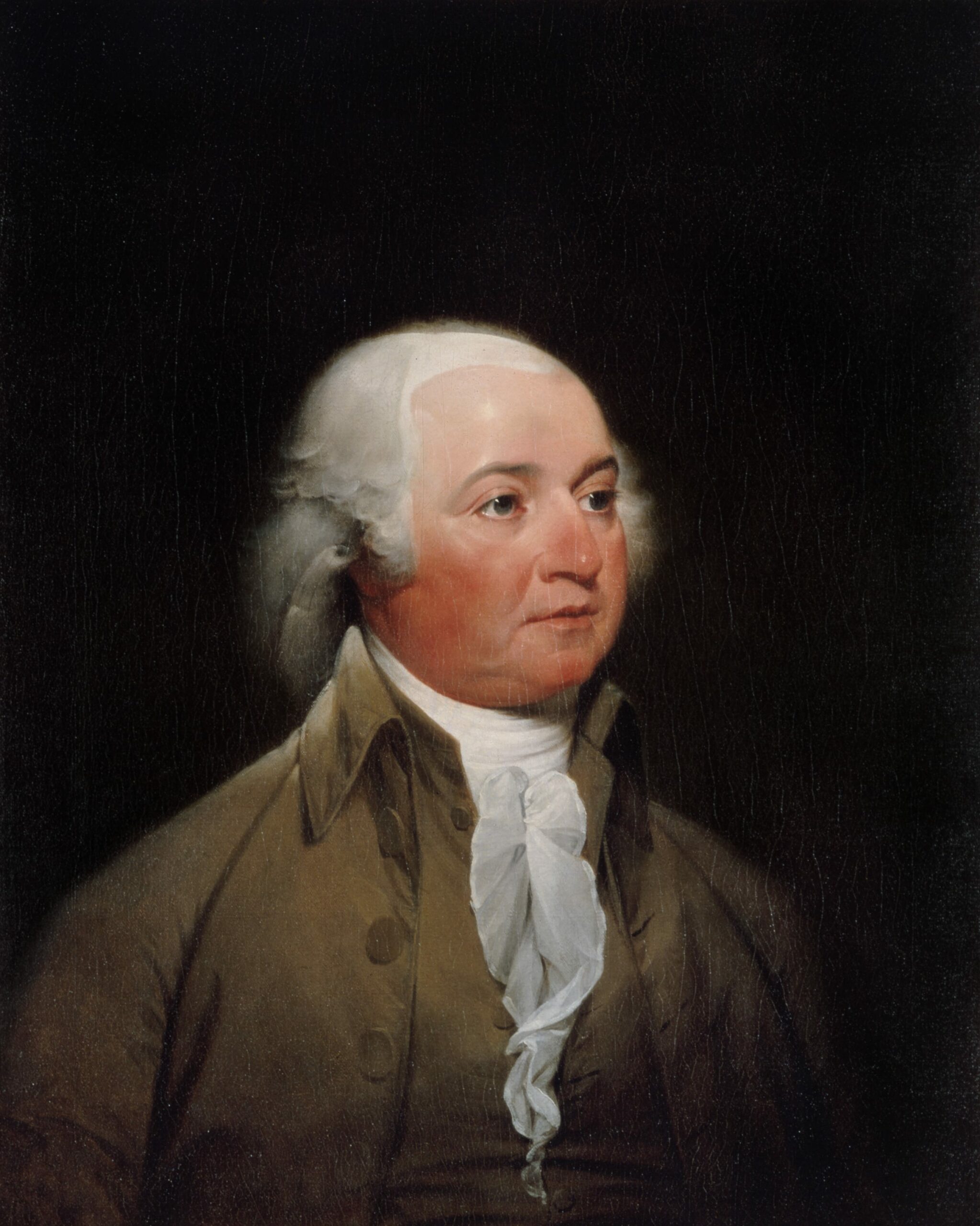

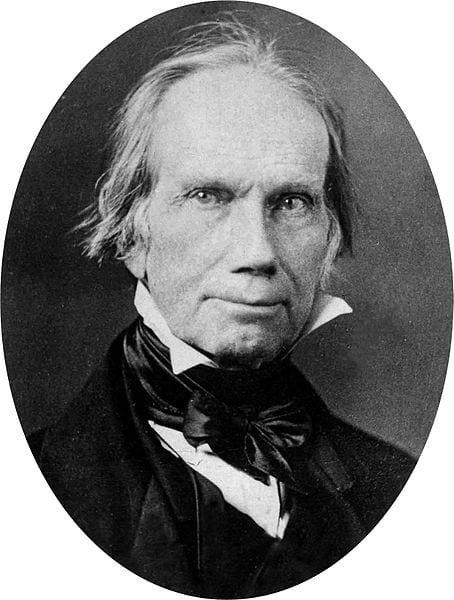

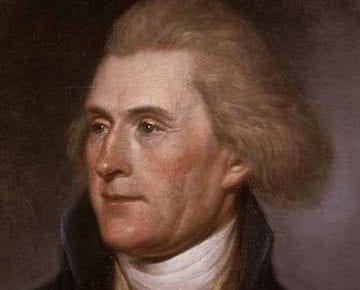

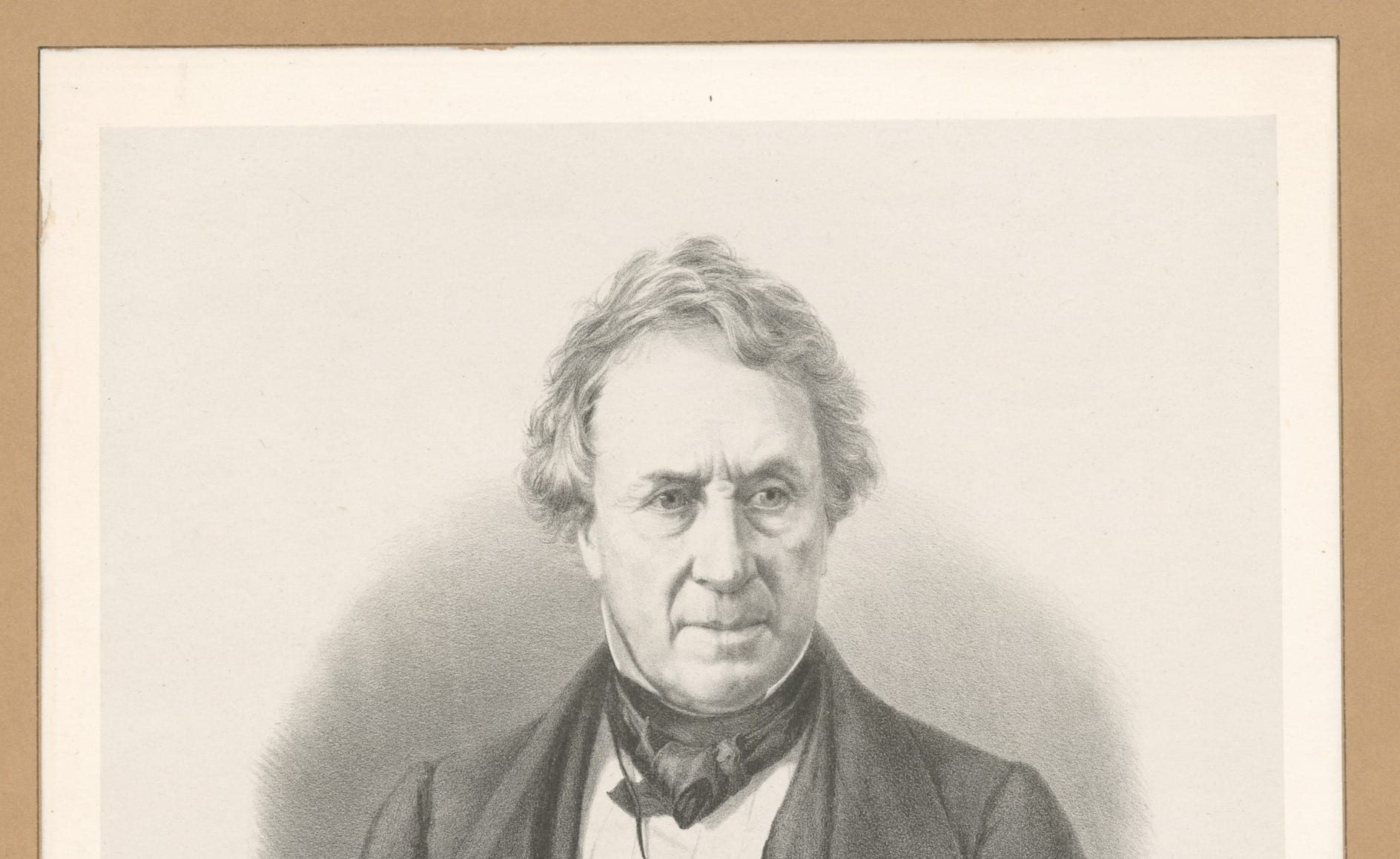

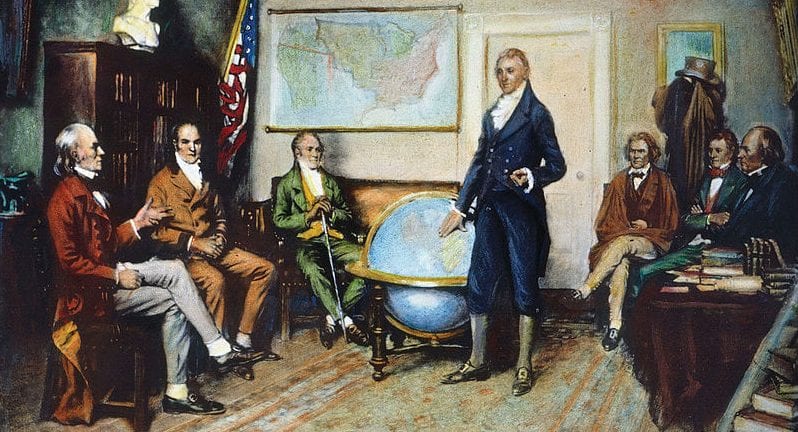

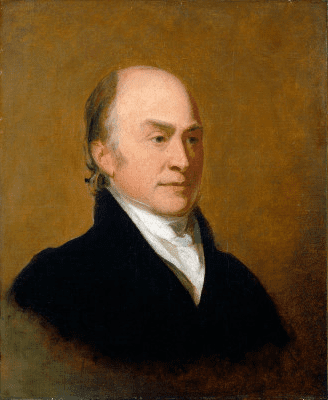

This question arose in the first Congress even before there were political parties. In the House, James Madison led the coalition that argued that the Constitution vested this power in the president alone. Notice how he justifies that power in the following speech on the House floor and in his account in the letter to fellow Virginian Edmund Pendleton (1721–1803). In addition to the argument about the principle of responsibility, or accountability, Madison points to the difference between the Vesting Clauses of Articles One and Two to make his case.

Source: James Madison, Speech on the Removal Power of the President, [16 June] 1789, Founders Online, National Archives, https://goo.gl/o2MFpz; “From James Madison to Edmund Pendleton, 21 June 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://goo.gl/dzrYqB.

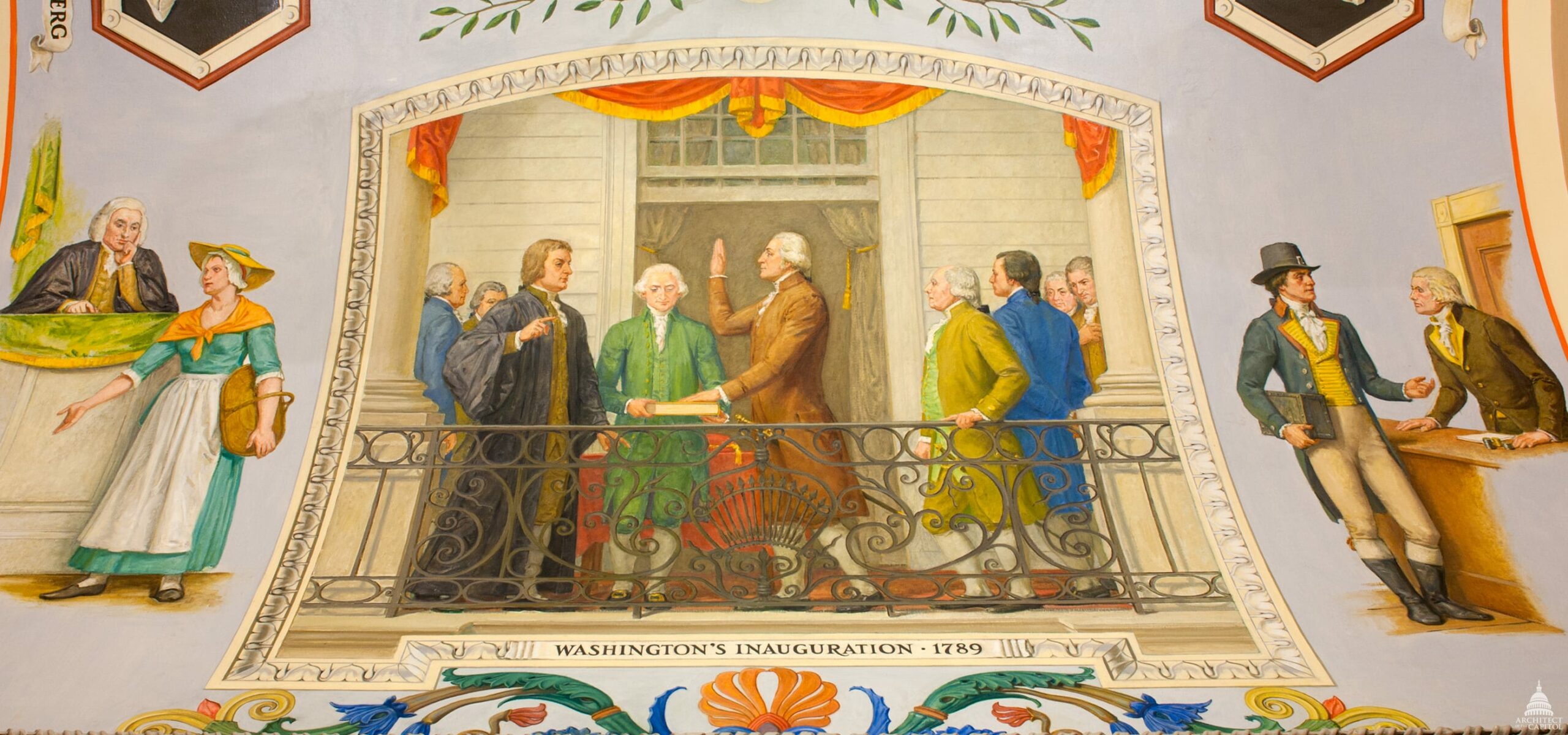

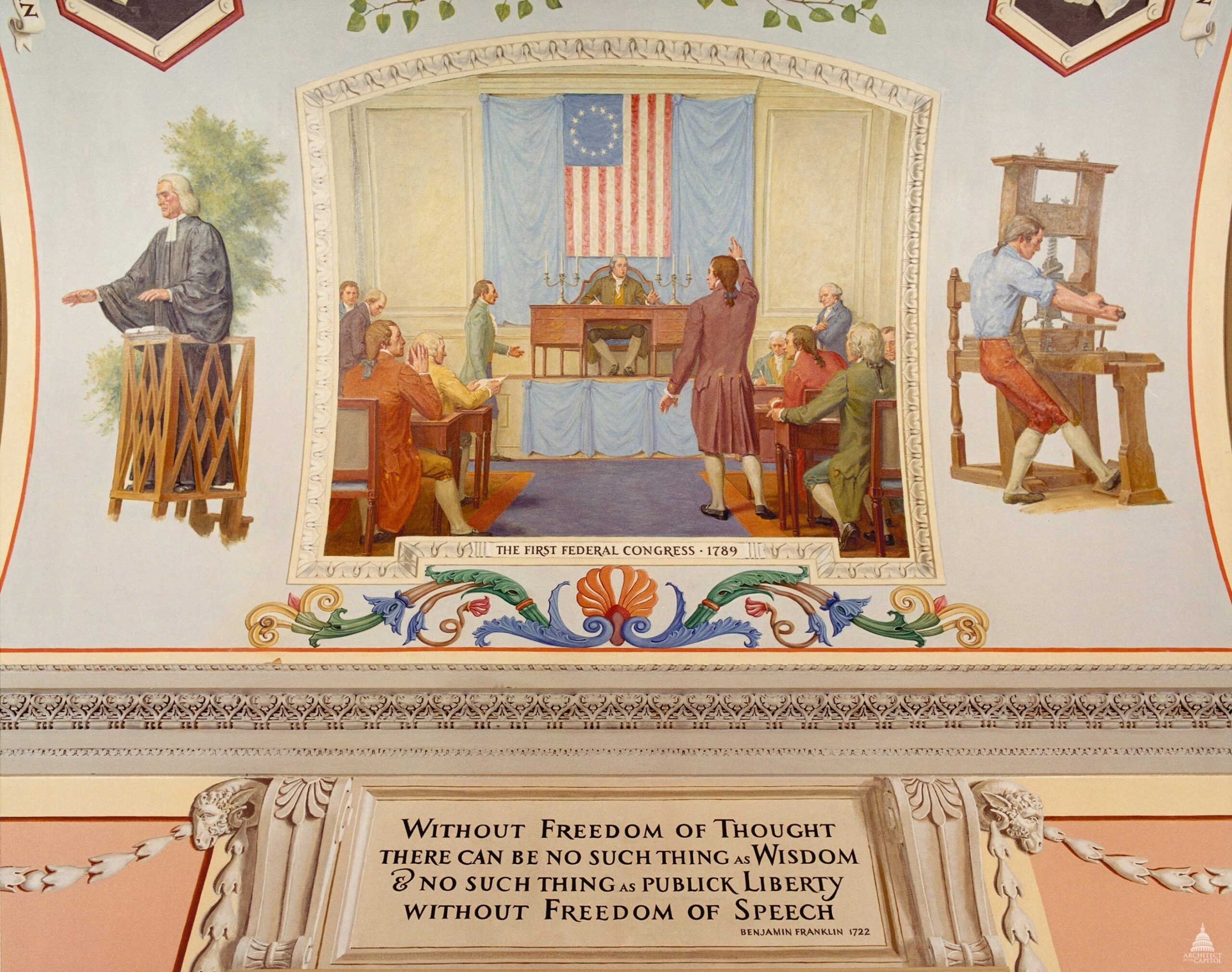

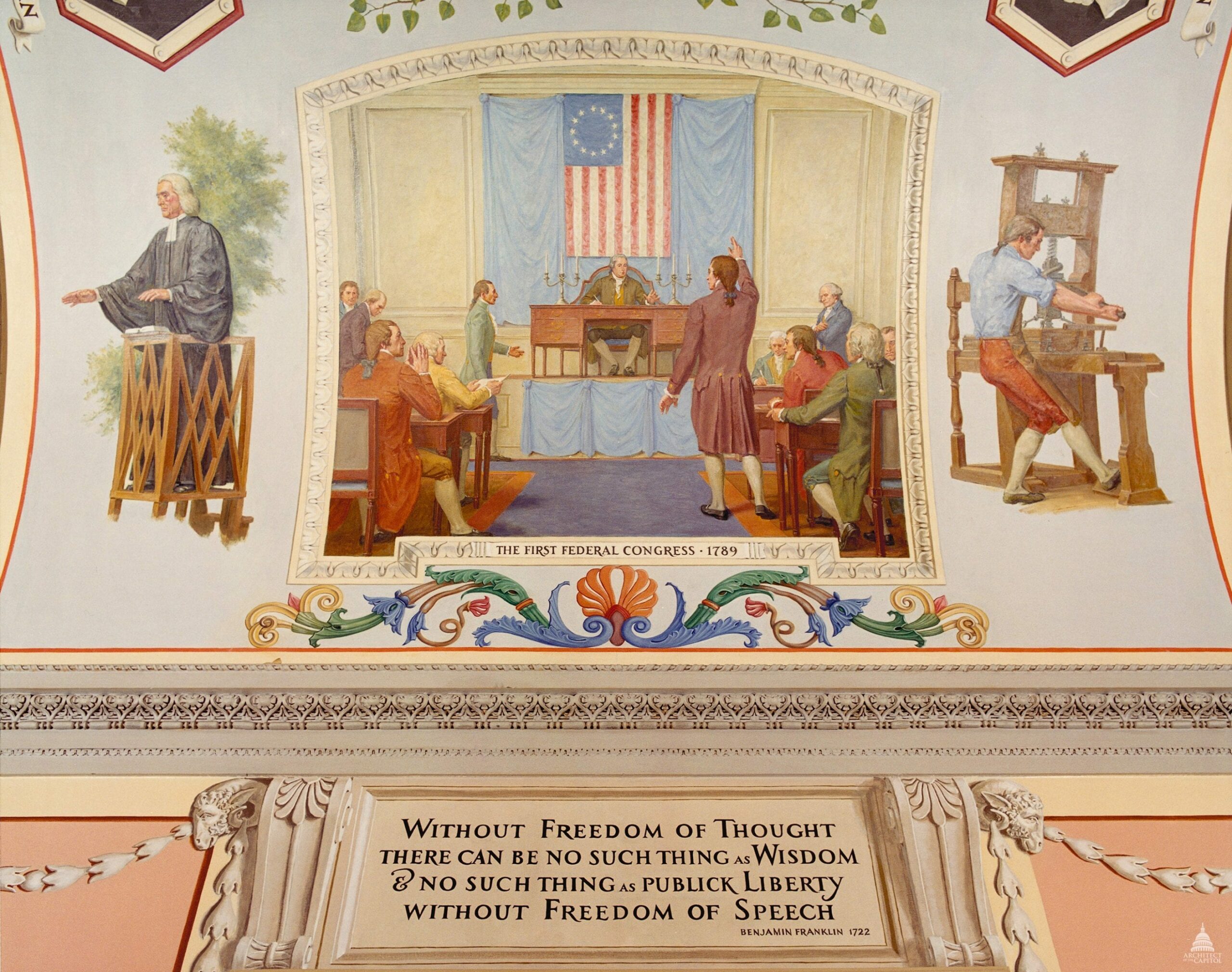

Madison’s Speech in Congress, June 16, 1789

The Committee of the Whole took up the bill establishing a department of foreign affairs. Smith (South Carolina) and others wished to strike out the clause declaring the secretary “to be removable from office by the President of the United States.”

MR. MADISON. If the construction of the Constitution is to be left to its natural course with respect to the executive powers of this government, I own that the insertion of this sentiment [“to be removable from office by the President of the United States”] in law may not be of material importance, though if it is nothing more than a mere declaration of a clear grant made by the Constitution, it can do no harm; but if it relates to a doubtful part of the Constitution, I suppose an exposition of the Constitution may come with as much propriety from the legislature as any other department of government. If the power naturally belongs to the government, and the constitution is undecided as to the body which is to exercise it, it is likely that it is submitted to the discretion of the legislature, and the question will depend upon its own merits.

I am clearly of opinion with the gentleman from South-Carolina (Mr. Smith,) … that we ought in this and every other case to adhere to the Constitution, so far as it will serve as a guide to us, and that we ought not to be swayed in our decisions by the splendor of the character of the present chief magistrate, but to consider it with respect to the merit of men who, in the ordinary course of things, may be supposed to fill the chair. I believe the power here declared is a high one, and in some respects a dangerous one; but in order to come to a right decision on this point, we must consider both sides of the question: The possible abuses which may spring from a single will of the first magistrate, and the abuse which may spring from the combined will of the executive and the senatorial qualification.

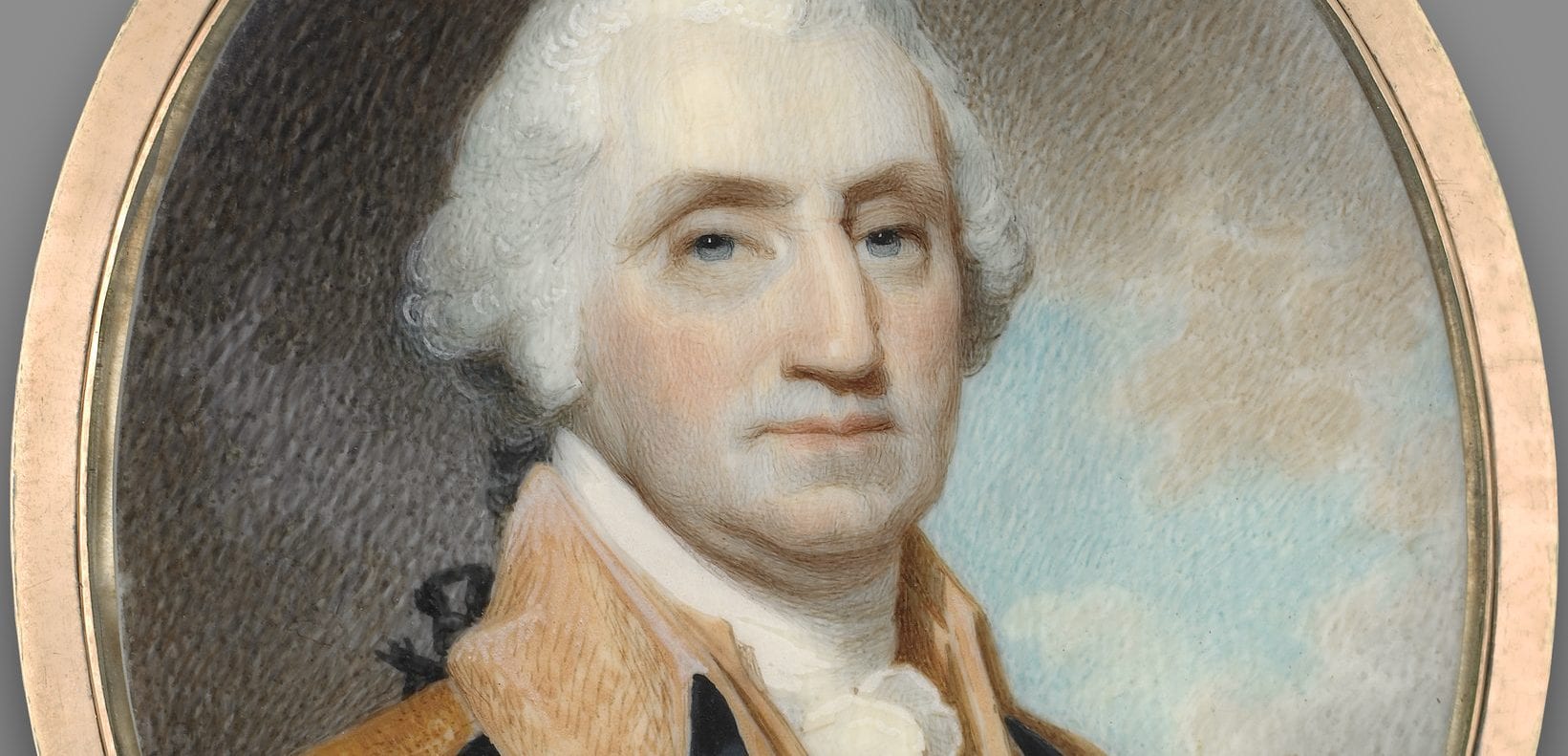

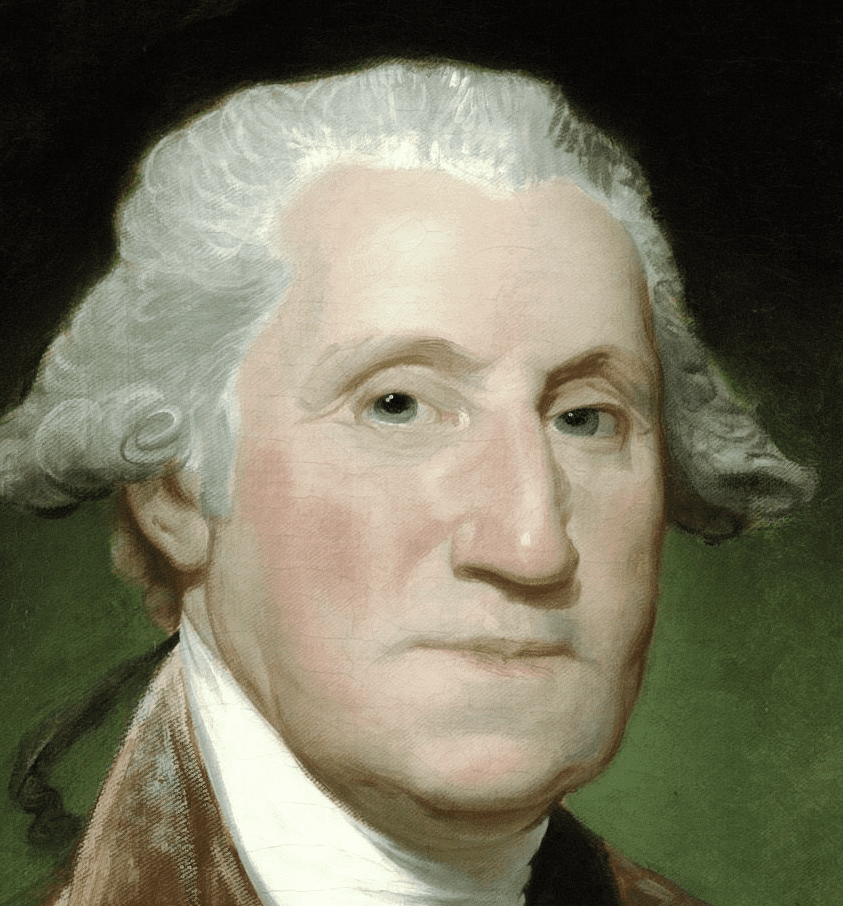

When we consider that the first magistrate is to be appointed at present by the suffrages of three millions of people, and in all human probability in a few years time by double that number, it is not to be presumed that a vicious or bad character will be selected. If the government of any country on the face of the earth was ever effectually guarded against the election of ambitious or designing characters to the first office of the state, I think it may with truth be said to be the case under the Constitution of the United States. With all the infirmities incident to a popular election, corrected by the particular mode of conducting it, as directed under the present system, I think we may fairly calculate, that the instances will be very rare in which an unworthy man will receive that mark of the public confidence which is required to designate the President of the United States. Where the people are disposed to give so great an elevation to one of their fellow citizens, I own that I am not afraid to place my confidence in him; especially when I know he is impeachable for any crime or misdemeanor, before the Senate, at all times; and that at all events he is impeachable before the community at large every four years, and liable to be displaced if his conduct shall have given umbrage during the time he has been in office. Under these circumstances, although the trust is a high one, and in some degree perhaps a dangerous one, I am not sure but it will be safer here than placed where some gentlemen suppose it ought to be.

It is evidently the intention of the Constitution that the first magistrate should be responsible for the executive department; so far therefore as we do not make the officers who are to aid him in the duties of that department responsible to him, he is not responsible to his country. Again, is there no danger that an officer when he is appointed by the concurrence of the Senate, and has friends in that body, may choose rather to risk his establishment on the favor of that branch, than rest it upon the discharge of his duties to the satisfaction [of] the executive branch, which is constitutionally authorized to inspect and control his conduct? And if it should happen that the officers connect themselves with the Senate, they may mutually support each other, and for want of efficacy reduce the power of the president to a mere vapor, in which case his responsibility would be annihilated, and the expectation of it unjust. The high executive officers, joined in cabal with the Senate, would lay the foundation of discord, and end in an assumption of the executive power, only to be removed by a revolution in the government. I believe no principle is more clearly laid down in the Constitution than that of responsibility. After premising this, I will proceed to an investigation of the merits of the question upon constitutional ground.

I have since the subject was last before the House, examined the Constitution with attention, and I acknowledge that it does not perfectly correspond with the ideas I entertained of it from the first glance. I am inclined to think that a free and systematic interpretation of the plan of government, will leave us less at liberty to abate the responsibility than gentlemen imagine. I have already acknowledged, that the powers of the government must remain as apportioned by the Constitution. But it may be contended, that where the Constitution is silent it becomes a subject of legislative discretion; perhaps, in the opinion of some, an argument in favor of the clause may be successfully brought forward on this ground: I however leave it for the present untouched.

By a strict examination of the Constitution on what appears to be its true principles, and considering the great departments of government in the relation they have to each other, I have my doubts whether we are not absolutely tied down to the construction declared in the bill. In the first section of the first article, it is said, that all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. In the second article it is affirmed, that the executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. In the third article it is declared, that the judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme court, and in such inferior courts as Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. I suppose it will be readily admitted, that so far as the Constitution has separated the power of these great departments, it would be improper to combine them together, and so far as it has left any particular department in the entire possession of the powers incident to that department, I conceive we ought not to qualify them farther than they are qualified by the Constitution. The legislative powers are vested in Congress, and are to be exercised by them uncontrolled by any other department, except the Constitution has qualified it otherwise. The Constitution has qualified the legislative power by authorizing the president to object to any act it may pass, requiring, in this case two-thirds of both houses to concur in making a law; but still the absolute legislative power is vested in Congress with this qualification alone.

The Constitution affirms, that the executive power shall be vested in the president: Are there exceptions to this proposition? Yes, there are. The Constitution says that, in appointing to office, the Senate shall be associated with the president, unless in the case of inferior officers, when the law shall otherwise direct. Have we a right to extend this exception? I believe not. If the Constitution has invested all executive power in the president, I venture to assert, that the legislature has no right to diminish or modify his executive authority.

The question now resolves itself into this, Is the power of displacing [an appointed official] an executive power? I conceive that if any power whatsoever is in its nature executive it is the power of appointing, overseeing, and controlling those who execute the laws. If the Constitution had not qualified the power of the president in appointing to office, by associating the Senate with him in that business, would it not be clear that he would have the right by virtue of his executive power to make such appointments? Should we be authorized, in defiance of that clause in the Constitution – “The executive power shall be vested in a president,” to unite the Senate with the president in the appointment to office? I conceive not. If it is admitted we should not be authorized to do this, I think it may be disputed whether we have a right to associate them in removing persons from office, the one power being as much of an executive nature as the other, and the first only is authorized by being excepted out of the general rule established by the Constitution, in these words, “the executive power shall be vested in the president.”

The judicial power is vested in a supreme court, but will gentlemen say the judicial power can be placed elsewhere, unless the Constitution has made an exception? The Constitution justifies the Senate in exercising a judiciary power in determining on impeachments: But can the judicial power be farther blended with the powers of that body? They cannot. I therefore say it is incontrovertible, if neither the legislative nor judicial powers are subjected to qualifications, other than those demanded in the Constitution, that the executive powers are equally unabateable as either of the other; and inasmuch as the power of removal is of an executive nature, and not affected by any constitutional exception, it is beyond the reach of the legislative body.

If this is the true construction of this instrument, the clause in the bill is nothing more than explanatory of the meaning of the Constitution, and therefore not liable to any particular objection on that account. If the Constitution is silent, and it is a power the legislature have a right to confer, it will appear to the world, if we strike out the clause, as if we doubted the propriety of vesting it in the President of the United States. I therefore think it best to retain it in the bill.

Madison’s letter to Edmund Pendleton, June 21, 1789

…For some time past I have been obliged to content myself with inclosing you the newspapers. In general they give, tho’ frequently erroneous and sometimes perverted, yet on the whole, fuller accounts of what is going forward than could be put into a letter. The papers now covered contain a sketch of a very interesting discussion which consumed [a] great part of the past week. The Constitution has omitted to declare expressly by what authority removals from office are to be made. Out of this silence four constructive doctrines have arisen.

- That the power of removal may be disposed of by the legislative discretion. To this it is objected that the legislature might then confer it on themselves, or even on the House of Representatives which could not possibly have been intended by the Constitution.

- That the power of removal can only be exercised in the mode of impeachment. To this the objection is that it would make officers of every description hold their places during good behavior, which could have still less been intended.

- That the power of removal is incident to the power of appointment. To this the objections are that it would require the constant session of the Senate, that it extends the mixture of legislative and executive power, that it destroys the responsibility of the president, by enabling a subordinate executive officer to entrench himself behind a party in the Senate, and destroys the utility of the Senate in their legislative and judicial characters, by involving them too much in the heats and cabals inseparable from questions of a personal nature; in fine that it transfers the trust in fact from the president who being at all times impeachable as well as every fourth year eligible by the people at large, may be deemed the most responsible member of the government, to the Senate who from the nature of that institution, is and was meant after the judiciary and in some respects without that exception to be the most unresponsible[1] branch of the Government.

- That the executive power being in general terms vested in the president, all power of an executive nature, not particularly taken away must belong to that department, that the power of appointment only being expressly taken away, the power of removal so far as it is of an executive nature must be reserved. In support of this construction it is urged that exceptions to general positions are to be taken strictly, and that the axiom relating to the separation of the legislative and executive functions ought to be favored. To this are objected the principle on which the third construction is founded, and the danger of creating too much influence in the executive magistrate.

The last opinion has prevailed, but is subject to various modifications, by the power of the legislature to limit the duration of laws creating offices, or the duration of the appointments for filling them, and by the power over the salaries and appropriations. In truth the legislative power is of such a nature that it scarcely can be restrained either by the Constitution or by itself. And if the federal government should lose its proper equilibrium within itself, I am persuaded that the effect will proceed from the encroachments of the legislative department. If the possibility of encroachments on the part of the executive or the Senate were to be compared, I should pronounce the danger to lie rather in the latter than the former. The mixture of legislative, executive and judiciary authorities lodged in that body, justifies such an inference; at the same [time] I am fully in the opinion, that the numerous and immediate representatives of the people, composing the other House, will decidedly predominate in the Government.

. . .

- 1. unresponsive to or least swayed by current public opinion

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.