No related resources

Introduction

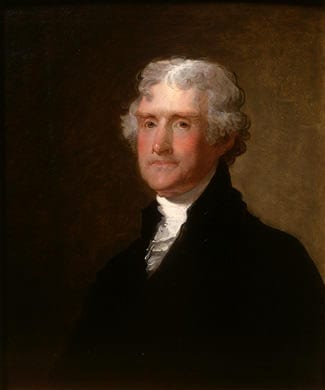

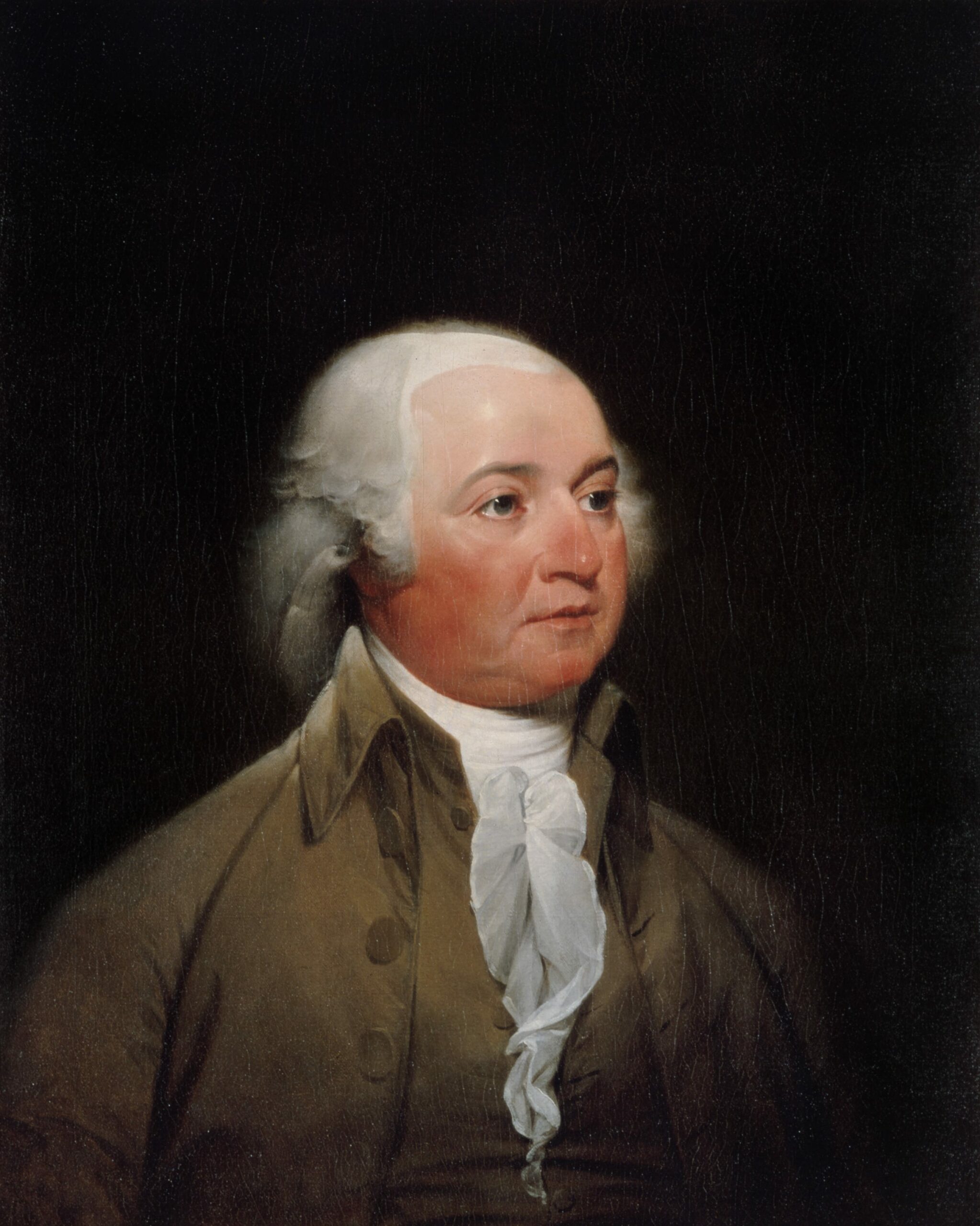

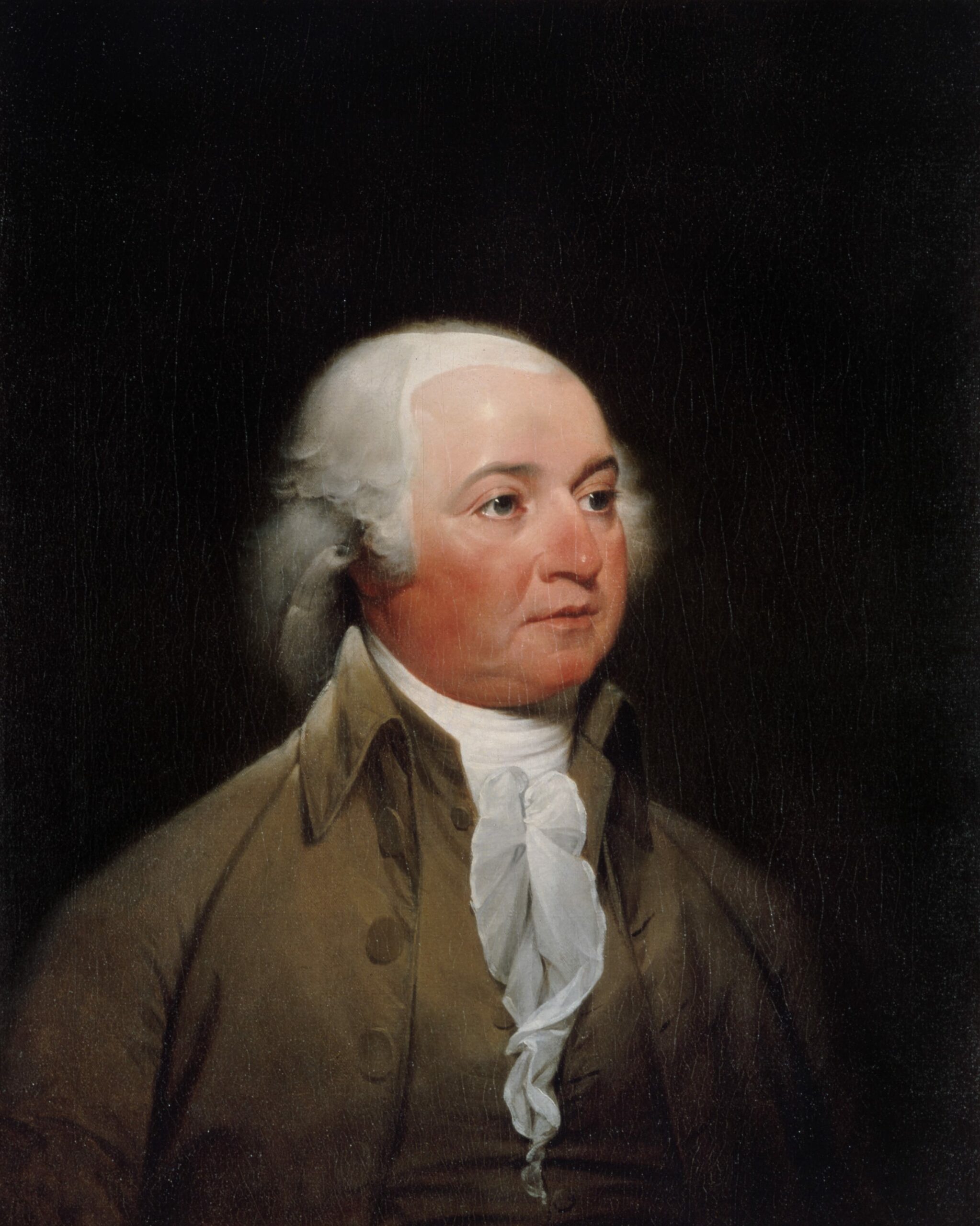

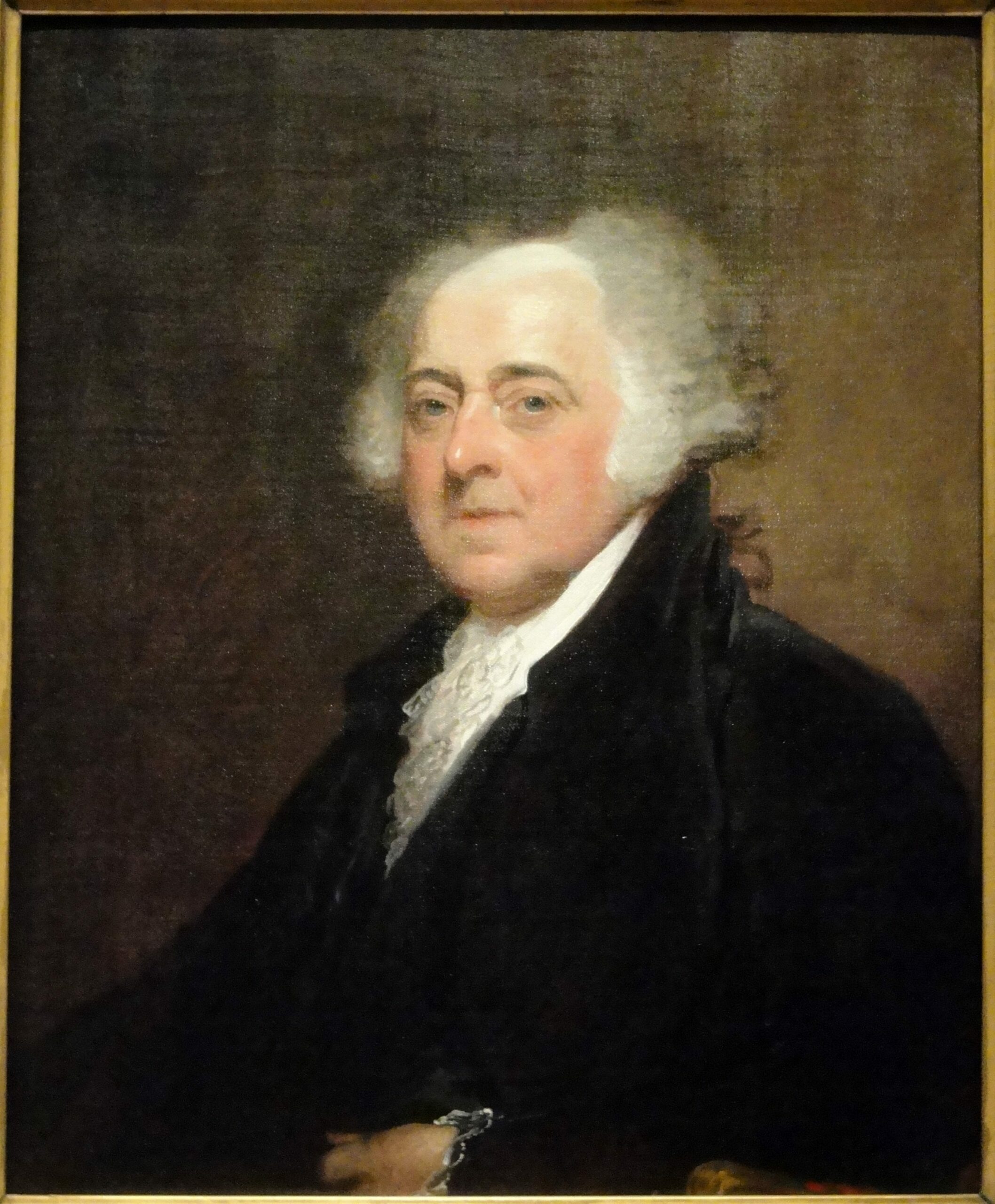

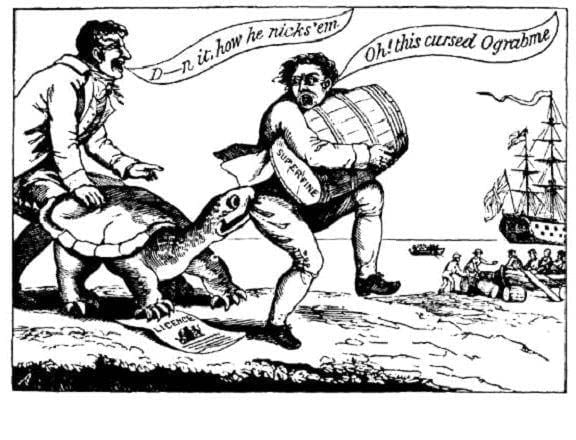

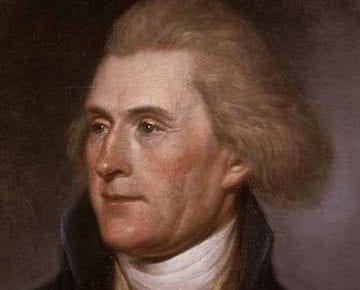

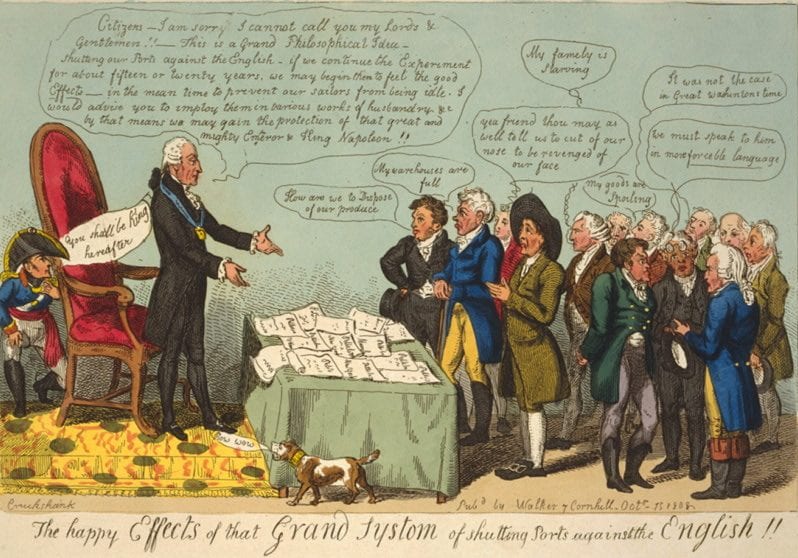

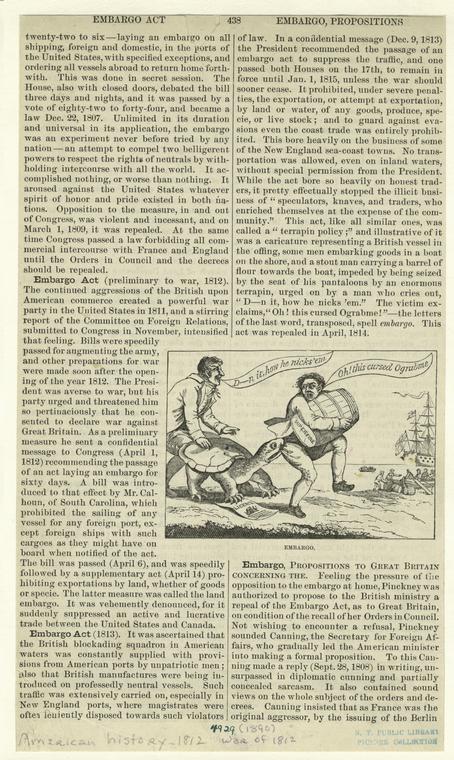

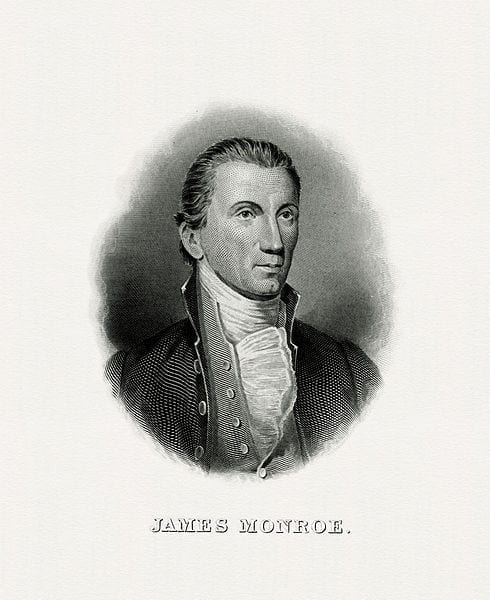

In the eyes of France, the Neutrality Proclamation and the Jay Treaty between the United States and Great Britain were proof that the United States had allied itself with Great Britain. In response, France began to harass American shipping on the high seas, seizing more than three hundred American ships in 1795 alone. John Adams’ victory over Thomas Jefferson in the election of 1796 only deepened the antipathy of the French toward the United States. By the time of Adams’ inauguration in March 1797, the two nations were close to war. The situation was so grave that Vice President–elect Thomas Jefferson observed that outgoing president George Washington was “fortunate to get off just as the bubble is bursting, leaving others to hold the bag.”

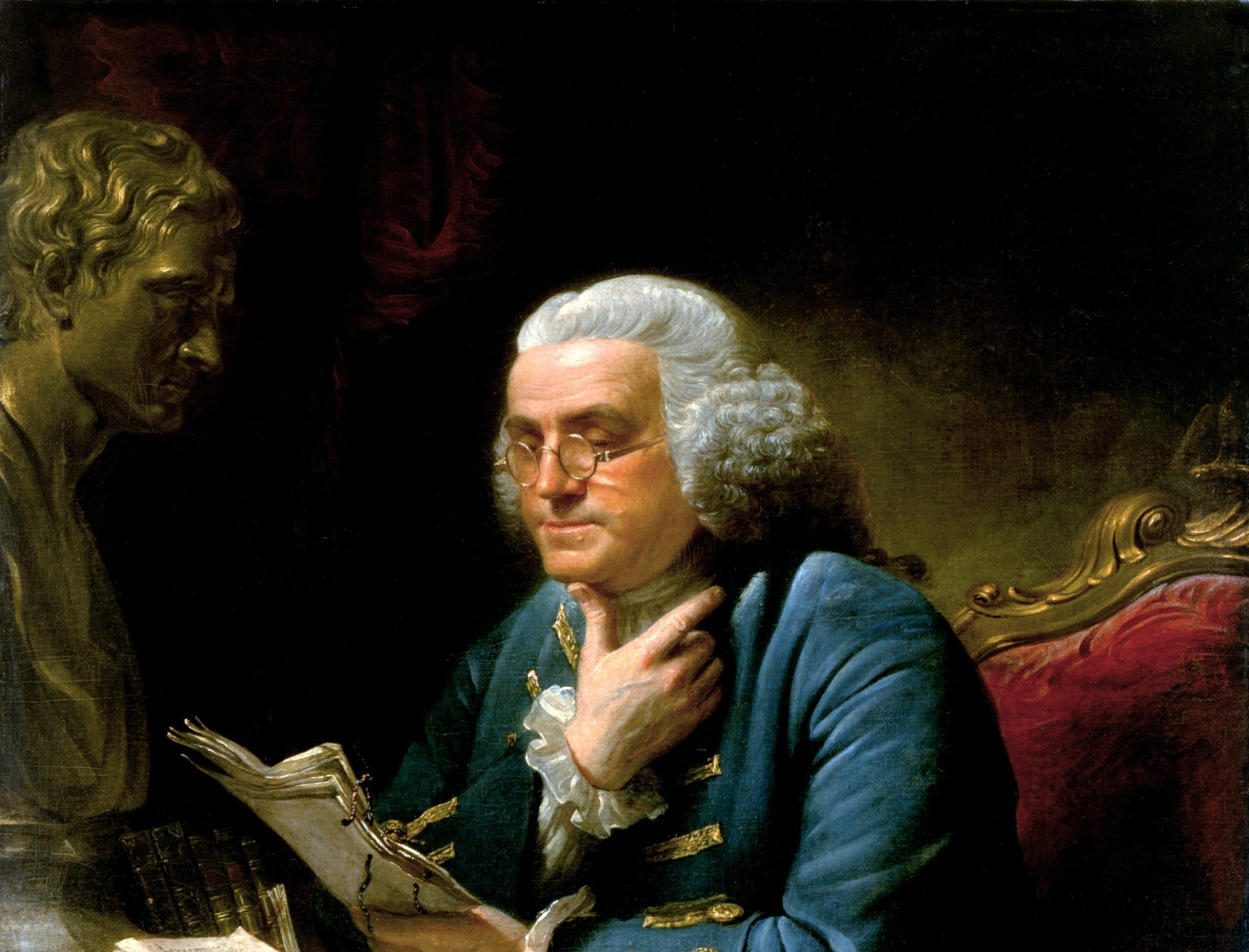

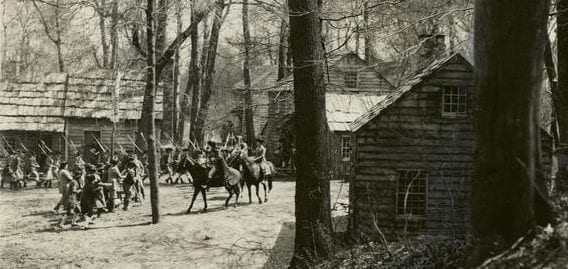

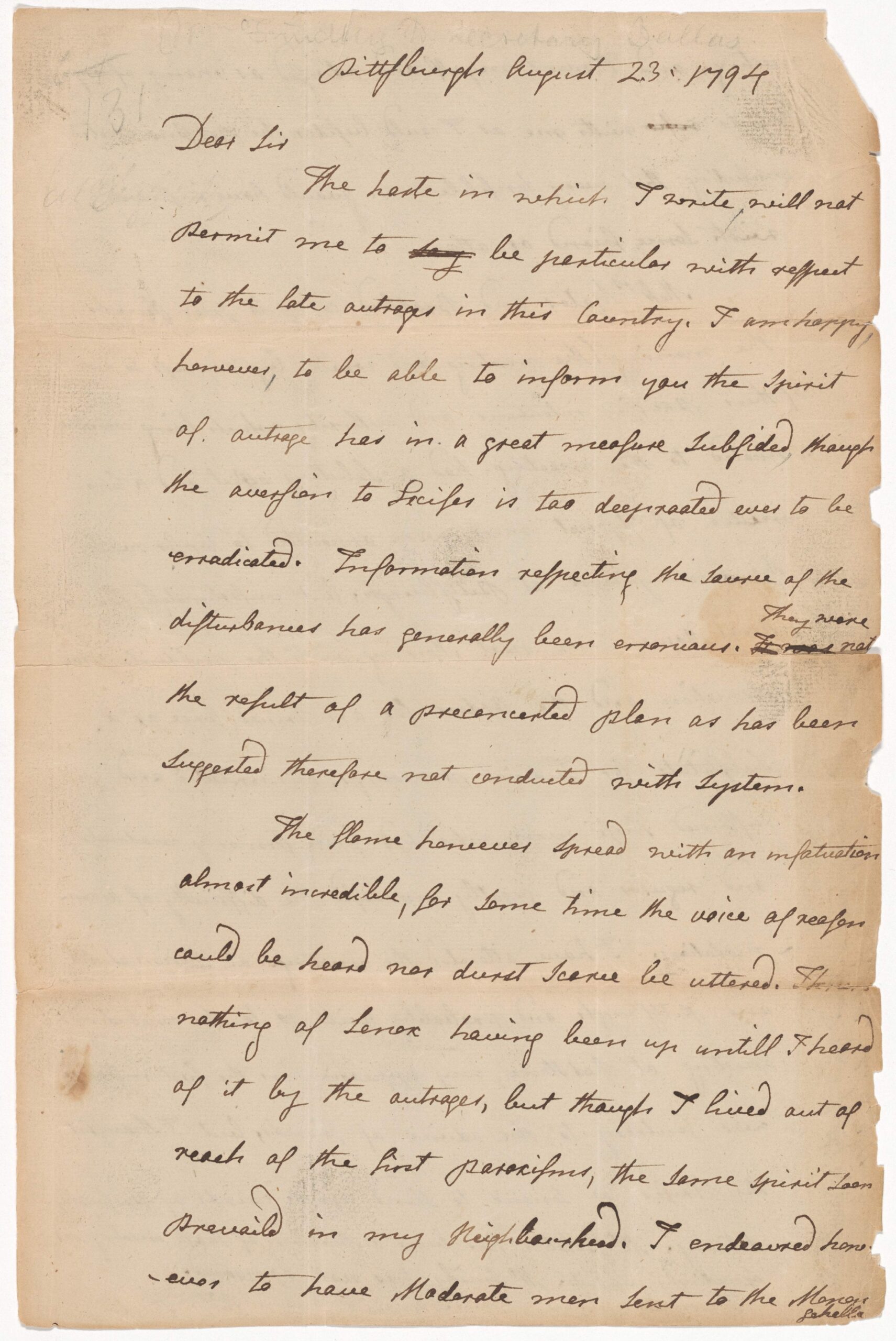

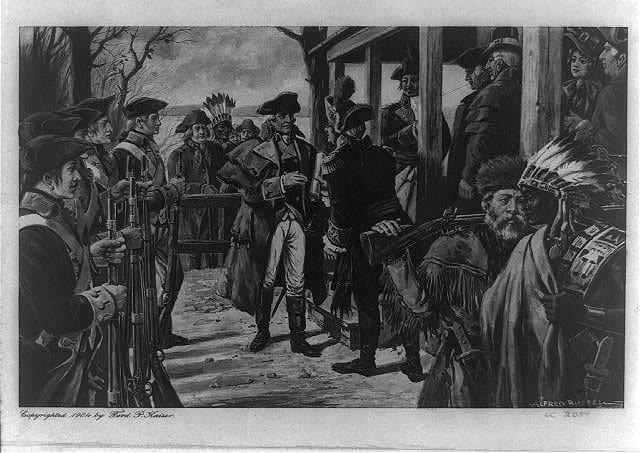

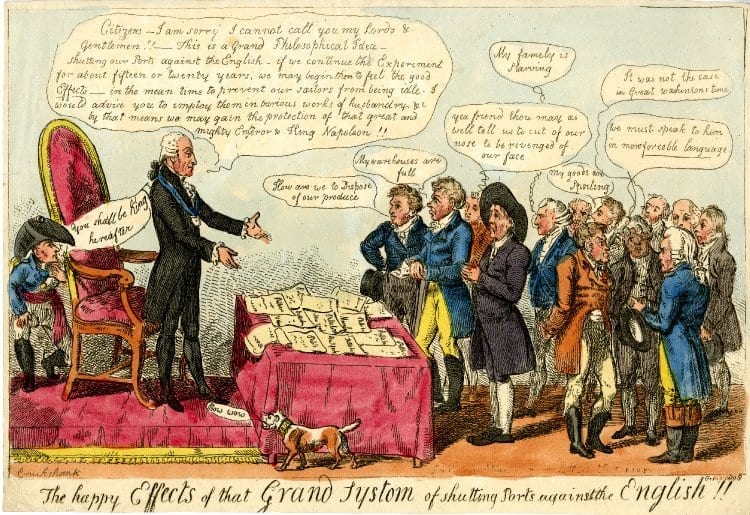

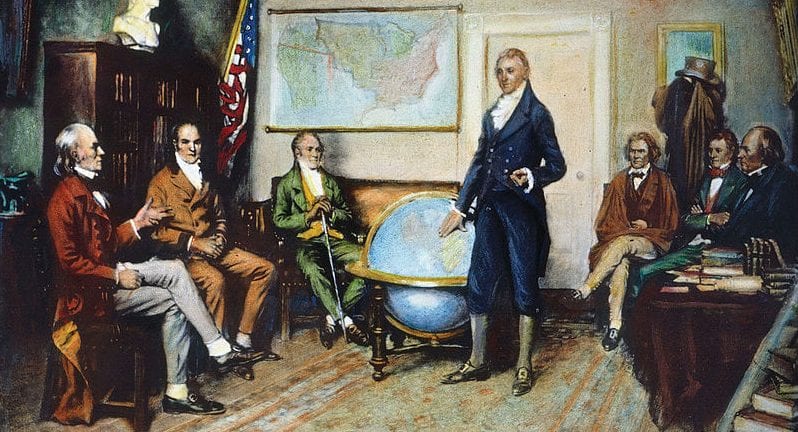

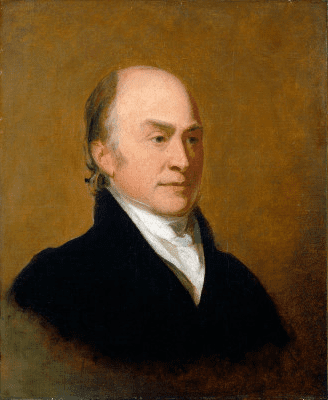

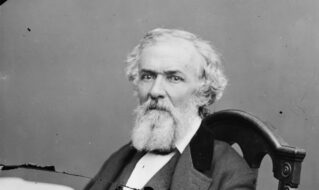

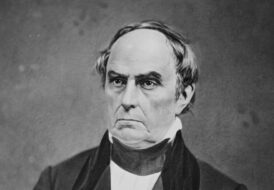

President Adams followed Washington’s neutrality policy and dispatched a negotiating team consisting of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (1746–1825), John Marshall (1755–1835), and Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814) to convince the government in Paris to accept America’s neutral status and restore some degree of comity between the two nations. Foreign Minister Talleyrand (1754–1838) rebuffed the delegation and referred them to three deputies whom the American diplomats identified in their dispatches as X, Y, and Z (respectively, Jean Hottinguer, Pierre Bellamy, and Lucien Hauteval). The three Frenchmen insisted that the Americans would have to pay bribes and arrange for a lucrative loan for the French government before negotiations could begin. When news of the “XYZ Affair” reached the United States, Americans were furious at this affront to their nation’s honor. John Adams began to talk openly about the likelihood of war and took to sporting a military uniform complete with a sword.

On April 3, 1798, President Adams, under attack from Democrat-Republicans for leading the nation into an unnecessary war with France, released several documents outlining the details of the extortion attempt from X, Y, and Z. A month later, with war fever at its height, the president called Congress back into session to deliver the following sober message while discussing the “indignities” directed toward the government of the United States.

Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 5th Congress, 1st session, 55–59, available at https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llac&fileName=007/llac007.db&recNum=23.

… [French conduct] evinces a disposition to separate the people of the United States from the government, to persuade them that they have different affections, principles, and interests from those of their fellow citizens whom they themselves have chosen to manage their common concerns, and thus to produce divisions fatal to our peace. Such attempts ought to be repelled with a decision which shall convince France and the world that we are not a degraded people, humiliated under a colonial spirit of fear and sense of inferiority, fitted to be the miserable instruments of foreign influence, and regardless of national honor, character, and interest.

I should have been happy to have thrown a veil over these transactions if it had been possible to conceal them; but they have passed on the great theater of the world, in the face of all Europe and America, and with such circumstances of publicity and solemnity that they cannot be disguised and will not soon be forgotten. They have inflicted a wound in the American breast. It is my sincere desire, however, that it may be healed. It is my sincere desire, and in this I presume I concur with you and with our constituents, to preserve peace and friendship with all nations; and believing that neither the honor nor the interest of the United States absolutely forbid the repetition of advances for securing these desirable objects with France, I shall institute a fresh attempt at negotiation, and shall not fail to promote and accelerate an accommodation on terms compatible with the rights, duties, interests, and honor of the nation. If we have committed errors, and these can be demonstrated, we shall be willing on conviction to redress them; and equal measures of justice we have a right to expect from France and every other nation. …

While we are endeavoring to adjust all our differences with France by amicable negotiation, the progress of the war in Europe, the depredations on our commerce, the personal injuries to our citizens, and the general complexion of affairs render it my indispensable duty to recommend to your consideration effectual measures of defense….

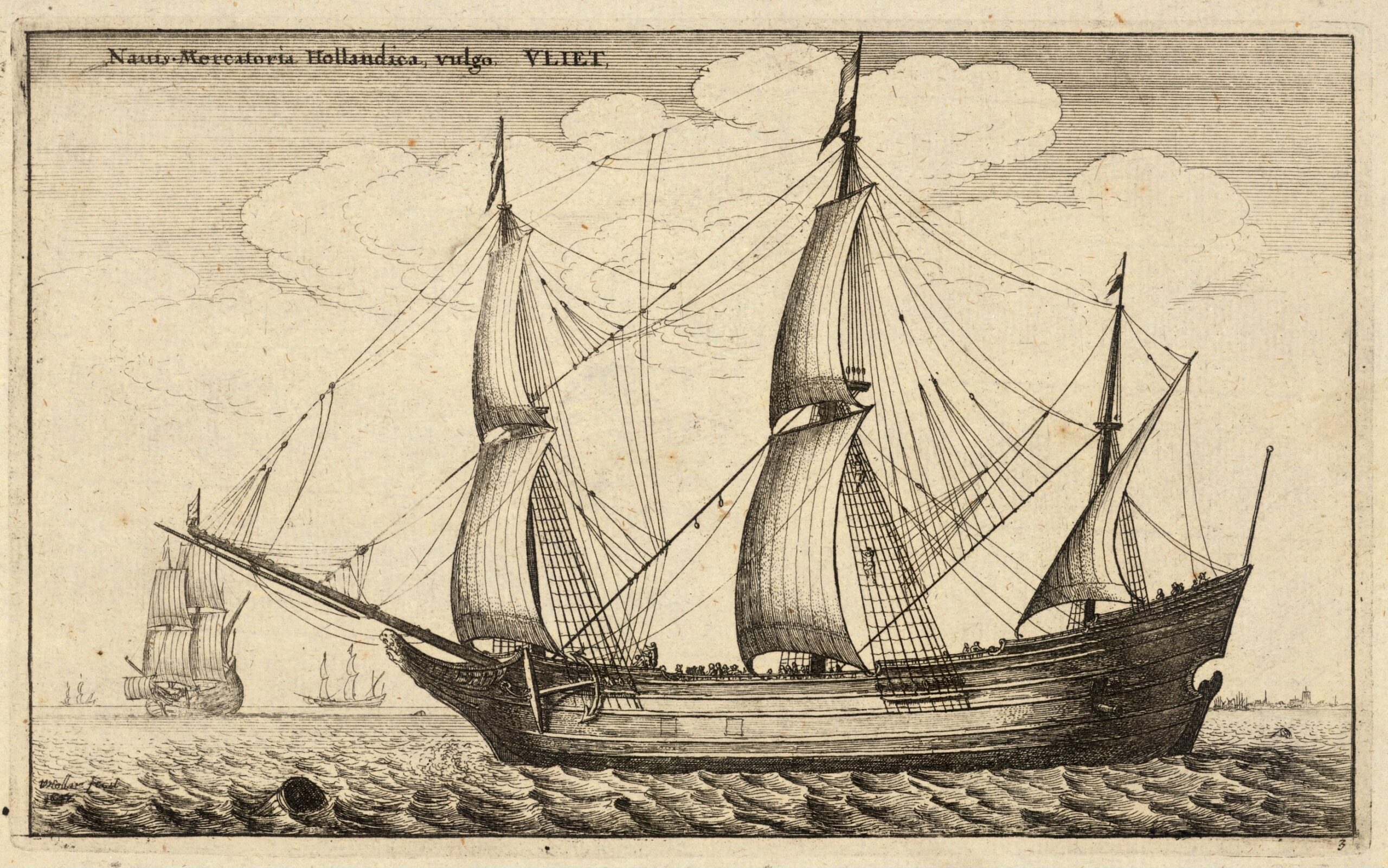

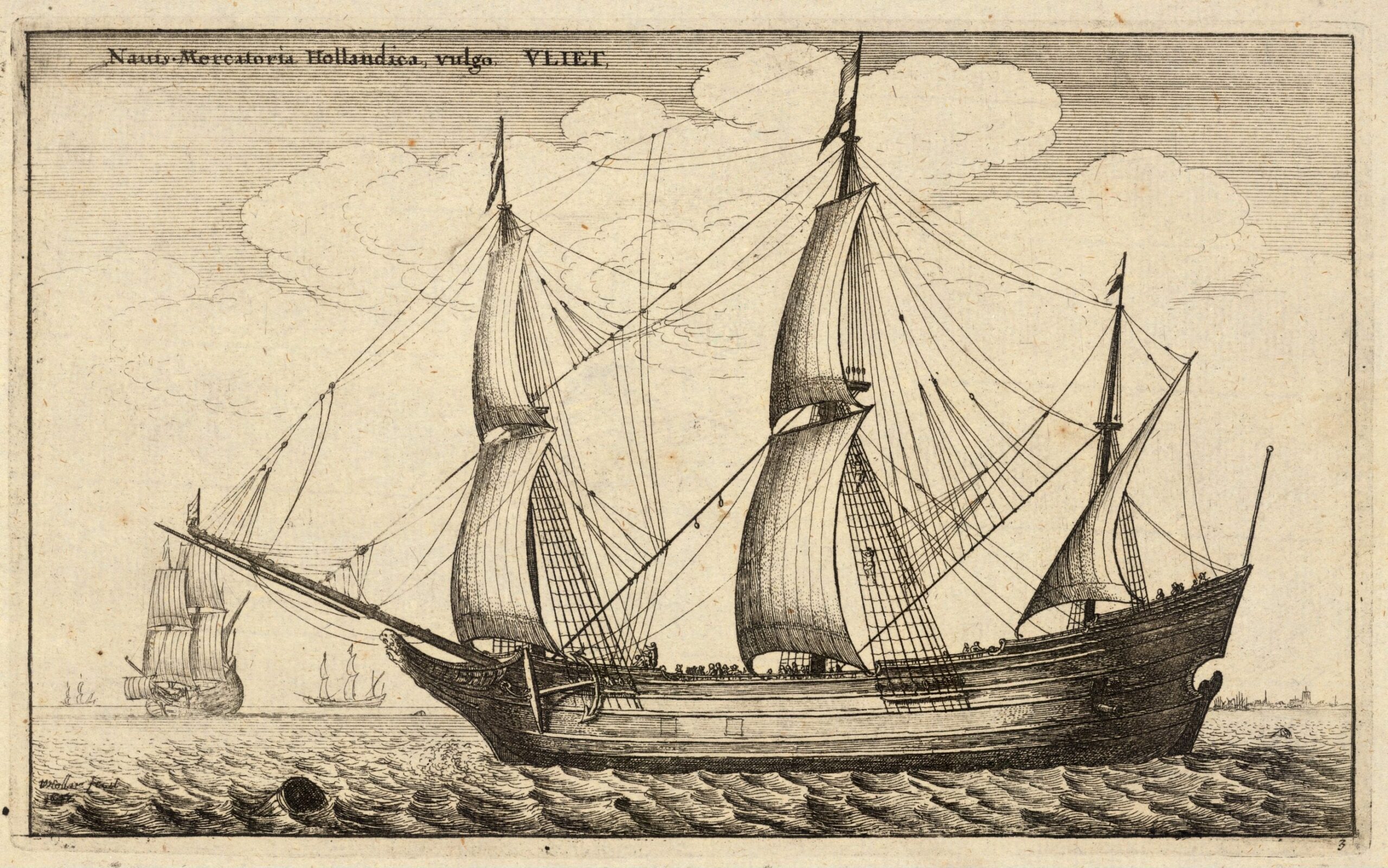

The naval establishment must occur to every man who considers the injuries committed on our commerce, the insults offered to our citizens, and the description of vessels by which these abuses have been practiced. As the sufferings of our mercantile and seafaring citizens cannot be ascribed to the omission of duties demandable, considering the neutral situation of our country, they are to be attributed to the hope of impunity arising from a supposed inability on our part to afford protection. To resist the consequences of such impressions on the minds of foreign nations and to guard against the degradation and servility which they must finally stamp on the American character is an important duty of government.

A naval power, next to the militia, is the natural defense of the United States. The experience of the last war would be sufficient to show that a moderate naval force, such as would be easily within the present abilities of the Union, would have been sufficient to have baffled many formidable transportations of troops from one state to another, which were then practiced. Our sea coasts, from their great extent, are more easily annoyed and more easily defended by a naval force than any other. With all the materials our country abounds; in skill our naval architects and navigators are equal to any, and commanders and seamen will not be wanting….

… Although it is very true that we ought not to involve ourselves in the political system of Europe, but to keep ourselves always distinct and separate from it if we can, yet to effect this separation, early, punctual, and continual information of the current chain of events and of the political projects in contemplation is no less necessary than if we were directly concerned in them. It is necessary, in order to the discovery of the efforts made to draw us into the vortex, in season to make preparations against them. However we may consider ourselves, the maritime and commercial powers of the world will consider the United States of America as forming a weight in that balance of power in Europe which never can be forgotten or neglected. It would not only be against our interest, but it would be doing wrong to half of Europe, at least, if we should voluntarily throw ourselves into either scale. It is a natural policy for a nation that studies to be neutral to consult with other nations engaged in the same studies and pursuits. At the same time that measures might be pursued with this view, our treaties with Prussia and Sweden, one of which is expired and the other near expiring, might be renewed….

It is impossible to conceal from ourselves or the world what has been before observed, that endeavors have been employed to foster and establish a division between the government and people of the United States. To investigate the causes which have encouraged this attempt is not necessary; but to repel, by decided and united councils, insinuations so derogatory to the honor and aggressions so dangerous to the Constitution, union, and even independence of the nation is an indispensable duty.

It must not be permitted to be doubted whether the people of the United States will support the government established by their voluntary consent and appointed by their free choice, or whether, by surrendering themselves to the direction of foreign and domestic factions, in opposition to their own government, they will forfeit the honorable station they have hitherto maintained.

For myself, having never been indifferent to what concerned the interests of my country, devoted the best part of my life to obtain and support its independence, and constantly witnessed the patriotism, fidelity, and perseverance of my fellow citizens on the most trying occasions, it is not for me to hesitate or abandon a cause in which my heart has been so long engaged.

Convinced that the conduct of the government has been just and impartial to foreign nations, that those internal regulations which have been established by law for the preservation of peace are in their nature proper, and that they have been fairly executed, nothing will ever be done by me to impair the national engagements, to innovate upon principles which have been so deliberately and uprightly established, or to surrender in any manner the rights of the government. To enable me to maintain this declaration I rely, under God, with entire confidence on the firm and enlightened support of the national legislature and upon the virtue and patriotism of my fellow citizens.

Annual Message to Congress (1797)

November 22, 1797

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.