No related resources

Introduction

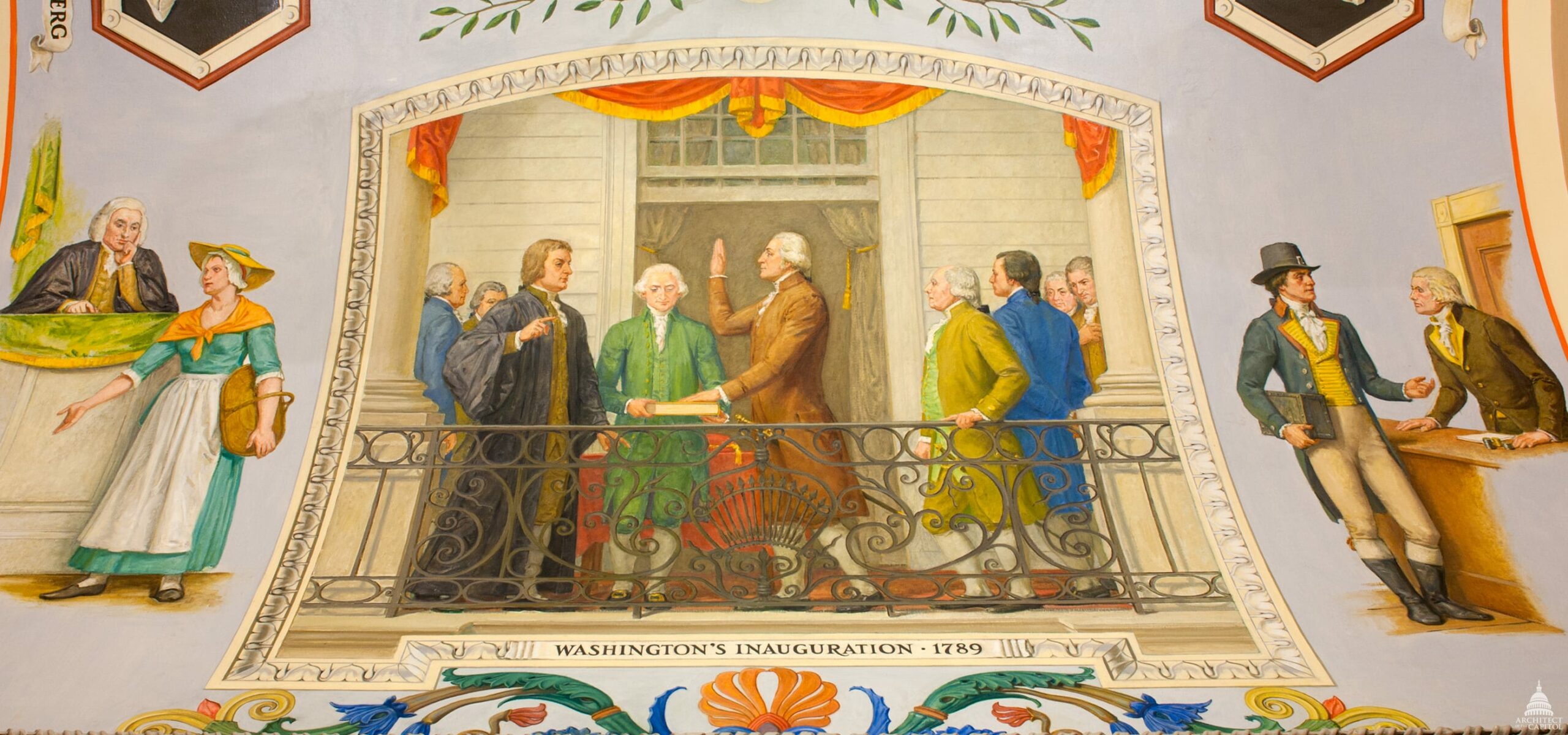

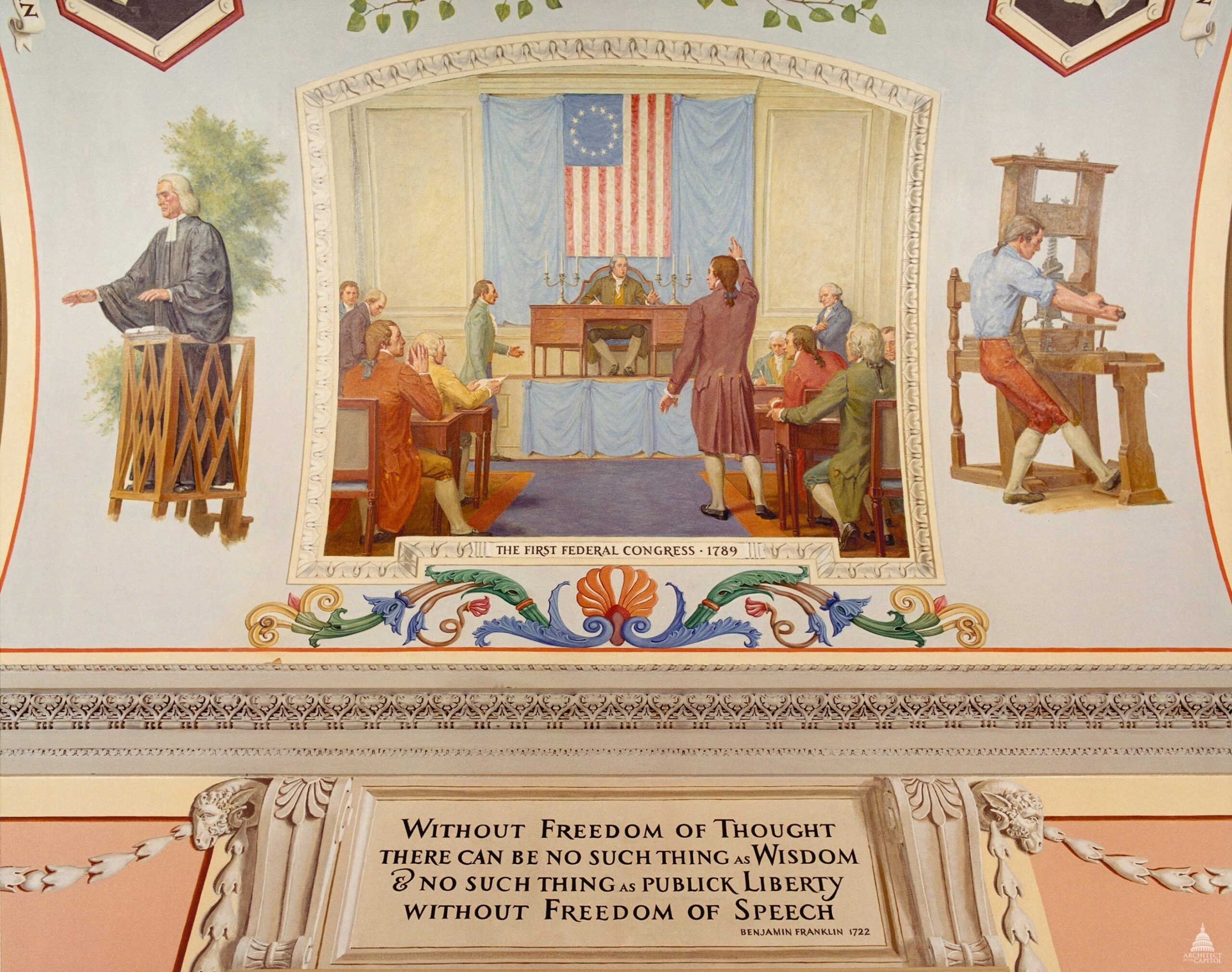

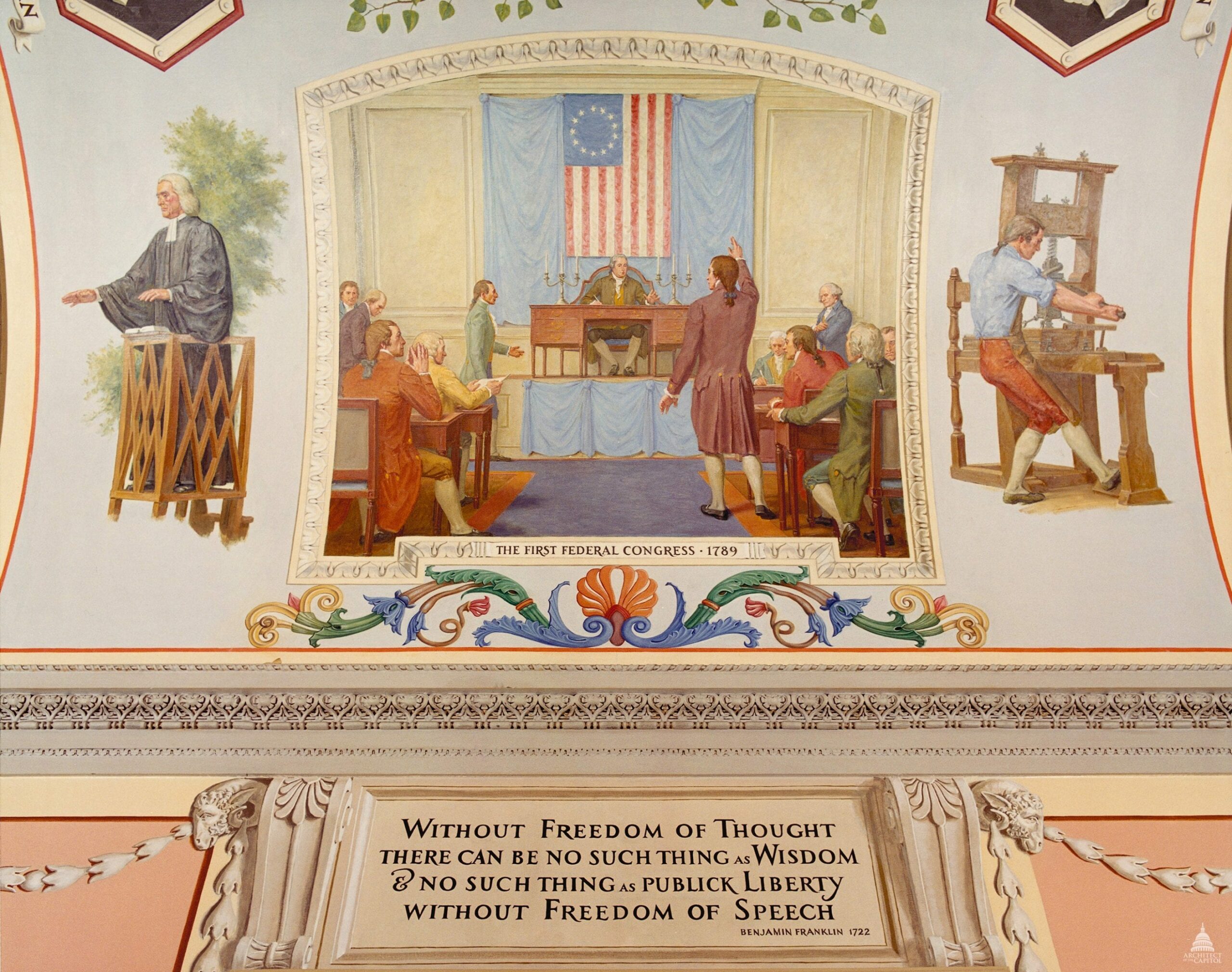

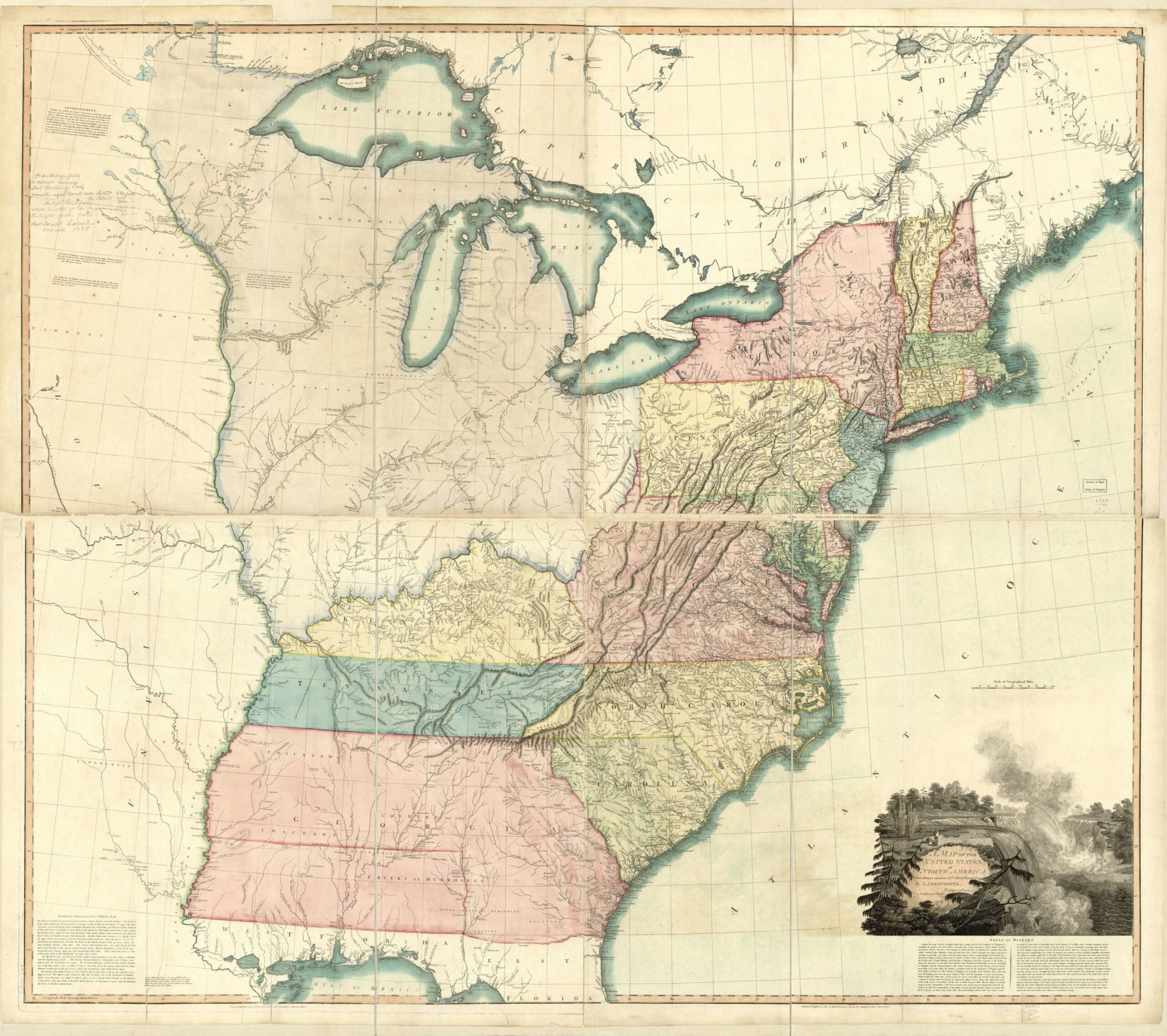

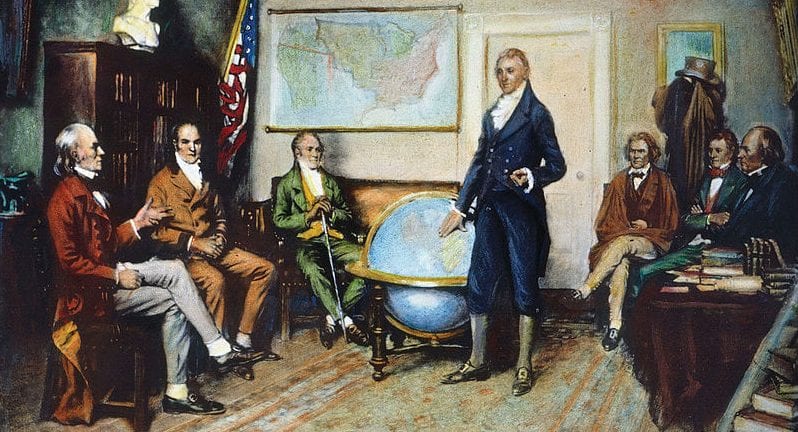

The Constitution clearly defines the power of appointment: “and [the president] shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the supreme Court, and all other officers of the United States, whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by law: but the Congress may by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers, as they think proper, in the president alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments” (Article II, section 2). However, the Constitution does not make it equally clear who has the power to remove subordinate executive officers. The absence of an express provision for removal gave rise to an extended debate in the First Congress when members took up the task of creating the initial cabinet offices for the government. The selection below includes selections from the debates in the House of Representatives in 1789 over the creation of the secretary of foreign affairs.

The members of the First Congress divided into four camps over the issue of removal. The “impeachment” camp argued that because impeachment was the only mode of removal expressly stated in the Constitution, removals would have to follow the procedures outlined for impeachment. A second group argued that because the appointment of superior officers required nomination by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, those officers could be removed only by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate. A third, “congressional delegation,” camp argued that the creation of an executive office was a legislative act, and therefore any determination of who would exercise the removal power belonged to Congress. Within this third position were two subdivisions: members who believed that Congress should retain the power to remove the secretary of foreign affairs, and those who believed Congress should “delegate” the power to the president for this particular office. Finally, the “executive power theory” camp argued that the removal power was an inherently executive power and belonged to the president alone by virtue of the vesting clause: “The executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States.”

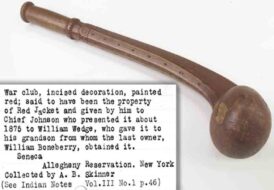

Annals of Congress 1789 (May–June 1789), 387–394, 473–475, 481, 508, 515–516, 521, 600–601, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llac&fileName=001/llac001.db&recNum=118.

[May 19, 1789]

The committee [of the Whole] proceeded to the discussion of the power of the president to remove [the secretary of foreign affairs].

Mr. Smith1 said, he had doubts about whether the officer could be removed by the president. He apprehended he could only be removed by an impeachment before the Senate, and that, being once in office, he must remain there until convicted upon impeachment. . . .

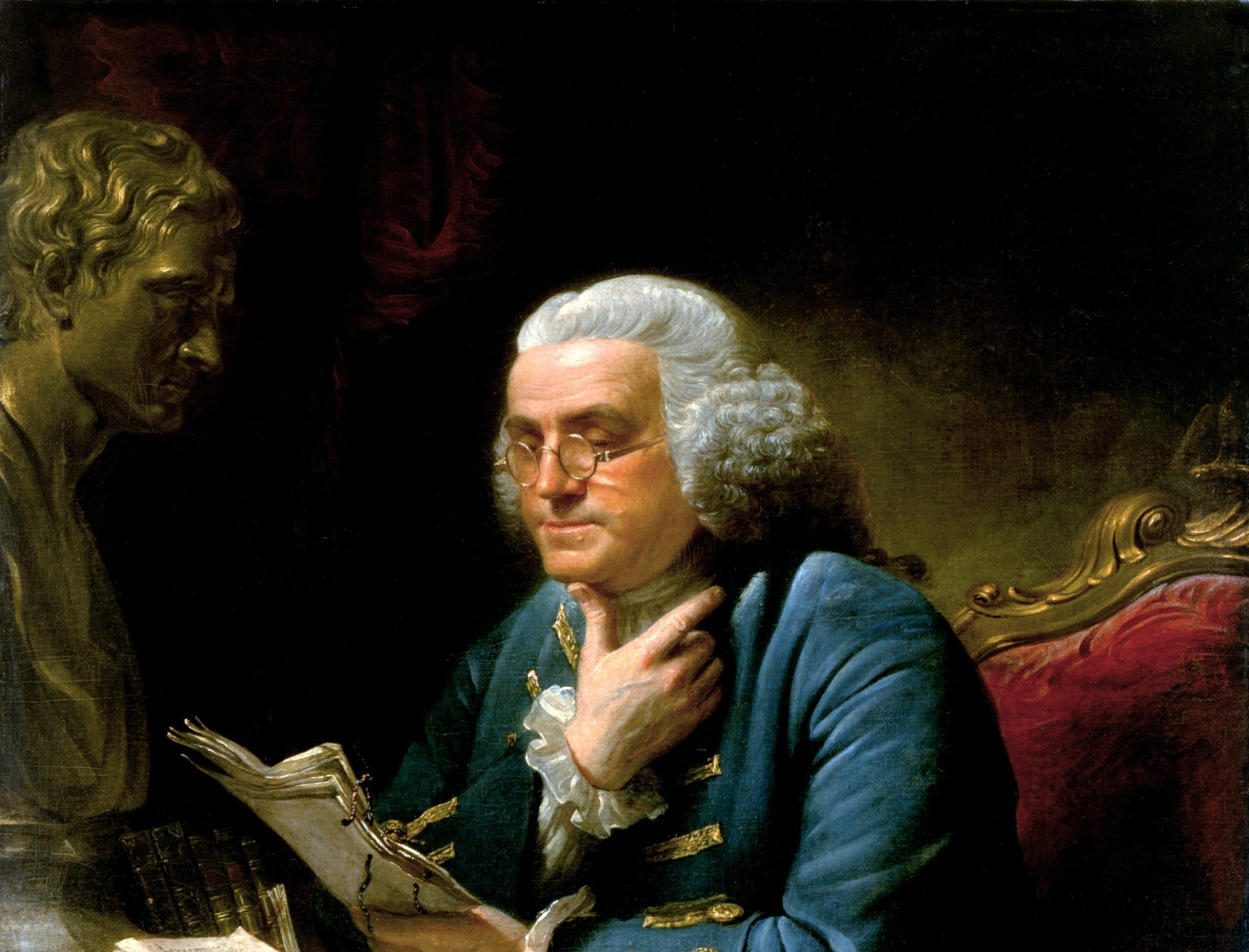

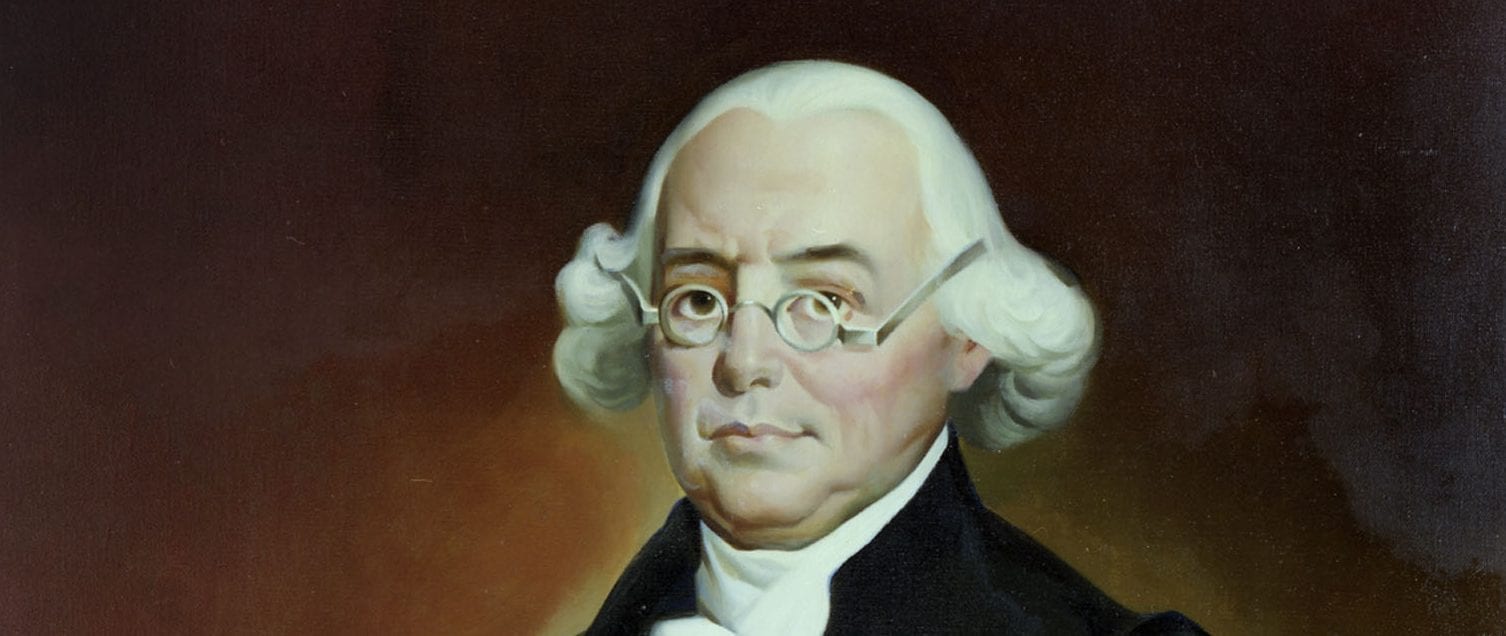

Mr. Madison.2 Did not concur with the gentleman in his interpretation of the Constitution. What said he would be the consequence of such construction? It would in effect establish every officer of the government on the firm tenure of good behavior, not the heads of departments only, but all the inferior officers of those departments would hold their offices during good behavior, and that to be judged of by one branch of the legislature only on the impeachment of the other. . . .

I think it absolutely necessary that the president should have the power of removing from office; it will make him, in a peculiar manner, responsible for their conduct, and subject him to impeachment himself, if he suffers them to perpetrate with impunity high crimes or misdemeanors against the United States, or neglects to superintend their conduct, so as to check their excesses. On the constitutionality of the declaration I have no manner of doubt. . . .

It is one of the most prominent features of the Constitution, a principle that pervades the whole system, that there should be the highest possible degree of responsibility in all the executive officers thereof; anything therefore which tends to lessen this responsibility is contrary to its spirit and intention, and unless it is saddled upon us expressly by the letter of that work, I shall oppose the admission of it into any act of the legislature. Now, if the heads of the executive departments are subjected to removal by the president alone, we have in him security for the good behavior of the officer: If he does not conform to the judgment of the president, in doing the executive duties of his office, he can be displaced; this makes him responsible to the great executive power, and makes the president responsible to the public for the conduct of the person he has nominated and appointed to aid him in the administration of his department; but if the president shall join in a collusion with this officer, and continue a bad man in office, the case of impeachment will reach the culprit, and drag him forth to punishment. But if you take the other construction, and say he shall not be displaced, but by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, the president is no longer answerable for the conduct of the officer; all will depend upon the Senate. You here destroy a real responsibility without obtaining even the shadow; for no gentleman will pretend to say, the responsibility of the Senate can be of such a nature as to afford substantial security. But why, it may be asked, was the Senate joined with the president in appointing to office, if they have no responsibility? I answer, merely for the sake of advising, being supposed, from their nature, better acquainted with the characters of the candidates than an individual; yet even here the president is held to the responsibility he nominates, and with their consent appoints; no person can be forced upon him as an assistant by any other branch of the government. . . .

[June 16, 1789]

The House then resolved itself into a Committee of the Whole on the bill for establishing an executive department, to be denominated the Department of Foreign Affairs. . . .The first clause . . . had these words, “To be removable from office by the president of the United States.”

Mr. White.3 The Constitution gives the president the power of nominating and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, appointing to office. As I conceive the power of appointing and dismissing to be united in their natures, and a principle that never was called in question in any government, I am averse to that part of the clause which subjects the secretary of foreign affairs to be removed at the will of the president. . . .

I take the liberty of reviving the motion made in the Committee of the Whole, for striking out these words: “to be removable from office by the president of the United States.”

Mr. Smith. The gentleman has anticipated me in his motion; I am clearly in sentiment with him that the words ought to go out. . . .

I would premise that one of these two ideas are just: either that the Constitution has given the president the power of removal, and therefore it is nugatory to make the declaration here; or that it has not given the power to him, and therefore it is improper to make an attempt to confer it upon him. If it is not given to him by the Constitution, but belongs jointly to the president and Senate, we have no right to deprive the Senate of their constitutional prerogative. . . .

[Mr. Smith then quoted from Federalist 77, in which Alexander Hamilton declared that the Senate would have to concur in removals from office, as in the case of appointments.]

Here this author lays it down, that there can be no doubt of the power of the Senate in the business of removal. Let this be as it may, I am clear that the president alone has not the power. Examine the Constitution; the powers of the several branches of government are there defined; the president has particular powers assigned him; the judiciary have in like manner powers assigned them; but you will find no such power as removing from office given to the president. I call upon gentlemen to show me where it is said that the president shall remove from office. I know they cannot do it. Now, I infer from this, that, as the Constitution has not given the president the power of removability, it meant that he should not have that power; and this inference is supported by that clause in the Constitution which provides that all civil officers of the United States shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and on conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors. Here is a particular mode prescribed for removing; and if there is no other mode directed, I contend that the Constitution contemplated only this mode. . . .

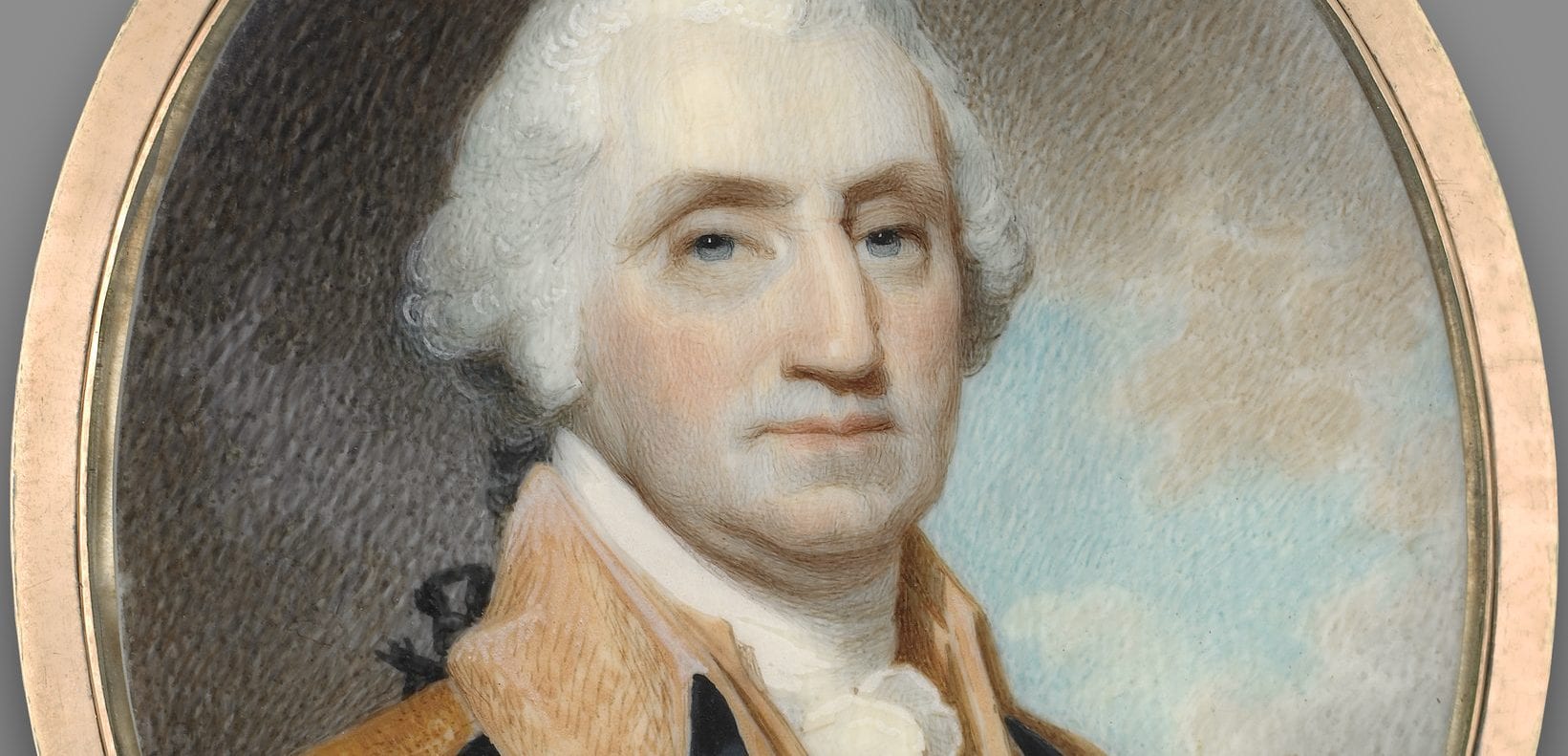

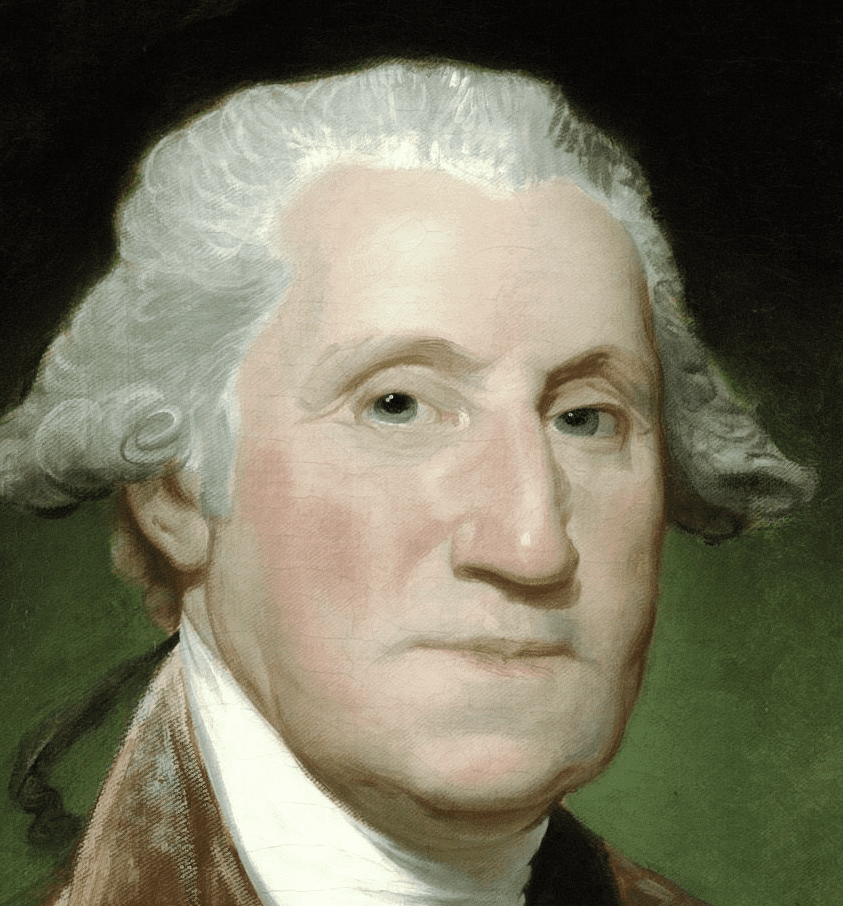

I imagine, sir, we are declaring a power in the president which may hereafter be greatly abused; for we are not always to expect a chief magistrate in whom such entire confidence can be placed as in the present. Perhaps gentlemen are so much dazzled with the splendor of the virtues of the present president4 as not to see into futurity. . . .

Mr. Madison. . . . By a strict examination of the Constitution, on what appears to be its true principles, and considering the great departments of the government in the relation they have to each other, I have my doubts whether we are not absolutely tied down to the construction declared in the bill. In the first section of the first article, it is said that all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. In the second article, it is affirmed that the executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States. . . .

The Constitution affirms that the executive power shall be vested in the president. Are there exceptions to this proposition? Yes, there are. The Constitution says that in appointing to office, the Senate shall be associated with the president, unless in the case of inferior officers, when the law shall otherwise direct. Have we a right to extend this exception? I believe not. If the Constitution has invested all executive power in the president, I venture to assert that the legislature has no right to diminish or modify his executive authority.

The question now resolves itself into this: Is the power of displacing an executive power? I conceive that if any power whatsoever is in its nature executive, it is the power of appointing, overseeing, and controlling those who execute the laws. If the Constitution had not qualified the power of the president in appointing to office, by associating the Senate with him in that business, would it not be clear that he would have the right, by virtue of his executive power, to make such appointment? . . .

If this is the true construction of this instrument, the clause in the bill is nothing more than explanatory of the meaning of the Constitution, and therefore not liable to any particular objection on that account. If the Constitution is silent, and it is a power the legislature have a right to confer, it will appear to the world, if we strike out the clause, as if we doubted the propriety of vesting it in the president of the United States. I therefore think it best to retain it in the bill.

[June 17, 1789]

Mr. Jackson.5. . .The gentleman from New York (Mr. Lawrence)6 contends that the president appoints, and, therefore, he ought to remove. I shall agree to give him the same power in cases of removal that he has in appointing; but nothing more. . . .I am the friend of an energetic government; but while we are giving vigor to the executive arm, we ought to be careful not to lay the foundation of future tyranny. I think this power too great to be safely trusted in the hands of a single man, especially in the hands of a man who has so much constitutional power. . . .It is under this impression that I shall vote decidedly against the clause. . . .

Mr. Madison. . . .The decision that is at this time made, will become the permanent exposition of the Constitution; and on a permanent exposition of the Constitution will depend the genius and character of the whole government. . . .It is incumbent upon us to weigh with particular attention, the arguments which have been advanced in support of the various opinions with cautious deliberation. . . .

Several constructions have been put upon the Constitution relative to the point in question. The gentleman from Connecticut (Mr. Sherman)7 has advanced a doctrine which was not touched upon before. He seems to think (if I understood him rightly) that the power of displacing from office is subject to legislative discretion; because it having a right to create [an office], it may limit or modify as it thinks proper. I shall not say but at first view this doctrine may seem to have some plausibility. But when I consider that the Constitution clearly intended to maintain a marked distinction between the legislative, executive, and judicial powers of government, and when I consider that if the legislature has a power, such as contended for, they may subject and transfer at discretion powers from one department of our government to another. . .I own that I cannot subscribe to it.

Another doctrine, which has found very respectable friends, has been particularly advocated by the gentleman from South Carolina (Mr. Smith). It is this: when an officer is appointed by the president and Senate, he can only be displaced for malfeasance in his office by impeachment. I think this would give a stability to the executive department, so far as it may be described by the heads of departments, which is more incompatible with the genius of republican governments in general, and this Constitution in particular, than any doctrine which has yet been proposed. The danger to liberty, the danger of maladministration, has not yet been found to lie so much in the facility of introducing improper persons into office, as in the difficulty of displacing those who are unworthy of the public trust. . . .[Under this doctrine,] I shall be glad to know what security we have for the faithful administration of the government? Every individual, in the long chain which extends from the highest to the lowest link of the executive magistracy, would find a security in his situation which would relax his fidelity and promptitude in the discharge of his duty.

The doctrine, however, which seems to stand most in opposition to the principles I contend for, is that the power to annul an appointment is, in the nature of things, incidental to the power which makes the appointment. I agree that if nothing more was said in the Constitution than that the president, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, should appoint to office, there would be great force in saying that the power of removal resulted by a natural implication from the power of appointing. But there is another part of the Constitution, no less explicit than the one on which the gentleman’s doctrine is founded; it is that part which declares that the executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States. The association of the Senate with the president in [appointing officers] is an exception to this general rule; and exceptions to general rules, I conceive, are ever to be taken strictly. But there is another part of the constitution which inclines, in my judgment, to favor the construction I put upon it; the president is required to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. If the duty to see the laws faithfully executed be required at the hands of the executive magistrate, it would seem that it was generally intended he should have that species of power which is necessary to accomplish that end. . . .

My conclusion from these reflections is that it will be constitutional to retain the clause; that it expresses the meaning of the Constitution as must be established by fair construction, and a construction which, upon the whole, not only consists with liberty, but is more favorable to it than any one of the interpretations that have been proposed. . . .

[June 22, 1789]

Mr. Benson8 moved to amend the bill, by altering the second clause, so as to imply the power of removal to be in the president [by inserting in another part of the bill] “whenever the said principal officer shall be removed from office by the president of the United States.”. . .

Mr. Benson declared, if he succeeded in this amendment, he would move to strike out the words in the first clause, “to be removable by the president,” which appeared somewhat like a grant [of removal power from Congress]. Now, the mode he took would evade that point, and establish a legislative construction of the Constitution. He also hoped this amendment would succeed in reconciling both sides of the House to the decision, and quieting the minds of gentlemen. …9

The question on the amendment proposed by Mr. Benson was taken by the yeas and nays [and passed, 30–18].

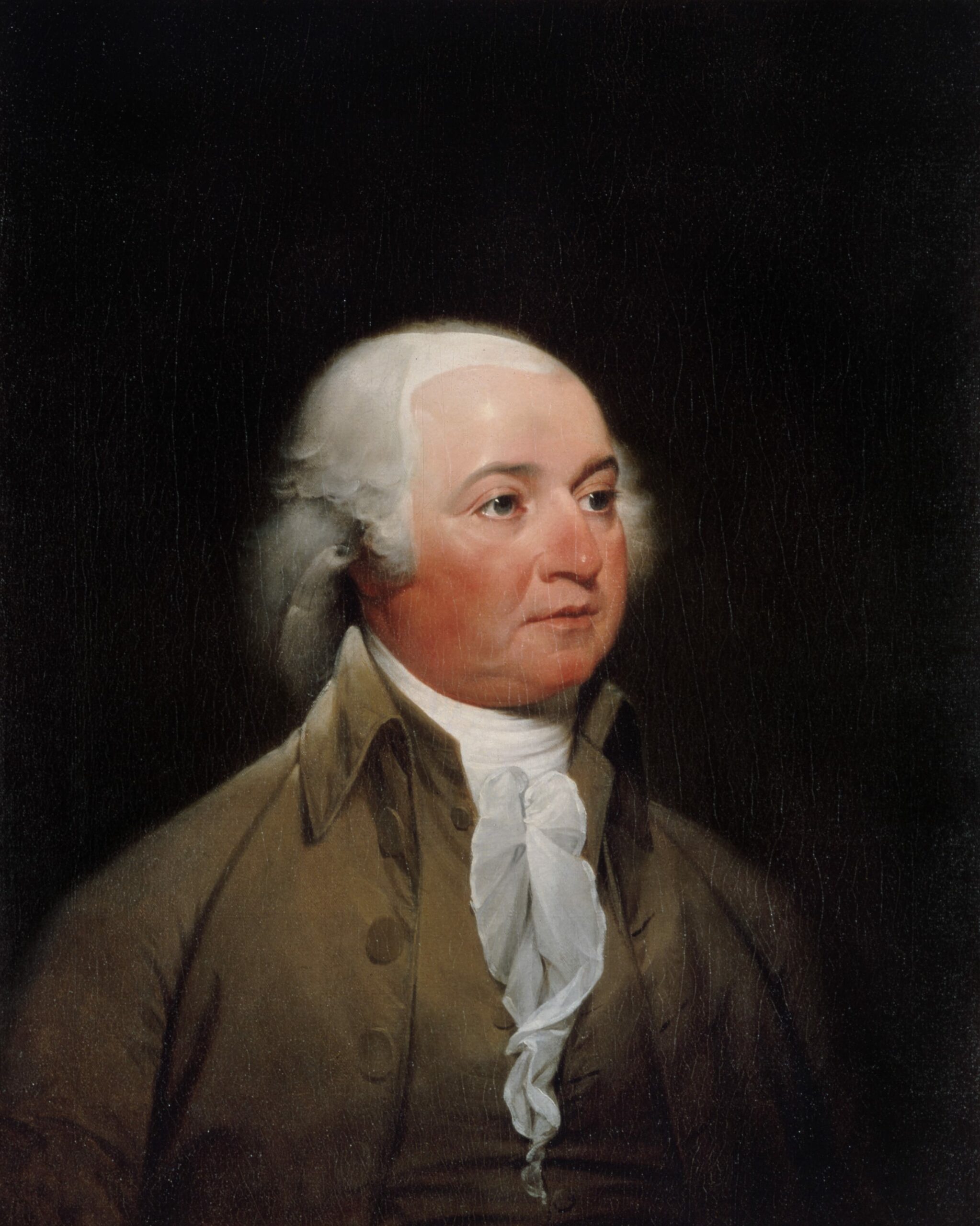

[The other part of Benson’s proposal, to strike the clause “to be removable by the president,” also passed, 31–19. The entire bill passed two days later, on June 24, 29–22. In the Senate, Vice President John Adams broke a tie vote to pass the bill.]

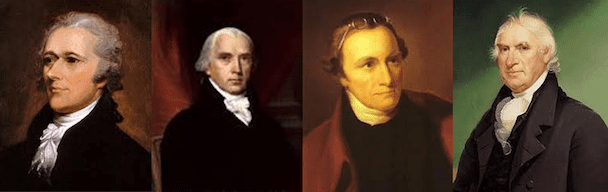

- 1. William Loughton Smith (1758–1812) was a member of the House of Representatives from South Carolina between 1789 and 1797.

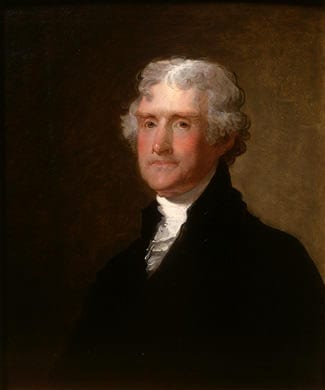

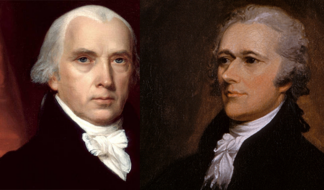

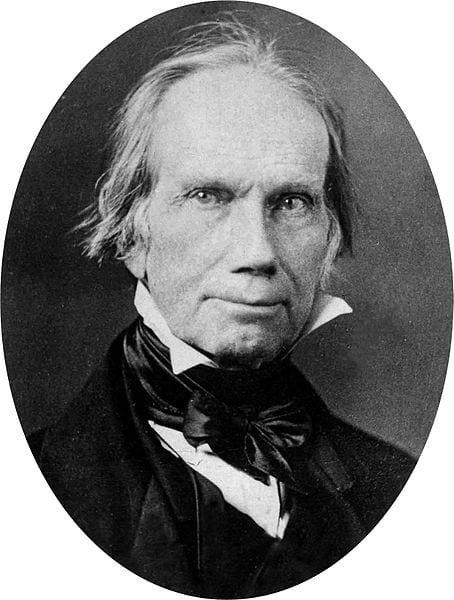

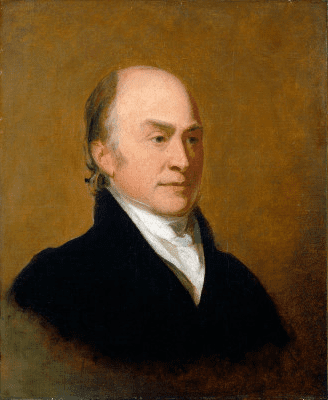

- 2. James Madison (1751–1836) was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia between 1789 and 1797.

- 3. Alexander White (1738–1804) was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia between 1789 and 1793.

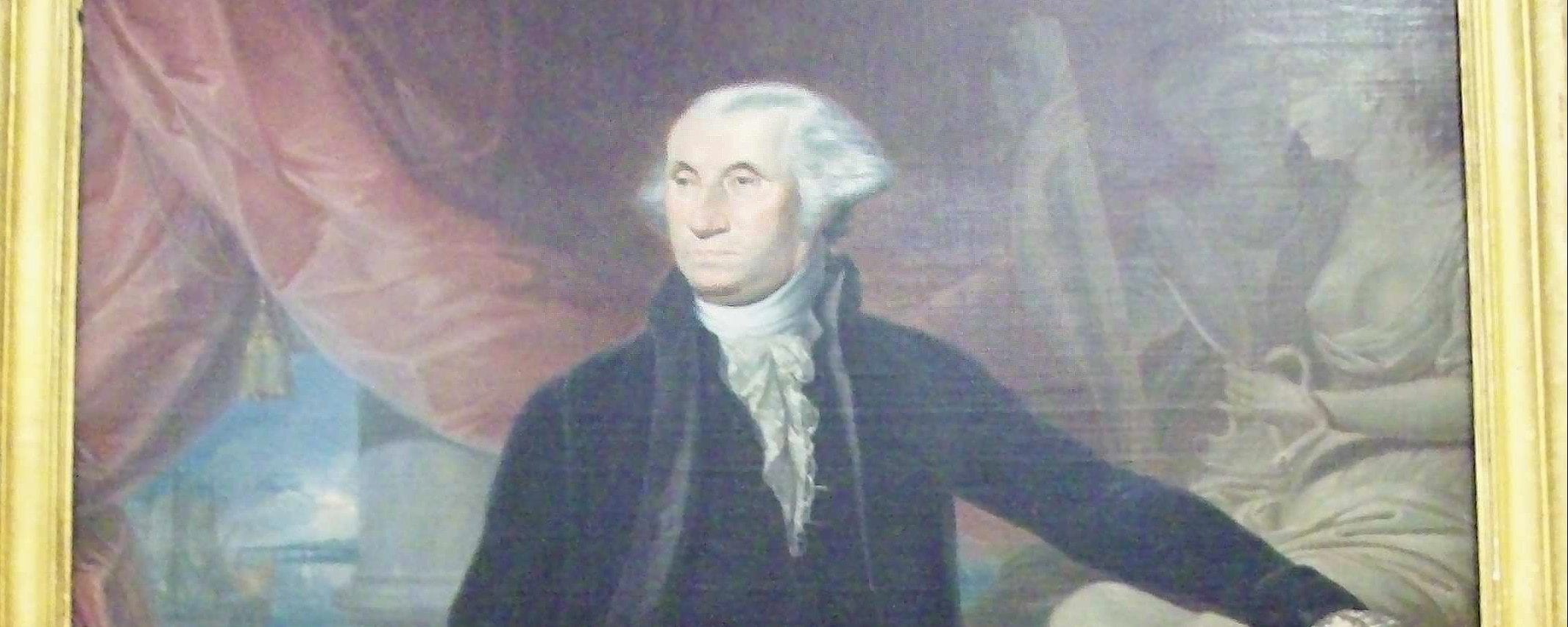

- 4. Referring to President George Washington.

- 5. James Jackson (1757–1806) represented Georgia in the House of Representatives between 1789 and 1791.

- 6. John Lawrence (1750–1810) represented New York in the House of Representatives between 1789 and 1793.

- 7. Roger Sherman (1721–1793) was a member of the House of Representatives from Connecticut between 1789 and 1793.

- 8. Egbert Benson (1746–1833) was a member of the House of Representatives from New York between 1789 and 1793.

- 9. It is important to note that this amendment attempted to gain the support of two groups: those who believed that the president inherently possessed the power to remove, and those who believed the legislature had the power to determine the removal but also believed that, in the case of the secretary of foreign affairs, the power should be granted by Congress to the president. In effect, the debate over whether Congress or the president controlled the removal power was ultimately unresolved by the First Congress.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.